In the investment world, municipal bonds are often described as plain vanilla, for their simplicity.

Over the past decade, however, financial markets have developed sophisticated variable-rate products that delivered cheap financing for municipal bond issuers. Thanks to recent volatility in financial markets, two of those products—so-called auction-rate securities (ARS) and variable-rate demand obligations (VRDO)—now have their own ice-cream name: rocky road.

Both types of bonds are floating-rate, tax-exempt bonds whose rates reset periodically (usually weekly or monthly, depending on the bond). This design allows the borrower to issue long-term debt at very attractive, short-term interest rates because the bond is repeatedly resold in secondary markets, giving investors high liquidity. In essence, these bonds were advertised as money market funds with better returns.

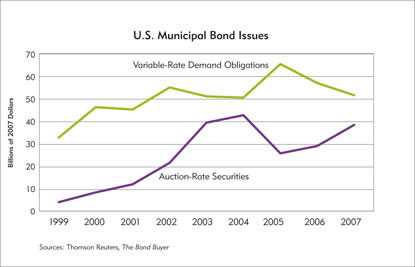

From virtually zero in the mid-1990s, both ARS and VRDO markets have grown considerably (see chart). In 2007, together they captured better than 20 percent of the municipal bond market, according to data from The Bond Buyer.

Sources said these bonds worked efficiently for both buyer and seller, and low interest rates have saved government issuers millions—indeed, likely billions—since their introduction.

In 2003, for example, the state of Wisconsin issued about $950 million in auction-rate bonds to help close a yawning liability gap in the state’s pension fund. For the first four years, state officials had nothing to worry about. “The bonds performed beyond our expectations,” in terms of prevailing reset rates, said Frank Hoadley, capital finance director for the state of Wisconsin. “It was great.”

When subprime mortgage problems first appeared in August 2007, bond investors became more cautious and liquidity started to tighten (see “The bonds of debt” for more details).” Hoadley’s office saw “a small tremor in August,” when resets on the state’s auction-rate bonds started trading in a range “with a little more amplitude” in relation to common benchmarks—a trend that continued through the end of the year, he said.

Auction-rate bonds are typically insured. So when Ambac, a major bond insurer, was downgraded by Fitch Ratings in January for its exposure to the subprime home loan debacle, the auction-rate market started to lose its footing because financial guarantees on this government debt were looking shaky.

Then “on February 12 or 13—pick your day—the bottom fell out,” said Hoadley. With doubts about bond insurers, major bond dealers, including Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and UBS, decided to stop supporting auctions. In the past, bond dealers were buyers of last resort. But faced with liquidity problems of their own, and seeing yet another volatile market in front of them, they sat on their collective hands. At that point, Hoadley said, “the whole idea of a correct market price was pretty screwy. It was a wild ride.”

Subsequent auctions did one of two things, both of them bad for government issuers: Buyers fled, and remaining bidders demanded much higher interest rates. Or auctions failed altogether—meaning there were no buyers, period. And because these auction bonds are marketed for their liquidity, a failure triggers the max (or penalty) rate that can range as high as 15 percent, even 20 percent. Issuers are forced to pay these higher rates until new, lower-bid auctions clear or the issuer redeems the bond.

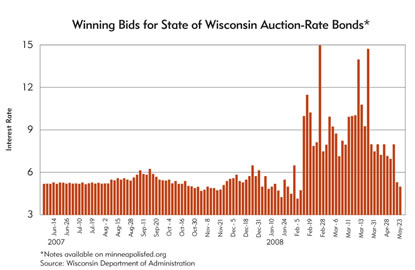

In Wisconsin’s case, the bond came in nine different “tranches,” or slices. Though there were no auction failures for any tranches, all but one reached interest rates of at least 10 percent, and three hit at least 14 percent (see chart). The state managed to get out from underneath these bonds by June. But the collateral damage had been done. During that brief window from mid-February to early June, the state paid an extra $10 million in higher interest charges, $5 million in additional finance charges and additional millions when beneficial swap arrangements had to be terminated.

The kicker is that the state had hedged every penny of its auction-rate bonds—meaning that it made other secondary investments that protected it from large interest rate swings. But the hedges were based on the assumption that auction rates would approximate shifts in the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), the rate banks charge each other for short-term loans and a common benchmark for floating-rate securities. “That’s where we got hurt. Auction rates were indifferent to LIBOR,” Hoadley said, and the much higher rates rendered the hedge moot.

The bonds that tie

Fallout from the auction-rate implosion appears fairly limited in the district. But where it hit, it hit hard.

Outside of Wisconsin pension obligation bonds, most of the exposure appears to be concentrated in programs that finance health care facilities and student loans, which pose little direct threat to taxpayers; the issuer is either a public agency that then lends proceeds to eligible private firms (like a hospital) that bear the financial risk or a nonprofit entity authorized to issue bonds and handle the distribution of proceeds.

That’s a cold salve for many private firms—particularly in health care—that financed programs or capital projects using municipally issued ARS or VRDO debt and are now dealing with the consequences. A South Dakota official, for example, said two hospitals financed by state bonding “have experienced some problems, with some interest rates going really high.”

They aren’t alone. At the beginning of this year, the Wisconsin Health and Education Facilities Authority had 32 auction- or variable-rate bond issues worth $2 billion with 19 different borrowers in its portfolio, according to Larry Nines, WHEFA executive director. Those involved are among the largest and strongest health care organizations in the state, and they chose this type of financing because they could; small or financially shaky health care firms can’t get such financing, Nines said.

By the spring of 2008, each of these WHEFA bonds saw interest rates rise from an average of about 3.5 percent to at least 6 percent, and some went as high as 14 percent to 16 percent, Nines said. By the end of August, about three-fourths of these bonds had been restructured.

Even temporary rate spikes hurt. Each percentage point increase on $1 million of debt adds $10,000 a year in extra interest charges, according to Nines. If a health care firm borrows $50 million for a new hospital, a rate hike from 3.5 percent to 6.5 percent adds $125,000 a month in financing costs.

Frozen bond-bonds

Probably no one in the district has been put through the auction-rate wringer like the Montana Higher Education Student Assistance Corp.

Created in 1983 to provide a secondary market for federal student loans and help finance college for Montana students, MHESAC has seen annual bonding levels over the years creep from about $35 million to upward of $250 million for a few years this decade when low interest rates created a wave of student loan consolidations.

MHESAC started out issuing fixed-rate bonds, but found over time that floating-rate bonds made more sense for a variety of business reasons, none more important than the fact that they were a cheaper way to finance student loans, as well as a better asset-liability match for these kinds of loans, according to Jim Stipcich, chief executive officer and president of the Student Assistance Foundation (SAF), which is MHESAC’s business manager. Today, MHESAC has $1.9 billion in outstanding bonds, $1.2 billion of it in auction-rate securities.

Like others, Stipcich started seeing liquidity problems in August 2007. There were fewer buyers, which meant interest rates had to go up to attract investors, pushing interest rates from 3 or 4 percent to 5 or 6 percent, he said. Then in February, auctions for student loan bonds—MHESAC’s and similar loan programs elsewhere—began failing altogether, which automatically triggered the max rate. One of MHESAC’s auction bonds reset at 10 percent for three weeks.

“You pay the rate and look everywhere you can” for interested investors, said Stipcich. “I was talking to everyone.”

As of early September, MHESAC had not been able to restructure any of the bonds because “liquidity is extremely scarce.” He added that at the time, “the urgency (to restructure) is a hair less” because rates had drifted back down.

But MHESAC has taken a hit financially. According to a June 2008 report by the Legislative Fiscal Division of the State of Montana, the organization experienced an unbudgeted increase of $14 million related to higher interest rates just in those few months, causing MHESAC to post its first-ever operating loss this past fiscal year.

There are other consequences for Montana citizens as well. For example, MHESAC has had to pull out of the consolidation loan business, according to Stipcich. In turn, SAF downsized by almost 70 employees because MHESAC and several other of SAF’s student loan clients “are not making as many loans,” he said. Primary federal student loans have not yet been affected—though future financing is a bit more up in the air.

Stoned soup

If there’s any doubt regarding the market’s auction-rate indigestion, consider the recent trend. As of early October, not a single new auction-rate issue has been sold in 2008—this after the market gobbled up $39 billion worth last year alone, according to The Bond Buyer.

Most of that bonding business (including many conversions out of auction-rate bonds) has been transferred to VRDOs, a market that grew from $52 billion in 2007 to $95 billion through just the first nine months of this year. VRDOs typically come with a letter of credit—in essence, a promise from a bank to be a financial backstop should problems arise, and the market viewed this as a good lateral move away from auction-rate bonds that were insured by firms with significant exposure to the subprime housing problems.

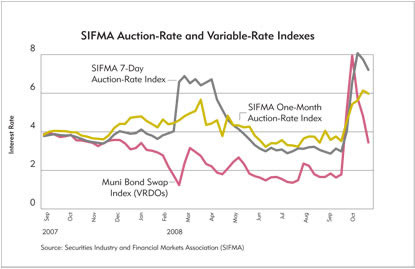

But the mid-September chaos in financial markets convinced holders of VRDOs to hit the exits, sending financing rates up for those as well. Stipcich said that borrowing costs on MHESAC’s lone “solidly performing” VRDO went from 1.8 percent to 5.6 percent by about mid-month. “Liquidity has been extremely difficult to find.” They were hardly alone, as rates for both VRDOs and ARSs jumped in September (see chart ).

Stipcich has pointed out that MHESAC’s bond problems were not due to the underlying business model, or to delinquent student loans. Rather, they were yet another contagion effect of the subprime mortgage crisis, as markets were getting skittish over similar kinds of securitized assets, like student loans.

“No one anticipated the depth of subprime problems,” Stipcich said. “Could anybody have predicted this? Nobody did, and we did business with the best minds in the world.”

The Montana Facility Finance Authority has experienced difficulties with VRDO markets. It manages one bond pool that resets weekly. It went from 5.25 percent to 10 percent in a span of three weeks during September, according to executive director Michelle Barstad.

Higher borrowing costs were not the result of missed payments or bad credit ratings. Simply, some bond issuers have taken more of the brunt from the subprime fallout. Access to credit markets, Barstad said, “is becoming more restrictive and expensive for entities that had nothing, nothing, nothing to do with subprime.”

Return to: The bonds of debt

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.