Every year, taxation by state and municipal governments siphons tens of millions of dollars away from Indian Country and toward non-tribal communities. The outflow of tax dollars hinders tribal governments’ ability to serve their constituents, and it forces tribal leaders to face a difficult question: Should tribes add their own layer of taxation to make up for the lost revenue? In considering the question, tribes must take history, sovereignty, risk, self-determination, and other factors into account. Ultimately, a tribe’s decision to tax hinges on the needs of its constituents, its relationships with other governments, and its capacity to deliver public goods to its community.

Taxation supports public goods

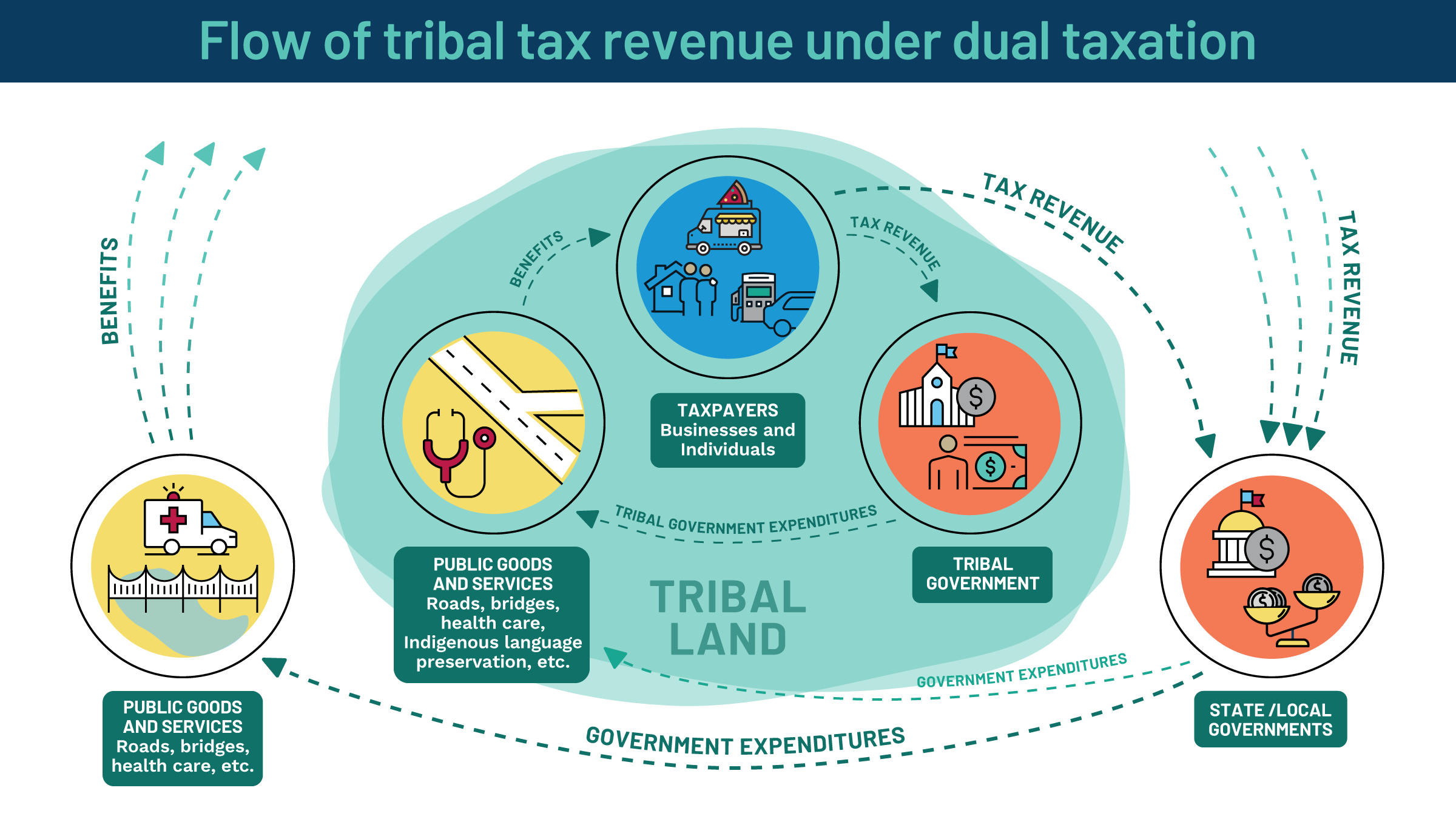

In a common flow of tax dollars, individuals and businesses pay taxes—including property taxes, income taxes, and sales taxes—to the government, which uses the resultant revenue to fund public expenditures, such as education, roads and bridges, and health care. Tribal governments fund the same types of public goods, as well as tribal-specific activities, such as language preservation, cultural programs, and elder assistance.

Governments with overlapping jurisdictions have collaborated for centuries to establish fair strategies and processes for tax collection and apportionment. However, even as tribal governments conduct economic development and provide public goods to their Indian and non-Indian constituents, tribal nations have not been accorded the same regard that states routinely provide to other states. As described in a 2016 paper by Indian Country experts, states often tax economic activity in tribal nations that they would not attempt to tax in a neighboring state.

Tribal governments have never ceded their taxation authority through treaties or other means. Despite their right to tax, only in the past several decades have tribal governments expanded the exercise of this sovereign power. (To our knowledge, no one has the complete picture of how many tribal governments levy taxes.) In doing so, they have met considerable pushback, litigation, and unfavorable court decisions. For example, while upholding tribes’ sovereign authority to tax, the U.S. Supreme Court in several key decisions has substantially increased the opportunity for states to levy taxes in Indian Country. As a result, the prospect of dual taxation limits the ability of tribes to raise revenue and make needed investments, creating an unattractive market for investment and business development, depressing regional economies, and infringing on tribal sovereignty.

What is dual taxation?

Dual taxation occurs when more than one government levies taxes on the same transaction or holding. For example, a taxpayer purchasing a tank of gasoline on tribal lands may pay gas taxes to both a state government and a tribal government on that single transaction. This taxation regime tends to advantage the government that levies a tax first, because any other government’s subsequent decision to tax would discourage economic activity. For Indian Country, then, even as tribes are the original governments on their lands, their relatively recent exercise of their sovereign tax authority diminishes the potential value of taxation as a tool for generating reliable revenues.

As state governments levy taxes on additional goods, services, and holdings in Indian Country, tribal governments are in a bind. On the one hand, adding taxes on top of those claimed by state or local governments may discourage sales, investment, and development in tribal communities. On the other hand, forgoing taxation requires alternative, consistent sources of revenue. And often these alternatives necessitate affordable capital themselves, which is elusive in Indian Country. Either way, tribal communities and citizens lose out.

While non-tribal governments can and do fund public goods and services on tribal lands, it is unclear how much of the tax revenue collected on tribal lands returns to tribal communities. Moreover, even if non-tribal governments reinvested all of the tax revenue collected on tribal lands into tribal communities, those funds may not reflect the tribal community’s top priorities. For example, the state may invest heavily in transportation infrastructure (roads, bridges, etc.) while the tribal community prefers to fund tribal-specific infrastructure, such as Indigenous language preservation. The dual-taxation bind thus not only constrains revenue but also jeopardizes tribal self-determination.

What’s good for Indian Country is good for all

When tribal economies thrive, state economies and labor markets flourish. Conversely, when the economic potential of Indian Country languishes, large swaths of state economies stagnate. Dual taxation, one of many barriers to tribal economic prosperity, constrains economic growth by either increasing the cost of doing business in Indian Country or limiting the revenue options that tribal governments can use to fund public goods and services.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Policy solutions to the challenges of dual taxation in Indian Country are in sight, and upcoming Center for Indian Country Development articles and papers will outline these in more detail. Concerted, collaborative effort by federal, state, and tribal stakeholders can result in taxation regimes that not only allocate revenue more equitably but also create an attractive environment for business investment and development. And when Indian Country prospers, we all benefit.

Casey Lozar is a Minneapolis Fed vice president and director of our Center for Indian Country Development (CICD), a research and policy institute that works to advance the economic self-determination and prosperity of Native nations and Indigenous communities. Casey is an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and he’s based at our Helena, Mont., Branch.