In the complex world of finance, most people see municipal bonds as a combination of Rip Van Winkle and Rodney Dangerfield: a little sleepy, and they get no respect.

At some levels, the reputation is deserved: When governments want new roads and buildings, they borrow money, build new roads and buildings, and pay the bills about as predictably as the setting sun. That’s kind of what makes the municipal bond market a bit boring: Governments don’t lose their job, skip town and stiff the bank on their debt.

Given municipal bonds’ relative safety compared with corporate stocks or bonds and their yield advantage over U.S. Treasuries, municipal bond issuers had gotten used to having access to affordable money when they needed it. Issue bonds, build the bridge, hit the snooze button until the next bridge.

But in mid-September, the crisis in the broader financial market gave the municipal bond sector a long, loud wake-up call, and the muni bond market has been anything but sleepy since. Governments accustomed to getting cheap financing were finding no takers, or they were having to swallow hard and pay much higher interest rates or be content to temporarily mothball projects and programs.

In early October, the state of California sought a $7 billion emergency loan from the U.S. Treasury because it could not find a buyer for routine short-term bonds used for cash-flow purposes. A state-run housing program in Wisconsin had to suspend lending about the same time because it could not get the underlying financing for the program.

But many might not be aware that, much like the broader financial system, the municipal bond market has been in a state of flux for some time, enduring bouts of both subtle and obvious volatility since the summer of 2007.

“To say that you’ve never seen anything like it almost sounds trite,” said Kreg Jones, senior vice president and managing director in public finance, D.A. Davidson & Co., a bond underwriter firm in Great Falls, Mont. He’s been with the company for 27 years, all in municipal finance. “I’ve never seen anything as deep and as broad. … It’s fair to say it’s scary.”

To put that in context, Jones was speaking in early September—before the financial market collapse at mid-month. What’s happened since in the bond market (and obviously the broader market) is truly unrivaled in recent times. But it didn’t happen overnight. Like many economic developments, it germinated much earlier, evolved sporadically and finally came to a more visible head.

The first signs of instability in the muni bond market became evident in August of last year when the subprime mortgage industry started to turn sour. Liquidity started to tighten, and interest rates rose slowly as cautious bond investors played harder-to-get while sizing up possible contagion effects. Then in early 2008, that tightness spread into full seizure for a growing type of variable-rate bond (called auction-rate) when muni bond insurers got exposed to the subprime crisis.

The auction-rate calamity was fast and furious. It affected only a small number of local and state governments directly, including a handful in the Ninth District, most of which were planning to finance health care facilities and student loans. But the municipal bond sector suffered shrapnel wounds from the flameout in this niche bond market because it turned the so-called enhancement market—insurance and other financial protections for bonds—on its head.

Despite the turmoil, much of the municipal bond sector returned to some measure of normalcy by the end of this summer. Though there were notable exceptions in student loan and health care bond markets, sources said deals were otherwise getting done. Some issuers had to accept higher interest rates, but the turmoil wasn’t stopping the business of government. Sewers and schools were getting built, governments were selling and investors were buying. Back to sleep, Rip.

And then the September crisis in financial markets hit like a howitzer, shutting off liquidity and seizing the municipal bond market. As of mid-October, by most accounts, the bond market was still reeling.

Broadly speaking, the September shock appears to have simply accelerated what was already evolving in financial markets (albeit more slowly and methodically): a flight to quality, where skittish bond investors ascend to safer ground. Generally, such a trend favors more-secure municipal bonds over the stock market.

But amid the recent financial chaos, flights to quality have rushed in different directions. Since mid-September, for example, investors have been stampeding past municipal bonds and piling into ultra-safe U.S. Treasuries. Muni bonds needing financing have been either paying higher interest rates or—particularly for large issues—getting shelved altogether.

What lies beyond the current commotion for the muni bond market is hard to know because it is currently traversing uncharted territory. The flight to quality should ultimately benefit municipal bond issuers, but not all issuers are created equal. Credit spreads—the interest rate differential between high- and low-rated bond issuers—are widening, and many expect that trend to hold. If it does, the ability of local and state governments to borrow affordably in the future will depend more than ever on the credit worthiness of issuers and their projects.

Muni bonds 101

When local and state governments need to borrow money for capital projects and a host of other priorities, they issue municipal bonds, the umbrella term for debt securities from nonfederal governments and any related authorities.

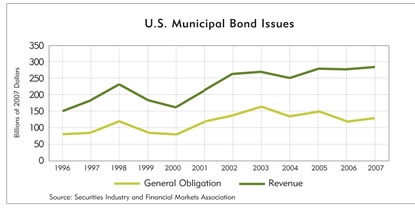

It might sound like a niche financial market, but it’s serious money. Nationwide, almost $2.7 trillion in outstanding municipal bonds is in the piggybanks of investors around the world—up from $1.4 billion in 1998, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). Municipal bond issuance reached a record $429 billion in 2007, 11 percent higher than in 2006.

Getting a handle on the municipal bond trends, at least outside of obvious shocks, can be difficult because there are many unique, interacting elements (many of which are defined and discussed either later in this article or in the sidebars: “Auction-rate fireworks” and “A question of credit”).

For example, thousands of entities are authorized to issue municipal bonds in the Ninth District alone, representing multiple levels of government (state, county, city, school district and others). These entities can issue different kinds of bonds (general obligation, revenue) for different needs or projects (schools, hospitals, housing, infrastructure, student loans) using different interest rate structures (fixed, variable) and varying maturities (months to 30 years) that require different levels of enhancement (insurance, letters of credit) depending on issuers’ individual credit rating (if they have one, which isn’t required to issue bonds), all of which help to determine a bond’s coupon (or interest) rate. Getting sleepy yet?

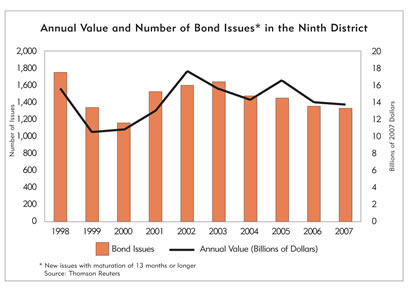

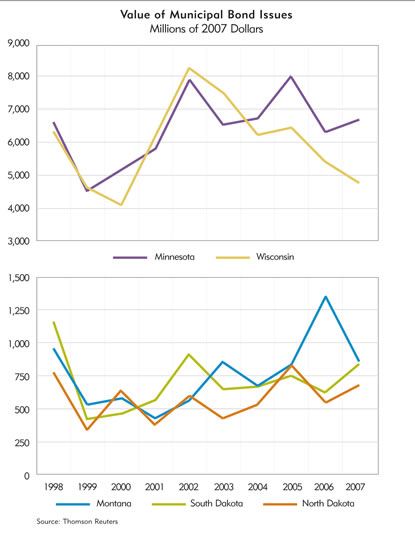

Since 1998, local and state governments in Ninth District states have issued between $10 billion and $18 billion annually in municipal bonds (inflation-adjusted), according to data on so-called new issues from Thomson Reuters, a financial services information firm. That includes 2008; through the first eight months, district states had already exceeded $10 billion. Among five district states, annual municipal bonding has zigzagged a fair amount over the past decade. (See charts below.) All of Wisconsin was included for this analysis; Michigan was excluded because the Upper Peninsula has a very small share of annual municipal bonding in that state.)

Each district state is unique in terms of its appetite for debt and the end use of bond proceeds. In South Dakota, for example, 37 percent of all bond proceeds issued in the past decade have been used to provide low-cost financing for single-family housing—easily the highest rate among district states for that particular use. Forty percent of bond proceeds in Wisconsin go for the generic designation of public improvement, which includes such varied things as road construction and general obligation debt used to close public pension shortfalls.

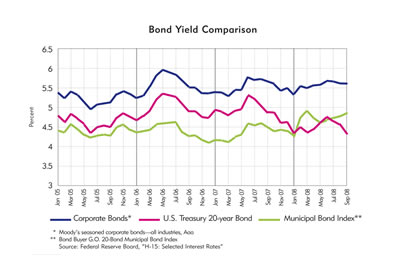

Municipal debt tends to be priced pretty cheaply because investors are happy to exchange the investment safety of a government payor for modest but predictable returns (typically 3 percent to 6 percent, tax-free, depending on the bond type and maturation). In this respect, muni bonds have something of a sterling reputation: not as safe as U.S. Treasury bonds—the gold standard—but much safer than corporate bonds, and that risk is reflected in the investment yield of each. (See chart below; note that nominal yields for U.S. Treasury bonds are typically higher, with recent exceptions, than those of long-term muni bonds. But Treasuries are subject to federal income tax, and most muni bonds are exempt from all income taxes. After factoring for tax effects, the yield of Treasury bonds is typically lower than the yields of municipal bonds.)

To retain that affordable financing, the municipal bond market has to remain a secure place for investors to park money. That was a virtual guarantee until late summer of last year, when the municipal bond market was shaken from its slumber to find that it faced indirect risks related to the subprime mortgage situation that was just starting to reveal itself.

The subprime sandwich

As the subprime contagion spread, more players in the interconnected world of global finance became infected. One of those sectors was bond insurance, which government issuers buy to enhance their credit rating.

Investors see bond insurance as a seal of safety and approval, because the insurer—by definition, historically triple-A rated in terms of risk—guarantees interest and principal payments even if the government issuer defaults. So bond insurance earns a government issuer a better credit rating than it could get on its own, and the cost is more than offset by the cheaper financing that results.

Bond insurance has been cheap, and “it added value to broader marketability” in terms of attracting more buyers, said Frank Hoadley, capital finance director for the state of Wisconsin. “It made life easier for (Wall) Street … (and as a result) the buy side spent significantly less time and money on analysis.”

Ultimately, the virtuous circle of bond insurance became a vicious one. Bond insurers are also referred to as monoline insurers because historically they only insured municipal and corporate bonds. But the sector saw opportunity in the subprime market and began insuring now-infamous “collateralized debt obligations”—subprime home mortgages as well as other asset-based debts (like car loans) that were bundled together and then resold as bonds.

When subprime mortgages started defaulting, so did CDOs, putting insurers on the hook for billions in payments to bond holders. Ambac, until recently the world’s second-largest bond insurer, suffered $1.7 billion in losses mostly related to CDOs in the first quarter of this year.

From there, it was a straight-ahead crash into the municipal bond market. Ambac was downgraded by Fitch Ratings in early 2008. Without the triple-A credit rating, bond insurance is largely wasted money, because investors are no longer willing to accept smaller returns if a bond’s financial safety net is suspect in any way. Later in the year, other major bond insurers (MBIA, CIFG Guaranty, Financial Security Assurance) would be downgraded or put on watch lists.

This crisis of confidence in bond insurance spawned two separate but connected reactions. The most immediate and intense came in so-called auction-rate securities, a growing, widely insured bond niche that collapsed in February. (See “Auction-rate fireworks: Ooh, aah, ouch”.)

The crisis in auction-rate bonds further intensified a growing spotlight on the broader credit enhancement market—third-party insurance and letters of credit that protect bond investors from loss. (See “A question of credit.”)

With fewer triple-A rated firms offering their gold seal of protection, sources said, costs for credit enhancement have gone up. As a result, lower-rated governments, which have more of a rationale to buy credit enhancement in the first place, faced higher borrowing costs regardless of their action: They could either buy higher-priced enhancement or eschew it and stand on their own (lower) credit rating.

That’s why credit spreads have been widening. The interest rate spread between triple-A and a low investment grade rating (Baa) widened from about 30 basis points in June of 2007 to about 120 basis points a year later, according to Dave MacGillivray, a principal with Springsted Inc., an investment advisory firm in St. Paul that counsels hundreds of city, county, school district and other government clients. On a 20-year, $10 million bond, those 90 extra basis points would add more than $1 million in interest costs over the life of the issue, MacGillivray said.

That credit spread potentially affects more than just a few outliers. Minnesota, for example, has a reputation for good governance. But according to a March report by Moody’s, more than 20 percent of the 390 cities, counties and school districts that are rated by Moody’s have a rating of Baa1 or lower.

How credit spreads directly affect these lower-rated local governments is not a black and white matter, however, because some have the ability to piggyback onto the state’s stellar Aaa rating to secure more affordable financing. Rising credit spreads have also renewed attention on muni bond ratings because the risk of municipal default—the fundamental concern of investors—is tiny, even for low-rated issuers (see “A question of credit” for more discussion).

Calm before the storm

Despite these challenges and controversies, the spring and summer months saw a return to relative normalcy for much of the bond market. Though some muni bond areas continued to struggle (particularly for student loans and health care facilities), sources said deals for routine government projects were getting done.

“I’m not seeing a lot of change in terms of municipalities having access to capital,” said Steve Apfelbacher, senior financial adviser and president of Ehlers Inc., in an interview during the second week of September. Ehlers is a financial adviser to government with offices in the Twin Cities, and one of the nation’s largest bond sales firms. “The typical Twin Cities community hasn’t been affected. … We’re not seeing (problems) on small issues.”

Ditto for Jones of D.A. Davidson in Montana, who said in early September, “We’re not seeing any constraint in getting things done at that local government level. … We’re having excellent placement rates.”

New municipal bond issues nationwide and in the Ninth District were little changed through the first eight months of this year, according to data from The Bond Buyer, an industry publication. Given a volatile stock market, highly rated borrowers were also seeing very competitive bond rates.

Who turned out the lights?

And then mid-September happened. During the week of Sept. 15, financial markets plunged with the news of the Lehman Bros. bankruptcy, the sale of Merrill Lynch to Bank of America, the bailout of AIG by the Federal Reserve and the eventual push later that week for a huge bailout package for the financial sector.

That week, everything changed in the municipal market, in part because of overall jitters, and also because Lehman, Merrill Lynch and AIG were major players in the bond market. One source said that liquidity in the bond market became “significantly constrained,” and market conditions from just a week earlier “are outdated.” Another source said some variable-rate muni bonds—whose short-term interest rates reset periodically—were moving from 2 percent to 10 percent, reminiscent of the auction-rate fiasco a half-year earlier.

Todd Hight, finance director for the South Dakota Housing Development Authority, the state’s largest bonding agency, said there was “not much to say; liquidity is drying up and there is no bond market.”

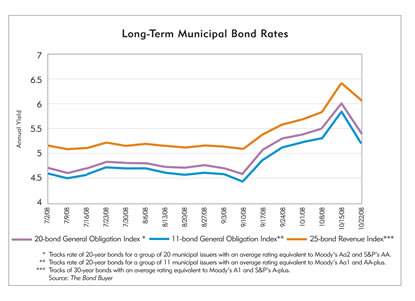

Interest rates rose across the board. According to indexes from The Bond Buyer, there was a jump of 30 to 40 basis points for long-term bonds between the first and third weeks of September, followed by a jump of similar magnitude by the first week of October (see chart below).

Interest rates rose even more for short-term bonds. Normally, there is a spread of up to several percentage points between short- and long-term bonds. But that started disappearing in September. MacGillivray, from Springsted, said that the rate between a 20-year bond and a one-week variable-rate bond was only about 75 basis points, give or take, and only 10 basis points separated a 20-year bond and an 18-month bond he had sold for a Midwestern city in early October.

Don Templeton, executive director of the South Dakota Health and Educational Facilities Authority (SDHEFA), agreed that the bond market “has really dried up. A bond issue can be sold, but at really high interest rates.” Templeton was at a national conference in late September, and he said that a lot of peer offices in other states “are putting bond issues on hold unless you’ve got a project you really have to get done.”

The final two weeks of September saw just $5.7 billion in new issues nationwide—a 60 percent drop compared with the same period a year earlier, according to The Bond Buyer. Media accounts typically stressed the complete lack of liquidity, as high-profile borrowers like the state of California and New York City—governments accustomed to issuing debt as a matter of course—suddenly found no buyers.

Liquidity has also tightened in the secondary market, where existing variable-rate bonds are resold. SDHEFA saw the interest rate on one variable-rate bond go from 1.05 percent to about 9 percent, according to Templeton. In the second week of October, it reset back down to 2.2 percent.

Deal or no deal

But some parts of the bond market have apparently remained fairly liquid. Smaller bond issues—up to $10 million or $15 million, according to sources—were still finding buyers, mostly retail investors attracted to the security of municipal bonds.

Jones, from D.A. Davidson, said his firm managed to complete a few small deals in the $10 million range. But this was merely the continuation of a trend under way even before the bond market crisis hit because retail investors were returning to basics, Jones said.

“People are having a terribly hard time digesting everything” that’s happening in financial markets, he said. That’s why there has been an uptick in retail investors going to what he called “vanilla” issues—bonds for local projects like a library that don’t involve a lot of high finance. “There’s nothing tricky there.”

There’s other evidence of that retail mentality in the district. For example, the “vast majority” of bonds issued by Minnesota counties are small, according to Joe Mathews from the Association of Minnesota Counties. In early October, Mathews was at a conference with county administrators from across the state. “I asked around to see if anyone was experiencing issues (in the bond market), and all replied that they really weren’t running into any problems.” Though some wondered if there would be trouble down the road, for the time being “counties seem to be operating as normal,” he said.

But it’s a different story for many large bond issuers. MacGillivray said that bond issues larger than $15 million or so were having difficulty selling because “institutional buyers are not participating.” For starters, institutional investors are consolidating—A.G. Edwards was bought by Wachovia last year, which was bought by Wells Fargo. That consolidation leaves only one buyer where there used to be three.

Equally important, in the current environment institutional investors have to be more careful with available capital; they are more reluctant to tie it up in bonds “because they might have liquidity needs elsewhere,” MacGillivray said. As a result, governments with large issues they know likely won’t sell “are sort of sitting on the sidelines watching to see what’s happening.”

Apfelbacher, from Ehlers, said in early October that the firm’s bond sale department was told by several investment firms that they weren’t in the buying mood. One firm, according to Apfelbacher, said that “unless they get orders (for munis), they will not bid on any issue. They do not want inventory.” Another said that “banks do not have money presently to buy bonds and until they do they will not be buying munis.”

For Jones, from Davidson, “larger issues have been extremely challenging, and we have delayed anything that does not absolutely have to come to market. … Right now, everyone is sitting on their wallet and happy to avoid any big mistakes.”

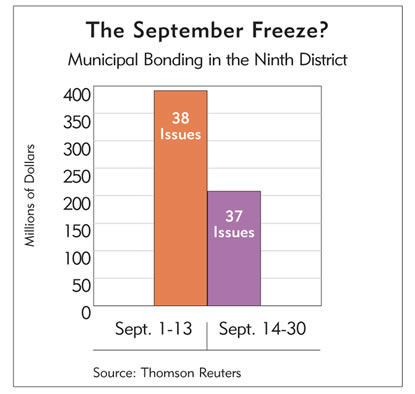

That liquidity scenario—tight for large issues, more liquid for smaller ones—can be seen in September activity. Despite the fact that the number of issues brought to market was virtually identical between (roughly) the first and second halves of September, the value of those issues dropped by 47 percent (see chart).

Bond vertigo

The bond market is likely to take a while before it resembles its old self, sources said. With so many issues deciding to wait out the market for lower rates, there is now a backlog waiting to come to market; when these bonds start seeking funds, the pent-up demand for funding will likely keep bond prices high as a glut of projects chases available money.

But at some point, most sources believed, the muni bond market will be an attractive place for investors. In late September and early October, investors were fleeing to U.S. Treasuries, whose short-term yields were nearing 0 percent. “At some point, they (investors) are going to get tired of getting 0 percent from Treasuries, and they’ll start going to munis,” said MacGillivray.

“This is structural. It’s not like (the reaction from) a bad jobs report. It’ll get worked out. There will be a functioning municipal market, but no one knows what time frame it will be,” said MacGillivray. The bailout package passed by Congress in early October would likely help, he added, but it was unlikely to unglue the bond markets. “It’s not a light-switch situation. It’s more like a light at the front end of a long, dark alley.”

Apfelbacher, from Ehlers, offered some historical context: Bond rates have risen significantly since hitting the low 4 percent range in December 2006. Still, prevailing long-term rates (nearing 5.5 percent in early October) were a fraction of the rates in 1982, when they topped 13 percent, and “we still issued bonds in 1982.”

By mid to late October, the muni bond market showed signs of loosening. The entire week of Oct. 20 saw very strong activity, for example. Large new issues and secondary markets finally started finding buyers as institutional investors began to return and bond rates dropped considerably. Traders, however, disagreed on whether the market had turned a corner or was seeing a short-lived burst, according to daily market updates from Municipal Market Advisors, an industry research firm. Bond activity the following week of Oct. 27 was more subdued, according to MMA.

Which way is up?

When the shaking stops and the dust settles on agitated financial markets, it’s uncertain what the “new normal” will look like in the municipal bond market. Most evidence suggests that the September haymaker that landed on the bond market simply accelerated the flight to quality that was already under way. In the short term, government borrowing will cost more; for those with less than stellar credit ratings, and those using more exotically structured bonds, interest rates will likely be higher still.

Longer term, one might anticipate subtle shifts that reflect the flight to safe havens, like a return to the safety of general obligation bonds, which come with the full faith and taxing authority of the issuing government. If repayments lag, the issuing government can make its taxpayers simply pony up the necessary money to repay bondholders.

Its counterpart is the revenue bond, which is repaid by nontax sources, most often revenue generated from the project being financed, like the rate hikes that result from a new sewer system. Revenue bonds are more popular and have grown faster in the past decade (see chart), in part because they don’t require direct taxpayer funding or approval. But in a world seeking safety, some types of revenue bonds could see rough water because their repayment streams can be less dependable. Prevailing rates on 30-year revenue bonds have soared from about 4.7 percent in January of this year to more than 6 percent, according to The Bond Buyer.

Speculative economic development by local communities was another example, according to MacGillivray. In the past, one could find investors for a retail development in a tax increment finance district even before construction began, so long as the project had a reasonable number of leases already in hand. Speaking about this matter in early September, he said investors aren’t interested “unless a lot of extra guarantees are involved,” which pushes so-called marketing costs up considerably, MacGillivray said. “Nobody’s taking construction risk. ... These days the building has to be under construction, and leases have to be in place.”

MacGillivray also said that growth-based infrastructure expansions might struggle to finance debt. In light of the housing slowdown, “if your new sewer is based on (payments from) a thousand new rooftops a year, … they’ll have some challenge.”

In the long term, sources said, no one really knows what to expect. “I think it’s just too early to tell what the long-term implications for the muni bond market will be,” said Templeton, from SDHEFA. “Wider credit spreads seem likely to be with us for a while, particularly for lower-quality credits.”

“For a while, things are going to be different,” said MacGillivray, in part because he and other sources believed the bond market was not yet done with surprises. “Nobody knows how this is going to play out. … There were big shocks to a market that doesn’t deal (often) with shocks.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.