Energy security is a top U.S. concern, and a lot of folks would love to see this country get above the geopolitical fray of depending on oil from volatile countries. They might just get their wish. It's not manna from heaven, but close: crude from Canada.

It just happens that our friendly northern neighbors are sitting on a lot of the thick black stuff and are happy to have the oil-thirsty United States lined up as a customer. "Every barrel of oil that comes from Canada that's refined in the United States means a little bit more in alleviating the adversarial relationships with other countries," said Gary Hanson, vice chairman of the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission.

It just happens that our friendly northern neighbors are sitting on a lot of the thick black stuff and are happy to have the oil-thirsty United States lined up as a customer. "Every barrel of oil that comes from Canada that's refined in the United States means a little bit more in alleviating the adversarial relationships with other countries," said Gary Hanson, vice chairman of the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission.

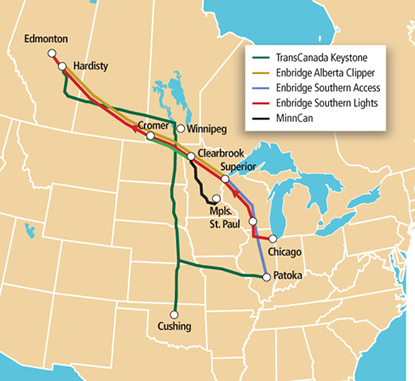

A big missing link, however, is the necessary pipeline infrastructure to transport that oil to U.S. refineries. That's why a number of major pipeline projects are in the works right now, each of which runs through or makes a pit stop somewhere in the Ninth District.

Pipe(line) dreams

Canada is already the world's eighth largest supplier of oil at about 2.5 million barrels of production daily, a majority of which comes from conventional oil sources, and most of which gets pumped to the United States. Thousands of miles of pipeline already snake through the country and the Ninth District, carrying that oil to Midwest and Gulf refineries.

But Canada has huge crude reserves in oil sand deposits. This tarlike oil has only recently become economical to process, thanks to high oil prices and technological advances. Experts believe oil sands production could help Canadian output triple in the fairly near future. Much of that would likely be destined for U.S. refineries—assuming there is pipeline capacity; oil transport infrastructure is already strained without the prospect of new production. In response, several major new and expanded pipeline proposals are in the works to significantly expand capacity to help Canadian as well as district oil producers get their product to market.

Currently, two major new pipelines are in the review and permitting process, as are several expansions of existing pipelines. Each project is at a different stage and runs through different parts of the district. And though hurdles exist, including reluctant property owners along pipeline routes, the demand for new pipeline capacity and the considerable economic effects in the district make these projects a pretty good bet.

The pipelines will also bring numerous economic benefits, like construction jobs in the short term. More important in the long term, the additional transport capacity could be a big benefit to domestic producers in the Dakotas and Montana and offer local and state governments a boost in tax revenue to boot.

TransCanada Keystone Pipeline is in the planning and permitting stages of a massive project to move oil from the supply hub near Hardisty, Alberta, through North and South Dakota on its way to storage and pipeline hubs in Wood River and Patoka, Ill., and further to Cushing, Okla. (see map). Estimated at $2.1 billion, the Keystone pipeline could transport 435,000 barrels of crude oil per day to U.S. markets. The total length of the proposed pipeline is 1,830 miles; about 1,070 miles will travel through the United States.

Sources: TransCanada Keystone Pipeline LLC; Enbridge Inc; Minnesota Pipeline Co.

Robert Jones, company vice president, noted that the oil industry is very active right now because of strong U.S. demand and the attractiveness of a stable supply in Canada. Keystone has held community meetings along the routes in affected states and thus far has not encountered opposition. Final approval is anticipated by the end of 2007, with construction beginning in spring 2008 and completion late in 2009.

Enbridge is another firm working on new and expanded pipelines that weave into the district. It already operates the world's longest crude oil and liquid petroleum pipeline system in Canada and the United States. Perhaps the most ambitious proposal is the $2 billion Alberta Clipper pipeline, which will take crude from Alberta to Superior, Wis. Introduced in February 2006, the Alberta Clipper involves construction of a new 990-mile crude line primarily following Enbridge's existing rights of way. Initial capacity will be 450,000 barrels per day, with ultimate capacity of up to 800,000 barrels per day.

Coming out of Superior, the pipeline project becomes known as Southern Access and moves crude oil to the Chicago area via a 321-mile leg expected to cost $487 million. Enbridge plans to have the entire pipeline in service in 2009, once the Southern Access program is completed and as crude oil supplies from Western Canada continue to increase.

Another concurrent project involves running a pipeline, called Southern Lights, from Chicago back through Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. This line will bring light hydrocarbons, or "diluents," to Edmonton for distribution to the Alberta oil sands area, where they will be used to dilute heavy crude oil and bitumen (the thick, tar-like form of oil found in the oil sands) to a consistency thin enough to be more easily transported by pipeline.

Other major new pipelines are being proposed, but are less certain to get built. For example, Altex Energy is looking into a multibillion-dollar pipeline from northern Alberta to refineries in the Gulf Coast, and running somewhere near and along the border of Montana and the Dakotas. First proposed in 2005, this project is still in preliminary stages.

In addition to these blockbuster pipeline projects, a few expansions are already under way to improve capacity for domestic oil producers in the district.

An Enbridge subsidiary in North Dakota is building a 52-mile pipeline there that parallels an existing line in northwestern Williams County and includes 10 new or upgraded pump stations and additional tanks. These projects amount to an investment of about $42 million, and up to $60 million with associated improvements. Upon completion in late 2007, the entire North Dakota system expansion project will increase capacity from 80,000 to 110,000 barrels per day for Montana and North Dakota crude oil production.

Enbridge's North Dakota pipeline travels to Clearbrook, Minn., where a line owned by Minnesota Pipe Line funnels it to two refineries south of the Twin Cities. This section of transport is also slated for significant expansion. In February, the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission approved an additional 300-mile, $300 million pipeline. Dubbed the MinnCan project, it will increase pipeline capacity by 47 percent (165,000 barrels a day) to the Flint Hills Resources refinery in Rosemount and Marathon Petroleum Co.'s refinery in St. Paul Park. Capacity could reach 350,000 barrels per day over the course of the next several years if pumping stations are added.

Good news for district producers

The additional pipeline capacity will mean some relief for Williston Basin and other regional oil producers. Lately, increasing volumes of Alberta crude have intensified competition for pipeline space and negatively affected the prices paid to oil producers in western North and South Dakota and eastern Montana.

The matter is akin to farmers and railroads. When boxcars are scant, farmers have to pay railroads higher rates to get grain to market. For oil producers, the cost of tight pipeline capacity comes in the form of lower prices they receive from pipelines for the oil itself.

The new pipelines mean more Canadian oil will bypass local markets and ease a bottleneck that has kept oil prices lower for district producers.

Because of pipeline constraints and other factors, North Dakota producers have typically received about $3 less than the average price paid for benchmark West Texas crude on the New York Mercantile Exchange. But as oil prices have risen over the past few years, so has that price gap as more production has come online and strained pipeline capacity further, briefly spiking to almost $18 a barrel at one point.

Although district oil producers may never reach parity with West Texas crude prices, the extra pipeline capacity will improve the prices district producers get for their oil, said Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota Industrial Commission, Department of Mineral Resources.

On the whole, district oil production has been increasing because of high oil prices on the broader market, but some North Dakota oil producers have lowered production and closed down some rigs, according to Helms. He added that the rig count in North Dakota is down by nine from last fall, and new drilling has been impeded directly by the pipeline capacity shortage. While expenses have increased, prices paid to producers have dropped, largely due to transport constraints, Helms said, and some producers simply cut production or are reluctant to invest in new rigs. It's the same story in Montana. Tom Richmond, administrator of the Montana Board of Oil and Gas Conservation, said producers there have seen a discount to market price of about 25 percent to 30 percent. But he expects that gap to narrow with additional pipeline capacity.

Refineries pumped up

Increased pipeline capacity also offers an opportunity to reverse the decades-long decline in refining capacity. Though no new refineries are expected immediately, existing ones will have a great incentive to expand. To accommodate the thicker, low-gravity oil from tar sands, some plan to retrofit existing refineries rather than going through the costly, cumbersome, long-term process to construct new ones.

Many U.S. refineries are already operating at over 90 percent capacity, Helms said, and many are looking at expansion or have already expanded. He added that while no new refineries have been built in more than 30 years, plant expansions over time equal the capacity of 17 new refineries.

Dave Podratz, refinery manager for Murphy Oil in Superior, Wisconsin's only refinery, said the Upper Midwest "is ripe for refinery expansion." Murphy gets all its oil through an Enbridge pipeline. When he got into the business 20 plus years ago, Podratz said, there were more than 320 refineries; now that number is under 150. With Enbridge bringing additional crude into the Midwest, Podratz said, there will have to be refinery expansion. He cited already-announced plans for refinery expansions in Illinois and Indiana. Murphy Oil is looking at the feasibility of upgrading its Superior facility, which is very small—about 35,000 barrels of oil per day versus 200,000 barrels at Chicago-area refineries.

Montana hosts four refineries, three in the Billings area and one in Great Falls. The CHS refinery in Laurel (near Billings) has applied for an air-quality permit to build a processor to better refine Canadian so-called sour crude (oil with higher impurity levels). The project would cost $325 million and take two years to build.

ConocoPhillips is looking at retrofitting its Billings refinery using technologies to process the heavier, dirtier crude. The company expects to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on the project, which would expand capacity and refining capability and is prompted by a ConocoPhillips joint venture with a Calgary-based corporation.

The Montana Refining Co. in Great Falls, the state's and perhaps the nation's smallest refinery, processes about 9,000 barrels of oil per day. It was purchased last year by Connacher Oil and Gas of Calgary, which plans to develop extensive oil sands leases in northern Alberta. Some of that oil eventually could be refined in Great Falls. It is in the process of building a new 150,000-gallon asphalt tank.

North Dakota's only refinery, Tesoro in Mandan, normally processes 55,000 to 60,000 barrels per day of largely North Dakota and Montana oil. It has no plans for expansion. However, the Three Affiliated Tribes are in the planning stages of building a refinery on the Fort Berthold Reservation near Makoti.

North Dakota's Helms noted that what's really driving pipeline expansion is that Canadian companies want to get to the Gulf Coast, where there's a 7-million-barrels-a-day refining infrastructure that distributes to even larger U.S. markets, and refineries there are already preparing for that eventuality.

NIMBYs, higher tax revenues

Though there is a lot of support for expanded pipelines, these projects are not without their critics.

The MinnCan project would follow the existing pipeline for part of the route, but the final leg circles around and through Twin Cities suburbs and has raised concerns by homeowners, organic farmers, environmental groups and others. While the company has reached agreements with 70 percent of the 1,100 landowners affected and the project has been approved by the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, it may still be challenged in court. Opponents cite an oil spill of 134,000 gallons in June 2006 near Little Falls and other accidents over time as a basis for their concerns.

Enbridge's Southern Access extension in southern Wisconsin has run into a buzz saw as well. Dave Siebert, director of the Department of Natural Resources Office of Energy, noted that environmental groups asked the courts for a stay, charging that the state's environmental analysis was inadequate. Their request was denied, but a lawsuit to stop the expansion may be in the offing, buoyed by an early January pipeline rupture that leaked about 52,000 gallons of crude oil across a frozen field near Curtiss, Wis.

Still, most states and communities appear eager to accept the pipeline systems because they bring extra revenue to a region by way of taxes, construction jobs and spinoff dollars. The MinnCan project, for example, is expected to employ up to 1,000 workers during the construction period, according to Larry Hartman at the Minnesota Department of Commerce.

Denise Hamsher, public affairs director for Enbridge and its affiliates, said twice that many workers were hammering away at the company's new pipeline in Wisconsin as of February. During construction, many workers need temporary lodging, and lots of goods and services are bought locally, both for project use and by workers during their off time.

And then there are the taxes. Last year, Enbridge paid over $11 million in taxes in Minnesota, and that will increase substantially with two new pipelines, Hamsher said. The MinnCan project is likely to amount to several million dollars in property taxes, said Hartman. Jones, with the TransCanada Keystone project, predicts that pipeline would bring North and South Dakota each $5 million to $6 million in taxes annually.

Bill Ballard, CEO of Ballard Petroleum Holdings in Billings, Mont., noted the state has about a $1 billion budget surplus this year, which is largely attributable to energy businesses and the generally high price of crude oil over the past year and a half. The state gets about 9 percent to 10 percent on what the producer sells, and then refineries and pipeline operators also pay taxes, Ballard said. "The main thing is that Montana interests—producers, landowners and the state—all three benefit if there's more access to pipelines," he said.

May I help?

Some states are starting to investigate whether there is a larger role for government to play to perhaps expand the oil industry. A bill wending its way through the North Dakota Legislature would establish the Pipeline Transportation Authority, which would "provide for the planning, constructing, owning, financing, maintaining, operating, and disposing of pipeline facilities and related infrastructure." The authority would have staff dedicated to working with Canadian oil companies to explore how North Dakota producers can tie into pipelines, among other issues, said Helms.

Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer has met with Canadian oil producers to work on pipeline issues that would allow greater access of local oil to local refineries, and to help smaller producers secure better financing for exploration and drilling. Oil exploration is a risky business, said Ballard, of Ballard Petroleum, noting that producers exploring new production have a 90 percent chance of losing their investment. Thus, they are always looking for partners to share the costs and, Ballard suggested, smaller Canadian producers are looking for partners. "There are tremendous opportunities on this side of the border, in the Williston Basin," Ballard said.

The Schweitzer administration is also looking into the possibility of constructing new oil refineries to capture some of that crude oil passing through the state. The state has hired a consultant to look at possible sites in seven communities in eastern Montana.

So despite the fact that not everyone agrees that more oil pipelines are wise or necessary, most believe that the potential environmental hazards don't equal the positive effects on the local and state government coffers. South Dakota's Hanson said the economic benefits really don't cost the state or communities anything: "It's like you being in college and your dad sending you money."