Plan Contents

- Section 1: Summary of the Minneapolis Plan to End Too Big To Fail

- Section 2: Recommendations: Key Support and Motivation

- Section 3: General Empirical Approach for the Capital and Leverage Tax Recommendations

- Section 4. Technical Calculations for the Capital and Leverage Tax Recommendations

- Section 5: The Banking and Financial System Post-Proposal Implementation

- Appendix A: The Leverage Ratio in the Minneapolis Plan

- Appendix B: Ending TBTF Initiative Process

We propose to end TBTF through four steps.

In Step 1, we propose significantly increasing the minimum capital requirements for covered banks. The equity capital requirement would be 23.5 percent of risk-weighted assets. New covered banks that come into existence due to mergers, acquisitions, or the formation of a new holding company will be subject to the requirements upon completion of the corporate action. The Minneapolis Plan will index the $250 billion in assets threshold that defines covered banks to nominal GDP so that it continues to target relatively large banks in the future. Covered banks will have five years post-Plan implementation before they must comply with this requirement.

In Step 2, the Minneapolis Plan will force these banks to either cease being systemically important—as judged by the Treasury Secretary—or face the SRC, bringing their total equity capital up to a maximum of 38 percent over time. This process will also start five years after enactment of the proposal.

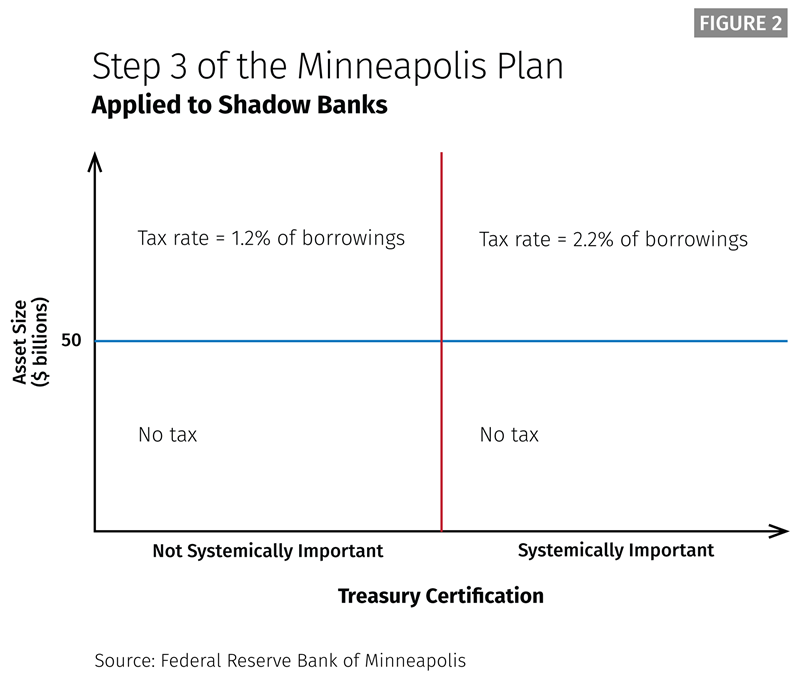

In Step 3, the Minneapolis Plan will impose a tax on the borrowings of shadow banks7 with assets over $50 billion. Shadow banks that are not systemically important will face a tax rate of 1.2 percent of borrowings outstanding. The shadow banks that remain systemically important will face a tax rate of 2.2 percent. The Plan will also index the $50 billion threshold to nominal GDP. This aspect of the Plan will go into effect five years after enactment.

Finally, in Step 4, we propose creating a much simpler and less-burdensome supervisory and regulatory regime for community banks. This recommendation reflects the ultimate goal of our Ending TBTF initiative: to create a safe and sound banking system serving firms and households with effective and appropriately sized regulation and supervision.

In Section 2.1, we provide more details on our proposal.8 In Section 2.2, we define the nature of the TBTF problem more precisely and explain why this problem remains so important even after the U.S. government has enacted reforms to try to address it. Section 2.3 explains the similarities and differences between our proposal and other potential transformative options to end TBTF. Finally, in Section 2.4, we discuss what our proposal means for other banking supervision and regulation policies, particularly with regard to community banks, but also with regard to current reforms aimed at ending TBTF. Key specifics and methodologies used in this section are spelled out in Sections 3 and 4.

The material in this section and throughout the proposal reflects the product of a two-year effort that included a broad public review of a wide variety of ideas to end TBTF. Appendix B discusses this process and summarizes lessons learned and key points made over the course of our Ending TBTF initiative.

2.1 The Minneapolis Plan to End TBTF

In this section, we summarize the key features of each aspect of our Plan. We first offer two ways of understanding the totality of the Plan.

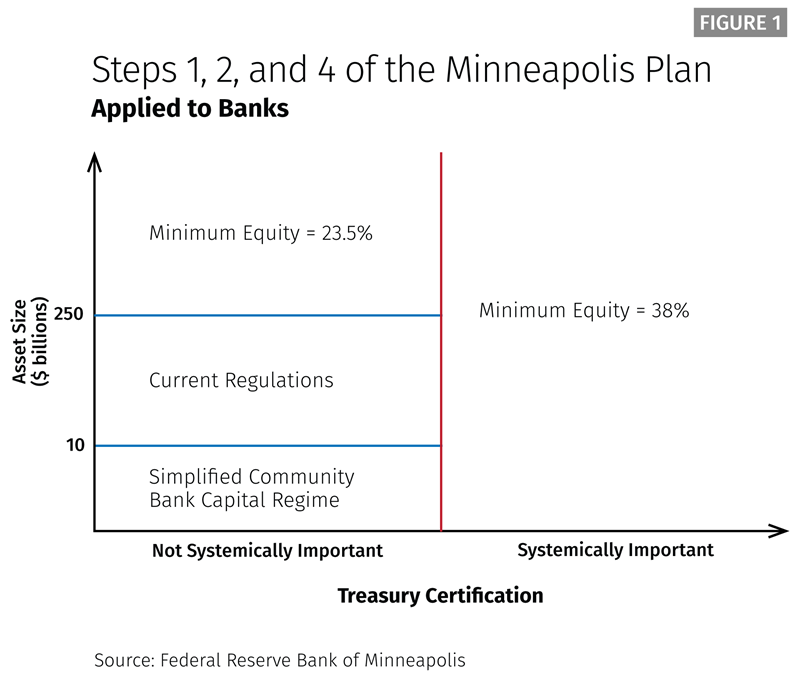

The first way focuses on the treatment of banks and is captured visually in Figure 1. The treatment that banks face under the Minneapolis Plan varies by two factors: asset size and systemic risk. The larger a bank is, the more onerous the capital and regulatory regime it will face. Banks that are systemically risky face a more onerous capital regime than banks that are not. Naturally, firms that are both large and systemically important face the highest capital requirements, while small community banks face the least costly regime, consistent with the risks they pose.

There are three key asset size groupings in the Plan: Banks with assets greater than $250 billion, banks with assets between $10 billion and $250 billion, and banks with assets less than $10 billion. We define banks with asset sizes less than $10 billion as community banks. Under our Plan, these banks will face a simpler and more risk-focused capital regime and regulatory and supervisory regime in general than they face today. Banks with assets greater than $10 billion but less than $250 billion will face the same capital and regulatory regime that they face today. Finally, covered banks with assets greater than $250 billion will have a minimum equity capital requirement of 23.5 percent of risk-weighted assets.

Size intersects with systemic risk to make the final determination of capital and other requirements that the banks face. Under our proposal, the Treasury Secretary will have to certify when banks are not systemically important. The Treasury Secretary will have to review the systemic risk of covered banks but can, at the Secretary’s discretion, identify banks with fewer assets as remaining systemically important. Our Plan’s default position is that community banks will face an appropriate risk-focused level of capital and other regulations, while banks between $10 billion and $250 billion in assets will continue to face the current regime. But it is possible that the Treasury Secretary will deem a relatively larger but not covered bank, with assets greater than $10 billion but less than $250 billion, as remaining systemically important.

It is less clear a priori if banks with assets greater than $250 billion will be designated by the Treasury Secretary as not systemically important. Banks with assets greater than $250 billion that are designated as not systemically important will face a minimum equity capital requirement of 23.5 percent. Banks that do not receive that designation will face an increasing SRC until they reach a maximum equity capital requirement of 38 percent.

Figure 1 summarizes Steps 1, 2, and 4 of our proposal.

Figure 2 summarizes Step 3 of the Minneapolis Plan, illustrating how the shadow banking tax applies to nonbanks, depending on their Treasury certification (systemically important or not systemically important) and their asset size (more or less than $50 billion). This tax, by definition, applies to financial firms that are not banks.

A second way to understand the Minneapolis Plan focuses on the relationship between the two capital levels the Minneapolis Plan imposes on banks. Our Plan has a minimum capital requirement (Step 1) and a higher SRC level of capital (Step 2). The minimum capital requirement applies to banks that the Treasury Secretary certifies do not pose systemic risk. The higher capital level applies to banks that continue to pose systemic risk. Banks that are only subject to Step 1 will no longer be systemically important because many will have responded to the threat of the higher capital standards of Step 2 by lowering their own risk so that they can earn the Treasury Secretary’s certification. They will do this by shedding assets and restructuring their business lines so that their failure cannot inflict systemic harm on the banking sector. But the potential for an individual bank to trigger systemic damage is not merely a function of that individual bank’s assets and liabilities. It is also a function of the strength and capital position of the rest of the banking sector. For example, if an individual $250 billion-plus bank failed when all other $250 billion-plus banks had at least 23.5 percent capital, we believe that failure would likely not pose a systemic risk. However, if that individual $250 billion bank failed when all other large banks were lightly capitalized, that failure could pose a systemic risk. Hence, the minimum 23.5 percent capital requirement for all large banks is essential to enabling individual firms to make themselves no longer TBTF. The higher level of capital is needed for the banks that continue to pose systemic risk to get their chance of failure down to minimal levels.

We now discuss more details of our Plan.

2.1.1 Step 1. Minimum Capital Requirement Proposal.

Key features:

- Only common equity or closely related items count toward the requirement. Common equity is the most robust form of capital for absorbing losses.

- Under current Federal Reserve-issued rules, long-term debt counts toward measures of total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC). We do not believe long-term debt will actually absorb losses in a time of market stress. Historical evidence shows that only bank equity holders absorb losses. In contrast, there is little U.S. evidence to support the notion that bank debt holders will absorb losses. There would be tremendous downside to taxpayers if the government counted on debt holders to absorb bank losses and they did not.

- The 23.5 percent figure will apply to covered banks.

- The proposal also does not vary the minimum level of equity capital by bank or over time. This approach does have a potential downside of imposing similar capital requirements on banks with different levels of systemic risk. Despite this downside, we prefer a less-complex capital regime. Our benefit and cost analysis leads us to conclude that 23.5 percent is the right minimum level of capital that all covered banks should maintain.

- The 23.5 percent capital level is measured as a share of risk-weighted assets. The equivalent leverage ratio is 15 percent of total assets as discussed in Appendix A.

- We chose this level of minimum capital based on a benefit and cost analysis and by referencing current proposals.

- We detail our methodology in Sections 3 and 4. In summary, we consider the benefit of higher capital to be its ability to reduce the likelihood of a banking crisis. We look at historical data on banking crises to calculate how a change in the capital level of banks would reduce the chance of a country having a crisis and requiring government interventions like liquidity support, restructuring, asset purchases, deposit freezes, or other guarantees. We consider such actions to constitute bailouts. In the historical data we review, there is a one-to-one relationship between calling an event a banking crisis and having a bank bailout.

- The cost of higher capital is measured as the reduction in GDP that occurs because the cost of lending goes up and, thus, less lending occurs. Here, we follow the general methodology of the regulatory community and apply it using one of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors’s models of the U.S. economy.

- This benefit and cost approach finds that a minimum capital requirement of about 22 percent maximizes net benefits. That is, it is the point at which the marginal benefits of increased capital equal the marginal costs.

- The exact level of 23.5 percent came from the TLAC proposal issued by the Board of Governors, which has become a final rule. The proposal applied to banks in the United States considered to be GSIBs.9 The proposal set the amount of financial resources that the Board thought GSIBs should have such that they could come out of an extraordinarily stressful period without relying on public resources. A level of 23.5 percent of risk-weighted assets is the level of TLAC that the Board proposed requiring of JPMorgan Chase at the time the proposed TLAC rule was released, which is the highest requirement for any bank. We believe the Board’s sizing of financial resources that covered banks should have is reasonable.

- Step 1 goes into effect five years after enactment of our proposal.

2.1.2 Step 2. Systemic Risk Charge.

Key features:

- Five years after the enactment of our proposal, and every year thereafter, the Treasury Secretary must certify that covered banks are not systemically important. The Treasury Secretary will also have the discretion to review the systemic risk posed by any bank.

- Firms that receive that certification continue to face the minimum capital requirement spelled out in Step 1 of our Plan.

- Firms that do not receive this certification face an SRC, which will increase by 5 percentage points each year until either the Treasury Secretary makes the certification or the equity capital level reaches 38 percent.

- 38 percent equity capital represents the level that is needed to drive the chance of a bailout to 9 percent.

- We encourage the Treasury Secretary to start the analysis of a bank’s systemic risk with the same metrics regulators use today for measuring that risk.

- We believe that many firms currently considered systemically important will restructure themselves to greatly reduce their systemic risk rather than issue equity up to the maximum SRC.

- Firms that do issue equity equal to the maximum SRC will have a much lower chance of failure (and consequent bailout), as well, given their exceptionally high ability to absorb losses.

2.1.3 Step 3. Shadow Banking Tax.

Key features:

- The Treasury Secretary will, within five years, certify if shadow banks are not systemically important and will have the discretion to review all nonbank financial firms when certifying that a given firm is not systemically important.

- A two-tier shadow banking tax rate system mirrors our two-tier capital proposal.

- The tax applies to borrowings of shadow banks.

- A lower tax rate equal to 1.2 percent of borrowings applies to shadow banks with assets that exceed $50 billion that are not systemically important.

- A higher tax rate equal to 2.2 percent of borrowings applies to shadow banks with assets that exceed $50 billion that are systemically important.

- We describe the methodology by which we set the tax in Sections 3 and 4. The general idea is that the government should want the overall cost of funds within the shadow banking system to be the same as in the traditional banking system. We calculate the shadow leverage tax rate so that the 1.2 percent tax rate equalizes the funding costs of banks and shadow banks at the 23.5 percent capital requirement. The 2.2 percent tax rate makes funding costs equal at the SRC of 38 percent. This outcome will discourage the movement of leveraged activity from the standard banking sector to the shadow banking sector. Moreover, this tax effectively removes the tax preference for debt issuance for shadow banks.

- The tax will apply to firms specified in our proposal as nonbanks or shadow banks. We rely on the work of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to identify types of firms that are considered shadow banks. We include hedge funds, mutual funds, and finance companies as shadow banks under this approach. The Treasury Secretary will have the discretion, however, to look beyond this list of shadow banks in certifying that a given financial institution is not systemically important.

- The tax will go into effect five years after enactment of the Minneapolis Plan.

- We make very conservative assumptions in making this calculation. At the same time, we recognize that the analytical framework to support the shadow banking tax is in early stages of development.

2.1.4 Step 4. Right-Sized Community Bank Supervision and Regulation.

Key features:

- Make the capital risk-weighting regime for community banks much less complicated, so that it largely mirrors Basel I.

- Create a default mode for supervision of community banks where supervisors would only review, subject to an exception process, (a) how banks comply with specific laws passed by Congress (and the rules and guidance issued to implement those laws) or (b) operations, policies, or procedures of a bank for which the banking agencies have empirical evidence supporting a correlation with materially weaker bank conditions.

- Impose a wide range of specific risk-focused reforms including but not limited to a longer exam cycle, appraisal reform, reductions in call report collections, and a review of the Current Expected Credit Loss accounting standard.

- Repeal solvency and other noncompliance-related provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act that apply to community banks and that do not have a strong link to their chance of failure.

2.2 TBTF Remains a Critical Threat

In this section, we first define what we mean by too big to fail, explain why TBTF is so important, and discuss why current reform efforts do not end TBTF.

2.2.1 Defining the problem.

Banks are TBTF when their failure or potential insolvency threatens to spill over to other banks and financial markets and ultimately to the rest of the economy. Such spillovers can greatly reduce economic output and throw the economy into a recession or even depression. These spillovers are inherently problematic, even when they do not result in a bailout of banks. But bailouts are part of the standard government response to significant potential and actual bank spillovers, even though it is widely agreed that the creditors of large banks, not the public, should bear the losses of bank failure. Governments view bailouts as the only realistic option they have to address the threat of spillovers that arises when the largest banks get into financial trouble.

This definition of the TBTF problem leaves two general solutions to it. Policymakers must either make it less likely that a bank gets into trouble or limit spillovers when a bank does get into trouble. Government could make banks less likely to fail by requiring that they have more financial resources to absorb losses, for example. Another option for governments to reduce spillovers is to force banks to organize themselves in such a way that their failure is unlikely to spread to other firms. Some have argued that there is a third option: Announce that the government will not bail out banks. We do not think that a mandate prohibiting the government from responding to a large bank failure is credible. Such a restriction on a government response will not work because the underlying problem of spillovers remains, and the government will ultimately have to act or spillovers will cause damage to Main Street.

2.2.2 Importance of TBTF.

The potential economic significance of TBTF is straightforward. As Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari (2016a) argued,

The externalities of large bank failures can be massive. I am not talking about just the fiscal costs of bailouts. Even with the 2008 bailouts, the costs to society from the financial crisis in terms of lost jobs, lost income and lost wealth were staggering—many trillions of dollars and devastation for millions of families. Failures of large financial institutions pose massively asymmetric risks to society that policymakers must consider. We had a choice in 2008: Spend taxpayer money to stabilize large banks, or don’t, and potentially trigger many trillions of additional costs to society.

The view Kashkari expressed seems widely held and explains the global effort to address TBTF in a truly massive way, even if those responses to the crisis impose some costs to the economy.

2.2.3 TBTF remains a serious danger.

Some banks are currently TBTF. There is general, but not universal, agreement on this point simply because post-financial-crisis reform efforts, such as those created by the Dodd-Frank Act, that some believe will end TBTF have not yet been fully implemented. Consider the new resolution regime, which is a cornerstone of the current effort to end TBTF. One option under current law is for banks to go through the commercial bankruptcy regime. In 2016, five of the eight bankruptcy plans submitted by the largest domestic banking organizations were jointly deemed “not credible” by the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and two more plan submissions were deemed as such by one of the two agencies, but not the other. In 2017, none of the banks’ plans were deemed “not credible” by either the Federal Reserve or the FDIC, but four banks were informed that they had “shortcomings” to overcome with their next submission, and all eight were told that more work was required in four areas. While this is an improvement over the 2016 evaluation, there is still material uncertainty about how easy it would be for these eight firms to proceed through commercial bankruptcy in the event of insolvency.10

The central question is, Will banks remain TBTF once the current reforms go fully into effect? Supporters of the reform efforts noted above say no. We disagree.

First, at least some of the reforms put into place seem aimed at preventing a reoccurrence of the last crisis. For example, some reforms focus on aspects of the current derivative, proprietary trading, or securitization markets because of the role they played during the run-up to the crisis. But a lesson from the 2008 crisis is that policymakers will not see the next cause of a banking panic coming, and the exact form the crisis will take will not be the same as the last crisis. (See Kashkari 2016a.)

Second, the current reform effort to end TBTF relies on the TLAC proposal requiring the government to impose losses on debt holders of the most systemically important banks in a stressed economic or financial environment. We believe this proposal is fundamentally unsound and will not work in practice because:11

- The proposal is not compatible with the incentives of policymakers. As Kashkari (2016c) argued, “Do we really believe that in the middle of economic distress when the public is looking for safety that the government will start imposing losses on debt holders, potentially increasing fear and panic among investors? Policymakers didn’t do that in 2008. There is no evidence that their response in a future crisis will be any different.” Some may respond that debt holders under current plans will receive warning that they are at risk of loss. This warning, they argue, will make policymakers more comfortable in following through. But the government has issued such warnings in the past, with regard to so-called subordinated debt holders, and did not follow through in a crisis. Unfortunately, these warnings are not credible. This point was proved most recently when bank debt holders in Italy received protection despite holding debt designed to be “bailed in.” (See Kashkari 2017.)

- This approach is more complex relative to our preferred option of requiring covered banks to issue more equity. Equity holders have a long experience of suffering losses from bank failures in the United States. The government should just require banks to issue more equity if the government wants a straightforward way of imposing losses on the funders of banks. Requiring the debt holders to effectively recapitalize a failing bank during a crisis just increases the risk of contagion and systemic risk.

- We do not find key specific arguments for requiring debt to absorb losses over equity to be well reasoned.

Some supporters of the current debt-focused plans argue that having a smaller equity cushion will prompt supervisors to act more quickly as the equity is erased by losses. At that point, the supervisors can move the firm into resolution where the debt converts and becomes the equity of the recapitalized new firm, thus avoiding a taxpayer bailout. Supporters of this view believe that a bank funded with more equity will see losses exceeding the equity and thus have nothing left over for the recapitalization of the firm by the government. This argument does not make sense to us. The concern that supervisors cannot act when a firm still has positive equity should naturally lead policymakers to support rules allowing early closure; that is, requiring banks to issue more equity and mandating that government close banks when equity is still positive.12 This is not a novel idea. Indeed, the closure regime before the crisis—called Prompt Corrective Action—required this step. However, it failed because triggers for closure were based on measures of equity that overstated the solvency of weak banks.

Another key rationale for the equity and debt split focuses on the cost of debt versus equity. Requiring banks to issue only equity raises concerns about the cost of regulation because equity costs more than debt. Allowing firms to issue debt, some argue, is cheaper. But this alleged benefit of the debt-focused plans may not come to fruition. The debt securities will end up being priced like equity if the bondholders are actually going to face losses. At that point, the government would have given up the benefits of equity, while society would not have actually received the benefit of cheaper debt.

Finally, TBTF firms have already begun efforts to reduce their capital cushions. Requested payouts post the 2017 stress test “are near 100% of banks expected earnings over the next year.” (See Hoffman and Tracy 2017.) For example, in 2017, Citigroup intends to pay out 132 percent of expected earnings. Similarly, Morgan Stanley’s expected payout ratio exceeds 100 percent of expected earnings.13 Moreover, public statements by a number of TBTF firms reveal their desire to operate with even lower capital ratios in the future. JPMorgan is among these firms, as are Citigroup, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America.

In sum, we believe equity is the best guard against a banking crisis and the related bailout of unsecured bank creditors. Some losses in the future could exceed the high levels of equity our Plan requires. Consider a case where a single bank holding the high level of equity we recommend gets into financial trouble. As a result, the bank suffers losses that exceed its equity. The post-financial-crisis resolution framework could avoid a bailout for that firm if conditions were right (e.g., the overall economy is strong). But we do not think the current regime could avoid a bailout for losses exceeding our proposed high levels of equity during periods of market stress. At that point, we see public recapitalization, at least at the point of crisis, as the most credible response.

2.3 Other Transformative Options and Minneapolis Plan Similarities to Breakup Plans

We began the Ending TBTF initiative with a commitment to review a wide range of transformative changes. We specifically noted three reforms at the outset: requiring more capital, breaking up the biggest banks, and taxing leverage. During the initiative, we heard extensively about these three options. We also heard in detail from supporters of the current regime, including those who would prefer to focus on what are incremental changes in the resolution framework currently under way. We have already explained our reasons for rejecting a stay-the-course approach.

In this section, we describe the similarities between our Plan and those that break up banks. In short, we believe our Plan achieves the same objectives of break-up-the-banks proposals, but through a slightly different route.

2.3.1 Breakup plans, and similarities to Minneapolis Plan.

We heard from supporters of two types of breakup plans. First, we reviewed plans that would put a cap on the size of banks, perhaps as a share of GDP.14 Second, we discussed plans that would limit the types of activities that banks can engage in, which would temporarily reduce their size. Efforts on this dimension include “reinstating Glass-Steagall,” as its proponents often put the issue.

The key similarity between our Plan and breakup plans is that both target the reduction of systemic risk through restructuring of TBTF banks. Step 2 of our proposal would apply the SRC to covered banks that the Treasury Secretary fails to certify as no longer posing systemic risk. The Treasury Secretary could use state-of-the-art measures of systemic risk in this determination, which focus on factors like banks’ size, complexity, and interlinkages. We believe most banks will take the steps necessary to reduce their systemic risk along these dimensions to avoid the SRC. Less systemic risk means less chance of spillovers, which reduces the need for a bailout. The logic and goal just described are the same for breakup plans and the Minneapolis Plan.

Our tax on shadow banks has a similar feature. We have one tax rate for large shadow banks that are not systemically important, as judged by the Treasury Secretary. We propose another tax rate for shadow banks that remain systemically important. This regime encourages shadow banks to make themselves less systemically important.

Superficially, the other similarity between our Plan and many breakup plans is that both do not try to specify exactly how the breakup or systemic risk reduction must occur. However, in our Plan, when banks are deciding if and how they will respond to the SRC, they would have to take account of their sources of systemic risk and spillovers, and also the benefits and costs of their current organization. Our Plan tries to force banks to break themselves up such that the resulting entities are not systemically important. This feature of our Plan could differ from other plans that do not limit the systemic risk posed by post-breakup entities.

The similarities between our proposal and other breakup plans may concern some observers. In particular, critics view breakup plans as potentially ineffective and costly. The plans could be ineffective if they yield a group of smaller banks that would all fail in the face of a common shock, reflecting the potential for many banks to “herd” around the same risk (e.g., commercial real estate or exposure to developing countries). The breakup plans could be too costly if there are very large economies of scale to aspects of banking that are lost when covered banks break up.

We view these potential costs as real, but probably overstated in the context of our proposal. First, we try to account for the potential for a common shock to large banks by ensuring that the minimum equity capital requirement is much higher than it is today. This would make it much less likely that the idiosyncratic failure of one of the covered banks would threaten the solvency of another, because all banks would have very high levels of capital. Moreover, we do not expect all banks that result from a breakup to be mirror images of each other. Just as large banks today follow different business strategies, we expect banks of the future to do the same and thus not have exactly the same exposure to risk factors. This combination of future outcomes suggests that the failure of a few large but not systemically important banks at the same time should have a much lower systemic outcome under our Plan than it would today.

Second, and in terms of economies of scale, we agree that the breakup of certain firms could result in smaller firms that benefit less from such economies.15 But measurement of these economies of scale is statistically difficult given the limited number of mega banks, the fact that they have been in existence for such a short period of time, and the challenge of defining what banks “produce” in the first place.16 Thus, it is not clear if the costs from potential loss of economies of scale are large relative to the benefits from reducing the chance of a crisis. Moreover, the Minneapolis Plan would allow firms to maintain their economies of scale if they funded themselves with a much higher level of equity. If the benefits of scale are very large, then society would continue to gain from them. Finally, we note that the frameworks used by supervisors to measure the benefits and costs of higher capital and other regulations after the 2008 crisis do not view potential reductions in economies of scale as a reason to avoid regulation that could lead firms to change their organizational structure.

There is one key difference between our Plan and some breakup plans. Those calling to reinstate Glass-Steagall do specify a certain form of breakup, precisely the separation of commercial and investment banking. We understand the concerns that motivate this type of reform. The costs of such a reform may not be large, but we do not see this type of activity restriction as reducing the spillover problem that defines TBTF. The historical record suggests that commercial banks without material investment banking activity and investment banks with relatively little commercial banking activity can have high probabilities of failure and can also generate the type of spillover that prompts a bailout.

2.4 Implications of the Minneapolis Plan for Supervision and Regulation Policy

This section reviews two implications of our proposal. First, what does this proposal mean for the supervision of banks that are not TBTF? Second, what does our proposal mean for the various reform efforts already under way?

2.4.1 Implications for community bank supervision.

As noted, reforming the current supervision and regulation of community banks to a system that is simpler and less burdensome but still robust is a key step in our proposal. In short, an effective plan must try to reduce the costs of regulation for community banks while maintaining rigor in responding to excessive risk-taking. A reformed regime for community banks must recognize that the failure of a community bank is unwelcome for its local community but does not pose a systemic risk for the U.S. economy.

The first step for reforming the so-called solvency supervision and regulation of community banks is for Congress to enact the reform Plan we recommend for covered banks. We think reforms for community banks will not occur when the threat from the larger banking system to the economy remains large.

The second step is for Congress to create a separate solvency supervisory and regulatory regime for all banks with less than $10 billion in assets. Three key features of the reformed solvency supervision and regulation for community banks we propose are:

- Simple and appropriate capital standards for these banks. The high level of capital that we propose in Steps 1 and 2 the Minneapolis Plan should not apply to community banks. Instead, community banks should face a lower capital requirement, and the method by which banks must determine their capital levels and comply with this new standard should be as simple as possible. Specifically, we call for a capital regime for these banks where the asset risk-weighting is much less complicated and would largely mirror Basel I. We do not support returning to a period where debt-like instruments can count as “capital.”

- A less-costly and less-complex system of supervision focused on fundamental sources of risk. Community banks face a huge array of complicated and potentially unnecessary solvency supervisory expectations. These expectations cover almost every aspect of bank operations, ranging from how banks interact with vendors to how they calculate their interest rate risk to how they plan for many contingency events. There is also a burdensome process that banks face when they acquire other banks or change their ownership structure. It is not clear that these measures actually reduce the chance of bank failure. Rather, these expectations and rules may just add additional expenses that fall disproportionally on small banks, with little perceptible benefit in risk reduction.

A reformed system of solvency supervision for community banks is possible once TBTF is addressed. This system should be much less complicated and focus only on the key expectations that reduce the chance of failure. For example, this system could concentrate on the amount of equity the bank issues, the rate at which the bank is growing, the concentration and quality of its assets, and the stability of its funding. A much more-focused supervisory solvency system could potentially produce the same benefits as the current system but at a much lower cost. This would then allow community banks to focus on extending safe and sound credit to their local economies.

To be more specific, in this framework, the default mode for supervision would be to review only (a) how banks comply with specific laws passed by Congress (and the rules and guidance issued to implement those laws) or (b) operations, policies, or procedures of a bank for which the banking agencies have empirical evidence supporting a correlation with materially weaker bank conditions (i.e., where ineffective bank operations, policies, or procedures, are associated with worsening of bank conditions).

We believe such evidence exists with regard to certain asset concentrations, funding strategies, interest rate risk profiles, and growth patterns, among other variables. We are more skeptical that such evidence exists with regard to a wide range of other activities and requirements that supervisors currently review. We think such a requirement would reduce costs to banks to a substantial degree without making them more risky.

There may be cases where supervisors cannot readily carry out the empirical analysis to show a correlation between a bank practice or policy and weaker banking conditions. For example, it may be difficult to gather data demonstrating that weakness in an internal audit program at a bank is correlated with future weakness; such data may not exist. As such, we would allow supervisors to have an exemption process to these two limits in our proposed framework, but would expect supervisors to use it sparingly.

We would also support the following specific reforms:

- Moving to a two-year examination cycle for banks that have an overall satisfactory supervisory rating and are well managed and capitalized.

- Eliminating the need for appraisals for well-collateralized commercial loans (e.g., with loan-to-value ratios above an appropriate amount identified by the banking regulators) made by community banks headquartered in rural areas. (Rural areas appear to have very few appraisers.)17

- Allowing all mortgages held in portfolio by community banks to count as “qualified” mortgages under the Dodd-Frank Act.18

- Reducing the call report to items for which the banking agencies can affirmatively show a link to the forecasting of future bank weakness or other clear surveillance benefits.

- Applying the Federal Reserve’s Small Bank Holding Company statement to noncomplex holding companies with assets of $10 billion or less.

- Requiring an independent commission to analyze the benefits and costs of the shift to the Current Expected Credit Loss accounting standard and to opine on the net benefits of modifying or eliminating this standard.

We would retain the right of bank supervisors to examine banks sooner than this cycle, require appraisals, and so on, but would shift the default to these recommendations.

- Repeal solvency and other noncompliance-related provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act that apply to community banks and that do not have a strong link to their chance of failure.

Specifically, we call for community banks to be exempted from the Volcker rule for community banks and either elimination of new Dodd-Frank data collections under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act or the Community Reinvestment Act or legal protections for banks that show a good faith effort to comply with the rules, but have errors in reporting.19

We believe these three changes will make supervision and regulation more effective by focusing on key risks and more efficient by reducing resources allocated to lower-risk activity. The downside of our approach is the potential that supervisors will have to react quickly to a worsening of conditions at a bank rather than catching it earlier under the current regime. We do not see this concern as particularly relevant because we continue to focus on supervision of high-risk areas such as credit and capital, and we allow supervisors to accelerate their reviews if needed.

2.4.2 Implications for Current Reform Efforts, Including Resolution.

As noted, the U.S. government already has under way a massive program to address the TBTF problem, most notably through the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, but also through other efforts. Our proposal largely builds on the current reform effort, which we think could make banks more resilient to a shock that hits a single firm during good times. We seek to modify only the minimum capital requirements and long-term debt/TLAC proposal for covered banks. We also create the SRC and the requirement that the Treasury Secretary certify when banks are no longer systemically important. The capital and other regimes currently applied to banks that fall between our definitions of covered banks and community banks would not change.

Of course, there will be technical interactions between our proposal and aspects of the current reform effort, but these can be addressed at a future date.

A more fundamental interaction, however, concerns the resolution regime currently under development. That regime consists of two components. The first is the so-called living will process.20 The second is the special resolution regime that could apply to systemically important banks when, generally speaking, the commercial bankruptcy regime would not prove effective.21

We do not believe that these efforts will solve TBTF by themselves, but we see them as useful steps that could complement our proposal. The living will regime could make the firms to which we apply our capital proposal, as well as other firms, easier to resolve. The new resolution regime could make it easier to address any remaining spillover concerns once the Minneapolis Plan has been fully implemented.22

Will the combination of the new resolution regime, the Minneapolis Plan, and the other aspects of the current reforms mean that a bailout will never occur? The answer is no. Some risks are impossible to eliminate completely, and assessing benefits and costs is essential to finding the right balance. We believe the Minneapolis Plan reduces the chance of a future bailout as much as possible while passing a benefit and cost test.

As noted above, we do believe that a banking crisis large enough to sweep over the capital wall we propose would justify the government response of providing taxpayer support. We also believe that any reform proposal claiming to solve all future banking crises, regardless of size, is not credible. Some crises are so costly that the only appropriate or available response will be a government backstop rather than a resolution regime. Lastly, we do believe that government support in the future could differ substantially from what occurred during the 2008 financial crisis. These support options are not a focus of our current effort.

Endnotes

7 Shadow banks are defined more specifically in Section 3.

8 In later sections, we note many sources of uncertainty in our calculations and provide several types of sensitivity analysis. Here we note that any analytical effort to determine an appropriate level of capital or tax for systemically important banks and shadow banks with the goal of eliminating TBTF will face significant uncertainty and sensitivity in its calculations.

9 The TLAC proposal as applied to the GSIBs is found at http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/boardmeetings/ltd-chart-20151030.pdf. For the TLAC proposal, see Board of Governors (2015c). For the final rule, see https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20161215a.htm.

10 For an alternative view, see FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg’s statement from April 2016: “In my view, we are at a point today that if a systemically important financial institution in the United States were to experience severe distress, it would be resolved in an orderly way under either bankruptcy or the public Orderly Liquidation Authority.” (See Lambert 2016.)

11 See Kashkari (2016b), discussing his lack of confidence that the contingent convertible debt included in the TLAC plan will actually face losses in a crisis. For additional discussion on the challenge in converting debt to equity in the TLAC context, see Flannery (2016).

12 We do not include a requirement in our proposal to close covered banks when they still have a material positive capital level, but we are open to such proposals.

13 Estimates are based on FactSet data and Wall Street Journal reviews of corporate filings.

14 One prominent breakup plan comes from Simon Johnson of MIT. Johnson’s plan focuses on reorganizing financial institutions into smaller entities so that any potential firm failure would be mitigated by its smaller footprint. Specifically, Johnson proposes capping the largest banks at 2 percent of GDP. As of the third quarter of 2017, the size cap would apply to any bank larger than $390 billion in assets. And if bank boards of directors and senior management did not comply with the size limitation, the bank would be subject to “significantly higher capital requirements.” (See Johnson 2016.)

15 For a discussion of economies of scale in banking, see Hughes (2016).

16 For a discussion of these issues, see Feldman and DeYoung (2010).

17 The Federal Banking Agencies released a proposal to increase the dollar threshold at which a bank must obtain an appraisal for a commercial loan. (See Board of Governors 2017.)

18 We view the qualified mortgage rule to have both solvency and consumer drivers and thus include it in our analysis.

19 We view the qualified mortgage rule to have both solvency and consumer drivers and thus include it in our analysis.

20 For more information on the living will process, see the Federal Reserve Board of Governors Resolution Plans website: https://www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/resolution-plans.htm.

21 For more details on this special resolution regime, see Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2013). For a more detailed description of the Single Point of Entry Strategy, see Federal Register (2013b).

22 Some experts have called for a new chapter of the bankruptcy code (Chapter 14) to allow the code to facilitate the resolution of systemically important financial firms. For a discussion of efforts to reform current resolution mechanisms, see Bipartisan Policy Center (2013).