In speeches describing hard times in rural North Dakota, Sen. Byron Dorgan often relates the story of a conversation he had with a Lutheran minister in New England, a small town in his home county of Hettinger in the southwest corner of the state. At her church, the minister told him, she holds four funerals for every wedding. "People are moving out of town, not into town," observes Dorgan in his speech. "The people who stay are getting older—and are dying."

Recalling her conversation with the senator, Rev. Donna Dohrmann verifies the funeral-to-wedding ratio. "I would say 4-to-1 is pretty accurate," she remarked. "We bury more than we marry." But she added an even more disheartening detail. "Most of the weddings were kids who didn't even live in town any longer. They'd just come back to hold the wedding and then leave again." The funerals, on the other hand, were all local.

Dohrmann herself has now left for a new job in Bismarck, but she remembers New England fondly. It's a town where people watch out for one another, she said, and have a sense of humor. "When I first moved there," she recalled, "there was a sign that said '660 people and 2 old grumps.' Well, it wasn't long before people told me I had buried one of the grumps. And I doubt there are 660 people there still." Indeed, the U.S. Census estimated the 2002 population at 527; more than a quarter of them are over 65.

The town of New England, the county of Hettinger and the state of North Dakota, are among the oldest in the nation. But in the Ninth District, they are far from unique. Indeed, almost three-quarters of the district's 303 counties fall above the national median for percent of county population 65 and over. If you exclude Florida and several counties on either coast, a map of the nation's oldest counties resembles a swath of gray broadening like a funnel as it rises from south to north, with a narrow tip in central Texas and a wide top stretching across the Ninth District, from the center of Montana, through much of the Dakotas, western and northern Minnesota, into northwestern Wisconsin and Michigan's Upper Peninsula (U.P.).

South Dakota has more centenarians per capita than any state in the nation. North Dakota ranks highest in those 85 and over per capita. North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana respectively rank fifth, eighth and 14th in national rankings of states for percent of population age 65 and older.

Minnesota's overall population skews younger, but it has deep pockets of concentrated elderly. Traverse, Lincoln and Big Stone counties, running along the western border, rank in the top 100 nationally for seniors as a percentage of population. Their western neighbors and several counties on Minnesota's southern border don't fall far behind.

Most counties in northwestern Wisconsin and the U.P. run old as well. Twenty-one of Wisconsin's 26 district counties have higher senior concentrations than the national average; 18 are older than the Wisconsin average, and six have about 20 percent senior populations. Similarly, 13 of 15 U.P. counties fall above the state and national averages and four have 20 percent or higher senior populations.

In fact, of the nation's 100 oldest counties, ranked by percent of population 65 and above, nearly one-third fall in the Ninth District. See population maps.

Top-heavy pyramids

There are definite exceptions to the aging pattern. Parts of western Montana, counties with large Indian reservations (which generally have high birth rates and lower life expectancy), communities with colleges or prisons, and metropolitan areas such as Fargo-Moorhead, Sioux Falls and the Twin Cities have younger populations. But by and large, district counties are grayer than national norms. And they're rapidly getting grayer.

Demographers like to talk about population pyramids, graphic representations of the age structure of a given society. The bottom of the pyramid shows the percent of population made up by its youngest generation; at the peak are the elders. As the term implies, the usual population pyramid has a very broad base and a small pointed top.

But in the Ninth District, while some counties follow the standard pattern, most are becoming population cylinders with tops and middles about as wide as the base, and an increasing number actually have top tiers that are beginning to dwarf the bottom. Divide County, at the northwestern corner of North Dakota, for example, currently has a pyramid that resembles a lumpy bar standing on its end. By 2020, though, it will be a top-heavy pyramid. McPherson in South Dakota, Traverse in Minnesota, Iron in Wisconsin and Ontonagon in the U.P. all have roughly the same story.

A powerful factor behind this trend, one that has its deepest impact on small rural counties, is migration. The young tend to leave rural areas, to go to college or to find a job. And older residents stay or return. Steve Seninger, director of economic analysis at the University of Montana-Missoula's Bureau of Business and Economic Research, put it in a nutshell. "[Montana has] out-migration of younger persons, return migration of older middle-age former Montana residents and in-migration of retirees."

And as small towns like New England have discovered, it's the oldest citizens who are most permanent. "We have out-migration of seniors who are in their early retirement and preretirement ages, so if you start at 55 and go all the way to about 75, you'll see out-migration," said Richard Rathge of the North Dakota State Data Center. "However, when you start getting what we call the older seniors, and that's when you get to 85 and over ... all of a sudden you see that we have reverse migration. People will retire, leave, go to the Southwest and so forth, but when they lose mobility, when they lose a spouse, when they lose a significant caregiver or what have you, then they come back to the informal care networks where they grew up. And that's what we're seeing in the Great Plains."

But other forces are at work. The huge baby boom generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—is inexorably making its way into progressively older age categories, bulging upwards through the pyramid like a pig in a python. In addition, life expectancies have risen so the old are with us longer. And fertility rates have stabilized or fallen for many population groups, especially those in most rural counties, so fewer babies fill the lower level of the age distribution. The combination of these factors produces a demographic inevitability: For many counties—particularly those not near metropolitan areas—the age structures are beginning to resemble toppling pyramids, with significant increases in the percentage of population 65 or older.

And the future

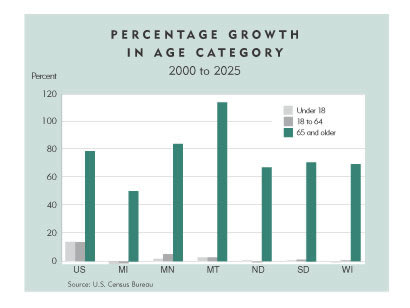

As demographers look forward at the Ninth District, projections vary state by state, but there is one constant: In all six states, the older population groups will grow dramatically in both absolute and relative terms (see chart).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

In Minnesota, for instance, the state demographer projects 27 percent growth in the population as a whole between 2000 and 2030. But while the population age 0 to 44 will grow about 9 percent during that time, the 45-to-64 age group will grow 35 percent, and the senior population will grow 117 percent. By that time, 21 percent of Minnesotans will be 65 or over, compared with 12 percent today.

Michigan hasn't projected quite that far into the future, but the U.P.—already rather old—is likely to grow still grayer in coming decades. The 15 U.P. counties average about 18 percent of the population 65 and older in 2000. By 2020, say state projections, U.P. counties will average 25 percent seniors. In some counties, that growth will be staggering. About 20 percent of Keweenaw residents are 65 or over now. By 2020: 43 percent.

Wisconsin's district counties will increase their senior percentages from an average of 16 percent now to 22 percent in 20 years. In Burnett, Vilas and Iron counties, nearly one-third of the population will be 65 or over. "In northwestern Wisconsin, counties that are just across the river from Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area will stay pretty young," said David Egan-Robertson of Wisconsin's Demographic Service Center. "But you get into the more rural counties where it's more of a retirement or an agricultural base, you'll see pretty rapid aging."

Montana already ranks 14th nationally in percent of population 65 and older. But according to U.S. Census projections, it's gaining fast on its rivals, surpassing both Dakotas, and is likely to rank third or fourth by 2020. "The major problem of aging population is in the declining agricultural [and] ranching counties in eastern and north-central Montana," observed the University of Montana's Seninger.

South Dakota, now the nation's eighth oldest state, will continue to age as well. From 2000 to 2020, its overall population is projected to increase about 11 percent, but its senior population will climb 66 percent. By 2025, according to De Vee Dykstra at the University of South Dakota, 25 percent of the state's population will be 65 or over, and the number of residents 85 years and over is expected to double between 1990 and 2020.

And North Dakota, currently the nation's fifth oldest state, will grow older still. In 1980, 12.3 percent of its population was 65 or older—roughly what the nation is now. By 2000, the proportion had climbed to 14.7 percent. By 2020, it's expected to hit 23 percent.

So what?

We're getting older. Does it matter? In talking about the "burden" that the old place on the young, experts usually refer to the "elderly dependency ratio," the ratio of those 65 and over to the working-age population. It's an approximation of how many old are supported by how many workers. (Of course, not everyone is employed and not all seniors are retired, but it's a rough gauge.) A different way of stating the same problem is its inverse: the number of workers per seniors.

By either gauge, there will be a significant shift in the next two decades (see chart). In Michigan and Minnesota, there were about five workers per senior in 2000, according to the U.S. Census. In Montana and Wisconsin, there were roughly 4.6 workers per senior and in North and South Dakota, about four workers per senior. But by 2025, the Census projects these numbers will fall to about three in Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin, roughly 2.5 in the Dakotas and just over two workers per senior in Montana.

Similar numbers come from the Social Security Administration, which estimates that nationally in 1950 there were 16.5 workers contributing to the Social Security trust fund for every one beneficiary. By 1990 there were 3.4 contributors per beneficiary, and by 2030 the SSA projects there will be just 2.1 workers contributing to Social Security for every one who draws a check.

But Social Security isn't likely to be the most daunting expense, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Social Security expenditures are projected to rise modestly between 2000 and 2030, from about 4.2 percent of gross domestic product in 2000 to 6.2 percent in 2030, and level out thereafter, according to CBO projections. But outlays for Medicare (the federal health program for the elderly) and Medicaid (the federal health program for the poor, disabled and indigent elderly) will climb dramatically as the population ages and health costs rise, from 3.4 percent currently to nearly 8 percent in 2030 and climbing to almost 15 percent by 2075. The CBO estimates were made prior to the 2003 Medicare reforms, which will increase costs substantially.

Local aging, local costs

Medicare and Social Security expenditures can be addressed only by policy reform at the national level. But other costs related to an aging population are borne more directly by states, cities and local communities. And those costs will grow.

"All of the health care cost increases that we've seen recently have really happened before the major aging of the population has occurred," observed LaRhae Knatterud, planning director for Minnesota's Project 2030 Aging Initiative at the Department of Human Services. "So if that's already happened and we're not even really old yet, we could be in line for some major increases."

To put some figures on that reality, the Minnesota Department of Health analyzed the implications of Minnesota's aging population for health care costs. The hospitalization rate for baby boomers in 2000 was less than 10 per 100 population, according to the MDH's 2003 report. But for those 65 to 74, the rate nearly tripled, and for those 85 or over, it was about 60 per 100.

Given the growing population in Minnesota and its aging, the report projects a 56 percent increase in hospitalizations over the next 30 years and over half of that increase will be due simply to the fact that the population is older. "The increased demand for inpatient hospital services," said the report, "is likely to create strains on Minnesota's hospital system." The cost implications are significant. "Health care spending per person age 65 and over was more than three times the average of the population under 65 in 2000," it noted. "In the coming years, increasing demand for services as a result of population aging will emerge as a more important cost driver, adding to the significant cost pressures already being felt in the system."

Sharing the burden

The impact of these increased costs will be felt first by private insurers and employers, and some companies have already begun to shed responsibility for retiree health coverage. According to a national survey of large employers released in January, one in five said they might drop health care coverage for future retirees in the next three years and almost three-quarters of them had made retirees pay a larger portion of health insurance premiums.

But states will share the burden as the population ages further and more residents become eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. While Medicare is funded entirely by the federal government, Medicaid's costs are split between states and the federal government. In Minnesota, for example, the state government pays about 47 percent of Minnesota's Medicaid expenditure. And although three-quarters of Medicaid's beneficiaries, nationally, are children and nondisabled adults, three-quarters of the costs are for the elderly or disabled. As Minnesota's state economist Tom Stinson told the Minneapolis StarTribune last August: "The issue isn't single parents with three kids. It's senior citizens and nursing home care."

The Medicaid issue isn't just Minnesota's of course. In fiscal year 2002, Medicaid accounted for 21 percent of all state expenditures, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers (see chart). State spending on Medicaid had grown by 11 percent over the previous year and has begun to crowd out other public spending, said NASBO. Since 1987, Medicaid's share of state expenditure has soared 104 percent, according to fedgazette analysis of NASBO data. The only other state budget category to have increased its piece of the pie in that time span was corrections, with a 20 percent rise. The share of state spending devoted to transportation dropped 24 percent; elementary and secondary education costs take 5 percent less of the state budget pie than they did in 1987.

* Note: "Workers," are residents between 18 and 64 years old. "Seniors" are those 65 and older. |

Source: State Expenditure Reports, National Association of State Budget Offices |

Looking to its future, North Dakota's Legislature funded a comprehensive study in 2002 of the long-term care needs of its aging population and asked for policy recommendations based on its findings. The study, coordinated by the North Dakota State Data Center and the Center for Rural Health, determined that the number of seniors with functional limitations is higher than the national norm but that more than half of the state's 53 counties lack an assisted living facility, basic care facility or senior residential facility. The report called for program initiatives and tax incentives for home and community-based services to "reduce the demand for institutional care and, in turn, the financial burden on the state."

Minnesota's similar effort, Project 2030, noted that families currently provide 95 percent of all care for seniors in Minnesota, but by 2030, fewer of the elderly will have families to rely on. Many Minnesota counties already have high ratios of people 85 and older to females age 45 to 64 (the customary caregivers). "Many of the rural counties are already experiencing the demographics of 2030," said the project's Knatterud.

While federal or state funding has often been the main source for programs for the elderly, counties are also feeling the crunch. Charlie Rehbein, bureau chief of Montana Aging Services, noted that counties often provide matching funds for senior services such as nutrition programs, transportation services and the like. "They can do a mil levy for transportation and a mil levy for the senior center program, so there's some revenues out there that can be used specifically for the elderly," observed Rehbein. But in eastern and north-central Montana, where seniors comprise a high portion of the population, due in part to out-migration of the young, tax revenues can be hard to come by. "If you don't have people moving into your community, the value of the property isn't going up," said Rehbein. "That comes into play when you're talking about mil levy funding."

Tough decisions

Similar fiscal constraints affect senior programs throughout the district. "Whenever the counties have concerns about their tax revenues or about cutbacks, like the local aid cutbacks that happened in Minnesota, they have to scrutinize what they're doing," noted Knatterud. "We've heard a number of stories just in the last year of counties having to make a decision between, for example, the van service that serves primarily elderly or some kind of battered women's shelter that is important for women in abuse situations. It comes down to some very tough decisions that the counties have to make."

As the population ages, decision makers at all levels will be faced with daunting choices. Employers will face decisions about pensions and other retiree benefits, state legislators will decide about program funding, national policymakers may have to choose between decreasing Social Security benefits or increasing payroll taxes. In making such decisions, the most difficult step may simply be accepting the fact that we're aging, and acknowledging that the retirement advice we give to individuals applies to businesses, communities and governments as well.

"We need to be thinking not just two years down the road, because the budget that the legislature passes is for every two years, but 10 to 15 years down the road," said Rehbein. "We need to be looking at our demographics and thinking seriously about how we can fund this stuff. And we should be starting now to put aside money for our old age."

| May 2004 fedgazette: The Graying of the District continues with a look at whether gray might mean gold for district states and communities. |