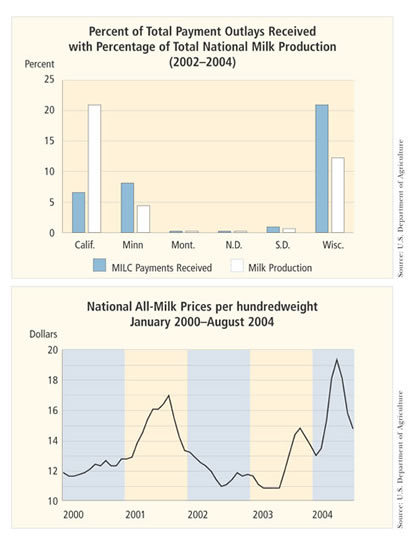

The dairy business in the Ninth District has never been for the faint of heart. The number of farms has been on the decline for decades and, more recently, farmers suffered through a long price slump in 2002 and 2003.

But contrary to what we often hear, in some ways it's a great time to be a small dairy farmer in the Upper Midwest. Those who made it through the low prices have enjoyed record high prices for much of 2004. And if prices drop again, small producers will be able to take advantage, as they did during the last slump, of a generous federal aid program targeted directly at them: the Milk Income Loss Contract, or MILC.

A new element in the already complicated mix of federal dairy programs, MILC was established in the 2002 Farm Bill with the specific intent of keeping the little guy afloat. It is a fundamentally new program providing a direct payment to farmers during periods of low prices, without the purchase of surplus dairy production as in past arrangements.

Like most agriculture subsidies, the workings of MILC require some background. Here's the simple version: The U.S. Department of Agriculture sets a target price for milk. When the monthly market price dips below the target, the USDA pays farmers part of the difference. The payments stop at a production cap to ensure the money is targeted at small farms.

It may seem like the program would make everybody happy; it protects the "family farmer" without directly manipulating the price consumers pay. But the program has not been without controversy. Critics charge that MILC is nothing more than a handout that encourages outmoded, inefficient production. They say it discriminates against large farmers who now provide the majority of the nation's milk, and that it has more of a distorting effect on markets than proponents let on.

What's more, the program has been more expensive than first thought. It was originally projected to cost $1.3 billion from its inception in 2002 to its expiration in September 2005. As of May, when the last payments halted after prices shot up, MILC had poured out $2 billion.

The issue isn't likely to get less controversial anytime soon. Politicians from Ninth District states, where a disproportionate amount of payments have gone, introduced new legislation in both the House and Senate to extend MILC beyond its expiration next year. With a big debate on the future of dairy policy coming up, it's worth examining the effectiveness of the program.

Dairy policy background

MILC is one of the latest in a tangled web of dairy policies that date back to the Depression.

The mother of all dairy policies is the Federal Milk Marketing Order. The FMMO, which grew out of agricultural legislation in the 1930s, was set up to ensure that communities had drinkable milk and to provide some stability for farmers. It did so by mandating prices paid to producers for drinkable milk. Prices were based on intended use and geographic region. This was the source of the infamous "Eau Claire rule" that set prices as a function of distance from Eau Claire, Wis.

The program has expanded and changed over the years. It is no longer for drinking milk only; in fact when taking into account California, which has its own system, 90 percent of all milk produced in the United States is price-regulated.

The 1996 Farm Bill established a reform process for the FMMO, but most of the suggested changes were not a hit with lawmakers, and only some of them were followed. The system is now much the same as it has always been, although the Eau Claire rule has been abandoned. The new pricing formula, determined by the National Agricultural Statistics Service survey, places the lowest price in Minnesota and Wisconsin, so the regional effects are mostly the same.

The other major historical policy is the Dairy Price Support Program, which began in the 1940s to provide a safety net. Under the DPSP, the government purchases storable dairy goods—cheese, butter and nonfat dry milk—when they fall below a certain price, currently $9.90 per hundredweight. The intent is to create a market for surplus production and to provide a minimum price level.

By the early 1990s, however, it was recognized that the DPSP was distorting dairy markets. The 1996 Farm Bill set in motion a plan to phase out the program completely by 1999. As with the FMMO, legislators later amended those provisions. In 2002, the program was permanently reauthorized.

MILC-ing the system

The survival of the DPSP and FMMO was also the political genesis of MILC. These programs were intended to support the traditional (read: small) dairy farms, particularly in New England. As the traditional programs came under attack, legislators from Eastern states set about creating new protections expressly for New England dairy farmers in the 1996 Farm Bill. This led to the Northeast Interstate Dairy Compact.

The Northeast compact allowed six states—Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont—to set up a special price support system for Class I, or drinking, milk. This set off a storm of controversy among farmers in other regions, especially after Congress extended the program without allowing other states to create compacts. By the time the 2002 Farm Bill was being put together, the program was too unpopular to continue, so legislators were making deals behind the scenes to come up with a replacement. Not even farm organizations had a clear idea of what that should be.

"We did not propose the MILC payment," said Jerry Kozak, president and CEO of the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF), the lobbying group representing dairy farmers and cooperatives. There was a "significant split within the membership," regarding the compact, Kozak said, "so we stayed out of that." The split was largely along regional lines, with members from large-producer states in opposition, citing the favoritism toward small producers.

"Now, where the MILC payment program came from is pretty clear; the legislators in the Northeast continued to try to get an extension and reauthorization of the Northeast Dairy Compact," Kozak said. Supporters of the compact knew there was not enough support in Congress to reauthorize it, so "they began looking at another safety net program that they could make somewhat equivalent to what they would be losing in the Northeast Compact."

The MILC program in force today, not surprisingly, is very similar to the arrangement under the Northeast Compact. Farmers receive 45 percent of the difference between the Boston Class I price and a target of $16.94 per hundredweight. The payments are only in effect on the first 2.4 million pounds of annual milk production, to keep the money targeted at small producers.

It takes a farm with 130 cows to produce an output of 2.4 million pounds in a year, assuming a rate of 18,000 pounds per cow, which is about average. Nationwide, 81 percent of all dairy farms have fewer than 200 cows. But the largest 9 percent of farms—many in Western states—account for more than 60 percent of national milk production.

In an interesting twist, the program, which was introduced by legislators from the Northeast, particularly Vermont, has become much more popular in the Upper Midwest. Farmers in Minnesota and Wisconsin are now receiving large portions of the payments because there are a lot of small farms in those states.

To get an idea who the program is intended for, consider some recent numbers. Of the approximately 16,400 dairy farms in Wisconsin, 88 percent produced less than 2.4 million pounds of milk. In Minnesota, the figure was about 90 percent of all 6,200 dairy farms. In California, now the nation's largest milk producer, only 19 percent of about 2,100 total dairy farms produced less milk than the cap, because dairy farms tend to be very large-scale operations there.

The result is that states with more small producers get more money. Wisconsin is the largest recipient of MILC payments, with a total of $413 million since payments began, or more than 20 percent of the total cost of the program. Minnesota has received $163 million, and California, which produces 20 percent of the nation's milk, received $147 million.

The program has become so popular in the Upper Midwest that some legislators want to change its status from temporary relief to a longer-lived service. Sens. Norm Coleman, R-Minn., and Herb Kohl, D-Wis., have introduced legislation to extend the program, currently set to expire in September 2005, until the end of 2007—the entire life of the 2002 Farm Bill. There is a companion bill in the House as well.

The extension won't pass without a battle; large-herd states like Arizona will likely fight the measure and the Senate version of the bill has a provision to double the production cap. In the end, most observers think the extension will pass. According to Connie Tipton, president and CEO of the International Dairy Foods Association, "The thing we say here in Washington is that all government programs are alike; they have a beginning, a middle and no end."

Costs and benefits

Without a doubt, the program has been the salvation of many small dairy farmers in the Ninth District. Bob Swenson, a dairy farmer in Ellsworth, Wis., with 50 head of cattle, said MILC helped him get through the slump, but that, "the program was like putting a Band-Aid on if you'd cut an artery." Swenson, whose farm has been in his wife's family for around 130 years, was considering subdividing and selling his land. Eventually prices came back up, though he said, "It's looking better now, but the money I lost in those 18 months of low prices is going to take a long time to recover."

According to Ed Jesse, dairy economist at the University of Wisconsin- Madison, while the number of dairy farms continues to drop, the price slump of 2002 and 2003 would likely have put many more out of business had it not been for MILC. As the numbers given above indicate, the program has been particularly favorable toward Ninth District producers. As to whether the program has been good for the industry as a whole, Jesse said, "I'll plead ignorance on that one."

The most prominent unforeseen problem is the cost of the program. MILC has already cost 54 percent more than projected for its entire lifetime, with more than a year to go. The major reason for this overrun was the price slump of 2002 and 2003, which no one predicted. "I guess what I'd say is it was a good program that was implemented during a bad time," said Jesse.

It was only through a combination of other forces that dairy prices shot back up. It started with the discovery last December of a cow from Canada infected with mad cow disease. One of the first precautions was a ban on importing cattle from Canada, which meant fewer replacement heifers for milk production. As the supply of beef dropped, many farmers found it more profitable to slaughter their milk cows for meat, further restricting the supply of milk. Also, agribusiness giant Monsanto experienced production problems for bST (which farmers widely use to increase milk output) and saw hormone supplies drop 50 percent. Other factors include an Australian drought and ensuing decline in imports and the continuing popularity of the Atkins diet, with its celebration of cheese. Now the number of milk cows is back on the rise and prices are expected to level out.

For now, prices have been high so there haven't been any new payments since May. If there aren't any more crises, proponents say, the program shouldn't be too much of a burden.

Hidden costs

However, many observers think MILC had the effect of prolonging the price slump beyond what it would have otherwise been. According to Keith Collins, chief economist for the USDA, the program has had the effect of raising the income farmers receive from milk. "By doing that, it stimulates more production and that lowers prices," Collins said.

Ironically, then, the program may have hurt dairy farmers by keeping more of them in business, leading to an oversupply and lower milk prices. Jesse cautions that while the possibility makes economic sense, it has not been shown conclusively. "If that can be demonstrated, and again it's intuitive as opposed to anybody proving that that's occurred, that would certainly have a negative impact on all dairy producers," he said.

In fact, Kozak believes he can show the program had a price-suppressing effect. Economists at the NMPF calculated the average all-milk price over a 20-year period and compared it with the period of MILC payments. "I think one can conclude ... looking at the raw data, that indeed the MILC payment program certainly was not successful in raising the farmer's price above the average, and prices actually continued to stay below the 20-year average," said Kozak.

Another side effect of MILC relates to a developing agricultural issue—the impact of subsidies on world trade. The MILC program, because it is a commodity-specific direct payment, falls into the World Trade Organization's "amber box" category of the most trade-distorting programs. The United States currently has a cap of $19.1 billion for such programs, what the WTO calls the Aggregate Measure of Support. Dairy programs account for "$5.5 billion or so," Collins said.

The federal government has not yet officially notified the WTO of the current dairy programs. When it does, the result will be an outcry from other subsidy recipients, fines on the United States or cutbacks in MILC.

But perhaps the most detrimental side effect of MILC is its long-term impact on the efficiency of dairy production. At best, say critics, the program is a handout that does little to help modernize dairy farms. At worst, the program blocks market signals and encourages inefficient producers to continue along without getting more competitive, and this could hamper development of the dairy business in the Ninth District, which is already losing ground to other regions.

"It's not helping them build their facilities so they can be more efficient in the future. It's not really creating any sort of long-term benefit, which is one of the problems with that kind of subsidy," Tipton said. "It probably saved some people from going out of business. I don't want to diminish that as an impact, but I just don't think it's the best way to spend my $2 billion, if I had it."

A major problem is that MILC cannot be evaluated alone, since it exists alongside other dairy programs. "We've got this system that was put in place during the Depression that has been tinkered with multiple times, to the point that it is very convoluted; very few people understand it," Tipton said. "You get milk moving through plants that are making it into powder and selling it to the government, when there is a market demand for high-protein dairy ingredients that's having to be met with imports."

Jesse suggested that a more effective and less distorting safety net is possible, by establishing somewhat higher minimum price levels than the current DPSP—$10.10 to $10.50—but paying farmers the entire difference rather than paying them a fraction or purchasing surplus. He would also make payments available to all farmers or impose a "fairly unrestrictive payment limitation." Jesse believes this plan would interfere less with markets, because it would discriminate less against larger producers and because by providing a lower level of support, it would offer less incentive toward overproduction.

But safety nets still suffer from the problem of encouraging inefficiency. So most observers agree on the need for modernization. A major reason for the Western migration of dairy production has been economies of scale. "I think being successful in dairy does not necessarily mean getting a lot bigger, but it does mean becoming more efficient, building the kinds of facilities that, even though they may not be large scale, involve greater labor efficiency," said Jesse.

Meanwhile, Kozak and the NMPF have begun to look for ways to stabilize dairy prices without government support. "When we were going through this period of depressed prices, we came to the conclusion that regardless of government programs and where we're headed with different changes in our industry, that it would be far better to put together a voluntary producer's self-help program, not connected with government and to try to help ourselves strengthen and stabilize prices," he said.

The program that emerged was called Cooperatives Working Together. Participation represents 70 percent of milk production nationally, with fairly large participation in the Upper Midwest. The program coordinates producers to prevent oversupply by buying and retiring herds—300 to date. The group has also started an export assistance program that rewards farmers as exports increase.

Swenson, a member of Cooperatives Working Together, has been impressed with the results so far. "All they have to do is talk about doing something, and the prices go up," Swenson said. "This is what farmers need, the supply management thing," he said, "and I hope it keeps going for a long, long time."

Note: In mid-October the USDA released a detailed analysis of the economic impact of dairy policy. [1.5M PDF] |

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.