What would happen to labor markets if child care didn’t exist? What would the work force look like if schools didn’t watch over children Monday through Friday?

We now know.

As COVID-19 forced the closure of day care facilities and schools across the nation, parents became full-time caregivers. And the impact on their work lives was enormous.

Exactly how this played out, and especially how it affected gender balance in labor markets, is the focus of new research by Misty Heggeness, a U.S. Census Bureau economist and former visiting scholar at the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute.

By comparing employment patterns in states that closed early with those in states that closed later, she analyzes how parents’ labor supply shifted in response to the COVID-19 shock. Did they leave their jobs altogether, take temporary leave, or devise other mechanisms to cope with increased child care responsibilities? Did the closings affect mothers and fathers differently?

In terms of reported workforce attachment and unemployment, Heggeness finds no immediately measurable impact. In the very short term, parents didn’t leave the labor force entirely and they weren’t fired. But the workforce definitely changed. Many parents took leave from their jobs. Not fathers though; just mothers with schoolage children. Fathers, for their part, cut back slightly on working hours.

While stressing that these are shortterm results and that labor markets will no doubt adjust over time, Heggeness speaks emphatically about both short- and longrun impacts these immediate changes are likely to have.

Balancing work with increased household responsibilities, she points out, may increase stress, reduce sleep and leisure, and potentially harm job productivity. In the long term, it may also impair job prospects for both mothers and fathers.

Her findings indicate that mothers have borne the greater burden compared with both fathers and other women, and she concludes that “a gender-equal labor market will never be fully realized unless we acknowledge the double bind of mothers and [their] dual responsibilities.”

Detailed model, deep data

Heggeness starts with a standard household model but incorporates the realities of parental bargaining over resources, including time, and inequality between spouses. Beyond that, her model incorporates pandemic reality: school closures, business shutdowns, stay-at-home ordinances.

In normal times, parents may pay for child care if it’s less expensive than what the parent can earn at his or her job. In pandemic times, that’s not an option. Time spent in unpaid child care ramps up to 24/7—meaning less paid labor and less leisure. “Juggling it all,” she writes.

Her data set, drawn from monthly panel data from the Current Population Survey, covers the first five months of both 2019 and 2020 and follows the same individuals over time. The final sample is devoted to parents of schoolage children, including about 176,000 observations from nearly 63,000 parents.

Moms (not dads) took leave

To focus on the COVID-19 shock’s impact on labor patterns, Heggeness compares workers in 18 states that closed schools early, defined as on or before the week including March 12, with those closing the following week or later (33 states). She looks at six variables to gauge labor force attachment, and amount and value of labor provided.

Heggeness’ empirical analysis measures the change in weekly earnings and other labor variables that is due exclusively to closure of child care centers and schools, isolated statistically from simultaneous changes occurring in all states and pre-existing differences among them.

The results are unambiguous. In the very short term, the COVID-19 shock had no impact on employment or attachment to labor force. Nonetheless, parents with jobs had to make serious adjustments to cope with school and child care closures.

First and foremost, many mothers took immediate leave from their jobs. “Mothers with jobs in early closure states were 68.8 percent more likely than mothers in late closure states to have a job but not be working,” Heggeness finds. There was no such difference for fathers, nor for women without school-age children.

How did fathers adjust? They worked a bit less, reducing weekly hours by about 1.3 percent (about half an hour per 40-hour work week), compared with fathers in late closure states. Unlike mothers, however, they didn’t take work leave.

Surprisingly, household earnings didn’t decline, suggesting that mothers took paid leave, and fathers who worked shorter hours were salaried or able to work remotely.

Implications for parents’ careers

What does this mean for employees, for companies, for the economy in general? And what does it signify for families— mothers especially?

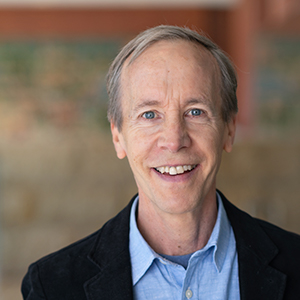

STUDY AUTHOR

MISTY HEGGENESS, Principal Economist/Senior Advisor, U.S. Census Bureau

It’s clear that school and child care closures affect mothers more than other women, and mothers more than fathers, reflecting gender imbalance within households in both bargaining power and child-rearing roles. Social norms and expectations also play a role, observes Heggeness. “It is more socially acceptable for mothers in the workplace to take leave for family obligations, but less so for fathers.”

For both parents, balancing additional household responsibilities with work can create short-term problems: increasing stress, reducing sleep and leisure time, and impairing productivity on the job.

The long-term implications are also worrisome, leaving both parents “vulnerable to career scarring,” she writes. “When mothers must take leave for childcare purposes … it has detrimental effects on opportunities for career advancement. … When fathers’ hours are reduced, it leaves them [similarly] vulnerable.”

But while both parents adjust work hours, Heggeness notes that taking leave from work is more drastic than working a bit less, indicating that the work-home time constraint is more binding for mothers. “The dual responsibilities of household production and formal labor market activities … are disproportionately distributed toward women, particularly mothers,” she writes. “We need to prioritize discussions of child care.”