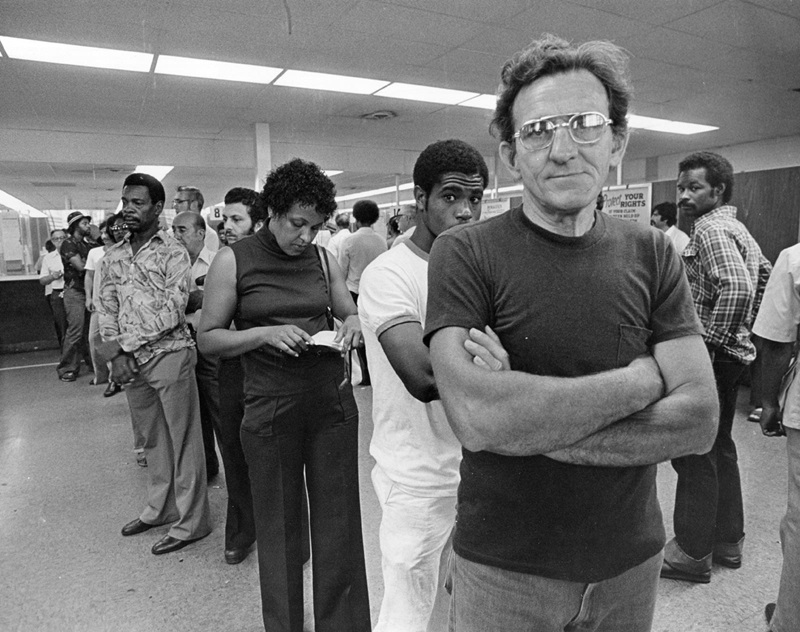

Understanding the condition of the U.S. labor market requires more information than the unemployment rate alone. A labor market where unemployment spells last a few weeks is likely very different from one where job seekers take half a year or more to find work, but both may have identical unemployment rates. One key indicator is the long-term unemployment rate, which is commonly defined as the share of the labor force that has been out of a job and seeking work for 27 weeks—about six months—or more.

The long-term unemployment rate quantifies a particularly severe and possibly harmful type of unemployment. Knowing the extent of such unemployment adds insight into how workers are faring, and it may contain information about how dynamic the economy is—when change is not only possible, but perhaps frequent and hopefully efficient.

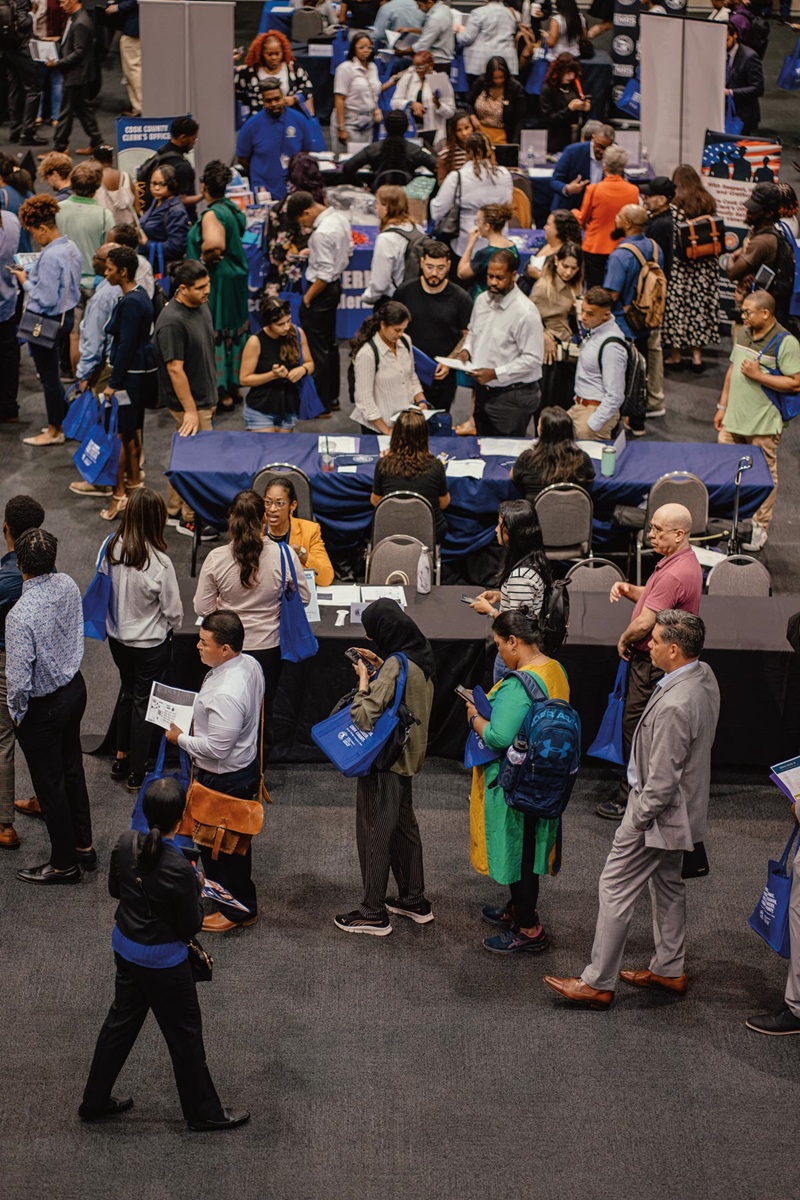

Long-term unemployed workers are also a potential resource for economic growth. In an aging economy, growth depends in part on finding new workers. Those who are long-term unemployed are a ready source of such workers, since they are already actively seeking employment. An economy seeking growth cannot afford to overlook them.

Long-term unemployment in the U.S. experienced an unprecedented recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic, but there are indications that it has started to rise again. In this article, we examine the recent swings in long-term unemployment, its historical trends, and ideas about where it may be heading in the near future.

Where are we today? The COVID surge in long-term unemployment has faded

In the first week of March 2020, 208,000 people filed for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, a convenient weekly measure of overall unemployment. This was a historically low number, especially in light of the long, slow recovery from the Great Recession, when as many as 665,000 people became unemployed in a single week in 2009. By the end of March 2020, COVID took hold in the United States and 6 million people claimed unemployment.

Economists and policymakers voiced concerns that a shock of this size would create lasting and painful long-term unemployment. They had at least three clear reasons to worry.

One related to the size of the COVID-19 recession. The shock in 2020 generated an enormous increase in the number of unemployed workers, and unemployment is the first link in a sequence that can develop into long-term unemployment (see “The journey to long-term unemployment”). From April to May 2020, the unemployment rate shot from 4.4 percent to almost 15 percent, the fastest change ever recorded and the highest level since the Great Depression. Millions of newly unemployed workers, especially those with less formal education, low wages, or a history of unemployment spells, were suddenly at risk of becoming long-term unemployed (Machin and Manning 1999; Mueller and Spinnewijn 2024).

A second concern came from the fact that no one knew how long COVID’s economic effects would last. This likely slowed job finding, narrowing the path back to employment for the millions of newly unemployed workers. The number of vacant jobs per unemployed worker and the monthly probability that an unemployed worker found a job fell by about one-third in the first months of the pandemic (Mongey and Horwich 2024). As long as these hiring conditions held, the unusually large pool of unemployed workers would be more likely to move toward long-term unemployment.

Finally, unemployment is, to some extent, self-perpetuating. Job searchers lose steam (Zuchuat et al. 2023), skills deteriorate (Cohen et al. 2025), and firms are less likely to hire applicants who have been unemployed for a longer duration (Eriksson and Rooth 2014). With so much of the economy shut down during COVID and with income supports expanding, millions of newly unemployed workers would miss out on their best opportunity to find a new job because they were unable or unwilling to search for one right away.

Consistent with these concerns, and with all previous U.S. recessions, long-term unemployment did rise rapidly after COVID. Figure 1 shows that the share of the labor force (everyone who either has a job or is looking for one) who had been out of work for six months or more rose to 2.6 percent in March 2021, representing 4.3 million people and more than triple its pre-pandemic level. Moreover, the experience of long-term unemployment was more widespread than traditional point-in-time measures suggest. In California, 14.5 percent of the labor force received UI for at least 27 weeks during the first year of COVID. Not all of them received it in a single spell, however, and so were not officially considered long-term unemployed (Bell et al. 2022).

The substantial rise in long-term unemployment in 2020 ultimately did not last. Even just one year after its peak in March 2021, the data show that initial fears about lasting changes to the structure of American unemployment did not materialize. Figure 1 shows that by mid-2022, the long-term unemployment rate had fallen back below 1 percent.

This recovery also holds for groups of workers who ordinarily have quite different labor market outcomes. No group of workers defined by age, education, race, or sex had appreciably different long-term unemployment rates in 2024 than they did in 2018, even though they had very different levels of long-term unemployment in both periods.

How did the U.S. avoid a prolonged period of elevated long-term unemployment? The most important factor was the speed of the COVID recovery. The unemployment rate fell almost as fast as it had risen and hit its 2019 low of 3.5 percent in July 2022. In fact, many macroeconomic relationships returned to normal within two years of COVID’s arrival, and the labor market was tighter in 2022 than in 2019. These extraordinary changes drew many workers out of unemployment before COVID and its consequences pushed them into long-term unemployment.

Yet as striking as the COVID recovery was, the pre-pandemic baseline to which the labor market returned is itself the product of substantial long-run changes. Instead of stability, this history of long-term unemployment in America shows large and highly consequential trends, and it is important to ask whether these will resume.

Where have we come from? A trend toward more long-term unemployment

The recession of the early 1980s was one of the worst economic crises since the Great Depression. Speaking to the Joint Economic Committee in December 1982, Martin Feldstein, then chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, stressed the “particularly severe” increase in the share of unemployed workers who were long-term unemployed, which had tripled to about 21 percent. “No one can contemplate such numbers,” he said, “without reflecting on the financial hardships that so many people have suffered.”

If he were speaking today, just two years since the post-COVID labor market recovery brought the long-term unemployment share back to its lowest level since the Great Recession, Feldstein would be even more concerned: 25.7 percent of unemployed workers in August 2025 were long-term unemployed.

The context for Feldstein’s original alarm and for today’s long-term unemployed workers accounting for 1 in 4 of all unemployed workers is shown in Figure 2. The path of long-term unemployment after selected recessions going back to 1960 highlights the trend toward higher long-term unemployment rates (Juhn et al. 2002). During expansionary periods in the 1950s and 1960s, less than one-quarter of one percent of the labor force had been unemployed for more than 26 weeks, and the share rarely exceeded 1 percent even during recessions.

The recessions during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s were worse. Figure 2 shows that not long after Feldstein’s testimony, 2.6 percent of the labor force was long-term unemployed, more than twice as high as in midcentury recessions. Cycles were also longer. The time between troughs in the long-term unemployment rate in the 1950s was about two years, but it rose to between five and 10 years after the ’70s. Recoveries, as measured by long-term unemployment, were also weaker. Figure 2 shows that long-term unemployment at the end of the recovery from the 1960 recession was 0.2 percent but it was more than twice as high—0.8 percent—at the end of the recovery from the 1981 recession.

The most severe long-term unemployment episode recorded in modern labor market data, also plotted in Figure 2, was the Great Recession. While the peak of the unemployment rate at 10 percent in October 2009 was not as high as in 1982, the peak of the long-term unemployment rate—4.5 percent in April 2010—was substantially higher. Moreover, the figure shows that long-term unemployment recovered very slowly, only returning to its pre-recession level after 10 years. Continuing the trend that began in the 1970s, this baseline level of long-term unemployment was itself relatively high, about 0.9 percent.

Economists have struggled to understand why the time that Americans spend in unemployment has grown over the last seven decades (Coibion et al. 2013).

Changes in the U.S. population and labor force, as profound as they are, appear not to be the explanation. For instance, the share of workers who do routine manual jobs (think midcentury manufacturing) has fallen from 60 to 40 percent since 1975 (Albanesi et al. 2013). Workers who lose routine jobs remain unemployed for about the same length of time as other workers, though, so this sectoral change probably cannot explain long-term unemployment trends. The flattening of women’s labor force participation in the 1990s made long-term unemployment more cyclical but did not change its trend (Albanesi 2025). Similarly, during the 2001 and 2008 recessions, “compositional changes in the unemployed account for virtually none of the observed rise in long-term unemployment,” according to a paper in the Journal of Labor Economics (Kroft et al. 2016).

Another idea is that changing labor market institutions are behind long-term unemployment trends. After all, programs like unemployment insurance, cash welfare, or disability insurance often do reduce employment (see Filges et al. 2018). The problem is that they have mostly become less generous since the 1990s (O’Leary et al. 2023), which would tend to reduce unemployment durations. One exception is disability insurance, which has grown significantly: Social Security data show that about 4.5 million more people receive it today than in 1980. But disability insurance is primarily linked to labor force exit (Autor et al. 2016; Maestas et. al. 2013), so it is not likely to be the reason why more people are long-term unemployed.

The best explanations, although far from complete, relate to how people search for jobs. Consider how the internet has made it easier to submit job applications. Between 1980 and the 2010s, the number of jobs to which a typical prime-age unemployed worker applied each month rose from 2.7 to 7 (Birinci et al. 2025). In an otherwise standard model of job search, this behavior can actually make unemployment durations go up. Firms have to sift through many more applications than they used to, which takes time that adds to the duration of workers’ unemployment. Submitting more applications also means that workers have a higher chance that a good job is about to come through, which may influence their decision to reject less-desirable offers and remain unemployed longer (Birinci et al. 2025).

Wage inequality can matter, too. If all jobs were identical and paid the same wage, then searching for a job would entail nothing more than waiting for an offer. With substantial wage inequality, however, workers may rationally pass up a lower-paying opportunity in the hope of getting a better-paying offer in the future. This would tend to mean that as wages became more unequal, especially at the top, unemployment spells would get longer. In fact, trends in wage inequality among comparable workers are positively correlated with unemployment durations between the 1970s and 2000s (Mukoyama and Şahin 2009).

Against this backdrop, the COVID recession appears as both an anomaly and a continuation of a trend. Long-term unemployment both rose and fell faster than in any other recession, but by 2022 it was back in line with recent history.

But the factors that are thought to influence long-term unemployment may be set to change. Artificial intelligence is already a part of job searches, for example, and major shifts to the safety net could affect support for unemployed workers and thus how long and hard they search.

Where are we going? The future of long-term unemployment in the U.S.

If the long-term unemployment rate’s rapid return to normal was a surprise, its recent uptick is a reminder: Recovery is not the same as stability.

Figure 2 shows that long-term unemployment tends to rise sharply during recessions and fall during recoveries. But over the past year, it hasn’t fallen; it has risen slightly. While the unemployment rate has held steady at around 4 percent since mid-2024, the long-term unemployment rate has ticked upward. This kind of rise is unusual during an expansion and is not part of the labor market’s typical recovery path. If it continues to climb, it could be an early sign of trouble.

One way to understand where long-term unemployment might be headed is to look at the structure of labor market flows. High churn—lots of firing, quitting, and hiring—would mean that unemployment spells rarely last very long, so increases in unemployment would not raise long-term unemployment by much. Low churn implies the opposite and is sometimes called low dynamism: Fewer unemployment spells begin, but the ones that do tend to last a long time. Therefore, if we know how these flows might evolve, we can predict how long-term unemployment might evolve too.

Pre-pandemic data on labor market flows suggest that a 1 percentage point change in unemployment would lead to about a 0.4 percentage point change in long-term unemployment one year later (Chodorow-Reich and Coglianese 2021). Applying this relationship to current forecasts, which predict an increase in unemployment from about 4.1 percent in early 2025 to 4.7 percent in 2026, suggests a rise in long-term unemployment of 0.24 percentage points. This is far from the typical peak during recent recessions but nevertheless means an increase of about 400,000 workers.

Specific labor flows may contain additional clues about future labor market trends. For example, in a tight labor market new jobs are relatively easy to find, so workers may feel comfortable quitting their job without having a new one lined up. Therefore, these “quits to nonemployment” tend to rise when the labor market is strong. In contrast, workers are worried about quitting in a weak labor market for fear that they will remain unemployed for a long time. In this scenario, quits to nonemployment fall. In fact, the rate of quits to nonemployment provides a better forecast of unemployment six months to a year later than measures like contemporaneous layoffs, even though layoffs predict short-term unemployment very well (Ellieroth and Michaud 2025).

All of these cyclical properties of quits to nonemployment make their sharp downturn in 2023 a worrying sign. Figure 3 plots the rate of quits to nonemployment among prime-age workers over the last three recessions. While these quits recovered especially quickly after COVID, the increase did not last. Quits to nonemployment have been falling for about two years, a pattern which was not observed in the recovery from the Great Recession or the 1981 recession. If workers have an accurate read of where hiring is headed, this may foreshadow rising long-term unemployment.

Another sign of change comes from recent labor market entrants. The average monthly unemployment rate for new college graduates in the first half of 2025 was 5.3 percent, up from 4.1 percent in the first half of 2022 and higher than the 4 percent rate for all workers. This mismatch could lead to longer unemployment spells for younger workers—both because they are having a harder time finding jobs now and because initial conditions matter. Workers who graduate into weak job markets experience earnings losses and higher unemployment for years (see Schwandt and von Wachter 2019; Kahn 2010; Oreopoulos et al. 2012). A generation that misses the first rung of their career ladder may carry those scars for decades.

But of course, long-term unemployment may not simply follow a predictable trend. For example, firms are increasingly using AI tools to perform the kinds of reasoning and communication tasks traditionally done by highly paid workers. What this means for long-term unemployment depends crucially on whether AI replaces these workers and creates new and possible long unemployment spells or allows them to do other productive tasks, preserving jobs and even raising wages (Freund and Mann 2025; Autor et. al. 2024). How these forces will affect aggregate trends is not yet known.

An array of specific policy shifts, too—such as new tariffs, changes to the tax code, cuts to safety net programs, tightening immigration enforcement, and federal downsizing—could shape long-term unemployment in ways that are not apparent in current data trends. Federal workers who lose jobs, for example, may struggle to find similar roles in the private sector (Sullivan 2025). New manufacturing positions may or may not emerge. Work incentives in safety-net programs may raise employment but could have unintended negative effects if they overlook barriers to employment (Gray et al. 2023; Gangopadhyaya and Karpman 2025).

Long-term unemployment is a particularly worrisome outcome, so its trends, fluctuations, and future are important to understand for policymakers and researchers alike. Recent increases may be small. But if history is a guide, these changes are worth watching closely.

With research assistance by Zoe Stein.

This article is featured in the Fall 2025 issue of For All, the magazine of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Abigail Wozniak is vice president and director of the Bank’s Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute.