The rise of despair—profound psychological distress and poor mental health—among White Americans since the 2000s has been the focus of a substantial amount of research and media coverage. In fact, it is often claimed that the rise of despair among less-educated White Americans is generally at higher levels than among people of color, and that “this despair reflects the decline of the white working class.” However, this conversation omits a critical group of Americans: the nation’s nearly ten million Native American people. Our recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper finds that levels of consistently poor mental health, or chronic distress, among Native peoples were greater in every year from 1993 to 2020 than among White Americans and other groups. Moreover, these levels of distress are rising.

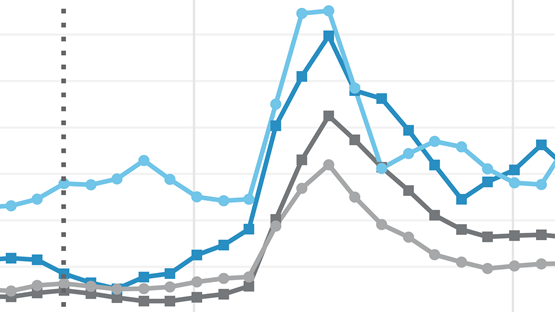

Nearly 10 percent of Native American respondents said that every day of the last month was a bad day for mental health in 2019. By contrast, only about 5 percent of White Americans reported the same degree of distress. The significant difference even exists among only those without a college degree. In Gallup surveys as well, Native Americans report experiencing greater feelings of pain and worry than other population groups.

Much of this difference in chronic distress is arguably related to economic factors: Native Americans and White Americans with similar economic circumstances had rates of distress that were statistically indistinguishable. While these findings cannot definitively establish whether poor economic conditions cause greater distress among Native Americans, they suggest that increasing the economic opportunities available to Native peoples could be key to reducing the prevalence of chronic distress. Alternatively, policies that diminish chronic distress may also increase economic opportunity; for instance, chronic distress could make it more challenging for Native people to attend and complete college.

Despite the distressing rates of chronic distress among Native peoples, our findings also provide potential reasons for optimism. The difference in chronic distress between Native Americans and White Americans is much smaller for those under 30 years of age. Further research is necessary to determine whether this is due to differences emerging later in life or to young Native peoples having greater opportunities and access to resources than past generations. In addition, the states with the largest Native American populations—Alaska, Arizona, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Oklahoma—have lower rates of Native American chronic distress. One possible explanation is that having a community of other Native peoples may foster greater resilience against chronic distress. Clearly, these racial disparities in chronic distress are not inevitable.