Over the last half century, the World Bank, various U.N. agencies and a host of nongovernmental organizations have made heroic efforts to combat hunger, treat and prevent disease, promote literacy and stimulate economic development. Hundreds of billions of dollars, much in the form of voluntary charitable contributions, have been

spent on a vast array of projects. One wonders why, after so much well-intentioned time, effort and money have been expended, more has not been accomplished.

Over the last half century, the World Bank, various U.N. agencies and a host of nongovernmental organizations have made heroic efforts to combat hunger, treat and prevent disease, promote literacy and stimulate economic development. Hundreds of billions of dollars, much in the form of voluntary charitable contributions, have been

spent on a vast array of projects. One wonders why, after so much well-intentioned time, effort and money have been expended, more has not been accomplished.

At least, one might suppose, earlier experiences would inform subsequent efforts, prompting donors to direct resources toward projects that have a substantial chance for success and would produce large benefits relative to their costs. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Some of the donor agencies surely have political agendas as well, so other motives come into play. But many do not, and even in these quarters the idea of systematically evaluating alternative projects is sometimes viewed as heretical. It is as if a careful examination of evidence, with the potential for concluding that some types of projects are less successful than others, is simply unacceptable. Charitable endeavors are like the children of Lake Wobegon: They are all above average.

The Copenhagen Consensus project was conceived to challenge that taboo head on, with the classic method of benefit/cost analysis as its major weapon. The project was framed in terms of the following question: If one had $50 billion to spend over the next five years to make the world a better place, what would be the best way to use it? The Copenhagen Consensus did not itself have funds to allocate. Instead, its goal was methodological—to demonstrate that alternative projects could be prioritized. The objective was to show that a group of economists, informed by experts in various areas and using the tools of benefit/cost analysis, could compare potential uses for funds and, at least to some extent, rank them in a way that reflected economic reasoning. Consensus would be success: If the expert opinions at the end displayed considerable agreement, that agreement could be interpreted as a reflection of economic science.

Before proceeding, it may be useful to describe the basic idea behind benefit/cost analysis. Briefly, the method involves comparing the total value of the benefits (B) the project produces with its total cost (C). If the benefits fall short of the costs (B < C), then the ratio B/C is less than one. In this case, the project should not be undertaken. If the benefits exceed the costs (B > C), then the ratio B/C exceeds one, and the project is worthwhile if there are no financing constraints. Notice that the ratio B/C measures the value of the benefits per dollar of expenditure, so projects with higher B/C ratios provide more "bang for the buck." Thus, if the budget is limited and many projects are competing for funds, the B/C ratios can be used to rank them. Those with higher ratios should get priority.

For example, suppose there are five potential projects: A, B, C, D and E, each with a cost of $10 million and benefits of $120, $8, $200, $30 and $90 million, respectively. Then their B/C ratios are 12, 0.8, 20, 3 and 9. Project B has a B/C ratio below unity and should be dropped from consideration. The others can be ranked: C, A, E, D. If the available budget is $10 million, then project C should be funded; if it is $20 million, then both C and A should be funded, and so on.

Costs and returns that accrue in later years must be appropriately discounted (more on this below), and the accounting must be complete—managers' time, interest costs, effects on other projects and so on must be included. Although the basic concept is straightforward, implementing it is not always easy. For many public-sector projects, the returns are goods or services or outcomes that are not priced in the market. In this case, the economist must try to impute shadow prices to the outcomes.

Benefit/cost analysis is an imperfect tool. Implementing it typically requires making assumptions, taking shortcuts and omitting some important factors. Nevertheless, it provides a useful framework for comparing projects, allowing us to organize the quantitative evidence within a systematic framework. Even if the final B/C ratio does not tell the whole story, the assumptions used to construct that ratio must be made explicit, the omissions and shortcuts are exposed, and the issues being left out can be identified and discussed in parallel with the quantitative analysis.

Above all, it dispels the notion that a $15 billion health care project simply cannot be compared with a $10 billion project to provide irrigation or a $12 billion project to finance schools. They can be compared. Honest, intelligent people may still disagree at the end, but the discussion is improved by making the comparison more orderly.

The stated goal of the Copenhagen Consensus was to identify the best ways to spend $50 billion. This meant coming up with a list of specific projects, ranked from highest to lowest in terms of their B/C ratios, and providing justification for the ranking. This process necessarily identifies some projects as having B/C ratios that exceed one but are too low to justify funding given the budget constraint. It may also conclude that some projects have costs that exceed their benefits.

The first step was to identify broad areas with problems that are important and that might offer opportunities for useful action. A very long initial list of global problems was assembled. The panel of economists then narrowed that list to 10 Challenges: climate change, communicable diseases, civil conflict, access to education, financial instability, governance and corruption, malnutrition and hunger, migration, sanitation and access to clean water, and subsidies and trade barriers.

For each Challenge, a specialist was commissioned to write a paper identifying several specific proposals for useful intervention, and two additional specialists were commissioned to prepare comments. The panel of economists read the 10 papers and 20 comments, and then met for a week to hear presentations from the 30 specialists.

Overall, the Challenge papers were excellent, as were the comments. The experts were well chosen, and they took their assignments seriously. The proposals were diverse, and the discussions they provoked during the panel's week in Copenhagen were wide ranging, stimulating and informative. The schedule was tight, a three-hour session in the morning and another in the afternoon, for five hectic days, writing up notes and making calculations during lunch and at the end of each day. The discussions ranged far and wide, including digressions on demography, medicine, history, politics, institutional change and other topics. It's a pity that a hidden tape recorder wasn't taking it all down. Anyone who fears that a group of economists doing benefit/cost analysis will not take their eyes off the numbers long enough to consider the whole picture should rest easy. Economists like numbers, but we seem to enjoy even more a spirited debate of the issues surrounding the numbers.

The discussions and debates notwithstanding, in the end the individual and group rankings did show considerable agreement. For example, there was a strong consensus about the four top-ranked proposals: to control HIV/AIDS, to provide micronutrients where deficiencies exist, to liberalize world trade and to control malaria. Three of these proposals were targeted directly at saving lives and improving health. There was also strong consensus about the bottom-ranked proposals, which involved emissions abatement. These proposals involved extremely costly measures in the near term and produced benefits in the distant future.

The top- and bottom-ranked proposals reflect two general issues that arose in calculating cost and benefit figures: choosing a discount rate and valuing lives. The discount rate was the easier task. It is an issue that arises in evaluating any type of investment project. The basic idea is simple: $100 in the future is not the same as $100 right now, with the difference depending on the interest rate. For example, if $100 is invested at an interest rate of 5 percent, in three years it is worth $100 x 1.05 x 1.05 x 1.05 = $115.76. By the same token, a claim to $100 three years from now is worth only $100/(1.05 x 1.05 x 1.05) = $86.38 today.

Consequently, if a project has costs and benefits that arrive over a number of years, those values must be appropriately discounted to make them comparable to each other. If all of the costs and benefits accrue within a fairly short time span, the choice of the discount factor is not terribly important, but if the benefits arrive in the distant future, the discount factor is critical. An example illustrates why this is so. Suppose a project has a cost of $100, paid in the first year, and produces benefits of $100 per year in each of the next five years. At discount rates of 0 percent, 2 percent and 5 percent, the resulting B/C ratios are 5, 4.7 and 4.3. If the benefits arrive after 100 years, the ratios are 5, 0.62 and 0.025. In the first case, the B/C ratios are different, but in the second, they are wildly different. At a discount rate of 0 percent, the ratio exceeds one and the project looks appealing. At discount rates of 2 percent and 5 percent, the ratio falls below one, indicating that the costs exceed the benefits and the project should not be undertaken.

Most of the panel members, including me, adopted a 5 percent discount rate. It is a reasonable figure, falling within the range of various market interest rates, and it had the practical advantage of being the one used in most of the proposals.

The problem of valuing lives was a harder one. Many of the projects involved measures to save lives or, to use the technical term, avert premature deaths. To compare these projects with each other and with projects involving other types of benefits, the panel needed to choose a consistent method for valuing lives or life-years. Many of the Challenge paper authors valued life-years using average annual per capita income in the relevant country or region, usually around $1,000. This approach sets the value of a life at the value of the economic goods and services that person produces or consumes. The panel of economists quickly agreed that this figure was far too low. A principle suggested by one panel member was adopted instead, to value a life as the individual would value it. To arrive at a figure, one estimates how much people are willing to spend, out of their own pockets, to reduce the risk of accidental death. For example, people are willing to pay more for cars with airbags and other protective features. Although estimates of this willingness to pay are imprecise, evidence from developed countries suggests that individuals value life-years at around five times annual per capita income. For an annual income of $1,000 and a discount rate of 5 percent, this leads to a figure of approximately 5 x $1,000/.05 = $100,000 for the value of a life saved.

Since the goal was to show that projects can be prioritized in a meaningful way, it is illuminating to look at the whole range of proposals considered and to examine some of the cost and benefit figures put forward by the authors. These figures vary greatly in terms of reliability, with some based on extensive previous research and others put together for this project on the basis of available information. All of the figures should be viewed as rough estimates. In some cases, too little quantitative information was available, and no B/C ratios were offered. The next section describes the proposals and reports the B/C ratios calculated by the authors. The final rankings are then discussed in more detail.

The Challenges

Climate change Global warming is an important issue for the developing world as well as the developed one. Estimates of the eventual losses if nothing is done are in the range of 0.75-1.0 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for the United States, but the effects could be catastrophic in some developing countries, especially those in warm, dry regions. Agricultural areas in Africa and Asia that are marginal now could become true disasters. And while the economic losses in the developed world may be larger in absolute value, the poorer regions of the world will be less able to cope with declines in income.

Evidence is building that human activity alters the climate, that it is noticeable already and that it will worsen over the next century or two. But while there is widespread agreement among scientists that higher levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere trap heat, the quantitative relationship is still uncertain. The effect of doubling the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases is thought to be an increase in global temperature of around 1.5-4.5 degrees C, but it could be higher. The economic effects are unlikely to be substantial in the near term, however. Even the author of the Challenge paper, a strong advocate of immediate action, noted that the standard time horizon for calculating the economic consequences of rising temperatures is at least one century.

Three proposals were put forward: a global emissions tax; implementation of the Kyoto protocol, which allocates an emissions "quota" to each developed country (although it leaves developing countries, including China and India, unrestricted); and a policy similar to Kyoto in structure but with much lower quotas. The third proposal was based on a pessimistic forecast about the climate consequences of doubling the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases: a temperature increase of 9.3 degrees C instead of 1.5-4.5 degrees C.

All three proposals entailed extremely high costs in the near term and benefits arriving after a century or more. Thus, the key issue for this Challenge was the choice of a discount rate. At a discount rate of 0 percent, the number favored by the author, the three proposals had B/C ratios of 2.1, 1.8 and 3.8. At a discount rate of 3 percent, also reported in his paper, the ratios were 0.3, 0.2 and 0.3. At a 5 percent discount rate, the ratios would have been even lower: All of the proposals had costs exceeding benefits by wide margins. The panel's overall conclusion was that climate change is a problem and it should not be ignored, but given current technology, reducing emissions drastically over the next few years is far too costly relative to the benefits it would produce.

In addition to the proposals offered by the Challenge paper, the panel discussed research and development to improve the science about links between greenhouse gases and climate, to improve technologies for reducing emissions and to develop alternative ways to reduce the climate effects of greenhouse gases. The notion of a small tax was also discussed, one designed to raise public awareness and to start building institutions to coordinate international efforts to reduce greenhouse gases.

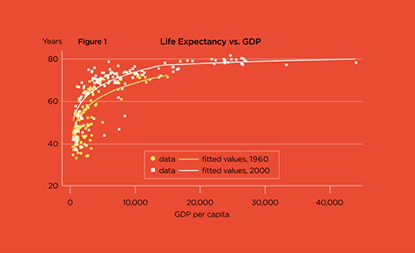

Communicable diseases Enormous strides were made in improving health during the 20th century, in poor countries as well as rich ones. Nevertheless, poor countries still have significantly higher mortality rates. Both of these facts are displayed in Figure 1 (right), which plots life expectancy at birth against per capita GDP for about 100 countries, for 1962 and 2002. In each year, life expectancy increases with income per capita, especially at low income levels. In addition, it rises significantly at every income level over the four-decade period. For most countries, improvements in life expectancy came from both factors. Higher incomes led to better nutrition and health care and, in addition, technological improvements in health care—better vaccines and better treatments for infectious diseases—improved survival rates even at constant income levels.

In low-income countries, much of the improvement came from reductions in the mortality rate for children under five, but in some regions, the mortality rate for this group remains high. As Table 1 (below) shows, three communicable diseases are among the leading causes of death in children in developing countries: malaria, measles and HIV/AIDS. (Diarrhea is also an important problem, but the most important weapon against it is access to clean water. A proposal along these lines is put forward in the Challenge paper on sanitation and water.)

Table 1 Leading causes of death in |

||

Cause |

Number |

% of all |

Perinatal conditions |

2,375 |

23.1 |

Lower respiratory conditions |

1,856 |

18.1 |

Diarrheal diseases |

1,566 |

15.2 |

Malaria |

1,098 |

10.7 |

Measles |

551 |

5.4 |

Congenital abnormalities |

386 |

3.8 |

HIV/AIDS |

370 |

3.6 |

Pertussis |

301 |

2.9 |

Tetanus |

185 |

1.8 |

Protein-energy malnutrition |

138 |

1.3 |

Other causes |

1,437 |

14.0 |

Total |

10,263 |

100.0 |

Source: Lomborg (2004, Table 2.1) |

||

Additionally, in some countries of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the arrival of HIV/AIDS, the appearance of resistant strains of tuberculosis and a resurgence of malaria have eroded much or all of the earlier gains in life expectancy.

Three proposals were put forward: for control of malaria, for control of HIV/AIDS and for strengthening basic health services. These proposals illustrate the range of opportunities available for reducing mortality and improving health. Malaria affects people of all ages but is an important cause of death mainly for young children. HIV/AIDS affects adults of working age, so an important part of its cost is the loss of a wage earner suffered by the family. Improving basic health services—community health centers, clinics and local hospitals—has broad benefits. Health centers provide important services for vulnerable groups like pregnant women, infants and young children, and they also provide the infrastructure needed to implement disease-specific programs like the malaria and HIV/AIDS initiatives.

It is difficult to measure the cost of illness with precision. In poor countries, many health costs must be paid out of pocket. The income of the ill individual is lost, and additional income is lost from time required by family and friends to care for the ill individual. Thus, the value of saving a life is a conservative estimate of the benefit from intervention.

Efforts during the last century were effective in eliminating malaria from large parts of the world, but more recently the situation has stagnated or worsened. The earlier gains were made in regions where control—often by draining swamps and eradicating mosquitoes—was easier. In the areas where malaria remains, mainly SSA, those measures are impractical. The problem has also become more difficult as the Anopheles mosquito has developed resistance to older insecticides and the malaria parasite has become resistant to earlier drug therapies.

Typically, people in malarial regions are infected when they are young. If they survive into adulthood, the parasite remains in their bodies, causing periodic episodes of illness. These episodes are not usually fatal for adults, but they are incapacitating.

SSA has 90 percent of remaining malaria cases, and in that region malaria causes 20 percent of deaths in children under five. A recent and highly successful program in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa served as a model for the proposal here. The program has three parts: provision of insecticide-treated bed nets, treatment for pregnant women and the use of a combination drug therapy (ACT) to treat symptoms in adults. Bed nets are especially important for young children, for whom malaria is often fatal. Treatment of pregnant women is useful because of the vulnerability of the unborn child. And ACT drug therapy, while more expensive than the older drugs, is much more effective in controlling symptoms when they occur. The reported B/C ratio for the entire package of malaria control measures was 39, but this figure valued life-years using per capita income.

HIV/AIDS was the cause of around 3 million deaths in 2003. About 40 million people were infected at that time, and there are about 5 million new infections per year, the vast majority in developing countries. And unless action is taken soon, infection rates will surely rise. The cost of prevention is much lower than the cost of treatment, and prevention itself is less costly if it is undertaken before infection rates explode in the general population.

Infection rates are not well measured, but they are very high, over 5 percent, in southern and eastern Africa and in a few countries in West Africa. In some areas, rates are perhaps as high as 40 percent. A large proportion of transmission is in the sex industry, and the highly successful 100 percent condom program in Thailand is a model for reducing that channel of transmission.

The HIV/AIDS proposal involved condoms and treatments for sexually transmitted diseases for sex workers, female condoms for a much broader group, programs for blood safety and prevention of mother-to-child transmission. The cost for these various initiatives was about $6 billion per year over five years, and the benefit would be to avert about 2.5 million new infections per year. The authors estimate the B/C ratio for the entire package to be 43.

The benefits from expanding basic health services are particularly hard to quantify. Local clinics and hospitals can provide inoculations and vitamin supplements, as well as primary medical care. They also facilitate the delivery of specific interventions like the malaria and HIV/AIDS programs just discussed. In regions that lack a network of basic health services, delivery of other programs may be impossible. The B/C ratios were estimated to be in the range of 2.5-5.8.

Civil conflict Wars are very costly. In addition to the direct financial burden and loss of life, they also exact large tolls in other dimensions. Displaced civilians who lack adequate food, shelter and clean water suffer high rates of disease and increased mortality. Investment is deterred, retarding growth. And the social fabric is torn in other areas as well: Education suffers, infrastructure deteriorates and so on. In recent decades, civil wars have been the most common type of conflict, and they were the focus of the proposals here.

Civil wars have consequences that radiate like ripples in a pond, affecting neighboring countries as well as the nation at war. Regional costs include economic consequences from reduced trade, and social and health costs from the inflow of refugees. In addition, high military spending in a country suffering a civil war often makes its neighbors feel less secure and leads them to raise their own military spending as well. The resulting "neighborhood arms race" siphons off resources and increases the risk of across-border conflict. A rough estimate is that total regional costs may be two or three times the annual GDP of the country with the civil war. Global costs include the fact that war-torn countries can provide safe havens for illegal drugs or terrorists.

Three broad categories of intervention were considered: to prevent conflicts, to shorten their duration and to reduce the risk of relapse in situations where conflict has ceased. Of the three, the last seemed to offer the most promising prospects for intervention.

The risk of relapse is high after a conflict has ended, and it remains high for a decade. Half of all civil wars are relapses that occur within the first decade after the last war ended, and typically there are about 12 countries in this one-decade window. Outside military intervention is an attractive option for reducing the risk of relapse.

After a conflict ends, an important concern is maintaining stability. One way to do this, or at least one way that appears attractive, is with a strong military. But high military spending in this situation raises the probability of relapse, suggesting that there is a useful role for outside peace-keepers. A successful example is the British intervention in Sierra Leone in 2000, after the end of the civil war. The British force was brought in at the request of the government, and it was effective in establishing and maintaining peace. The cost was quite modest, $50 million per year.

One specific opportunity with promise is to promote greater transparency and better tracking in resource markets. An international agreement that involves certification to the purchaser that rough diamonds are from a legitimate source has almost eliminated the market for "conflict diamonds." In earlier years, profits from these diamonds had financed rebel movements and contributed to devastating civil conflicts in Angola, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone. Similar tracking in other markets might reduce the funds available to potential combatants.

Access to education Large urban school districts in the United States have found it difficult to raise the quality of education at failing schools. The public school systems in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and elsewhere have struggled to reduce dropout rates and raise achievement. Schools in developing countries also face these problems, and others as well.

Table 2 (below) displays primary school enrollment rates for various groups of countries, sorted by average income (top panel) and geography (bottom panel). As the top panel shows, even for low-income countries, the average enrollment rate is fairly high. But as the bottom panel shows, the average masks very low rates in certain regions, notably SSA and South Asia. In addition, enrollment rates for girls are substantially lower than those for boys in a number of countries.

Table 2 Primary school enrollment |

|

Enrollment rate (net) |

|

Low income |

85 |

Middle income |

88 |

High income |

95 |

|

|

SSA |

56 |

South Asia |

83 |

Middle East/North Africa |

84 |

East Asia |

93 |

Latin America |

97 |

East Europe/FSU |

88 |

OECD |

97 |

Source: Lomborg (2004, Table 4.1) |

|

In some places, physical expansion of facilities is needed: The closest school is too far away to be easily accessible. Instructional material—paper, pencils, books and chalk—are woefully lacking in some places, and teachers are often poorly trained and poorly motivated. But in most places, the more important problems are that children never enroll at available schools, they enroll but drop out too soon or they attend but fail to achieve. Thus, improving quality is more important than expanding scope.

The author of the Challenge paper offered only one serious proposal, a call for "systemic reform." His view was that extensive research on the relationship between expenditures and student achievement has been unable to establish a close link. Thus, absent more fundamental reforms, increasing spending levels may do nothing to improve performance. In a general sense, lack of accountability is the underlying problem.

But "systemic reform" and "increased accountability" are not easy to define or implement even in the United States, in settings with well-functioning, well-intentioned local and state governments. In developing countries, the situation is even bleaker. Can anything be done within the current (very poor) institutional environment in those countries?

The panel members and discussants were more optimistic than the Challenge paper author. One interesting proposal was offered by a discussant. School fees are common in many developing countries, and though they seem low by developed-country standards, for poor households they are prohibitive. School fees were eliminated in Malawi in 1994 and in Uganda in 1997, and in both places, school enrollment and attendance rose quickly and substantially.

A back-of-the-envelope benefit/cost calculation was made for the program in Uganda. The median cost of primary education in SSA is $45 per pupil per year. (The figure for Uganda is much lower.) One major benefit from higher educational attainment is the increased lifetime earning of the individual. Psacharopoulos and Patrinos (2004) estimate that for SSA as a whole, the average rate of return to each additional year of primary education is 11.7 percent. (The estimate for Uganda is actually higher.) Using per capita income figures for SSA, this implies that an additional year of schooling raises income by $64 per year. Thus, for an interest rate of 5 percent and a working lifetime of 25 years, it raises the present value of lifetime earnings by $900. (Using per capita income in Uganda would almost double this figure.) Thus, a conservative estimate of the B/C ratio from eliminating primary school fees in Uganda is 900/45 = 20.

Other evidence confirms that school attendance responds to economic incentives. For example, Miguel and Kremer (2004) found that an experimental program in Kenya offering meals and a deworming program raised attendance, and Schultz (2004) concluded that the Progresa program in Mexico, which offered modest cash incentives, was effective in persuading families to keep their children in school.

Financial instability Financial crises are not typically a problem in low-income countries, where financial markets are too poorly developed—and in some places repressed altogether—to permit crises. Instead, financial instability is, for the most part, a problem of middle-income countries like Argentina, Bolivia, Mexico, Korea, Thailand and Indonesia.

What are the sources of these crises? Unsustainable fiscal policy is one. Governments that routinely spend more than they collect in tax receipts must borrow to cover the deficit. As their debt accumulates, the pressure to escape it grows as well, and they become susceptible to mounting investor skepticism about the government's ability or willingness eventually to repay. A financial crisis occurs when the government finds itself unable to roll over the outstanding debt at a tolerable interest rate.

Institutional weaknesses may also contribute. Balance sheet vulnerabilities in the banking sector, such as mismatches of assets and liabilities in terms of their maturity structure or the currency in which they are denominated, may contribute. Weak regulation of the banking sector and poor corporate governance may lead to excessive risk taking and increased vulnerability.

Most of these problems are not readily addressed by intervention from outside, however. The proposal offered by the Challenge paper author instead addressed the issue of "currency mismatch." Borrowers in emerging markets usually are forced to write contracts in hard currencies, such as U.S. dollars, euros, pounds sterling or yen. Consequently, exchange rate movements can wreak havoc on their financial position.

The proposal was to have the World Bank and other international financial institutions create a new set of financial instruments to address currency mismatch. These new instruments would consist of debt denominated in an inflation-indexed basket of emerging market currencies, an EM index. To create a "thick" market, the World Bank and the G-10 countries would issue EM-denominated debt as a substitute for issues that they would have made in hard currencies.

The cost of this proposal is the premium that investors would demand from these high-quality borrowers for debt denominated in the EM index rather than in dollars or other hard currencies. This premium would depend on the expected change in the exchange rate between the EM index and the dollar, the risk premium for holding EM-denominated debt and a premium for holding debt in a (presumably) less liquid market. The benefits for emerging-market borrowers would be the avoidance of currency mismatch and the consequent avoidance of financial crises. The author estimated the annual costs to be $0.5 billion and the benefits to be $107 billion, for a B/C ratio of 214.

The logic of this proposal is appealing, but nothing like this has ever been tried, and several questions arise. First, if the gains from creating this new financial instrument are large, why isn't it a good profit opportunity for the private sector? The proposal assumes that transaction costs and network externalities, the need for a "thick" market, are the key problems that prevent private parties from creating the missing markets. But similar transaction costs have not impeded private-market solutions in similar areas. For example, private markets have been the vehicle for the growing share of EM stocks in developed-country portfolios, without any encouragement from the outside.

In addition, any country can avoid the currency mismatch problem by simply dollarizing or euroizing on its own. The costs of doing so would be the forgone seigniorage and an inability to conduct monetary policy. If currency mismatch is an important source of financial crises, this route should be attractive to sovereign states, without any intervention. The fact that to date no country has taken this route suggests that currency mismatch may not be a major factor behind financial crises.

To the extent that the problem arises from poor government policy in EM countries, the new market instrument proposed here would not help much. Countries that find it difficult to borrow are often those that have a history of inflating away their debts or engaging in outright default, and financial engineering cannot help a government that lacks the ability or will to meet its debt obligations.

Governance and corruption According to researchers at the World Bank, bribery totals roughly $1 trillion per year worldwide. Moreover, outright bribery is only part of the broader problem of corruption and poor governance, and perhaps not even the largest part.

Clearly, there is no single solution to this problem. Five options were offered here: improving accountability at the grass-roots level, benchmarking cost estimates for public projects, simplifying tax systems and implementing incentive-based reform, streamlining business regulations, and increasing transparency in international contracts for natural resources and tracking assets of corrupt officials. (The last echoes one of the proposals on civil conflict.)

The benefits of improving governance are potentially large. For example, higher levels of corruption are associated with lower levels of investment and lower expenditures on education, so it is likely that poor institutions hamper growth. Nevertheless, it is not clear what tools are available to reduce corruption or strengthen weak institutions. Military intervention from the outside is an extreme option, very costly and with no guarantee of success. Revolution from the inside is sometimes the solution, and outsiders can provide financial and other assistance to internal reformers.

Less extreme measures may be of some use, but even the methods that work against pockets of corruption in a generally well-functioning government are unlikely to be effective when corruption is extreme and permeates the entire political system. The groups that benefit from bribes and corruption usually have considerable political power and resist change. Outsiders can advocate reform, calling for more accountability, enhanced transparency, tax reform, less red tape and so on. Doing so is inexpensive but probably not very effective. Providing cost benchmarks for public projects could be useful, and increasing transparency in international transactions involving natural resources may be worthwhile.

Malnutrition and hunger While the United States fights an epidemic of obesity, chronic hunger and malnutrition affect 800 million people worldwide. The costs of chronic malnutrition are large in terms of both financial losses and human suffering. Poorly nourished populations are less productive, more susceptible to infectious disease and more likely to suffer premature mortality. Although hungry people can be found around the globe, the problem is especially acute in Asia, with 500 million malnourished people, and in SSA, with 200 million.

Four proposals were offered: reducing the prevalence of low birth weight, promoting infant and child nutrition and exclusive breast-feeding, reducing deficiencies of micronutrients (iodine, vitamin A, iron and zinc) and investing in technology for developing-country agriculture.

Malnutrition often begins in utero. Low birth weight (LBW) babies suffer a plethora of problems, including higher mortality rates, increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, physical stunting and impaired cognitive development. Thus, maternal malnutrition is an important issue.

After birth, the first two or three years of life are also critical. More than half of child deaths in developing countries can be attributed, directly or indirectly, to poor nutrition. In addition, severe malnutrition early in life leads to lower activity levels, impaired cognitive development, poorer fine motor skills, slower learning and lower ultimate attainment in school.

The first two proposals address these problems. One involves interventions targeted at pregnant women: preventing and treating various microbial and parasitic diseases, providing iron/folate supplements and providing targeted food supplements. It also involves raising awareness of the effects of close birth spacing and early motherhood on the risk for LBW. The other involves improving information about the positive effects of breast-feeding and about complementary foods for young children. The B/C ratios for these projects were 4 and 3.

The third proposal addresses a somewhat different problem. Deficiencies in certain micronutrients have particularly severe effects, even if calorie intake is adequate. Iodine deficiency in pregnant women increases the risk of LBW and infant mortality. In infants, it affects development of the central nervous system and reduces cognitive ability. Iron deficiency in utero and in infants and young children also affects development of the brain. Vitamin A deficiency leads to higher risk of infant and child mortality and can lead to blindness at any age. Zinc deficiency results in slower physical growth, measured by either height or weight.

The proposal to reduce micronutrient deficiencies involved two approaches, provision of supplements and food-based programs. The latter includes fortifying foods already in the diet and promoting consumption of specific nutrient-rich foods. The overall B/C ratio was 36.

For iodine, fortifying table salt is a cheap and effective method that produces striking effects very rapidly. A program in China reduced the fraction of school children with iodine deficiency by 75 percent in five years. In regions where fortifying salt is impractical, an alternative is capsule distribution. This approach is much more expensive, but the high cost may be justified for targeted groups, like women in their childbearing years.

Vitamin A supplements are inexpensive and can be given in large doses. A program providing two doses per year is quite effective and costs about $1 per person per year when implemented as an add-on to an existing health program. Children can receive supplements at school. Fortification of flour, sugar, oil or margarine can also be effective, although fewer data are available for programs of this type. Fortification may be less costly, but its coverage may also be lower, since people may continue to buy unfortified products if they are available and cheaper.

Megadoses are not suitable for iron, so supplements must be given on a weekly or daily basis. For children, they can be provided at school. In an experimental program in Kenya, providing deworming medicine and daily supplements in school was effective in reducing iron deficiency anemia (and raising school attendance). For pregnant women, iron supplements can be implemented as an add-on to other programs targeted at that group. For the general population, the fact that daily doses are most effective means that fortification (of flour, rice or salt) is an attractive alternative. A program in Ethiopia that distributed iron cooking pots was also quite effective.

The fourth proposal was for investment to improve crop varieties, producing varieties with higher yields, higher levels of micronutrients, improved responsiveness to fertilizer and water, reduced need for pesticides, higher resistance to pests and drought or shorter time to maturity (to allow double or triple crops per year). Assessments of previous investments of this type, such as those that led to the green revolution and "golden rice," suggest that the returns on projects of this type are high. The B/C ratio was estimated to be 15.

Migration A total of 175 million people, about 3 percent of the world's population, live outside their country of birth. Although political and ethnic/religious persecution play some role, most migration is economically motivated: People move to improve their earning prospects. About 60 percent of migrants are found in the developed countries. Potential migrants face formidable barriers, however. Many destination countries tightly restrict legal migration and make illegal entry expensive or dangerous or both.

Three proposals were offered for managing migration. The first was a selective policy, designed to target "successful" migrants. The idea is that high-skill migrants are more easily assimilated and create less social tension. The models for this proposal are the policies in Canada and New Zealand, where potential immigrants are screened on the basis of education, language skills and other attributes. These policies have been successful in the sense that they have permitted a significant number of immigrants (around 220,000 per year in Canada, a country of 30 million people) while minimizing resistance among the native born.

The second was a guest worker policy, targeted toward unskilled workers. An important question with such programs is whether it is feasible—or desirable—to encourage short-term migration. In the past, many migrants of this type have eventually settled permanently, despite rules designed to make them temporary. Even if their temporary status could be enforced, it is not obviously better for either the migrant or the receiving society. Explicitly temporary workers have less incentive to develop language skills, bring families or otherwise become assimilated into their new environment, and the lack of assimilation may exacerbate social tension and political backlash.

A third proposal involved various special taxes and transfers with two goals in mind: to encourage workers on explicitly temporary visas to return home at the end of their stays and to redistribute some of the economic gains from migration to the sending countries. An expanded role for the state in managing the types of migrants, where they work and how long they stay creates problems of its own, however. An additional bureaucracy would be needed to collect special taxes on immigrants, and allocating those revenues would create political pressures.

What are the benefits and costs of lowering the barriers to migration, and how are they distributed across various interest groups? Clearly, the movers themselves benefit. Data for U.S. immigrants indicate that on average their earnings increase by 85 percent compared with the year before they move. Moreover, the probability of finding work and the proportionate wage gain conditional on employment are about the same at every educational level. In the receiving country, owners of capital also benefit, but native-born workers who must compete with the immigrants suffer. Both of these effects are reversed in the sending country.

If employed, immigrants pay taxes and add to social security contributions in the receiving countries. They also increase the demand on public schools and other social services, and they may strain the welfare system if too many are unemployed. The modern welfare state makes the cost high if immigrants fail to find jobs, and the extension of social welfare benefits may encourage jobless, welfare-dependent migrants. This group is exactly the one that creates social and political backlash. The problem is exacerbated if legal migrants face competition from (lower-wage) illegal migrants, and periodic amnesties encourage the latter.

The appropriate policies may differ across developed countries. U.S. labor markets are more flexible than those in Europe, and U.S. society is more open. Thus, the United States may be in a better position than Europe to admit immigrants of all types.

Sanitation and access to clean water At the turn of the millennium, 1.1 billion people worldwide lacked access to clean water and 2.4 billion lacked access to basic sanitation.

Lack of clean water and basic sanitation results in 2 million deaths per year, 90 percent of them young children, from diarrheal diseases. It is also a factor in other diseases, like malaria, schistosomiasis and Guinea worm. Over 2 billion people are infected by schistosomiasis, with 300 million suffering serious illness. Well-designed water and sanitation investments reduce these infections by three-quarters. Pollutants like heavy metals and pesticides are also a problem: Over 50 million people in Asia drink water with high levels of arsenic.

At the same time, 800 million people living in rural areas lack access to adequate water for agriculture. Since green revolution crop varieties require more water, farmers who cannot afford wells and pumps cannot take advantage of these improved crops.

The proposals here included investment in community-based water and sanitation systems (standpipes and latrines), investment in small-scale water technologies for agriculture and investment in research to improve water productivity in food production.

The magnitude of the problem at first seems overwhelming, but the situation is less dire than the numbers suggest. About half of those without clean water and basic sanitation live in China and India, countries that have enjoyed rapid economic growth over the last two decades. Both of these countries are well poised to make the necessary investments on their own, and the same is true in a number of other countries. In South Asia, there has also been a spontaneous rise in the use of groundwater or pump irrigation systems powered by small engines.

Sub-Saharan Africa, with around 360 million unserved people, is another story. Here there is little reason to think that the problem will be solved without outside assistance. Intervention should be focused on this region and a few others, where growth is stalled and internal investment will probably not be forthcoming anytime soon.

Carrying dirty water from streams and rivers requires substantial time and energy, so even the very poor are willing to pay for easy access to clean water for drinking, cooking and so on. The benefits from basic sanitation, on the other hand, are largely public, and the private willingness to pay is correspondingly less. Many of the health benefits derive from better sanitation, however. A successful strategy is to fund linked projects that make initial investments in both types of infrastructure. Subsequently, user fees for water can be employed to finance maintenance for both systems. The B/C ratio was reported to be 5, but that figure did not include any provision for lives saved through reduction of diarrheal and other diseases.

The proposal for water for agriculture involved investments in small-scale projects: small, low-cost electric and diesel pumps, treadle pumps, bucket and drip lines, rainwater harvesting, micro-sprinkler systems, drip irrigation lines and low- or zero-till agricultural techniques. Costs for these technologies are already low—at most a few hundred dollars and much less for some—and are falling further. In some areas, spontaneous markets for these technologies are already growing. In other areas, social marketing, micro-credit lending and programs for training and technical support can be useful in spurring adoption. The benefits from these investments take the form of higher yields from crops currently under cultivation and the ability to switch to high-yield varieties or to high-value cash crops. The B/C ratio was estimated to be 7.

The third project was funding of further research to develop crop varieties that are less water-dependent, an idea that has substantial overlap with one of the hunger and nutrition projects. The B/C ratio was estimated to be in the range of 15-20.

Subsidies and trade barriers Liberalizing world trade is the closest thing to a free lunch that one can imagine. Reducing subsidies and lowering trade barriers would cost little in terms of direct outlays—indeed, reducing subsidies would save money—and doing so would raise income levels and growth rates around the globe.

The potential gains from liberalizing world trade are enormous. Using large-scale models, various research teams have calculated gains that range from $254 billion to $2,080 billion per year (in 1995 U.S. dollars). As shown in Table 3 (below), low-income countries would reap about 43 percent of the total gains.

Table 3 Regional gains from trade |

|||

|

Liberalizing region |

||

|

Low-income |

High-income |

Total |

Low-income |

25.6 |

16.9 |

42.5 |

High-income |

19.5 |

38.0 |

57.5 |

Total |

45.1 |

54.9 |

100.0 |

Benefiting region |

|

|

|

Source: Lomborg (2004, Table 10.2) |

|||

Many of the gains from lowering trade barriers would accrue from unilateral action. Own-country reforms lower prices for consumers and shift the allocation of resources toward more efficient producers. The effect is especially strong for small economies, which have the most to gain from the ability to purchase in the global marketplace.

Given the magnitude of these potential gains, why hasn't progress toward free world trade been faster? Only a small number of low-income countries depend on tariffs as an important source of government revenue, but trade taxes are widespread. The purpose of these taxes is typically to protect producers, both workers and owners of capital, in certain industries or sectors. Since protection arises for political reasons, any attempt at reform must confront the fact that protective tariffs arise as the equilibrium of a political process. Nevertheless, better information about the potential benefits can help to change the outcome of this process, as can programs that offer temporary assistance to those who will lose when tariff protection ends.

At present, the World Trade Organization's efforts to expand the scope of nonpreferential trade agreements offer the most promising steps toward general liberalization of world trade. Other avenues are reciprocal, preferential agreements, like the North American Free Trade Agreement and the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas, and nonreciprocal preferential agreements like the one proposed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to allow free market access to a specific list of least-developed countries. But preferential agreements generate much smaller gains, and they lead to trade diversion as well as trade creation, imposing losses on the excluded economies that can completely offset the gains to the insiders.

Openness also seems to stimulate growth. The data are not entirely clear, since lower trade barriers and faster growth may both simply result from better overall government policy. Nevertheless, both economic reasoning and evidence suggest that a direct link is plausible. For example, in many countries, the ability to purchase imported capital equipment at reasonable prices is an important factor in investment decisions. Chile and China, which liberalized in the 1980s, and India, which followed suit a little later, all enjoyed rapid growth afterward.

If lowering trade raises growth rates by even a modest amount, the gains will be enormous. Aggregating over time, and allowing a modest impact of trade on growth rates, the present discounted value of the total net gain from a complete liberalization is a staggering $44 trillion (in 2002 U.S. dollars). A more modest reform has about half those benefits, with a B/C ratio of 24.

The Rankings

In total, about 30 serious proposals were put forward. Given the overall goal of the project, the big question was then: Was there consensus? That is, did the panel members agree—more or less—on which projects should be given the highest priority? Note that consensus in this sense does not require agreement about the numerical values for the B/C ratios attached to various projects. It only requires similar rankings for those ratios, and hence for the projects, and only at the top of the list.

Among the 30 serious proposals put forward in the Challenge papers, about half came with B/C ratios calculated by the authors. Table 4 (below) contains a summary of those ratios. (The list omits "straw men" and a few proposals that were left unranked for other reasons.)

The quantity, quality and detail of the cost and benefit figures that went into these B/C ratios varied greatly across areas and projects. The papers on climate change and international trade drew on a wealth of earlier research explicitly aimed at estimating costs (for climate change) and benefits (for both). The proposals on communicable diseases, water and sanitation, and nutrition used evidence from earlier projects, both to identify successful project designs and to estimate costs and benefits.

The papers on civil conflict, financial crises, governance and migration, on the other hand, while providing good discussions of the problems and some interesting and innovative ideas for solutions, had little to draw upon in terms of historical evidence or previous research. The paper on education took a pessimistic view of what could be done with extra resources, and its only serious proposal, a call for systemic reform, had no figures attached.

None of the ratios reported in Table 4 can be viewed as accurate, and for some, "rough estimate" is a generous description. The discussions brought out information about important omissions and biases, and about the reliability of the data underlying the cost and benefit figures.

In some cases the direction of a bias was clear, even if the magnitude was not. Saving lives was always undervalued relative to the method described earlier, so the B/C ratios in Table 4 are understated for projects where that is an important benefit. The climate change proposal used only low discount rates, causing the B/C ratios to be overstated. The benefits of trade liberalization have been intensively studied, but the costs have not been. The cost figure used to calculate the ratio in Table 4 was deliberately chosen by the author "so as not to exaggerate the net gains from trade reform." Thus, the true B/C ratio is likely much higher. The proposal for reducing financial instability is novel, and there is no direct evidence on whether it would be effective. The proposed reform might have enormous gains at negligible cost, as claimed by the author, or it might achieve nothing. The true B/C ratio could be zero.

So the figures in Table 4 should be taken with many grains of salt, and the panel members took them that way. Indeed, if the figures were accurate, the panel of economists and the week of discussions would have been superfluous: Anyone could simply set aside the projects without B/C ratios and rank the rest.

In the end, each panel member adjusted the figures in Table 4, explicitly or implicitly, for factors he or she felt had been misvalued or omitted, and ranked as many proposals as he or she felt able to assess. These individual rankings were then aggregated. Most panel members ranked approximately the same group of proposals, producing in the end a group ranking of 17 projects.

Was there consensus? Table 5 displays the individual and group rankings. Consensus, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, but to me the rankings display a great deal of agreement. At the top of the group ranking are four projects: to control HIV/AIDS ($27 billion), to provide micronutrients ($12 billion), to liberalize world trade and to control malaria ($13 billion). Most of the panel members ranked the first two of these very high, and there was only moderate disagreement about the third and fourth. The budget of $50 billion, the figure used to frame the exercise, would finance these four projects.

There was also a great deal of agreement about the other rankings. The next group, five projects labeled "good," included the proposal to invest in developing new agricultural technologies, the three water and sanitation proposals and the proposal to lower the barriers to starting a new business. Four more proposals were ranked by the group as "fair," those lowering barriers to migration for skilled workers, improving infant and child health (two projects) and improving basic health services.

The three proposals on climate change appeared at the bottom of every list and were unanimously judged to have costs that exceeded their benefits. The proposal to promote migration by unskilled guest workers also fared badly in terms of the group rankings, but it is one proposal about which there was considerable difference of opinion. Three panel members put it in the good to fair range, and two left it unranked.

Most of the proposals that had no figures attached were left unranked. Many of these were general ideas (reform revenue collection) rather than specific projects (distribute bed nets in SSA) and, hence, quite difficult to compare. The proposal to deal with financial instability was also left unranked. It was a novel idea with no track record, and most panel members felt unable to assess its prospects for success.

What were the sources of the consensus? At the top of the list, much of the agreement resulted from a common view on valuing human life, which gave high priority to the HIV/AIDS, malaria and micronutrient proposals. Liberalizing world trade offers large benefits at a very modest direct cost, but several panel members ranked it lower because they felt there was little point in promoting such an old idea.

At the bottom of the list, there was unanimous agreement about the three climate change proposals. All were variations on a common theme, incurring enormous abatement costs right now in exchange for climate benefits in one or two centuries. It is worth emphasizing that the panel did not think that global climate change is an unimportant issue. During the discussion, it was clear that other types of projects, such as funding research on the underlying science of how atmospheric pollutants affect climate or developing better methods for reducing carbon emissions, would have received a more sympathetic hearing.

Many of the numbers were rough and ready, and they were not always presented in a way that allowed easy comparison across proposals. It is clear, however, that the numbers could be improved with more time and effort, and could be made consistent with each other if more precise guidelines were used. Improving the figures would surely alter the rankings to some extent, but the differences among some projects were so great that reversals seem unlikely.

Overall, several lessons can be learned from the exercise. First, the difficulty of making comparisons highlighted the potential value of systematic experimentation. Although the proposals for HIV/AIDS, malaria and micronutrients referred to results of previous projects, the evidence was limited. Experimental programs that are designed, like drug trials, to deliver better information about precisely what is successful and what is not would be valuable for two reasons. Such programs would allow a clearer assessment of where funds should be directed, and they would improve the design and enhance the effectiveness of funded projects.

In addition, two important issues that benefit/ cost analysis neglects became apparent. One is the cost of delay. Controlling HIV/AIDS got very high priority partly because of the urgency of the problem. Prevention is much less costly than treatment, and prevention becomes more expensive as the infection rate rises. But "urgency" is not something that benefit/cost analysis takes into account.

Another is the presence of political or social costs. Some of the proposals involved little or nothing by way of out-of-pocket expenditures, but nevertheless had costs in other dimensions. Liberalizing world trade, lowering barriers to migration and lowering the costs of starting a new business are reforms that require political will rather than financial investments.

Finally, one important global problem, neglected thus far, deserves some discussion. Nowhere among the Copenhagen proposals were any aimed explicitly at promoting economic growth or reducing extreme poverty. Why? Not because poverty is unimportant: Lifting people out of poverty would solve a host of other problems. And not because poverty is inevitable: The best estimates indicate that the poverty rate has fallen substantially over the last two decades.

The poverty rate is not falling because of programs sponsored by the U.N., the World Bank or other donor organizations, however. China and India, two countries with large populations and low per capita incomes 20 years ago, have enjoyed rapid economic growth. Growth in those two countries alone has raised an enormous number of people above the extreme poverty threshold, and other countries could be added to the list. But incomes are growing in China and India because of internal reforms, policies or policy changes that they adopted themselves. The same is true in other countries now and for earlier growth miracles, countries like Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, Taiwan in the 1960s and 1970s, and Korea in the 1970s and 1980s. On the other hand, it is hard to think of even one case where outside intervention has transformed a stagnant economy into a growing one.

Easterly (2001, 2006) discusses this issue in more detail, cataloging the many failed attempts to promote economic growth in poor countries. He estimates that the West, through the World Bank and other organizations, has spent $2.3 trillion over the years on foreign aid. A number of different approaches have been tried—subsidizing investment, promoting education, encouraging institutional change and policy reform, and financing debt relief—and none has raised growth rates. In Africa, where much of the money has been spent, growth rates have in fact fallen.

Until we better understand how aid can promote growth, it is prudent to concentrate resources in areas with more successful track records. Projects aimed at improving health and prolonging life in the poorer regions of the world have achieved a great deal in the past, and they seem to offer some of the best prospects for the near future as well.

References

Easterly, William. 2001. The Elusive Quest for Growth. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Easterly, William. 2006. The White Man's Burden. New York: Penguin Press.

Lomborg, Bjørn. 2004. Global Crises, Global Solutions. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Miguel, Edward, and Michael Kremer. 2004. Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities. Econometrica 72(1): 159-217.

Psacharopoulos, George, and Harry Anthony Patrinos. 2004. Returns to Investment in Education: A Further Update. Education Economics 12(2): 111-34.

Schultz, T. Paul. 2004. School Subsidies for the Poor: Evaluating the Mexican Progresa Poverty Program. Journal of Development Economics 74(1): 199-250.

About the AuthorNancy L. Stokey, who has served as a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis in recent years, has written a number of important papers on issues relating to economic development, growth, trade, social mobility and related topics. Stokey has served on the executive committee and as vice president of the American Economic Association, on the council of the Econometric Society and in editorial positions with Econometrica, Games and Economic Behavior, The Journal of Economic Growth and The Journal of Economic Theory. For more about Stokey, including her thoughts on economic growth in lesser-developed countries, read her interview with The Region magazine. |

* The Copenhagen Consensus project was organized in 2002-03 by Bjørn Lomborg, the author of the controversial book, The Skeptical Environmentalist. The project was funded by the Danish Ministry of the Environment, the Tuborg Foundation, the Carlsberg Bequest to the Memory of Brewer I.C. Jacobsen and The Economist. Previous articles in The Region: Web Site: |