Families and businesses agree that inadequate child care, both in terms of availability and reliability, is a challenge for Montana. Many Montana families need child care: At least 73 percent of Montana’s more than 25,000 households with children ages zero to five years have all parents in the workforce and require child care. In January through April 2020, two surveys of Montana households and businesses, respectively, gathered information about the impact of child care availability and reliability on family finances, business hiring, and economic activity in Montana. Over half of parents reported that finding affordable child care is a challenge, while over half of employers reported a shortage of affordable child care options in their community.

Most households and employers, surveyed respectively by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana (Missoula) and the Montana Department of Labor & Industry, responded to the surveys prior to the major disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. (See the “Child care survey methodologies” sidebar below for more on the surveys themselves.) As the economy reopens, parents with young children are returning to their jobs, driving up demand for child care. Insights from these surveys can inform families, businesses, and policymakers about the important role child care plays in facilitating the economic recovery and sustaining the economy.

Economic consequences of inadequate child care

Results of the household survey show that 72 percent of parents use at least one non-parental child care arrangement. (See Table 1.) A number of these settings, such as licensed child care centers or home-based family or group care providers, require tuition payments. Families also often pay for child care if they turn to another family member, a babysitter or nanny, or an unlicensed provider who cares for a few children.

| Type of child care arrangement | Share of households |

|---|---|

| At least one non-parental child care arrangement | 72% |

| Pre-K or kindergarten | 25% |

| Other family member | 24% |

| Licensed child care center | 23% |

| Licensed home-based family or group care provider | 11% |

| Early Head Start or Head Start | 9% |

| Unrelated person who cares for a few children | 6% |

| At home with babysitter or nanny | 3% |

Since families with young children are typically in the early earning years of their careers, child care prices are often relatively challenging for them to pay. Many are bringing home less income than they will in their later years while facing costs associated with family formation, such as to rent or buy a larger living space or purchase a vehicle that fits their needs. Averaged across households that pay for child care, annual expenses reach $7,900, or about 14 percent of median income for Montana households with children ages zero to five years. Households that use center-based infant care—the most expensive age and care option—paid on average $12,750. Families with income of 150 percent of the federal poverty guideline ($39,300 for a family of four) or lower may qualify for a state subsidy to help pay for care.

Survey results show that 78 percent of respondents experienced at least one challenge in accessing child care. Among those respondents, 57 percent reported that finding affordable child care is a challenge. Other top challenges include finding back-up care, emergency care, or care for a sick child; and finding high-quality care. (See Figure 1.)

The challenges of accessing reliable child care and the conditions of chosen arrangements can disrupt parental employment. When parents can’t find affordable child care that fits their family’s schedule and needs, they may choose to work fewer hours or not work at all. And if child care arrangements prove unreliable, parents may end up leaving work early, missing full work days, or being distracted and less productive on the job.

Respondents noted a number of child care-related work problems that affected their employment, work hours, and income during the past year. Some child care-related work problems can directly affect household income in the near term, such as missing work (62 percent), changing from full-time to part-time work (15 percent) or quitting a job (12 percent). (See Figure 2). Other child care-related work problems, such as declining to pursue further education or training (26 percent) or turning down a job offer (22 percent), can affect a parent’s career trajectory.

All of these challenges due to inadequate child care add up to substantial costs to Montana’s households and overall economy.1 (See Table 2.) Montana parents with young children lose $5,700 per household annually due to missing work, switching from full-time work to part-time work, or turning down a job offer because of inadequate child care. Notably, the household survey doesn’t necessarily capture costs associated with parents leaving the labor force permanently, which are potentially much larger. But other costs are also substantial: Two-parent households where both parents work lose an annual average of $7,440 in wages; single-parent households lose an average of $3,500.

Even households with one parent at home rely on child care for when the stay-at-home parent needs coverage for appointments or other activities. Two-parent households in which one parent works and one parent stays at home lose an annual average of $2,960 due to child care problems. Collectively, Montana parents of young children lose more than $145 million in wages because of inadequate child care. In addition, the federal government and Montana’s state government accrue $32 million less annually in income tax receipts due to lost parental wages from inadequate child care.2

Inadequate child care also affects Montana businesses through revenue losses due to lower employee productivity, such as missing work or declining to pursue further job training or education, as well as higher turnover rates and related employee-recruitment costs. Similarly, a lack of child care can shrink the pool of available qualified workers. Altogether, Montana businesses lose close to $55 million annually due to child care problems.

| Loss to households with children ages zero to five years | Loss to businesses | Loss to taxpayers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average per household with children ages zero to five years | $5,700 | $2,150 | $1,260 |

| State total | $145.1 million | $54.6 million | $32.0 million |

Disproportionate impacts on low-income and American Indian households

More low-income and American Indian households report child care-related work problems compared with high-income and White households, respectively. While inadequate child care affects a broad range of Montanans, low-income and American Indian households carry the heaviest burden. Addressing inadequate child care for these families in particular could help boost near-term employment levels and long-run career prospects.

On average, households earning $30,000 or less lose about $3,400 in wages annually—more than 10 percent of their income—due to issues related to inadequate child care. Parents in low-income households were more likely than parents in high-income households3 to:

- decline to pursue further education or training in connection with their employment (38 percent versus 21 percent);

- turn down job offers (36 percent versus 12 percent);

- change from full-time to part-time work (24 percent versus 10 percent) or

- quit their jobs (26 percent versus 5 percent).

The household survey shows similar findings in comparing American Indians, the second-largest racial group in the state, with Whites. American Indian respondents were more likely than White respondents to:

- decline to pursue further education or training in connection with their employment (47 percent versus 24 percent);

- turn down job offers at a higher rate (37 percent versus 22 percent); or

- quit their jobs (27 percent versus 10 percent).

A comparison of urban and rural household responses did not show substantial differences in the impact of inadequate child care on employment and income. However, 60 percent of urban households report difficulty finding affordable child care, compared with 49 percent of rural households.

Businesses recognize child care shortages

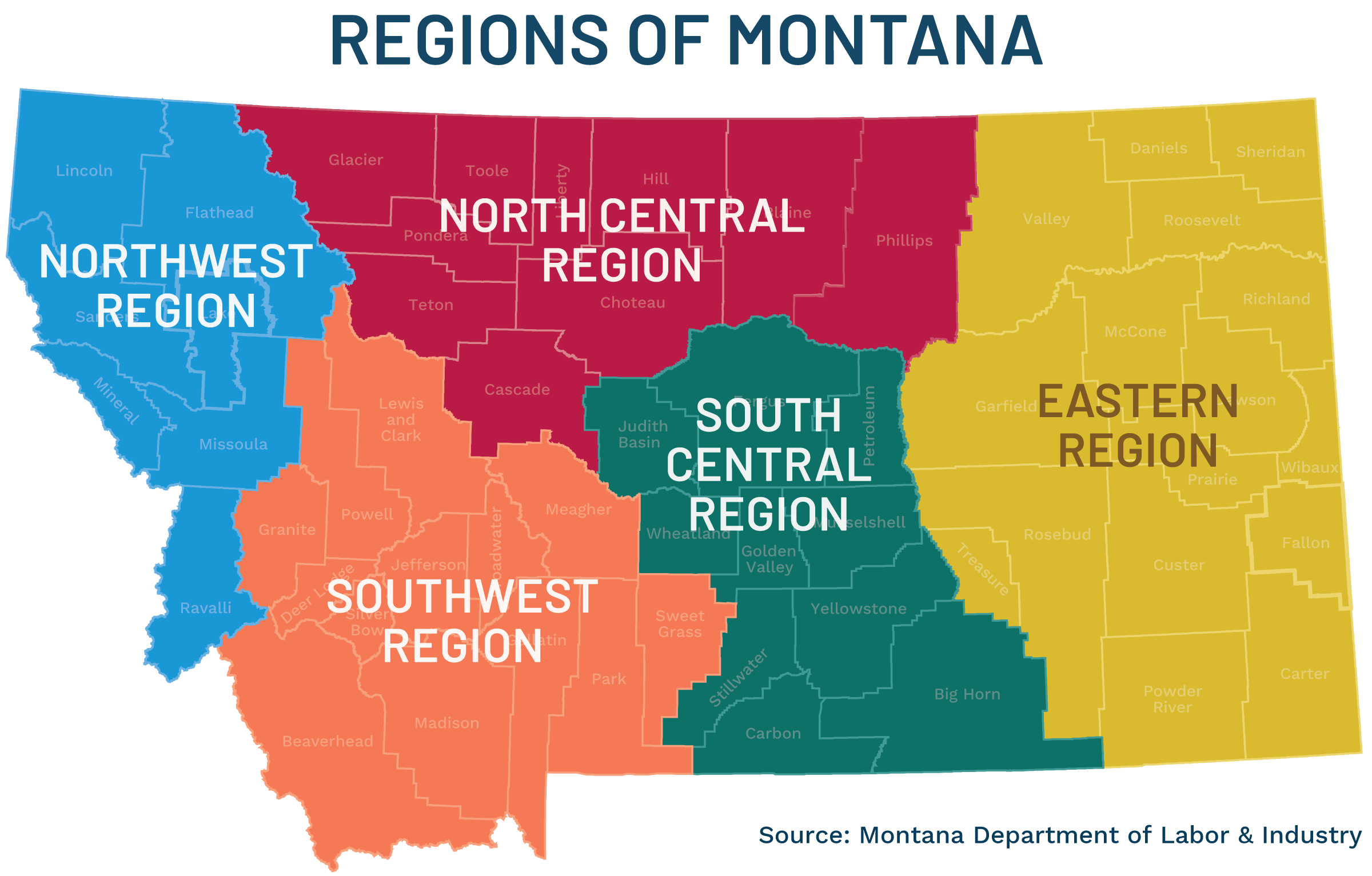

According to the business survey, over half of Montana businesses, 56 percent, indicated there is a shortage of affordable child care options in their community, and 61 percent noted that increasing access to child care should be a priority. By region, respondents in the Southwest region, which includes Bozeman, Butte, and Helena, and those in the more rural Eastern region of the state were more likely to indicate there is a shortage of child care in their community than respondents from other parts of the state. (See the map of regions in Montana.)

About 40 percent of Montana businesses indicated that inadequate child care affects their company’s ability to recruit or retain qualified workers. This response is relatively consistent across geographic regions but varies by industry. (See Figure 3). For example, the industry groups that comprise Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate, Information, Utilities and Education, Health Care, Professional and Technical Services, Government are more likely to report that inadequate child care affects employee retention. Meanwhile, Agriculture, Construction, Mining and Manufacturing, Wholesale Trade, Transportation—sectors that employ relatively fewer women—are less likely to consider inadequate child care as affecting employee retention.

In response to child care and other employee needs, 75 percent of Montana businesses offer flexible work arrangements to some or all of their employees. Among respondents to the household survey who work for a Montana employer, 28 percent indicate that their employer offers flexibility and is tolerant of child care needs. Fewer businesses offer benefits specific to child care. For example, 16 percent provide dependent care assistance plans or dependent care flexible saving accounts that employees and employers can contribute to. These benefits reimburse employees’ child care expenses under certain conditions. About 6 percent of Montana businesses that offer dependent care assistance plans to their employees make contributions to them.4

Other types of child care benefits are offered less frequently, such as onsite child care (5 percent), information on local child care options (4 percent), back-up or emergency child care services (1 percent), or subsidized child care expenses (less than 1 percent). These results mirror findings from the household survey, where only a few respondents indicated that their employer offers these types of child care benefits. Similar to the responses about how inadequate child care affects worker retention, the industry groups that comprise Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate, Information, Utilities and Education, Health Care, Professional and Technical Services, Government are more likely to provide child care benefits than other industries.

Lessons learned for the pandemic and beyond

The household and employer surveys’ results suggest that the child care sector plays an important role in the economy whether in an expansion or a downturn. During the outset of the COVID-19 crisis, policymakers recognized that without child care, many essential workers with young children couldn’t get to their jobs. The increased attention child care has received during the pandemic has helped many business leaders and policymakers recognize the importance of child care as a vital component of workforce infrastructure.

As the economy continues to recover—and once the pandemic abates—child care markets will likely look more like they did during early 2020 when households and employers responded to the surveys. The findings suggest that supporting child care access can have a positive economic impact on Montana’s households, businesses, and taxpayers. They also show that low-income and American Indian families stand to benefit the most from targeted interventions that increase access to affordable and reliable child care. Addressing inadequate child care for these families in particular could help boost near-term employment levels and long-run career prospects. Supporting child care is not just in the best interest of families with young children. Businesses, taxpayers, and the Montana economy benefit as well.

Endnotes

1 In the household survey, parents report the occupation and industry in which they are employed and how many hours of work and related earnings they lost due to child care problems. These data are used to estimate economic costs.

2 This study focuses on parental employment and doesn’t include potential long-run benefits to children. Research by the Minneapolis Fed shows that high-quality early care and education programs can improve children’s school success, which reduces societal costs and increases earnings and tax revenue, particularly when reaching disadvantaged children.

3 Low-income refers to the lowest third of household incomes and high-income refers to the highest third of household incomes.

4 The Internal Revenue Service limits an employee’s pre-tax contribution to $5,000.