Donald W. Quander does not have fond memories of the great energy spike in 2000 and 2001 that forced many of Montana's largest industrial companies to close shop temporarily, reduce workloads or use alternative sources such as diesel generation to continue their production.

"Back then was a tough financial time" for such firms—his clients—said Quander, an attorney and partner in the Billings office of the law firm Holland & Hart LLP. But as a major proponent for electricity deregulation in Montana in the 1990s, Quander and his large industrial clients have survived to see what they believe are the fruits of that effort.

"Since then the (electricity) market has been pretty good. There are not as many producers as we would like, but there are enough to keep rates competitive. ... My clients are getting rates that are quite a bit better than the default supplier, usually five to 10 percent less over the last several years," Quander said.

Electricity deregulation came to Montana in 1997 via legislative decree, with the expectation of offering residential, commercial and industrial energy users greater choice in providers. In essence, it allowed all energy customers the opportunity to buy power from whomever they liked; in return, utilities could market their services to customers previously off-limits in a regulated environment where customers were determined by service territory. What has evolved since then falls well short of that free-market goal and continues to be controversial.

Sounds good—does it taste good too?

The Montana electricity market is served by three groups of utilities: Investor-owned utilities provide power to more than half the state's customers, mostly in urban areas; rural electric co-ops serve many small communities throughout the state; and MDU Resources Group, based in Bismarck, N.D., serves an eastern slice of the state.

When the state Legislature deregulated the electricity market, it set slightly different rules for these three groups of providers. It exempted MDU altogether from deregulation because it served multiple other states, none of which was deregulating its power markets. Investor-owned utilities were (and still are) required to offer so-called choice programs that allow customers the chance to migrate among other participating utilities.

Co-ops were allowed to voluntarily opt in to choice programs and were given reciprocity to return to the traditional arrangement if they so chose. Dave Wheelihan, chief executive officer of the

Great Falls-based Montana Electric Cooperatives' Association, said two of his 26 members attempted to sell into the deregulated market but found little interest among businesses and residences, and returned to their original market arrangement as provided by law.

So, in essence, electricity deregulation in Montana today affects only those customers who get their power from an investor-owned utility, like the former Montana Power, most of whose customers are now served by NorthWestern Energy (more on that in a bit). Even here, however, not a whole lot has changed. Customers preferring to eschew other electricity providers can simply stay with the incumbent utility (technically called the default supplier), or the utility that typically provided power to a region prior to deregulation, and whose rates continue to be regulated by the state's Public Service Commission. Customers can also try the open market and then return to the default supplier at regulated rates when they choose.

So while the theory of deregulation is seductive—expanded choice leads to greater competition, which leads to lower prices—the reality has been something different, at least so far. Fewer than 1 percent of electricity customers in the state have switched providers, according to the PSC, and virtually all of them are large industrial firms that have the leverage to negotiate competitive price contracts with multiple providers. Virtually all residential and commercial business customers remain with the default supplier and pay regulated (though increasing) rates for electricity.

Even the state's industrial giants had some early doubts when, several years into deregulation, short-term contract rates for these users went from around $22 a megawatt hour to $200 and upward. After prices returned to earth in 2002, Quander began to see deregulation working, perhaps not precisely as he had wanted but still providing a competitive advantage for his clients.

What about the little people?

Quander is among the few who believe deregulation worked in Montana, and his optimism is tempered by the lack of competition that small-business and residential users find in the marketplace. Eight years after energy deregulation became law, the issue remains a sensitive one in Montana, where even politicians who initially led the charge have come to disown their actions. One former Republican Party leader, John Harp, offered a public apology last year for his role in deregulation and now serves as chairman of the creditor's committee in a lawsuit against the New York investment bank Goldman Sachs, seen as an instigator of the debacle.

Other casualties are aplenty. The state's only Fortune 500 company, once-mighty Montana Power, dropped out of energy production at the urging of its adviser, Goldman Sachs, to build a fiber-optic telecommunications company that came to be called Touch America Holdings Inc. In the aftermath of the Internet and telecom implosion, the company died a noisy and well-publicized death more than a year ago while Goldman Sachs walked away with close to $20 million in fees. Thousands of Montanans who put their retirement holdings into Montana Power and stayed the course were left with nothing.

Many of the story lines that come out of this deregulation controversy have their start in the Montana Power saga. The current default energy supplier, NorthWestern Energy, holds that role at the behest of the state Legislature even though NorthWestern generates little power itself. A transmission company, NorthWestern bought the state's power lines from Montana Power when that company spun off its energy business. As a result, NorthWestern buys power wholesale and then resells it to end users. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2003 after several big investments in other lines of business failed to pan out. It has crawled out of bankruptcy and recently rejected an unsolicited offer from a coalition of western Montana's five largest cities to buy the company in an effort to stabilize energy prices.

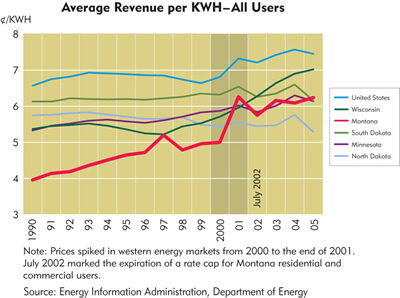

Most of the power sold by NorthWestern comes from PPL Montana, a Billings-based subsidiary of PPL (Pennsylvania Power & Light) Generation of Allentown, Penn., which bought Montana Power's generation assets and is now the lead supplier of power, directly and indirectly, for much of the state's more urban areas. PPL Montana was not designated as a default supplier because it does not sell power retail, only wholesale. So former Montana Power customers continue to get their power from the same generation and transmission assets. But they have seen prices for the same service rise considerably after a deregulatory grace period (which froze electricity rates for four years) expired in July of 2002.

As a result, the same state that voted overwhelmingly for George W. Bush turned simultaneously blue at the state level in 2004 when a Republican-controlled Legislature and governor's office turned over to Democratic control, in part a backlash against a Republican-led push for deregulation. And the Big Sky state, never one to attract much attention, found itself the subject of the legendary CBS news program "60 Minutes" in 2002.

No other state in the Ninth District has decided to deregulate its energy markets, although Michigan has entertained the notion. As such, Montana has become a case study of sorts for other states intrigued—or appalled—by the notion of electricity deregulation.

Advocates of deregulation say big users now have more power sources to choose from, better deals and a more vibrant market. They argue that the fate of Montana Power and its subsequent failure had little to do with deregulation and much to do with bets on telecommunications that simply proved horribly wrong.

Critics wonder if the whole transformation was worth the effort considering the mess it created and the lack of real savings, even for large businesses. And almost no one believes Montana consumers benefited much from deregulation. If anything, their rates may be higher today than they would be in the regulated environment found in neighboring states, critics charge. They point to federal government statistics from 1997 that show Montana's utility rates for different users were among the lowest in the nation; today, rates for all user groups in Montana are still lower than the national average, but have been creeping up and are closer to the middle than front of the pack in terms of affordability (see chart).

Still, markets are constantly evolving, and some argue that the book can't yet be closed on the utility of deregulation; some say proposals for new power plants are evidence of the market responding to deregulation by bringing more supply—and therefore choice—online.

Power hogs

To Quander, the rough start deregulation endured has nonetheless left his clients in good shape today. He leads an ad hoc group called the "Large Montana Customer Group," with members such as the

Smurfit-Stone Container Group, Montana Refining Company, Stillwater Mining Company, Advanced Silicon Materials LLC and others. Around 60 percent buy from PPL Montana; the rest from independent suppliers around the state and region.

Only a handful of companies in the customer group buy from NorthWestern Energy, the default provider. Since 2001, large users "have been able to contract to get power, and it's been reliable for prices at or below those offered by the default supplier," Quander said. "Generally, they feel comfortable with how the market is going and if given the opportunity would not return to the regulated market."

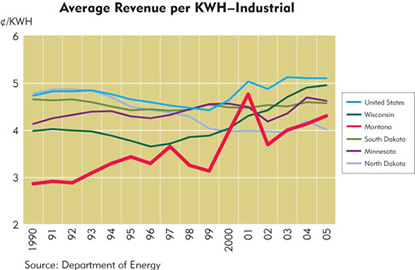

Despite Quander's endorsement of deregulation, Department of Energy data show that Montana's average electrical rates for industrial users have eroded somewhat compared to 1997, when it boasted the lowest industrial rate in the country at 3.66 cents per kilowatt hour.

Thomas Power, chair of the economics department at the University of Montana and vociferous critic of deregulation, said even if you agree that large users get a great deal under deregulation, those companies play a much less important role in the state than they did in the 1990s. More importantly, growth areas such as technology and service have seen no great decrease in their energy bills, said Power, even though they drive employment and wage gains in the state.

Before deregulation, energy costs for residential and business users in Montana compared very favorably to those in other district states and nationwide. But since then, average costs for these users have steadily crept up and likely more so than they would have had deregulation never occurred, Power argued. On the industrial side, he said that PPL Montana simply "cherry picks" large users that have significant 24/7 energy demands, since they can be served more easily and cheaply than smaller companies. As a result, a real marketplace only exists for a small number of large companies, said Power. The advocates "believed there was an infinite supply of energy just waiting to be liberated by deregulation," said Power. "That just didn't happen."

Tough baby steps to market

John Hines, director of energy supply for NorthWestern Energy, said about 65 percent of NorthWestern's electrical needs in Montana are purchased from PPL Montana; the rest from state-owned and privately owned sources. The company has had public spats over PPL's wholesale rates, yet remains a major customer since so few other suppliers have the power generation necessary to serve NorthWestern's clients.

"Part of the concept of deregulation is valid, and remains valid," he argued. "The larger customers have the authority to enter into contracts on their own, and they have. There are enough energy suppliers to make it worth it to buyers to devote time and energy to developing good energy deals."

PPL Montana sees more competition when offering contracts to NorthWestern, too, a clear sign a market exists, said David Hoffman, manager of external affairs for the company. NorthWestern recently asked for bids to buy electricity in the future and received 44 bids, he said. The first PPL Montana proposal was rejected by NorthWestern, said Hoffman, owing to the huge response by independent power companies. "Clearly there's a market available to supply what (NorthWestern) needs," he said.

Greg Jergeson, chair of the Public Service Commission, begged to differ. "I don't believe it's a competitive market," he said. "What we have is NorthWestern as our default supplier delivering electricity when a customer turns a switch on, and it's Pennsylvania Power & Light who is selling 60 to 70 percent of the available supplies."

As a member of the Senate during the deregulation debate, Jergeson joined 15 other members in voting against it because "it didn't make any sense to me." As the head of the PSC, an elected body, he has watched medium-sized companies "migrating back to the default supplier" after finding out other suppliers were more expensive, he said.But Ron Perry believed that allowing customers to migrate back to the default supplier represents the free market in play. Perry, chief executive officer and president of Commercial Energy of East Cut Bank, Mont., recently notified clients he could come nowhere near to matching NorthWestern's rates, and he watched 200 small- to medium-sized companies head back to the default supplier.

Still, as one of the behind-the-scenes architects of deregulation in Montana, Perry said the system worked. From 1998 to 2004, his clients "saved some money and were well served by us," he said. "But now I'm more expensive than the default supplier. My clients said, 'Hey, I'll pay a dollar more per megawatt hour to stay with you.' But I had to tell them they'd have to pay a lot more than that."Perry's confident a few years down the road the situation will change, and he may lure clients back. He could have cut the same deal as NorthWestern did a few years back with PPL Montana but chose not to, and now his per megawatt charge is substantially higher than the NorthWestern rate. That's deregulation working, not failing, he contended. Deregulation introduced market forces such as peak-based pricing and the concept that clients with 24/7 operations should pay less per megawatt hour than smaller firms that require power on only eight or nine hours a day, he said. By making clients sensitive to when they use electricity, conservation increased and usage changed to create more efficiency and lower bills, he claimed. In a deregulated climate, if utilities build an unnecessary plant or make an unwise investment, shareholders pay, as they should.

Residential: What about us?

But not even Perry believed competition had come to residential markets, or that homeowners would have much of an appetite for entertaining a mailbox full of offers from a variety of producers. Nor has there been much clamoring for the state's Public Service Commission to end its practice of regulating the rates of default suppliers. The Republican Party, a major supporter of deregulation, has little confidence Montanans will ever see competition at the residential level.

"I would say, no, we're not in a market where choice exists (for residential customers), and that was the primary objective of deregulation," said Chuck Denowh, executive director of the Republican Party of Montana. "There's a lot of perceived problems with deregulation, and as a result there's been a lot of negatives associated with it."

NorthWestern's Hines pointed out that even under the best of circumstances—a perfect open market—consumers in Montana might see a monthly savings of only 10 percent. Issues like low population density and costs for transmission and marketing services from the regulated system cannot be changed, he said, and they invariably decrease the potential savings.

Consumers would also fear the "hassle" factor of moving to another carrier, Hines said. Losing long distance or phone service for a day is tolerable compared to losing heat and light. "Electricity is a lot more important a service than a phone, and it's very complicated to do," he said. "There's a lot of upside risk and very little positive benefit you get with it."

Even Quander doesn't argue with the paltry benefits seen by state consumers. Though residential customers were shielded from the spike in western utility rates in 2000 and 2001 due to a four-year legislative cap on rates, many Montanans worked for firms that closed or reduced work hours during that time, said Quander—an experience they took home with them. As a result, he sees no great interest among power companies to compete for consumers, nor much in the way of potential savings, either.

"Even though Montanans never saw the impact of any of the energy crisis, it scared the heck out of everybody," he said. "No one has an appetite for that again anytime soon. The transactional and administrative costs would be more than the modest savings you would see."

Don Sharp, public relations manager for MDU Resources, almost laughs at the prospect of anyone coming into eastern Montana to compete with MDU. The largest city has only 8,000 inhabitants, and most of the towns, "if they're not holding their own they're drying up," he said. "Everyone will tell you deregulation has been a failure. The idea was to inject competition into the electrical utility market and bring down prices, and the competition just never materialized, nor did the goal of cheaper utility rates."

A circuitous road

Still, nor does Montana appear eager to reregulate its utilities, probably in part because that strategy is no panacea either. One need only look to Wisconsin, a state that has not deregulated and has experienced steeper increases in electricity prices since 1997 than Montana. Requests for rate increases have been rampant among that state's energy providers. WE Energies, for example, is seeking a 6.9 percent increase on Jan. 1. The request comes on top of approval for three rate hikes over the past 12 months, which have already added about 10 percent to the average residential electric bill.Indeed, markets don't always react at the flick of a switch, if you will, and some argue that deregulated electricity markets are still evolving. Quander believed that as more plants in Montana come online—a wind plant in Judith Gap and a new plant in Hardin, to name just two—competition and potentially lower electric rates might result, he suggested.

Those plants and several more on the drawing board would never have been built without deregulation, according to Perry, from Commercial Energy. With the opportunity to sell power to big energy companies, large business users and the state's many power co-ops, companies believe it's worth the risk to build new plants.

Since opening an office in Oakland, Calif., to sell natural gas transported by pipeline from Montana, Perry looks at California's odyssey in deregulation as having the same silver lining as Montana's. "Without dereg in California there would be blackouts all the time," he said. "After deregulation, the markets here have responded with a lot of new plants coming online."

So despite the controversy and low opinions of deregulation, the state's energy community and regulators appear to be willing—if sometimes grudgingly so—to ride out deregulation for the near future to see where this policy circuit might take them.