With the recent churn in financial markets, many parts of the economy are being forced to re-evaluate their financial circumstances. In a similar vein, local governments are getting better acquainted with the fundamental notion of credit risk.

Over the past decade, there has been steady growth in so-called credit enhancement, an umbrella term for insurance, letters of credit or other financial protections that bond issuers wrap around an offering to make it more attractive to investors. Until recently, bond issuers gladly traded the added cost of enhancement for lower financing costs.

But turmoil in municipal bond markets—and more specifically among bond insurers and banks that provide credit enhancement—is convincing some issuers to forgo such third-party bond protections. It’s also leading some to question the fundamental credit risk of municipal bond issuers and the credit rating system that has historically been treated as gospel.

Are you in good hands?

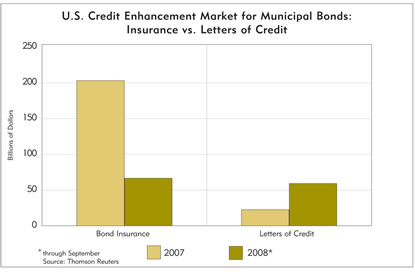

Until recently, insurance had been the dominant form of credit enhancement for municipal bonds, making up 90 percent of a $220 billion enhancement market in 2007, according to data from The Bond Buyer.

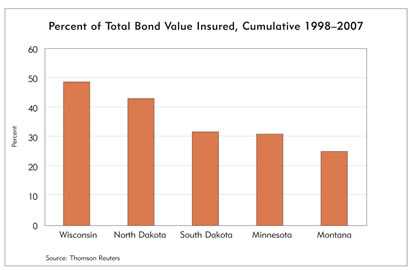

Municipal bond issuers in the Ninth District tend to use insurance less frequently (38 percent of bond value in 2007) than counterparts nationwide (46 percent), though there is considerable variation among individual states (see chart) and in any given year.

But recent trouble among bond insurers (see cover article) has shaken the enhancement market like a Christmas snow globe, creating a two-tiered market: downgraded firms that the market no longer trusts and untainted firms that are getting more business than they know what to do with, which has limited access to insurance and pushed prices up.

Last December, the Montana Facility Finance Authority was preparing a $130 million fixed-rate bond offering for a health care facility in a larger Montana city (unnamed here because financial negotiations are ongoing). The initial deal was ultimately postponed because of concerns about the bond insurer—Ambac, which was on downgrade watch lists at the time.

Fast-forward nine months, and by September, the medical facility had managed to finance $60 million in a private placement, but work continued on the remaining $70 million. One of the problems was finding affordable enhancement. “The cost has gone up for the borrower,” said Michelle Barstad, executive director of the Finance Authority. “The question is, can you find the underlying enhancement, and at what cost? … People are demanding exorbitant fees because there are fewer players.“

Several sources said bond insurance premiums have doubled or tripled in price—from 20 or 30 basis points of principal and interest to upward of 80 basis points. Not surprisingly, the proportion of insured bonds has plummeted; by year’s end, it will likely drop by more than half nationwide compared with 2007 (see chart).

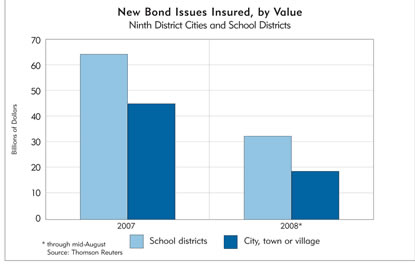

Use of bond insurance in district states has also fallen this year, to just 27 percent through mid-August. Historically, smaller, lower-rated issuers like cities and school districts have been persistent users of bond insurance. But their use of bond insurance has dropped dramatically as well (see chart).

Many bond issuers seeking enhancement have switched to letters of credit. Issued by banks, letters of credit are functionally similar to insurance in terms of offering financial protection. But LOCs also offer a liquidity guarantee; banks are obligated to buy the debt if there are no other buyers. From 2004 to 2007, the LOC market hovered around $20 billion to $25 billion. Thanks to the auction-rate implosion, it jumped to more than $57 billion through August of this year.

What’s ironic is that the bond market shifted away from insurance because of concerns over the financial stability of bond insurers, only to lean more heavily on guarantees from a banking industry that was also hoeing a rough patch for much of the year, and fell into a free-fall in mid-September with the financial crisis. Before that crisis hit, one Wisconsin official involved in state bonding pondered, “I sit here and wonder, could what happened in the municipal insurance market replicate itself in banking?”

Well, yes, it seems. According to The Bond Buyer, three of the five largest LOC issuers through the first half of 2008—Bank of America, Dexia Group and Wachovia—either were experiencing solvency problems or otherwise had significant exposure to subprime markets.

And as has occurred among bond insurers, a two-tiered LOC market appears to be developing, where untainted banks get even more business. Kreg Jones, from D.A. Davidson & Co. in Great Falls, Mont., said that many LOCs were coming from major banks such as Wells Fargo, US Bank and Compass “that have not had the same exposure as other banks … to the subprime debacle. You see that in the way they trade.”

LOC prices are also rising. In early September, Jones said a letter of credit typically commanded a fee of 75 to 125 basis points, but added he is “seeing some upward pressure,” with LOCs recently priced as high as 150 basis points.

What’s my real score?

With or without credit enhancement, the price of borrowing has gone up for lower-rated municipal bond issuers, and will likely remain higher even after the current financial crisis subsides because investors are now paying more attention to underlying credit ratings.

In turn, this has created some backlash against the three-headed credit rating system cumulatively generated by Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings. Each rating agency maintains credit ratings on thousands of municipal bond issuers (as well as corporations and other entities that either issue bonds or seek credit). The market has long accepted these credit ratings as a given. But over the past year, the reputations of the credit agencies themselves have been badly damaged because of their failure to identify huge credit problems in subprime mortgages and other markets.

Each of the three ratings firms uses a relatively similar scale, generally running from triple-A to C, with multiple grades in between. These scales are used for both corporate and municipal ratings. However, municipal issuers are rated by their fiscal health relative to other municipal issuers, while corporate ratings look at an individual firm’s unique risk of default and default loss.

The methodological difference sounds harmless—and indeed, it might be. But municipal and corporate bond issuers with a similarly low rating are dramatically different credit risks because governments rarely default on their bonds.

In an April report on the municipal bond market, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association stated that “the actual risk of default and loss of most municipal issuers is nearly zero.” Officially, it pegged the default rate on municipal bonds at 0.06 percent, a rate five times lower than corporate bonds. Municipal Market Advisors, an industry consulting firm, estimated earlier this year that triple-A rated corporate bonds had a default rate up to 10 times that of (lower-rated) single-A rated municipal bonds.

The rating agencies themselves have acknowledged the disparity in risk between municipal and corporate bonds. In testimony to a House subcommittee in March, a Moody’s official said that if municipal issuers were rated alongside corporations, municipal issuers would consistently be in the top two ratings (Aaa, Aa). An early 2007 report by Fitch Ratings stated that most municipal bonds had “consistently lower default rates and higher recovery rates than similarly rated corporate and structured finance debt.”

Because of a seeming double standard in bond ratings, some argue that municipal issuers—particularly low-rated ones—are getting strong-armed or hoodwinked by the existing rating system into either paying artificially higher interest rates or purchasing credit enhancement to buy down those rates.

That’s difficult to prove. The existing rating system has been around for decades; markets have become accustomed to it, defenders insist, and they price debt accordingly. There is sophisticated expertise on both buy and sell sides of the market, as well as generally good liquidity, which helps markets find equilibrium. If bond rates were systemically and artificially high, both issuers and investors would likely be able to spot that and act accordingly, which also would bid prices down.

Steve Apfelbacher, president of Ehlers Inc., a public finance advising firm in St. Paul, believes the market has a good grasp of municipal bond risk, despite any rating-scale nuances. “When you look at the rate difference between A (rated) and triple-A, it isn’t a whole lot.”

As such, ratcheting up all municipal credit ratings on paper might do nothing for the interest rates government pays on its debt.

But this is not a black-and-white matter either. Both the buy and sell sides have relied heavily on rating agencies to properly gauge risk. Given their implicit or explicit role in the chaos of financial markets over the past 18 months, both the general competence of rating agencies and the accuracy of their ratings have come into question. It’s a bit like finding circumstantial evidence that there are 13 inches to a foot.

Yet despite an erosion of confidence in all three major ratings agencies, “the market has never been more reliant on them,” said Jones, from D.A. Davidson. “I’m not sure I understand it; I’m not sure the market understands it either. … I’m a little surprised that there hasn’t been a bigger uproar (from municipal issuers). But prior to the crisis striking, there wasn’t really any cry or hue that the ratings have to change.”

Nonetheless, both Moody’s and Fitch Ratings have pledged to move to a so-called global scale, which will base muni bond ratings on default risk. This is expected to boost ratings by an average of one to two grades for issuers with room to move up. In October, however, both agencies delayed the move because of the existing tumult in financial markets.

Once (or if) this change is implemented, what ultimately happens to muni bond rates is guesswork. A preliminary estimate in September by two of the leading municipal bond underwriters in Wisconsin concluded that lower-rated credits might see lower interest rates for future issues, which they estimated between 4 and 10 basis points.

Apfelbacher agreed that a new rating scale would likely have a very modest effect—maybe a few basis points. “It’s not a lot, but it’s something.”

Return to: The bonds of debt

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.