Of the many unsolved problems in economics, the “exchange-rate disconnect puzzle” is among the most vexing. Exchange rates are inexplicably volatile and seemingly disconnected from macroeconomic factors like interest rates, output, and inflation. It’s a mystery that has preoccupied researchers for decades.

Many economists have suggested that price rigidities—inflexibility in price adjustment—might account for the disconnect. Other scholars have proposed alternative solutions. But no one has settled the debate.

“These answers are typically very clever but far from thoroughly convincing, and so the puzzles remain,” wrote economists Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff in an influential 1995 paper. They proposed that trading costs for final goods were at the heart of the issue, and most research since then has focused on final goods. But in a 2008 interview, Rogoff said little headway had been made: “The glass is 95 percent empty, 5 percent full.”

A novel direction

A new paper takes a very different tack, focusing on primary commodities rather than final goods, and it appears to provide a cogent, if partial, explanation. Global shocks to prices of primary commodities (like petroleum, fish, timber, and gold) can differentially impact the domestic costs of manufacturing and final goods costs in various nations, thereby shifting exchange rates among them. And since commodity prices are volatile—thus their exclusion from the Fed’s preferred inflation measure—that’s reflected in exchange rate volatility.

In “Real Exchange Rates and Primary Commodity Prices,” a staff report by Juan Pablo Nicolini of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, with Joao Ayres of the Inter-American Development Bank and Constantino Hevia of Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, the exploration of the relationship between commodity prices and exchange rates begins with “a simple general equilibrium model.”

And it is indeed simple (for an economist): On one side, the exchange rate between countries 1 and 2, adjusted for inflation. On the other, productivity levels in the two countries, prices of natural resources, and prices of primary commodities. Coefficients for the commodity prices vary by country, reflecting their respective production structures and macroeconomies.

The model also features a third economy representing the rest of the world. It’s included as a device to generate excess demand for primary commodities. By mathematically shocking international demand, the economists can generate volatile and persistent commodity prices and observe the impact on exchange rates.

The model reflects the theorized mechanism by which shocks to commodity prices can impact exchange rates. The idea, again, is that shocks to the cost of primary commodities affect exchange rates as well because commodity price fluctuations impact manufacturing costs and prices, which in turn influence final goods costs and therefore final goods prices. And because changes in primary commodity prices may well have differential domestic cost effects in any two countries, commodity price changes will affect the exchange rate between them, reflected in their volatility and persistence.

What do the data say?

The next step is an empirical exploration of the relationship between exchange rates and commodity prices. Are they closely related, as this theory contends? Using regression analysis, the economists measure how much of the variability in exchange rates can be explained by shocks that also affect commodity prices. The data reflect exchange rates between the United States and three trading partners, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom, from January 1960 to December 2014, and international prices of 10 primary commodities.

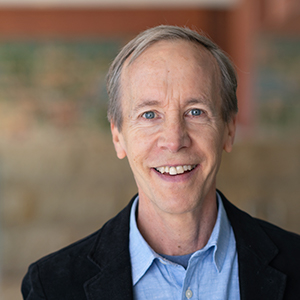

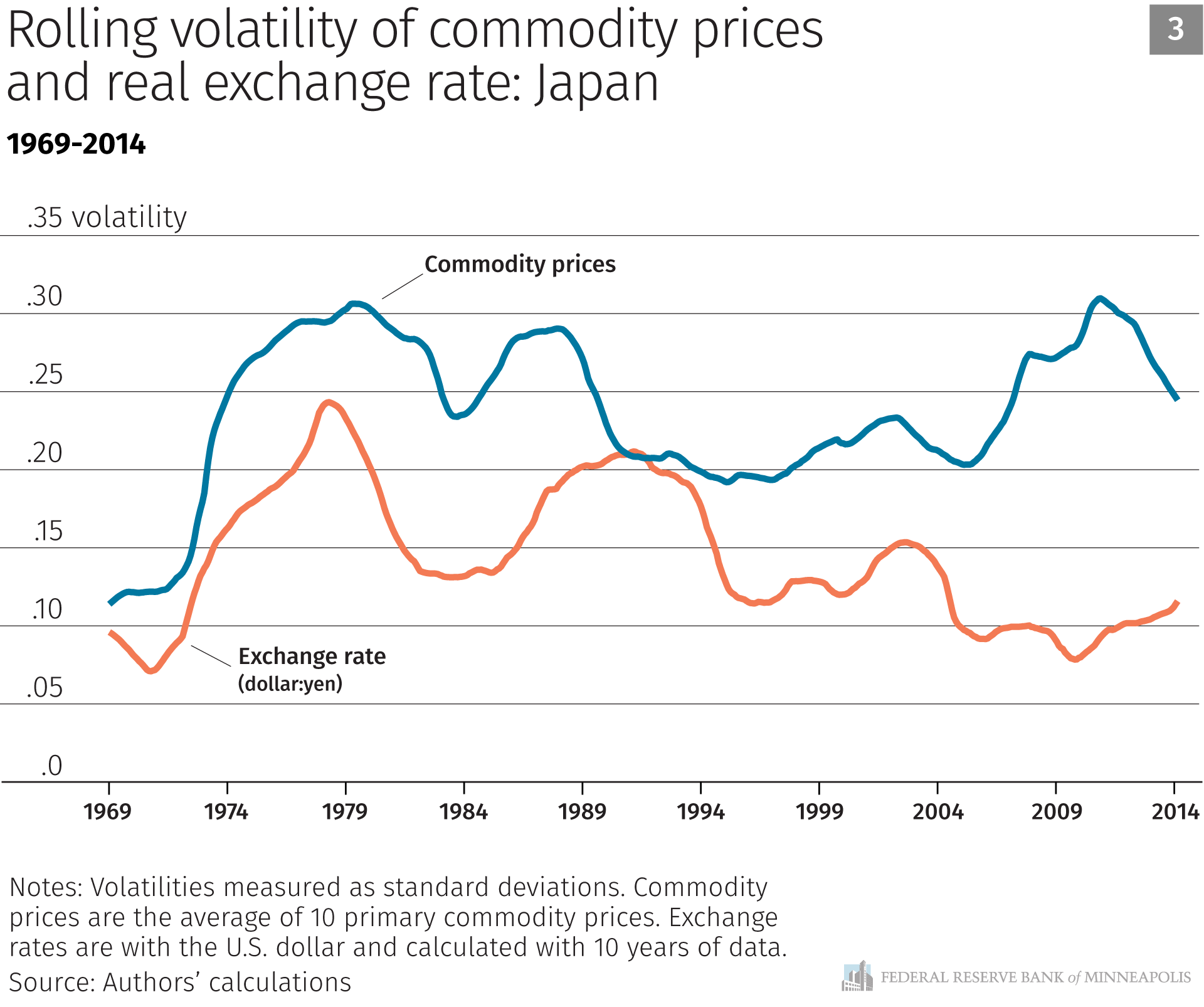

The economists find that commodity prices are more volatile than exchange rates and also that exchange rate volatility is high when commodity price volatility is high. But more significant are the regression results, the degree to which commodity price volatility can account for the exchange rate volatility. Results vary by country but, in all cases, there is substantial explanatory power. Price volatility for 10 commodities explains 48 percent, 63 percent, and 57 percent of U.S. exchange rate volatility with the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan, respectively, over the entire time span, and as much as 95 percent for some subperiods.

Simplifying analysis to just four commodities entails little sacrifice. “We can still account for between 33% and 56% of the volatility of real exchange rates.” The close match between rates and prices is illustrated in Figures 1–3, showing for each country the volatilities of exchange rates and of prices for 10 commodities. Further tests confirm the strength of the relationship, with a fit the economists consider “remarkable.”

The final step is to use the model to explore whether their theorized mechanism can replicate actual data. That is, to what degree can it account for the “disconnect”—the inexplicable persistence and volatility of exchange rates?

Refining and calibrating the model to match the economies of the United States and Japan, the economists analyze the standard deviation (volatility) and autocorrelation (persistence) of the real exchange rate. “The result is striking,” they write. The model delivers results that are extremely close to actual data. Standard deviation is 32 percent in the model and 37 percent in the data. Autocorrelation is 0.99 and 0.96 in the model and the data, respectively. The R-squared coefficients (indicating the proportion of variation explained) are 93 percent in the model and 80 percent in the data.

When they drop primary commodity prices from the model, it fails entirely. Standard deviation is just 2.8 percent rather than 37 percent in the data, autocorrelation is 0.07, not 0.96, and the R-squared coefficient drops to 2 percent. The results are a strong validation of the ability of primary commodity price movements to explain exchange rate activity.

Progress, and a long path ahead

The research thus appears to be a major step forward in resolving the disconnect puzzle. The economists present empirical evidence that a common factor moves both primary commodity prices and real exchange rates; shocks that move just four commodity prices can account for between one-third and one-half of exchange rate volatility over a half-century and much more over shorter periods. And their model incorporating shocks to productivity and commodity demand successfully replicates actual volatility and persistence of exchange rates.

“The model,” they write, “can go a long way in reproducing the volatility and persistence of the [real exchange rate].” And it suggests that overlooking primary commodity markets, as much research to date has done, is unwise for those seeking to explain exchange rate movements.

Theirs is an innovative approach to a stubborn problem, and it seems to hold promise. But is it simply “very clever but far from thoroughly convincing”? Time—and more research—will tell. As Ayres, Hevia, and Nicolini conclude, “This first exploration … went a sizable way toward solving that problem and placed a long research path ahead of us.”