The nation likes returning to rural America. Every week millions of radio listeners go back to Lake Wobegon to hear the news. They like the reassuring images of Main Street, where the women are strong, the men are good looking, and all the children are above average. Whether the aural art of Garrison Keillor or the printed frame of Norman Rockwell, the nation returns to these rural icons to confirm that all is well in America.

All is not well, however, if the nation looks past the icons to the real rural America. Some parts of the countryside are doing well, to be sure. Rural communities nestled in the Rockies of the Intermountain West, for example, are booming as newcomers flock to a scenic lifestyle. But a majority of rural places have not been swept along in the nation's long-running economic expansion. Many of the nation's farm communities, for instance, are struggling with the twin problems of a deep slump in the farm economy and a revolution in the way agriculture does business.

Put simply, many parts of rural America face a make or break period in the coming years. The challenges are immediate to thousands of rural communities scattered throughout the nation's countryside, but they are also important to the nation. Slightly more than a fifth of the nation's people live in rural America. Rural places make up 97 percent of our nation's space—places where we grow our food and where we go to play. Finally, rural America is home to more than 5,000 commercial banks, more than half the nation's total.

Rural America has always faced unique challenges, but the challenges ahead are of a different stripe, in part because the rural economy has moved far beyond agriculture. Moreover, a deep divide in the performance of the rural economy now makes it unlikely that a new tide will lift all rural boats. Against the backdrop of these rural changes, five challenges will be critical in shaping the rural economic outlook: tapping digital technology, encouraging entrepreneurs, leveraging the new agriculture, improving human capital and sustaining the rural environment.

How can these challenges be met in the new century? Historically, the public has responded to rural challenges mainly through agricultural policy. Yet given the breadth of rural America's needs, a much broader response will be required in the future. Thus, moving beyond agriculture to other rural policies promises to be a formidable transition for policymakers in the period ahead.

Big Changes in Rural America

Rural America has recently been a bubbling cauldron of change. Surging technology, expanding global trade, shifting demographics—these and a host of other forces have reached nearly every rural hamlet. The result is that rural America is hardly the same place that many Americans remember. Among the many changes, two are especially important to consider before policymakers give serious effort to expand rural America's horizons in the years ahead. The first is the diversity that now describes rural America. Rural no longer means farm—if it ever really did. Since agriculture remains the conduit for rural policy, policymakers face a new conundrum in thinking about rural America. The second is the deep divide in economic performance across rural America. Rural America today is a striking picture of the best and worst of times. That means it is hard to imagine a new tide that will lift all rural boats.

Beyond the farm

Rural America is highly diverse today, and far from the agrarian

monotype that Grant Wood once captured on canvas. A few definitions

are in order to describe this change. First, I will use the word

"rural" to refer to nonmetropolitan America—everything

beyond the nation's swelling metroplexes. Approximately 2,300

rural counties in the United States meet this definition, and

they contain nearly 54 million people, or 20 percent of the nation's

population. Viewed another way, the national landscape, with all

its treasures of natural resources, is overwhelmingly rural.

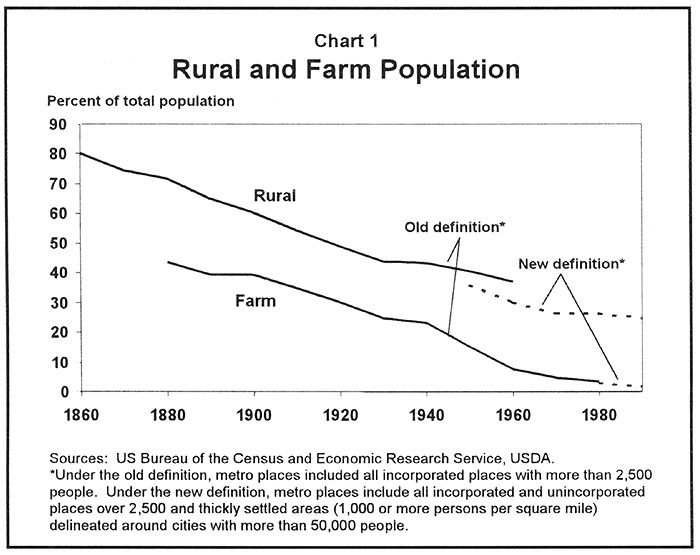

Over time, Americans have moved to the nation's cities, leaving farms and countryside behind. This trend is the natural course for nearly every nation that passes from agrarian, to industrial, to post-industrial. The United States is far along this path. When the Homestead Act was passed during the Civil War, fully 80 percent of the nation's people were in rural areas, and more than half on farms (Chart 1).

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census and Economic Research Service, USDA.

Under the old definition, metro places included all incorporated places with more than 2,500 people. Under the new definition, metro places include all incorporated and unincorporated places over 2,500 and thickly settled areas (1,000 or more persons per square mile) delineated around cities with more than 50,000 people.

Succeeding decades brought steady erosion in both the farm and rural population, but the pace was relatively slow. For instance, when World War II began the rural population still stood at 44 percent and the farm population at nearly a quarter. It was the huge scientific and economic leaps of the post-war period that produced a much faster farm exodus. By 1990, farm families were less than 2 percent of the nation's people-and much less than that if the definition of "farm" is limited to full-time farms. The rural population, while also considerably less, appears to have leveled off at between 20 and 25 percent of the population.

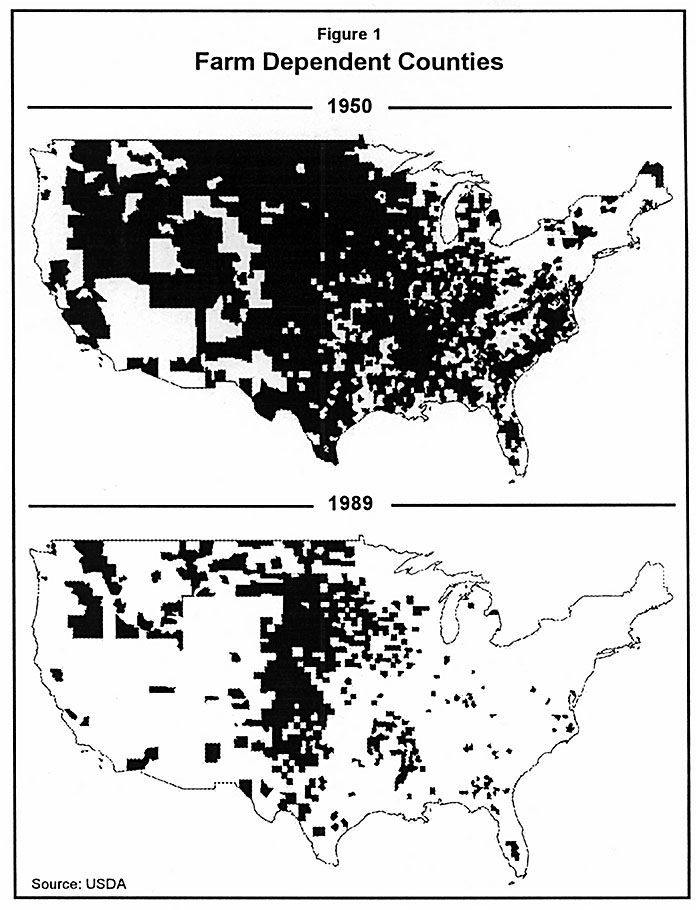

Another graphic barometer of how dramatically rural America has changed is the number of rural counties that count agriculture as their major source of income. Since 1950, the number of farm-dependent rural counties has plummeted from more than 2,000 to just 556 when the 1990s began (Figure 1).

The conclusion is inescapable: Agriculture is no longer the anchor of the rural economy. It is important—let there be no mistake. But a healthy agriculture no longer assures a healthy rural economy, as it once did. Thus if policymakers want to help shape the economic future of all of rural America, they must engage a much broader range of issues and economic engines. To underscore the point, more rural counties now depend on manufacturing as their primary source of income than depend on agriculture.

The best and worst of times

Rural America has had a lot of economic ups and downs over time.

But through most of those, rural America rose and fell in unison.

That no longer holds because the rural economic base is so diverse.

With that diversity comes a more complex dynamic in the rural

economy.

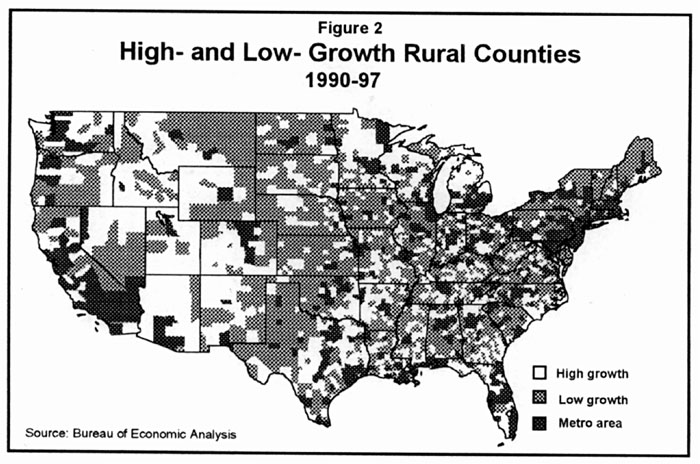

Today, rural America is a striking combination of the best and worst of times. While some parts have fully participated in the nation's long-running expansion, many others have simply been left behind. Employment growth, one broad yardstick of economic growth, paints a clear picture of economic fits and starts across the nation. On the surface, the 1990s have seen a strong rural economic rebound, with job gains nearly matching the "rural renaissance" rate of the 1970s.

Yet those gains have not been widely shared. Four in every 10 rural counties have captured nearly all the growth (Figure 2). These rural growth havens generally have three key traits. Some are next to major cities and are being "suburbanized." Others have striking scenic amenities, such as mountains or lakes. Still others are emerging hubs of rural commerce, providing retail, financial and health services to an ever-widening rural area.

The biggest rural economic gains, therefore, are flowing to regions like the Intermountain West, the Ozarks and rural counties that benefit from market access, such as the counties along I-80 in Nebraska or the ones next to the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area. Many rural counties with scenic amenities are booming. Meanwhile, a large swath of the Heartland has struggled with modest economic gains at best. Most of these counties remain heavily tied to traditional rural economic bases, including agriculture. In many cases, the economic problems in lagging counties are compounded by a shrinking population.

In short, it is both the best and worst of times in rural communities across America. That diversity reflects the wide range of economic bases, but it also poses serious questions about the future for rural people and their communities.

The changes in rural America give policymakers pause as they consider how to help. For more than a century, the federal policy response to rural America was built on the premise that a strong agriculture was the path to a stronger rural America. That just isn't true today. Moreover, the ups and downs of the farm economy became the plan for charting government's policy response. Rural America is now far too diverse for that game plan. Some rural communities struggle with growth pains while others struggle to find any growth at all.

Rural America's Unique Challenges

Rural America's recent economic performance serves as a strong reminder that this vital part of the nation remains unique. The ebb and flow of rural industries, ever-changing forces of technology and an expanding circle of global trade give rural America its own drumbeat.

Looking ahead, what will be rural America's special challenges in the 21st century? What targets will be the north stars to guide policy responses? Five stand out.

Closing the digital divide

Helping rural America tap new digital technologies will be a good

starting point, because such technologies offer the best hope

of closing the distances that have historically left rural communities

behind in the nation's economic race. Distance from metropolitan

areas has been a defining feature of rural America. Without the

benefits of big local markets, such distance left many rural areas

dependent on industries like agriculture or forestry that could

exploit local natural resources. Digital technologies offer a

whole new paradigm—knowledge-based industries located anywhere.

Until now, however, such industries have mostly chosen not to locate in rural America. There are well-publicized exceptions, to be sure. It is possible to be a highly successful software or computer company on the prairie. Gateway 2000 is a visible example (still, it recently moved its headquarters from South Dakota to San Diego). But exceptions do not make a trend. The high-tech trend is decidedly metropolitan, with powerful evidence in Silicon Valley. While no one knows exactly what share of digital age companies are in rural America, anecdotal evidence suggests a sprinkling here and there. Most high-tech firms that locate in rural America generally do so because the owner is getting off the corporate treadmill and going home—a return to Main Street, if you will.

Can rural communities capture more of the digital age in the 21st century? This may be the biggest wild card in rural America's future. Digital technology clearly has the potential to open up bold new economic vistas in rural places. But it will not be easily done.

One challenge is wiring rural America. Hinterland communities simply do not have the same access to the digital age as do most Americans. Entering the Internet is still a long distance call in many rural telephone districts. And DSL is but a mirage. Such infrastructure is "must-have" for many high-tech firms.

Closing this digital divide is not a simple task. Telecommunication companies rightly argue that it is cost-prohibitive to lay fiber optic lines when so few customers are on the other end. Yet they also argue that additional changes in federal regulations might make it possible to justify new rural investments. For instance, current law prohibits Baby Bell firms from carrying phone or data transmissions across state lines. Such rules make it very difficult for companies to combine rural markets that straddle state lines.

Innovation in technology will be another part of the answer. Wireless technologies may open new opportunities for rural people and places. But other technologies that make telecommunication more available may also be needed.

Ultimately, digital access may enter the public policy arena in the same way the nation debated mail delivery and interstate highways. Will rural people drive the information superhighway to the same extent they now drive interstate highways? Time will tell.

Energizing entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs are the yeast in the economy. A tiny part of the

overall recipe, they are the essential ingredient that makes the

economy rise. Many now wonder if rural America has enough yeast

to rise to the fullest.

To a large degree, rural entrepreneurs have become the "homesteaders" of the last century. They tilt against the wind, pursuing their fortune in new endeavors. But beyond this sense of mission, which is common to all business start-ups, rural entrepreneurs tend to be solitary, far from the abundant support systems of the metroplex.

Access to capital provides one window on the rural entrepreneur's world. A new business in suburbia can obtain capital from a legion of sources: the local bank, the regional bank, the national bank, the finance company, the venture capital firm, the local network of angel investors, mezzanine finance companies. The rural entrepreneur, on the other hand, generally has one source: the community bank. Ironically, even local farmers have more capital choices (which include the Farm Credit System, insurance companies, the Farm Service Agency and foreign banks, like Rabobank).

Capital, of course, is only one piece of the puzzle a new rural business must put together. Understanding input and product markets, assembling a business plan, putting together a management team, hiring workers, finding a location, ironing out logistics—all these steps have to come together like a symphony. Many of these steps are simply more difficult to pull off from a rural location. Moreover, a support group to help navigate the process is far more limited.

Herein lies the opportunity for public institutions. Like the homesteaders of the 19th century, rural entrepreneurs need a helping hand. That help includes technology transfer, business and technical assistance, and assisting states and communities in building the infrastructure that will foster successful businesses. This field of opportunity for public universities and others is truly vast.

Leveraging the new agriculture

One of the heralds of the 21st century is a new agriculture. By

new agriculture, I refer to the brave new world of engineered,

and in many cases genetically modified, products for food, medicine

and a host of other uses. While much work remains to realize its

full potential, the new agriculture poses a special set of challenges

for rural America. Put simply, the new agriculture means a new

way of doing business, a trend that many now call supply chains.

Supply chains will literally redraw the rural landscape.

As an aside, whether the new agriculture fully emerges will depend heavily on the ability of agricultural scientists in the public and private sectors to demonstrate its clear benefits to society while showing that attendant risks are minuscule. This will be no small feat in and of itself, especially in a global marketplace where views of science differ greatly.

The new agriculture represents a tidal change in how U.S. agriculture does business, who does business and where it does business. The how involves a shift from commodities to finely graded products and a shift from spot and futures markets to contracts. Many farmers no longer grow generic commodities, but instead have signed on as the first link in a more tightly choreographed food system. The key component in this choreography is a business alliance known as a supply chain. In a supply chain, farmers sign a contract with a major food company to deliver precisely grown farm products on a pre-set schedule.

The who involves a much smaller group of producers. The number is held down since the firm putting the chain together wants to minimize the costs of managing highly integrated business alliances. For instance, industry participants now believe that 40 or fewer chains will control nearly all U.S. pork production in a matter of a few years, and that these chains will engage a mere fraction of the 100,000 hog farms now scattered across the nation. Thus, farmers increasingly ask themselves how they will remain part of rapidly changing business. Without doubt, some will be left on the outside looking in.

The where involves a redrawing of the rural landscape. Supply chains bring a whole new geography to U.S. agriculture. Historically, the economic gains from agricultural science have been widely dispersed. Hybrid seed corn, for example, ultimately went into cultivation across more than 1,000 miles of the nation's mid-section.

The geography of the new agriculture could be very different. It may be based on geographic concentration, not dispersion. With tightly coordinated production and processing, activity tends to move to hubs. In that sense, the poultry industry may be prelude to the future. The poultry industry is now characterized by a handful of supply chains concentrated mostly in the South, the mid-Atlantic and the Upper Midwest. What may be even more striking is that poultry processing and production have concentrated in relatively few rural places within these regions.

The shift to supply chains thus marks a veritable revolution for rural America. To be sure, a "sea" of commodity agriculture will continue for the foreseeable future. The struggle for these "commodity communities" will be building an economic future with fewer farms, fewer banks and fewer businesses. In the end, this probably means far fewer farm communities.

Meanwhile, more and bigger "islands" of specialized supply chains will spring up. Rural communities that hitch themselves to the new agriculture will benefit from the jobs that processing activity will bring, as well as the prospect of higher incomes for large local producers. Still, supply chains will locate in relatively few rural communities. And with fewer farmers and fewer suppliers where they do locate, the economic impact will be different than with the commodity agriculture of the past.

How can the many benefits of the new agriculture be leveraged in favor of rural America? One issue will be the number of new products moving into commercial production. The more there are the more rural communities that will benefit. This speaks to the overall amount being spent on research and development—by both the private and public sectors. Land grant universities, which represent the public stake in agricultural research, clearly have a role in helping rural America source a wide range of products in the next century.

Another issue will be thinking seriously about which products will be well suited to parts of rural America where an economic boost is sorely needed. Some products may have unique geographic qualities. Others with such traits might be developed with some additional research effort. A final issue is helping communities position themselves to be supply chain hubs. This will require much more than just a viable product—it will involve infrastructure, local leadership, capital, education and a host of other local factors. An overriding challenge will be putting all the pieces together into viable community plans.

Land grant universities and state government will be well positioned to influence all these issues. They can require that researchers think through the rural impacts of new products—and which rural places stand to win and lose. They can also be a catalyst in helping communities position themselves as new agriculture hubs. This will require coordinating university research and extension with state economic development initiatives.

Sustaining the rural landscape

The countryside has always been a dominant feature of rural America.

The economic forces now swirling across rural America increasingly

put that countryside at risk. The risk takes many forms. Environmental

concerns mount where new agriculture supply chains now concentrate—especially

when they involve livestock. Land use concerns rise in rural places

that are booming as congestion erodes the quality of the spaces

that attracted people in the first place. Dwindling numbers of

farms raise doubts about the "farmscape" of the next century.

And falling population in many rural places prompt new calls to

improve the quality of life for those that remain.

The very breadth of these concerns means that no one response will address them all. Still, two themes may merit special attention.

A concerted effort to integrate the environmental, economic and production aspects of the new agriculture is clearly needed. While environmental and production issues are receiving a lot of attention, the economic dimension may be missing. The hog industry provides a good example. This $28 billion industry is in the midst of a revolution, as it rapidly shifts from independent producers scattered throughout the nation to a supply chain structure concentrated in relatively few locations. The environmental issues that go along with huge livestock facilities are the focus of a new generation of research. But the industry is moving so fast that location decisions may be made before that research bears fruit. In particular, the industry is looking seriously at expansion in Canada, Mexico, Brazil and even Poland instead of the United States.

Thus, there needs to be a much more comprehensive assessment of the industry's options in rural America. What is needed to keep the industry in rural America? What environmental restrictions are in the interests of industry and rural communities alike? Public officials must be willing to synthesize all three dimensions of the issue in order to succeed.

The second theme is rural quality of life. Many rural observers blithely assume that quality of life is a rural asset. But to borrow the Gershwin line, it ain't necessarily so. Dwindling population throughout much of the nation's Heartland is putting enormous pressure on the rural tax base—raising fresh doubts over rural education and a host of public services. The days of county courthouses as the mechanism for delivering public services may be in the past in some parts of rural America.

Quality of life issues also have a huge impact on some of the most important votes cast in rural America—the votes young people in rural America make with their feet. A frequent lament in many rural quarters is the loss of the best and brightest to the nation's metroplexes. While some would argue the market is working, in at least some cases the next generation would stay if rural communities offered more.

What it takes to boost the rural quality of life is not readily answered. But it certainly goes beyond rural electricity and mail delivery—two battles over rural quality of life in decades past. The digital issues discussed above clearly bear on quality of life. But a host of intangibles also enter in, such as access to cultural events, sporting events and learning opportunities.

Bucolic lifestyles no longer characterize the vast majority of rural Americans. For them, the future is much more about assembling a bundle of lifestyle accoutrements that make rural life richer. In many parts of rural America, that bundle appears to be getting smaller, not bigger. Policymakers clearly have a new opportunity to help replenish the bundle.

Boosting human capital

Lastly, a transcending challenge will be boosting rural America's

human capital. Building new futures for rural America depends

more than anything on the people who will make it happen.

Studies show that rural America has a smaller share of people with college training than metropolitan areas have. This brain drain simply makes it that much harder to do a whole host of things in rural America—stoking entrepreneurism and attracting high-skill jobs to name two. Slowing that drain will depend on creating more viable economic opportunities and enhancing rural quality of life.

The brain drain just noted is a big issue, but not the only one. Lifting the skills of rural workers and building leadership capacity in rural communities will also be critical. Higher worker skills will be a major plank in building a brighter rural economic future. Rural wages appear to be falling behind those in metro areas. In the 1990s, for instance, rural wages have risen less than half as fast as metro wages. One graphic example of a rural wage problem is the meat packing and processing industry. The meat industry is a huge one in rural America—employing more workers than any other manufacturing industry. Yet wages in this industry have fallen sharply in real terms over the past decade—30 to 40 percent depending on the region.

Lifting wages will require higher skills and more rural entrepreneurs. This presents something of a "chicken and egg" problem. Which comes first, better firms or better workers? The answer, of course, is yes. It takes both. Rural workers will be a crucial target for new lifelong learning initiatives. Rural people not only need access to the information superhighway, they also need to be adept in traveling it.

Finally, rural communities will need more than high-skill workers and a new generation of entrepreneurs. They will need strong local leaders. As never before, firms have myriad choices when they locate. Those choices now cross county lines, city limits, state lines and national borders. Rural communities have trouble competing in this race due to their small scale. Thus, rural leaders need to be especially effective. Training effective rural leaders will be a key to helping rural communities remain viable in the new century.

A New Generation of Rural Policies

Ultimately, rural America will have to meet its own challenges. The real question is the extent to which public policy plays a supporting role. This question is wide open, because history is probably not a reliable guide in offering an answer.

Historically, rural America has been the target of many policy initiatives, ranging from the Homestead Act to rural electrification, from the creation of land grant universities and the extension service to decades of agricultural policy, from rural mail delivery to interstate transportation and highways. Yet many of these policies have had agriculture at their soul. And those not aimed at agriculture generally have not been coordinated with the rest.

In short, the United States has not had a coherent "rural" policy. It has had a collection of programs that each affect rural America, but with no comprehensive slate of goals nor a coordinating mechanism to guide them. According to Bonnen and others, to a large degree this reflects the general lack of a clearly defined "rural" constituency, especially when compared with well-organized farm groups.

This agricultural legacy is evident throughout the institutions that will shape rural America's future. Congress has agriculture committees, not rural committees. The same is true in most statehouses. Land grant universities have colleges of agriculture, not colleges of rural studies. (Interestingly, many universities do have urban studies programs.) The extension service remains targeted mainly at agriculture, although some states do make rural issues a priority.

The big question for rural policy going forward, therefore, may not be a matter of what but how and who. There will be some disagreement, to be sure, on the exact priority of rural America's challenges in the next century. But the general tenor of those challenges is clear. What is much less clear is who will craft policies to meet them, and how those policies will be debated and implemented.

Regardless of the who and how, rural policy initiatives in the next century will need to contain some core building blocks to be effective. The first of these is a clear set of goals. While the nation is well acquainted with debating the goals of agricultural policy, there has been much less discussion of the goals for rural policy. Just what does the nation hope to achieve with any new rural initiatives?

Four goals may receive widespread consideration. Easing economic adjustments in rural America will be a likely near-term goal. Some rural people lack the mobility to adjust readily to the economic changes sweeping rural America, and many rural resources are fixed in place. I will be high on the list for places like the Heartland, where rural economic engines are sputtering. Stewarding the rural landscape may be a priority for rural and metropolitan Americans alike, with scenic and rural cultural amenities drawing new attention. Finally, avoiding some of the costs of ever-widening metroplexes may underpin new rural initiatives. The costs of congestion and sprawl are coming under greater scrutiny in places like Atlanta. Georgia's governor, for instance, has proposed a development plan that encourages rural development in part to avoid further congestion in Atlanta.

A second core building block will be policy institutions. The who in new rural policies is not at all obvious. Will it be a federal, state or local undertaking? Or all of the above? Which committees in Congress might mount new rural policy discussions? Which state agencies will provide oversight for new rural initiatives? Answers to these questions are not clear, especially in a world where rural meant agriculture for so long.

There are signs that institutional innovation may be under way. Thirty-six states have rural development councils, cross-cutting groups that examine rural issues at the state level. These councils grew out of a pilot program tucked away in the 1990 farm bill (which spawned councils in eight charter states). These councils have now pooled their efforts as the National Rural Development Partnership. This organization may become a forum for more active debate and development of rural policies going forward.

Conclusions

Rural America is undergoing enormous change. Agriculture is no longer the tide that carries rural America. It's a strong force, but it no longer assures rural economic success. In fact, rural America has become a striking mix of the best and worst of times, highlighting the need for finding new ways to lift the rural economy.

Against these and other changes, five challenges will be crucial hurdles in opening new economic horizons for rural America. Closing the digital divide will help rural America compete in a new high-tech race. Urging on rural entrepreneurs will provide new fuel for a sputtering rural economy. Leveraging the new agriculture will help more rural communities benefit from the new frontiers of agricultural science. Sustaining the rural environment will provide a rich, vibrant countryside that attracts and retains those who choose rural lifestyles. And boosting human capital will equip rural workers and leaders for a new century of challenges.

While a new century of challenges ultimately falls to rural communities themselves, public policy will play a supporting role. Yet what that role will be is far from clear. Agricultural policy, the historical response to rural matters, will not address the broad range of rural challenges by itself. And whether and how the nation moves beyond agricultural policy may be one of the most interesting questions awaiting an answer in the new millennium.

Center for the Study of Rural AmericaTo better understand the forces that will shape rural America's future, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City has established the Center for the Study of Rural America, a unit in the bank's Research Division. The Center will expand the bank's current economic research on the farm and rural economies to a national level. Researchers will produce studies and analyses of rural and agricultural issues of importance to the Federal Reserve System, other public policymakers and the general public. Along with tracking changes in rural and farm economies, the Center will host an annual conference, produce in-depth studies, publish a monthly newsletter (The Main Street Economist) and prepare an annual report on the state of the rural economy. See more information on the the Center from the Kansas City Fed's website. |

For further reading

Bonnen, James T., 1992. "Why is There No Coherent U.S. Rural Policy?" Policy Studies Journal, vol. 20 (2), pp. 190-210.

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 1996. Economic Forces Shaping the Rural Heartland.

Rasmussen, Wayne D., 1989. "90 Years of Rural Development Programs," Rural Development Perspectives, October, pp. 2-9.

Trujillo, Solomon D., 1999. "Technology: The New Infrastructure for a New Rural America," in Equity for Rural America: From Wall Street to Main Street, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 99-106.