“Economists and policymakers need to think more about inequality; we need to think about how everyone is doing,” said Sandra Black. “The timing is really right for this, and I’m very excited to be part of it.”

That excitement is fueled by a remarkable range of experiences. At UCLA, at the University of Texas, Austin, and now at Columbia University, the labor economist focuses her research on racial and gender discrimination, and on early-life influences on long-term outcomes. As a scholar at the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and San Francisco, she worked on bank deregulation and gender wage gaps, and on credit card risk for blue-collar workers.

A member of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute’s Advisory Board, she also served on the staff of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration, where her portfolio ranged from criminal justice to early childhood education to labor market monopsony, plus monthly labor market briefings for the president.

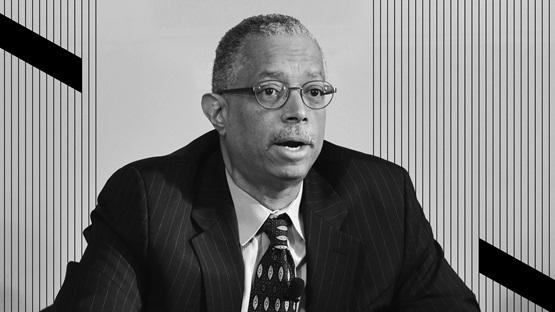

In the midst of the pandemic via Zoom from her New York apartment, Black answered questions from Managing Editor Douglas Clement.

The value of better schools

I’d like to ask about your 1999 paper about the value of schools. Among other things, you found that parents put a premium on education for their kids. That’s not a surprising result, of course, but it had been difficult to demonstrate statistically, and you managed to do so by looking at housing values on school district boundaries.

I was interested in education because my mom was a second-grade teacher in Los Angeles for many years. Originally, I wanted to identify the benefit to students of attending a better school. However, this is actually a very difficult question to answer, and lots of people are still working on it.

I approached it from a different perspective: Let’s look at how parents value living in a house that is associated with a better school. That’s an indirect value of the school—what the parents are willing to pay to have the right to send their children to a particular school. The problem is that when you buy a house, it has a whole bunch of different attributes. You’re buying the school that you get to send your kids to, but you’re also buying the neighborhood and the house itself and all the public amenities and all kinds of other things. And those things tend to be positively correlated. Better school districts tend to be in better neighborhoods with nicer houses—so isolating the part due just to schools is somewhat complicated.

But you disentangled the confounding variables by focusing on the boundaries.

What I did was look, in theory, at two houses sitting on opposite sides of the same street, where the attendance district boundary divides the street. The houses are clearly in the same neighborhood, they’re of similar quality, et cetera. The only difference between them is which elementary school the child from each home attends. And then you can ask, How different are the prices of those houses, and how does that difference relate to the differences in school quality?

What I found was that parents were willing to pay more for better schools, but much less than you would casually estimate if you didn’t take into account all these other factors. In Massachusetts, parents were willing to pay 2.5 percent more for a 5 percent increase in school test scores.

It was a really interesting project. I’d grown up on a street that actually separated the attendance district boundaries, so I knew these things mattered.

But in L.A., not in Boston where this research was focused.

Yes, in Los Angeles. And this was a long time ago, so pretty much all the information was hand-collected. The housing prices were in a database, but for the attendance district boundaries, I had to contact each school district to ask for their map. I would call them and say, “Can I get the map of your boundaries?” And they would ask, “What house are you thinking of buying?” I’d reply, “No, I actually just want the map.”

They’d usually send me a list of streets that were in the attendance district, and a friend of mine and I would sit down and try to create these maps. She was a very good friend.

Intergenerational wealth—nature versus nurture

In a recent paper in the Review of Economic Studies, you look at the correlation between parents and children in terms of wealth and other economic characteristics. You manage, again, to disentangle the impact of many confounding variables.

In a sense, you group them into nature versus nurture, and you find a powerful role for the latter in terms of intergenerational correlations in wealth—that environmental influences are more significant than biological factors.

Yes. We use Swedish data, which lets us link people across generations. So you can observe families and do a lot that is difficult to do in countries like the United States. This was work with Paul Devereux, Petter Lundborg, and Kaveh Majlesi. We were thinking about wealth inequality. That’s been a really big topic these days, especially with the work by Thomas Piketty and others.

One of the reasons rising inequality is so troubling is that there is so much persistence in wealth across generations. If everyone had the chance to be at the top, having a very unequal distribution of wealth might be less troubling. But the fact that there’s so much persistence across generations makes it much more worrisome.

We decided to look at what’s driving the correlations we see across generations in wealth using the Swedish data. Sweden collected data on wealth because they had a wealth tax. What’s unique to the Swedish data is that we can observe adopted children and, importantly, we can observe both their biological and their adopted parents. So when you observe a child’s wealth as an adult, you can see how correlated it is to their adopted parents’ wealth and to their biological parents’ wealth. Other researchers have done this to look at things like education and income persistence. We thought it was important to look at wealth.

And, as you said, when we do that, we find that environment, or the adoptive parent, matters a lot, and more than the biological parent, unlike outcomes such as education or even income, which had more of a biological component. This is really important because it says people aren’t wealthy because there’s something inherently different about them that makes them better able to accumulate wealth; they’re wealthy because they have these opportunities.

And adopted children “moved to better opportunities” by joining a wealthier family.

Exactly. It’s about the opportunities you have growing up that make you wealthy in the long run. It’s really important in today’s society to think about that because the wealthy have disproportionate influence in our society. There are simply a lot of advantages to being wealthy, and the idea that it’s some sort of innate skill or ability that got you there simply isn’t valid. A lot of it is simply the opportunities your parents were able to provide you with. The unfairness of that seems really important.

It’s interesting, too, to note that depending on the outcome you measure, you find that environment has a very different role. Education, for example, has a big biological component, as you might expect—underlying ability might matter more for education. The fact that wealth really is so disproportionately due to environment, I think, is really important.

Birth order and leadership

You’ve looked at the impact of birth order on a number of characteristics: IQ, adult health, and other physical and cognitive traits. But you’ve also studied noncognitive outcomes in relation to birth order, things like leadership ability.

Would you tell us about that paper?

Birth order is a great topic to study. People are inherently interested in it because everyone has a birth order.

May I ask yours?

I am the first-born, which conveniently happens to be best for many outcomes. [Laughs]

You mention that in your papers, of course.

As my disclaimer? Conflict of interest? Yes, of course. [Laughs]

From a policy perspective, of course, it doesn’t have direct policy implications. You can’t decide to have three first-born children in the same family because you find out that first-borns do better. But it does provide insight into what determines individual outcomes and helps inform how kids become the adults that they are.

Noncognitive skills are interesting because of the various psychological theories about birth order and children’s personalities. But it’s very hard to study this systematically for two reasons. First, because birth order is correlated with family size. Every family will have a first-born, but only big families have a fifth-born. So family size itself may have an effect on a person’s outcomes. In addition, it’s not random which families are bigger. Less-educated and poorer parents tend to have more children.

All these things are confounding factors when you try to isolate the effect of birth order, so you need a big data set to do the analysis. And it’s even harder because you need data on personality, which is difficult to measure and is generally not collected on a large scale.

This is co-authored work with Björn Öckert and Erik Grönqvist, and what we do is use the measures of noncognitive skills that were collected in Swedish military data. Military service was mandatory, and when people enlisted in the military, they were given an IQ test, which is why we observe IQ for many people in Scandinavian countries. But they were also assessed by psychologists in terms of suitability for leadership positions and other noncognitive skills.

We used that measure to try to get at personality, and what we find is that, again, it is better to be the first-born in the family. They’re more likely to be in positions requiring leadership ability—managers and the top managers in the company. They are also more emotionally stable and willing to assume responsibility than later-born children. And we find that it’s systematically declining with the birth order.

We also have a cool finding about the composition of your siblings. If you’re later-born and you have older brothers, we find much larger negative effects than when you have older sisters. You are also more likely to be in a creative occupation. If you have sisters, you’re not. There are some real, systematic patterns in personality that don’t necessarily coincide with all the theories from psychologists.

The collision of those research worlds—psychology and economics—is relatively recent, I suppose, with the advent of behavioral economics.

True. Economics has really expanded a lot in the last [few decades]. What constitutes labor economics, which is what I do, seems to have gotten a lot broader.

An interesting thing about this is that we never find biological explanations for the birth-order effects that we find. When we try to look at mechanisms driving the birth-order effects, biology, in fact, seems to work in the other direction—later-born children tend to be heavier at birth, which is associated with positive longer-run outcomes. We compare social birth order in contrast to biological birth order too. So if one of your older siblings died or was given up for adoption, your social birth order would be different from your biological. We find that all these effects are related to your social birth order, not your biological birth order. That too is interesting.

You find some amazing ways to slice data.

I know, isn’t it cool? It’s like a puzzle. You want to figure something out, and it’s like, How can I tease out that puzzle from the data? We’re lucky to have the data and the tools.

Gaining, and losing, admission to top colleges

In recent research, you look at outcomes for students who gained and lost access to the most selective colleges in Texas after the state adopted its Top Ten Percent (TTP) plan. You uncover something rarely seen in economics, gains in both equity and efficiency. What were your findings?

I think that’s a really interesting study. I got involved in this in part because I was at the University of Texas, Austin, until recently, and we were able to get access to Texas education data. The Top Ten Percent plan was passed in 1997 in response to a court ruling that affirmative action in college admissions was no longer legal. To maintain diversity, Texas implemented this plan. The idea is that the top 10 percent of every high school in Texas would be automatically admitted to any University of Texas institution—any one of their choice.

All of a sudden, disadvantaged high schools that originally sent very few students to selective universities like the University of Texas, Austin—the state’s top public university— found that their top students were now automatically admitted to UT Austin. If they wanted to go, all the student had to do was apply. There was also outreach, to make students aware of the new admissions policy. The hope was that it would maintain racial diversity because the disadvantaged high schools were disproportionately minority.

It’s not obvious that the goal of maintaining diversity was realized, in part because even though a school may have a disproportionate number of minority students, its top 10 percent academically is often less racially diverse than the rest of the school. There is some debate about whether it maintained racial diversity.

What you do see, however, is that more students from these disadvantaged schools started to attend UT Austin. And students from the more advantaged high schools who were right below their school’s top 10 percent were now less likely to attend. So there’s substitution—for every student gaining admission, another loses. I think that is true in every admissions policy, but we don’t always consciously weigh these trade-offs.

It’s zero sum, essentially?

Yes. Here, we’re trying to explicitly think about, and measure, these trade-offs. In this paper, joint with Jesse Rothstein and Jeff Denning, we show that the students who attend UT Austin as a result of the TTP plan—who wouldn’t have attended UT Austin prior to the TTP plan—do better on a whole range of outcomes. They’re more likely to get a college degree. They earn higher salaries later on. It has a positive impact on them.

But what was really interesting is that the students who are pushed out—that’s how we referred to them—didn’t really suffer as a result of the policy. These students would probably have attended UT Austin before the TTP plan. But now, because they were not in the top 10 percent [of their traditional “feeder” school], they got pushed out of the top Texas schools like UT Austin. We see that those students attend a slightly less prestigious college, in the sense that they’re not going to UT Austin, the flagship university. But they’ll go to another four-year college, and they’re really not hurt. They’re still graduating, and they’re getting similar earnings after college.

So the students who weren’t attending college before [because they didn’t attend a traditional feeder school] now are, and they’re benefiting from that in terms of graduation rates and income, while the ones who lose out by not going to Texas’ top university aren’t really hurt that much. It seems like a win-win.

It strikes me that here again you're dealing with kids on the margin.

Economists are always thinking about the margins!

Council of Economic Advisers

You worked for about a year and a half on the Council of Economic Advisers. What issues did you work on? And which role do you prefer: being an adviser or a scholar?

In 2015, I was asked to be a member of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. It was not something I thought I would ever do, but it was such a great opportunity that I couldn’t say no. I got to work on a lot of really important issues. A great thing about working for the government—particularly in that capacity—is you feel like what you do every day really matters; whereas, in academia, a lot of our time is spent investing in long-run projects. In D.C., it felt like whatever we were talking about today could be happening tomorrow, so it felt really relevant and important.

My portfolio was labor economics broadly defined. One of my responsibilities was briefing the president on the jobs and unemployment numbers that come out once a month—I would go with Jason Furman, the chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, to brief President Obama before the numbers came out on the first Friday of each month.

I was particularly interested in early childhood education, something that I had done research on prior to coming to CEA, and the CEA did a number of reports on that while I was there. But topics like retirement behavior that I had not previously studied were also part of my portfolio.

We also got involved in the criminal justice portfolio while at the White House; there’s been a lot of important new research on the economics of crime that I think was really useful to the policy folks in the White House.

One issue that we worked on while I was there that I was really excited about is monopsony in labor markets. While most standard models start from a place of perfect competition—that individual firms take the wage they have to pay as set, and they can get as many workers as they want at that wage. In a perfectly competitive labor market, workers are going to move if the job next door pays one cent more an hour.

But we know this isn’t really how the labor market works. There are lots of reasons workers don’t leave. Firms have power over workers and can set their wage.

Still, because there aren’t many company towns these days, we don’t tend to think about monopsony for labor markets.

Right. Originally, economists thought of a company town where there were no other job opportunities, so the firm had lots of power. That is the extreme case. We are likely in some intermediate space.

And now people are paying a lot more attention to the idea that firms can—and do—take advantage of workers. You see lots of discussion these days—particularly in the current environment—about workers getting paid very low wages and not getting paid sick leave. But, for a variety of reasons, these workers can’t easily move to a better job. The idea of firms exercising power over workers has made a real revival in the economics literature recently.

Your second question—which job do I prefer: adviser or academic? That’s easy to answer: being a professor.

I like thinking about things for long periods of time, and it was quite the opposite when I was in D.C. There, I was scheduled every 15 minutes. Each meeting would cover a different topic, and I had to be ready to be an expert on A, then an expert on B, and then an expert on C.

It is the antithesis of being an academic, and it’s a skill that I think a lot of academics don’t naturally have, me included. It was a really hard transition from academia to the policy world. Coming back to academia was hard too. I noticed that my attention span had become so much shorter. It took six months, at least, before I could sit and read a whole paper and just think about that paper. Being at the CEA was a very different experience. I really enjoyed it, but I was happy to come back to academia.

The Institute

You recently joined the Institute as an advisor. What do you see as the Institute’s role in efforts to provide greater opportunities and more economic inclusion?

I really like what the Institute is doing. I met Abbie Wozniak years ago and, like me, she also worked at the Council of Economic Advisers. I was so excited when I found out she was moving from Notre Dame to lead this group.

People are becoming much more open to this idea of inclusive growth—the idea that GDP is not a sufficient statistic for how our society is doing. People—and, by that, I mean economists and policymakers—need to think more about inequality; we need to think about how everyone is doing.

The timing is really right for this. The movement needs some leadership, and it’s a hard thing for academics to do because we are so isolated. I think it’s important to have this type of organization where people who are all interested in the same issue can present their ideas and know that there is an audience for it. I was really excited to be part of it. And I think the reaction to it has been really outstanding. It’s been very well-received by scholars and policy people.

The pandemic

How is the pandemic shaping your research? And what impact do you see it having on economics as a profession?

For me personally, being in New York City, it reinforces my concerns about our society. In many ways, it highlights the importance of the Institute’s work. We need to pay more attention to understanding how our society is failing so many of its members. To me, the pandemic has heightened all my fears about unfairness and inequality in our society.

We see the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on low-skilled workers. We call them essential workers, but we don’t offer them sick days, and there are very few protections for many of them.

The fact that many of them don’t have health insurance reinforces the importance of making sure that everyone has health care—not simply access, but actual health care. It makes sense from a cost perspective, but also from an equity perspective. It’s part of what makes a functioning and equitable society.

The pandemic has been really hard to watch, but I’m very aware that I’m lucky because I’m watching it more than I am experiencing it. I’m grateful for that, but watching how things are unfolding is so disheartening. It makes me all the more committed to doing good research and thinking about how research can effect change in society.

How do you think it will change the profession?

I’m not in a hopeful mood right now. I have a very hard time following the news these days. I just find it so upsetting. I don’t know how, as a society, we are letting these things happen. And I feel powerless.

I guess I hope that it will change the profession in that people become more aware of how costly bad policy can be

That would be my hope, that we will learn.