Despite the large role private businesses play in the U.S. economy, our understanding of the American self-employed entrepreneur is largely informed by stories: Did a financial windfall unlock the ability to pursue a dream? Are they trading financial gains for the flexibility of being their own boss? Do they tend to make more or less than other workers, and at what risk?

Most insights to date are the product of surveys, which are subject to shortcomings of sample size, self-selection, and bias in responses. In new research, however, Minneapolis Fed consultants Anmol Bhandari and Ellen McGrattan of the University of Minnesota draw a portrait of self-employed Americans from an extensive administrative dataset of IRS and Social Security records (Minneapolis Fed Staff Report 670, “On the Nature of Entrepreneurship,” with Tobey Kass, Thomas May, and Evan Schulz). Rather than try to pin down the “typical entrepreneur,” they follow “the typical dollar earned in self-employment”—and then analyze what these tax and employment data tell us about the people who earned those dollars.

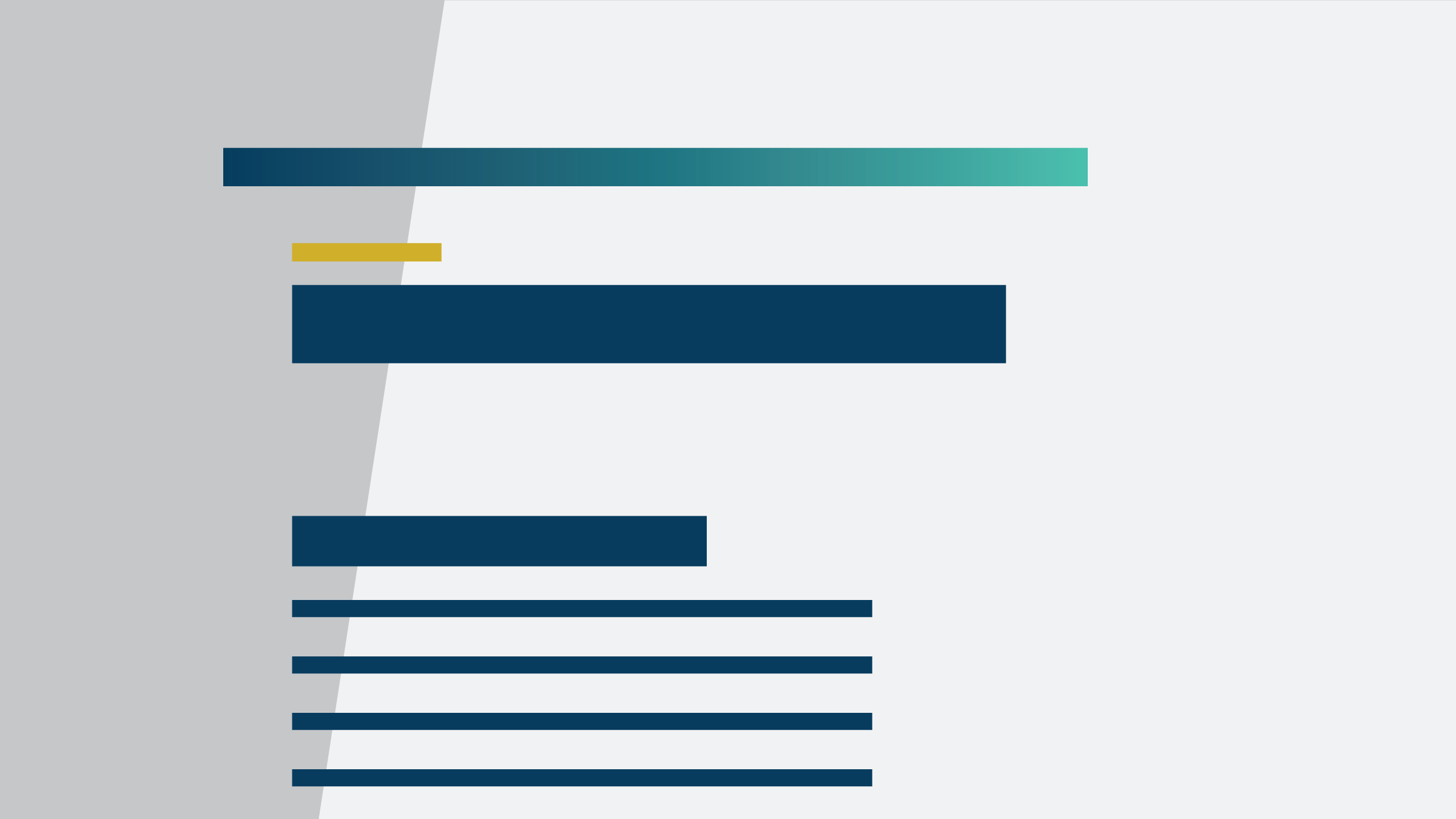

The data (which the authors make publicly available) reveal that self-employed Americans make significantly more, on average, than those who work for a paycheck. Across the full sample of taxpayers between 2000 and 2015, workers classified by the economists as primarily self-employed had an average annual income of almost 60 percent more than “paid-employed” workers.1 The difference is in the trajectory of income over the life cycle. Using a balanced panel of self-employed and paid-employed workers, the economists trace the steeper expected income growth of workers who try self-employment during the sample period compared with those who do not (see figure).

While earnings for both groups are similar at age 25, by 55—a time of peak earnings, statistically—the average annual income for a worker who has tried self-employment is nearly twice as large ($134,000 versus $79,000 in 2012 dollars). The actual disparity is likely even larger, given the presumed underreporting of self-employment income to the IRS.

These findings of much higher average earnings cut against the notion that entrepreneurs are eking out a living on a labor of love or foregoing money for the flexibility of working for oneself.

However, the average income of self-employed workers masks a high degree of inequality. The difference in income growth between the 90th and 10th percentiles of self-employed workers is 2.5 to 3 times larger (depending on age) than for paid-employed workers. Self-employed incomes are also more heavily skewed toward the top, with 80 percent of all self-employment income earned by those who make more than $100,000 per year.

Controlling for education, skills, and other factors, the majority of self-employed individuals earn less than comparable paid-employed peers, at least in terms of income reported to the IRS. While underreporting likely understates the income of most entrepreneurs in the data, it is clear that “the typical dollar in self-employment does not come from the typical self-employed individual,” the economists write.

Prior research has suggested that the risk of entrepreneurship appears greater than the expected reward—a so-called private equity puzzle. McGrattan, Bhandari, and co-authors use moments from their data to infer estimates of risk aversion that would rationalize the considerable income risks that entrepreneurs take on. Armed with the new, hard data, the economists find no puzzle here: Individuals would rationally take on the income risk, provided they are insured against the most adverse shocks.

The higher cyclical risks faced by entrepreneurs are especially evident in this dataset during the Great Recession (2007–2009). In 2008, self-employed incomes plunged 10 percent below their average in the years prior, while paid-employed incomes only declined modestly. The drop in self-employed incomes was concentrated in construction and real estate, sectors hit especially hard during that period. Despite this blow to average income, however, most entrepreneurs appear to ride out their choice to go it alone; the economists find no increase in exits from self-employment.

In contrast to some survey evidence warning of a decline in American dynamism, the IRS data show no decline in entry rates to self-employment or the share of entrepreneurs in the U.S. economy from 2000 to 2015. What enables these entrepreneurs to launch their ventures? Here the new research undermines a common perception that self-employment often requires a windfall or large stock of collateral. The economists find no positive relationship between self-employment and past housing wealth, financial asset income, or spousal income. Nor do business founders—the subset of entrepreneurs who can be associated with a specific business in the data—appear to be leaning heavily on bank loans or credit cards, based on an analysis of their business interest expenses.

Self-employed individuals do stand out in one important respect versus their paid-employed peers: talent and experience. Those who enter self-employment have higher past labor incomes than paid-employed individuals with otherwise similar characteristics. In contrast to survey-based research suggesting self-employment is a refuge for “misfits,” the administrative data show those who switch into self-employment are positively selected on past productivity.

The data provide other demographics to fill out the portrait of self-employed Americans between 2000 and 2015. Nearly three-quarters of entrepreneurs were men. They were more likely than paid-employed individuals to be married and to have children. Self-employed and paid-employed individuals were similarly likely to have a college degree.

There are as many entrepreneurial journeys as there are entrepreneurs—an important caveat to any effort to describe or understand the typical private business or self-employed person. However, the work from Bhandari, McGrattan, and co-authors establishes the value of hard data over the incomplete or misleading evidence we might take from surveys. The results lay a more solid base for economic models and policy analyses focused on the risks and incentives facing the many American businesspeople who strike out on their own.

Read the Minneapolis Fed staff report: On the Nature of Entrepreneurship

Endnotes

1 Income here includes wage income and self-employment income from sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations. It does not include interest, investment, or other types of income. The sample in this case includes observations for all individuals with occupational data who were ages 25 to 65, born between 1950 and 1975, and alive in 2015. Self-employed individuals have an absolute value of annual self-employment income of at least $5,000 and satisfy at least one of three additional criteria indicating self-employment.

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.