Manufactured housing has a long line of colorful euphemisms (c'mon, admit it, you know a couple). Even the upscale version of manufactured housing—the aptly named double-wide—has unflattering connotations.

Despite improvements in quality, a move to larger, more expensive units and the simple fact that it provides a path for many to the American dream of homeownership, manufactured housing still suffers from crazy-uncle syndrome within the housing industry. Almost regardless of improved appearance and function, the old images and stereotypes persist.

So say it out loud, just so we can move on: trailer trash.

Related articles in the fedgazette: |

Unless you own a manufactured home or work in the industry, you're unlikely to know much about this niche of housing or the parallel world it exists in compared with traditional single-family housing, particularly when it comes to financing and land-use regulations.

Indeed, many people still refer to the industry as mobile homes, despite industry efforts to distance itself from the word and its trailing image, and the fact that there is almost nothing mobile about these houses anymore, save for the highway ride from factory to field. The stereotypes remain in part because the industry began as something very different from its current form in both appearance and function. As the product of a fledgling industry, a mobile home was something you attached to your car or pickup. It was semipermanent housing for transient folks, like migrants moving from job to job doing construction or harvesting.

Slowly, the industry has evolved, focusing less on the "mobile" and more on the "home" over time. That's one reason the industry tries to steer people away from the term "mobile homes," preferring "manufactured homes" in its stead as a more accurate and less pejorative description. (See sidebar for technical and other subtle differences among housing types that are produced in the factory, rather than on-site.)

In the 1990s, thanks to improvements in design and quality and greater availability of credit, the industry found its groove. Sales exploded, and it appeared for a brief moment that the manufactured home might finally become a viable option for mainstream home buyers.

But the industry got hammered starting about 1999, falling hard for the next half-decade and only now feeling like it might be able to push off the bottom. Some reasons for the slump are simple: Underwriting standards were loosened as lenders fought each other for market share, and too many loans were made to too many buyers who couldn't afford the houses they were being sold, aided at times by unscrupulous dealers preferring high-profit sales over an industry's long-term reputation.

But other broad and complex reasons keep the industry from becoming a choice of more home buyers despite clear cost advantages over site-built (also called stick-built) homes. In many ways, buying a manufactured home is still more like buying a car than buying a traditional home. As such, the manufactured home industry is still battling—with the buying public and even within its own ranks—the legacy of its bygone mobile roots.

But change also continues in the industry—led in part by the industry's example in district states—that might eventually bring the manufactured home to a subdivision near you, and you might not even mind it.

New kid on the block

When people think of manufactured homes, most are still stuck in the 1970s—they imagine a 14-by-70-foot, metal-clad mobile home in a trailer park.

In some ways, the industry has changed dramatically. Not only have exterior designs changed—particularly for double-wides, what the industry calls "multisection" homes—but interior amenities now run the gamut like in any site-built home.

"There's very little in a site-built home that you can't duplicate in a manufactured home," particularly for interior amenities, said Chad Evans, president of Centennial Homes in Aberdeen, S.D. The dealership began in 1969 as a single-lot retailer. It opened two additional outlets in the 1980s and three more from 1997 to 1999, which gave the company sales outposts in North Dakota and Montana as well as a greater home-state presence. The company's Web site estimates that the firm is responsible for about 45 percent of all manufactured homes shipped annually into the state. "The product has come a long ways. I don't think we have people getting sold a piece of junk," said Evans.

But the industry is still tied to its roots—or more accurately, to its chassis. One of the basic differences from site-built homes is that manufactured homes are built on a permanent chassis. This is required for delivery purposes and hypothetical future moves (which are rare today, especially for new homes, according to the industry). Federal regulations enforced by the Department of Housing and Urban Development restrict the length, size and height of an individual section so it can be transported safely on highways and under bridges.

As a result, builders of manufactured homes (also known in the industry as HUD-code homes) are boxed in from a design standpoint. Though options for exterior features and materials have been upgraded in many cases, you can still see the family genes from earlier models.

The biggest selling point for manufactured housing is its general affordability, starting from about $60,000 for a multisection home and $35,000 for a single-wide. Those prices don't include land, but are still significantly cheaper than a site-built home, even on a square-footage basis. Crunching U.S. Census data, the Manufactured Housing Institute estimates that costs per square foot for manufactured homes can be half those of site-built homes. Other estimates and sources claim the average manufactured home is 10 percent to 25 percent cheaper than a site-built.

That's not to say you're necessarily getting the exact same house for less money. The difference in cost between an "average" manufactured home and a site-built one comes mostly from the presence (or absence) of certain features. Things like garages, basements and porches are often standard issue in site-built homes and are priced into the cost accordingly. With a manufactured home, the buyer is getting just the home, from floor to rooftop. A buyer can add features like a garage or basement, but these add-ons often are not handled by dealers and thus not included in the average selling price. The same is true even for home installation, which is typically handled by a licensed third party rather than the dealer, though some changes are afoot in terms of so-called full service dealers. (See "Dealer, heal thyself.")

Evans acknowledged that for an identical home—in terms of square footage, materials, amenities, features and so on—there might be some cost advantage of manufactured over site-built, "but it would be slight," maybe 10 percent, coming mostly from bulk material purchasing and delivery, lack of weather-related delays, and general speed and efficiency in factory-based construction.

Still, the unique niche for manufactured housing is its ability to "go low," if you will. By forgoing certain options or amenities, a manufactured home buyer has the ability to keep the final price truly low for affordability. But local land-use regulations typically require (and new owners almost universally demand) numerous features in site-built homes that are often considered extras in manufactured housing. This gives manufactured housing much more flexibility in terms of what a buyer can afford.

The boom, then the burst

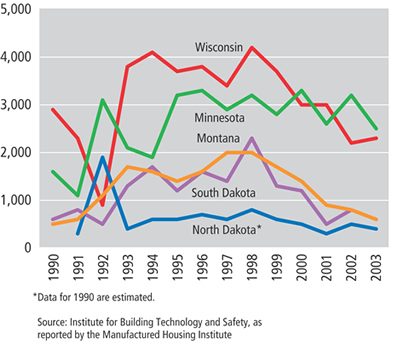

Armed with a better, more sophisticated product, aided by an improving national economy and offering an alternative to rapidly escalating prices for traditional housing, the industry went on a tear starting about 1990. By 1998, nationwide "placements" (or deliveries to buyers) almost doubled to 373,000—good for a 20 percent share of the market for new homes. Placements in district states grew from about 5,600 to 12,500 units during the same period (see charts).

New Manufactured Home Placements

At Centennial Homes, the entire 1990s "was an upswing. Every year pretty much beat the last (one)," said Evans.

Was manufactured housing ready for Main Street? Not quite. It seems this housing growth was built on a foundation of sand that quickly gave way, exposing serious flaws in the industry. Blame is easy to hand around: Too many buyers got in too deep too quick, helped by aggressive sellers hawking too many homes to buyers with questionable credit histories, but who nonetheless qualified for purchase loans thanks to a bull-rush into the industry by lenders who wanted a piece of this hot housing market.

Comparatively few lenders specialize in home loans for manufactured homes. Still, their numbers more than doubled (from 11 to 24) between 1993 and 1998, according to government figures. Subprime loans were also a popular financing option for manufactured homes, and such lenders grew sixfold from 1993 to 1998, to more than 250 firms.

As competition for loans rose, loan standards were relaxed. Average length of loans increased, and 30-year loans—unheard of in earlier days—became more common. Down-payment requirements were lowered, and lenders started buying down interest rates with points.

"It was really a facade boom. ... If you had a pulse and could sign your name, you could get a loan" for a manufactured home, Evans said.

The problem is that such loan incentives—common for site-built homes—didn't translate very well financially for the manufactured home industry. The problem? A little matter known as appreciation. The traditional housing market has come to expect it as a birthright. In manufactured housing, "because of other factors, we haven't had the appreciating model," said Chris Stinebert, president of the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI).

Appreciation makes all the financing difference in the world. Rapid appreciation means that mortgage companies have virtually "risk-free financing. ... A bank can repossess [a site-built home] after just two or three years and still get all of their money back. With manufactured housing you can't," Stinebert said. Owners of manufactured homes might live in them for 15 years "and have no equity in their house" because of slow appreciation (even depreciation in some cases) and the fact that loans were being approved for more than homes were worth, sometimes much more. As a result, Stinebert said, some buyers "were being buried into their homes."

In short, the lending sector wasn't pricing loans appropriately for the underlying risk. By 1999, delinquencies and repossessions began to creep up, though by how much is tough to say. "We do know [repossessions] were extremely high," Stinebert said. But no hard figures are available because lenders had no uniformity regarding the definition of repossession, in part because many "were trying to hide" the fact that their portfolios were loaded with bad-performing loans for manufactured housing, he said.

Estimates from several industry sources put annual repossession at between 80,000 and 100,000 for several years during this decline. A 2005 report by Lehman Brothers said repossessed inventory went from $300 million in January 1999 to $1.3 billion by the end of 2002, with recovery rates (the percentage of loan value recovered by sale of repossessed collateral) dropping "as low as 25 percent during the period."

Compounding the decline was the fact that additional production capacity had been brought online, with the number of home-building plants nationwide jumping better than 30 percent from 1990 to 1998. As the industry peaked and then began to fall, production (called "shipments" by the industry) stayed higher than total sales, and dealer inventories ballooned from continued shipments from manufacturers and a flood of repossessions (see chart).

U.S. Manufactured Homes in Thousands

And it wasn't just a bad year or two. Dealer sales plunged for six straight years—down some 67 percent from 1998—to levels unseen for decades. In district states, placements returned to about 6,000 units. And remember, this nose dive took place at the same time that the site-built market skyrocketed.

The pain has been spread through dealers, lenders and manufacturers. The number of active plants nationwide dropped from 330 in 1998 to just 210 last year. Production of manufactured homes in Wisconsin grew 40 percent from 1990 to 1995 to about 4,500 units and then steadily hemorrhaged to just 1,100 units last year, well below preboom levels, according to MHI data.

Lenders played a game of follow-the-leader into and out of the manufactured home industry. Fitch Ratings reported that as of January 2003, "an overwhelming majority" of lenders that had entered during the boom were no longer in the business.

Many in the industry believe they've seen the bottom. Stinebert said the industry is "living year-to-year right now," but added that he expects annual growth this year of 8 percent to 13 percent. "We'd like to have a steady recovery."

Whether that can happen depends on a lot of things going right for the industry, including an improving economy and job market for moderate-to-low-income households, the industry's bread-and-butter clientele. The slump has also laid bare the fact that manufactured housing faces unique obstacles in becoming a mainstream choice for home buyers—most of them stemming in some way from the industry's legacy as footloose housing.

Idle chit-chattel

One might have thought that low interest rates since about 2001 would have boosted manufactured housing like it has the housing industry in general. Ironically, many believe low rates have done manufactured homes more harm than good by making its main competitor—stick-built homes—more affordable.

More important, however, low interest rates couldn't pull the manufactured home industry out of its dive because financing for this housing sector differs significantly from that for site-built housing. Nationwide, relatively few buyers of manufactured homes finance their purchase with a conventional or government-backed real estate mortgage (though more do in the district—more on that later). This means low-interest mortgages of the past few years have been so much paper confetti to many manufactured home buyers.

And in fact, manufactured housing has never quite been on equal footing with site-built housing when it comes to financing. Because of its mobile legacy, manufactured housing has historically been purchased and titled as personal property, financed by so-called chattel loans-derived from the word "cattle" to intimate property that is movable and personal, like cars and furniture. "Real" property—land and homes affixed to permanent foundations—is fixed and immovable.

Big deal? Absolutely, because personal property (or chattel) loans have many downsides for the consumer, while real property (or real estate) loans in general offer more benefits. The distinction becomes more obvious in the simple fact that when bought as personal property, a manufactured home is more like a car than a home.

In 2003, only about 35 percent of all manufactured home loans were titled as real estate, according to Census figures. The reasons are many. Some homes are placed on leased land in parks or communities, and few lenders are willing to finance a home as real property if it doesn't include the ground beneath it; indeed, homes in lease parks are increasingly being threatened with eviction as park owners see larger profits in other land uses.

There are some advantages to chattel loans. Though credit scoring is more common today than during (and now, because of) the 1990s boom, personal property loans in general are easier to qualify for than real estate loans (again, think of a car purchase). These loans typically are approved in a day or two, with few of the hassles or documents required of a traditional mortgage. But that speed and availability comes at a cost. On average, research suggests—and sources confirmed—that interest rates for chattel loans run 2 to 5 percentage points higher than for real estate loans. In other words, while manufactured housing is affordable in terms of purchase price, much of that affordability is often eroded by higher financing costs.

Real estate financing also offers other important, and more subtle, advantages over chattel financing, particularly in terms of consumer protection. For example, real estate transactions are subject to laws like Truth in Lending and the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act, which provide more transparency and disclosure to the purchase transaction than is typically seen for chattel loans. The Real Estate Settlement Act requires appraisals and keeps a lid on fees for buyers of site-built housing, as well as commissions paid to sellers. The law also offers owners some safeguards from being thrown out of their homes in case of loan delinquency and creates a very deliberate foreclosure process. Manufactured homes financed as personal property enjoy few of these safeguards, with reports of people literally being carried away with their home, throwing possessions out of the home before it gets towed away.

Even resale is more complicated for manufactured homes titled as personal property, because the traditional system deals only with real property, not personal property. As a result, many owners of manufactured homes are forced to sell their own unit. A January 2005 industry outlook by A.G. Edwards & Sons pointed out, "Unlike site-built homes and even apartments, there is no nationwide network of real estate brokers buying and selling manufactured homes. ... Real estate brokers have little-to-no incentives (i.e., commissions) to spend time in this arena. ... It would prove difficult (if not impossible) to name a single real estate brokerage operation that has a meaningful and profitable operation focusing on manufactured homes in the U.S."

Chattel loans also preclude a buyer's ability to tap into the many government efforts to encourage homeownership. Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae—agencies created by Congress to encourage homeownership at all income levels and ubiquitous in site-built housing markets—have little involvement in manufactured housing (see sidebar). A 2002 report on manufactured housing by the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation noted, "Given the enormous emphasis on low-income, first-time home buyer programs, and on policy efforts focused on opening mortgage markets for these buyers, the lack of attention manufactured-housing finance receives is somewhat ironic."

In Montana and South Dakota, for example, the use of subsidized, first-time home buyer programs is small among manufactured home buyers, in part because eligibility requires homes be put on real (not leased) property and placed on a permanent foundation. In Montana, only 5 percent of home buyer program loans go to purchase manufactured homes, according to a Board of Housing official—this for a state where HUD figures show 14 percent of all housing units are manufactured homes.

Wisconsin has similar financing programs for manufactured homes, according to Ross Kinzler, head of the state industry association called Wisconsin Housing Alliance, who responded via e-mail. But the fact that homes have to be on real property ignores the 53,000 families who live on leased land in manufactured home parks. These families "are at the bottom of the income scale (and) are homeowners, yet don't qualify for most state or federal programs," Kinzler said. "Could it be income discrimination? Could it be that manufactured housing has clung to the ideal of being unsubsidized housing at its own peril? Answer this question and I'll give you a prize."

Financial penance

There has been a notable shift toward more real estate financing for manufactured homes, as fewer homes are sited in parks and more use permanent foundations. Still, the trend is a slow-moving one. Though little better than one-third of manufactured homes were titled as real property in 2003, that's up significantly from 10 percent as recently as 1995. There are also significant regional differences. In the Midwest, the rate was slightly higher at 42 percent, and some district states are higher still.

Brunner from the Minnesota Manufactured Housing Association estimated that 85 percent of new manufactured homes in that state are purchased with a real estate loan. Evans from Centennial Homes said he believes South Dakota's rate of real estate financing is closer to 80 percent, up from basically zero a decade ago. "Ten years ago, no banks would do mortgage loans," Evans said.

(There is some evidence suggesting that government data tracking might only be catching up to this trend because in the past little information has typically been collected on the financial activity and trends related to manufactured housing. For starters, relatively few of the lending institutions that specialize in manufactured home loans are required to report activity under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, in part because reporting is only required of lenders in urban regions, and many manufactured homes are sold in rural areas. Even for these urban lenders, HMDA only started explicitly tracking manufactured home mortgages last year.)

Buyers of manufactured housing also appear to be paying for past sins in the industry. For a prime rate mortgage "your (interest) rate's going to be a quarter point higher" if you buy a manufactured home rather than a site-built home, regardless of credit history or income, said Evans, from Centennial. Even among upper-income buyers, 28 percent of real estate loans for manufactured homes were subprime in 2004, according to a 2004 report on lending activity by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

Neither does the industry want to do away completely with chattel loans, at least not yet, in part because it's the only means of financing available for some buyers. Conventional mortgages, for example, require an appraisal of three "like sales" within a five- or 10-mile radius to double check loan-to-value ratios. In rural South Dakota, where homes of any sort might be sparse, "that's not happening," said Evans. As a result, "your only option is a chattel loan."

Nowhere but up?

The industry has been talking about a turnaround for several years. In 2003, not many believed things could get much worse, then placements fell another 10 percent. Still, some point to signs of better fundamentals for the industry to finally start being optimistic this year.

"I think we'll start to see a rebound," said Brunner, from the Minnesota state association. Over the past half-decade, "we lost a lot of financing, especially on the chattel side," but he added that lenders are again starting to kick the industry's tires. "They're starting to come back, but with higher (loan) standards."

Things are looking more positive in Red Lake Falls, Minn., home of Homark Homes, an employee-owned firm that builds about 130 homes a year ranging in price from $30,000 to $99,000.

"We had a good year last year and we're hoping for a good year this year," said John Halfa, Homark's controller. Production at the employee-owned firm was up about 10 percent last year. So far this year, the company is ahead of last year's pace, which he measured in part by the length of the annual companywide winter furlough of the past few years. "We're two weeks ahead of last year."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.