As suggested by the well-worn tale of the two-handed economist (on the one hand..., on the other hand...), establishing economic certainty is a difficult task. Economics works slowly and tentatively. Researchers develop theories, test them and offer their findings to the broader community of economists which, in turn, may confirm, refute or ignore the new ideas.

Research economists at the Minneapolis Fed engage in precisely this multistaged, iterative process. They search for economic truths by constructing hypotheses, designing models, checking against data, writing up working papers, presenting at seminars, absorbing feedback from colleagues and then refining ideas into staff reports that are circulated more widely.

Eventually the staff reports may be published in professional journals, after further painstaking review. (The language of this review process is evocative: When an author sends a paper to a journal, hoping for "acceptance," the process is called "submission." Anonymous economists who critique the paper and demand time-consuming revisions are "referees.") Papers that survive this gauntlet and appear in professional journals are then subjected to still further rounds of scrutiny by the economics community at large.

Old problems; new perspectives

Three recent staff reports developed by Minneapolis Fed economists present fresh ideas on old topics. These papers have yet to face the trials of broad review, but each displays original thinking that—should it prove valid—will contribute significantly to the field. Indeed, even the rejection of a hypothesis helps to establish economic truth by ruling out false explanation.

Minneapolis Fed research economists

Cristina Arellano, Alessandra Fogli and Henry Siu

In January 2007, Fed economists Cristina Arellano and Jonathan Heathcote released a staff report that presents a novel theory about the potential benefit of one nation adopting the currency of another. Then in February, visiting scholar Alessandra Fogli issued a paper that provides an ingenious explanation of female workforce trends. And in March, Fed visiting scholar Henry Siu released a staff report with a cogent new hypothesis regarding diminished economic instability in industrialized nations.

Here we present the broad outlines of their work (for details, follow links to the papers themselves) as an indication of the range and depth of innovative thinking emerging from the Fed's research economists.

Full Faith and Credit

Gaining trust is a complicated undertaking, particularly when experience has proven that trust unwarranted. In the sphere of international lending to emerging economies, trust is scarce precisely because loans have, indeed, often gone unpaid. Argentina's dramatic default in 2001, for example, served as a warning to lending agencies-especially the International Monetary Fund-that the best laid plans and purest intentions are no guarantee that those who borrow will repay.

But access to international capital can be critical to a nation's economic progress. Foreign loans may finance investment in physical infrastructure, social programs or any number of development projects. So what steps can be taken by an emerging economy (or any economy for that matter) to establish or enhance trust in its ability and willingness to repay loans?

Fed economists Cristina Arellano and Jonathan Heathcote explore dollarization as a mechanism that nations can use to increase their international credibility. They use the term "dollarization" to refer to a country's adoption of a foreign currency with recognized international strength-the euro and yen fit the definition as well as the dollar. And the economists demonstrate that while dollarizing entails sacrifices, it may hold real potential as a means of establishing financial credibility, increasing access to credit and raising economic welfare.

"Dollarization may be attractive precisely because eliminating the monetary instrument can strengthen incentives to repay debts, and thereby increase access to international credit," write Arellano and Heathcote in "Dollarization and Financial Integration" (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Staff Report 385). "This is a new way to think about how relinquishing monetary independence may strengthen credibility."

A debatable proposition

Economists and policymakers have long debated the benefits and costs of one nation adopting another's currency. The debate intensified in the 1990s as currency and financial crises wracked emerging markets in Latin America, Asia and elsewhere. "After these crises, there were a lot of questions of whether the type of exchange rate regime might influence the way that crises get resolved," recalls Arellano, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota and a visiting scholar at the Minneapolis Fed.

In addition, many emerging markets owed debt in foreign currency, and adverse exchange rate trends impeded debt repayment. "Aligning assets and liabilities through some fixed exchange rate like dollarization might address that problem," Arellano notes. The debate is not confined to emerging markets, however. In Europe, nations considering membership in the Economic and Monetary Union have had to weigh the benefits and costs of abandoning monetary policy through membership in a currency union.

A clear cost of dollarization is the sacrifice a nation makes in relinquishing control over the production and distribution of its own currency. "Retaining the ability to print one's own currency," write the economists, "gives governments a flexible way to raise revenue."

The revenue source is seigniorage, the resources a government obtains by printing currency and spending it. In simple terms, seigniorage equals the change in a nation's money supply divided by the price level. Governments in many nations, especially emerging markets, have often relied heavily on seigniorage since taxes are prone to evasion and raising them is fraught with political consequence. A 1998 study of 90 countries found that seigniorage on average amounted to 10.5 percent of government spending between 1971 and 1990.

The benefits of sacrifice

But the adoption of an internationally recognized currency also has significant advantages. Dollarizing can diminish inflation by eliminating a government's ability to achieve short-term economic spurts by increasing the money supply. Policymakers may be tempted to use monetary policy to smooth business cycles by creating a bit of surprise inflation during recessions, a problem brought to light by economists Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott. By dollarizing, a nation's policymakers surrender their control over monetary policy and thus eliminate this inflationary tendency.

Another benefit: Dollarization can increase trade by removing transaction costs involved in exchanging one currency for another and also by reducing currency risk—the potential for terms of trade between currencies to shift against one's own.

But Arellano and Heathcote focus on a different advantage to dollarizing. "The model we develop in this paper," they write, "is deliberately designed to abstract from these potential benefits in order to clarify the trade-off in the dollarization decision between the loss of seigniorage as a flexible fiscal instrument on the one hand, and the potential increase in international financial integration on the other."

Trust me

The notion advanced by Arellano and Heathcote is that a nation that sacrifices its ability to obtain seigniorage increases its credibility with international lenders. Lenders will realize that a nation that can't print its own money will become crucially dependent on borrowing from abroad. Since access to future loans is contingent on repaying current debts (a condition the economists build into their model), lenders know that nations lacking seigniorage are likely to behave themselves in international debt markets.

"The logic is that because dollarizing rules out the use of monetary policy to respond to shocks, it may increase the value ... of maintaining access to the debt instrument," argue Arellano and Heathcote. "Thus if default is punished by exclusion from debt markets, dollarization effectively reduces [a nation's] incentive to default, and thereby increases the amount of borrowing that can be supported."

A model

To test the hypothesis, the economists construct a model with two key policy instruments: the growth rate of the money supply and the level of international debt. They also build in two sources of risk: fluctuation in economic output and fluctuation in consumer preferences for private goods or public goods. (As it turns out, whether these two risks are positively or negatively correlated is a key predictor of whether dollarization is likely to benefit a nation.)

Then they run the model with data from Mexico and El Salvador. First Arellano and Heathcote look at both countries under a floating exchange rate—meaning that policymakers retain control over monetary policy and the national currency floats in value relative to other currencies—and generate results for foreign borrowing, savings and debt. The economists then repeat the exercise with the assumption that both countries have dollarized. The contrast is striking.

In El Salvador, dollarization increases the government's ability to borrow, predicts the model, raising the borrowing constraint from 7 percent of gross domestic product in a floating economy to 8.3 percent of GDP when dollarized, and debt can be used more actively (see table). "Dollarization also reduces the frequency of financial crises," write Arellano and Heathcote, meaning that episodes of the government not being able to borrow as much as it needs become less common, dropping from 10 percent of the time to 6 percent.

But for Mexico the model predicts that a shift to dollarization would lead to poorer outcomes. The country's foreign borrowing limit would shrink from about 3.5 percent of GDP to less than 1 percent, debt could not be used as aggressively to finance expenditure and borrowing constraints would crop up more frequently. "Dollarization reduces international financial integration for Mexico," write the economists. "Because dollarization means both the loss of an instrument and the loss of credibility in international financial markets, it comes as no surprise that [economic] welfare is higher under a float."

Source of disparity

A bit of mental gymnastics is essential for grasping exactly why dollarization improves the situation for one country but not the other. Essentially, it boils down to the kinds of economic variations each country experiences, the correlations among them and the ways that policy instruments can be used to address those variations.

"If you have output and government consumption co-moving negatively, like in El Salvador, and you're dollarized so you can't adjust the monetary growth rate, then debt is really useful," explains Heathcote, currently at the Federal Reserve Board's International Finance Division, on leave from Georgetown University. "The times when you want to spend more are the times when the government is collecting less regular tax revenue. So in those periods, you'd really like to borrow a lot and then pay back in some subsequent period. Consequently, there's a big cost to being shut out [of international lending markets]."

In an e-mail, the economists offer a metaphor. "Think of debt and inflation as two ingredients the government is using to make a cake. For Mexico, debt and inflation are like flour and butter: Without the butter, you couldn't really care less whether you get the flour, because you aren't going to do much baking. But for El Salvador, debt and inflation are like margarine and butter: If you don't have the butter, you really want the margarine."

An intricate dance

This complex interplay of policy instruments and economic fluctuations leads to the disparate results: Dollarization is good for an economy like El Salvador's, but a bad choice for Mexico.

"In El Salvador, dollarization looks much better in terms of greater access to borrowing and lower probabilities of being in crisis," Arellano says in summary. "But for Mexico, we find that after dollarization it's not going to be able to borrow more. ... It would lower their welfare because it no longer has the monetary instrument and isn't increasing its credibility in financial markets."

The "simple" model thus paints a complex picture, admits Heathcote. "All these details are hard to get across, but they all matter. It matters what kinds of shocks you're hit by, and it matters how those shocks are correlated. There's no one-size-fits-all prescription." And indeed, this flexibility is one of the model's real strengths: its ability to make differential predictions rather than draw blanket conclusions. The world economy is too complex for single-bullet solutions.

|

To see what the data say about dollarization and international lending, and for an economist's perspective on dollarization in Ecuador, see "Reality Check" and "Everything Was a Dollar." |

Women at Work

In the United States, whether or not mothers with young children should work outside the home has long been a divisive issue. Mothers themselves are often torn between a wish to sustain their professional careers and a desire to nurture their children by staying at home with them. But there is no question that women joined the labor force in increasing numbers during the 20th century and that women with young children were a major factor in that rise.

New York University economist Alessandra Fogli, a Minneapolis Fed visiting scholar, and Laura Veldkamp, also at NYU, examine this trend and seek to explain it with a model of learning and belief. The labor force participation of mothers with young children, suggest the economists, is strongly influenced by mothers' beliefs about the effects of that participation on their children, which are shaped by observing the children of their peers in the labor force. This interaction of action and belief—each informing the other—underlies an economic model that helps explain much about the trends in work patterns and attitudes of American women throughout the 20th century.

"We argue that beliefs are formed and evolve over time as women learn about the relative importance of nature and nurture in determining children's outcomes," write Fogli and Veldkamp, in "Nature or Nurture? Learning and Female Labor Force Dynamics" (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Staff Report 386). "A crucial factor in a woman's choice to work is the effect of her employment on her children."

Fogli and Veldkamp contend that after women learn through observation about the impact on children of mothers taking jobs, they modify prior beliefs and use new beliefs to guide their decisions about whether to take jobs. As more women join the labor force, more information about child outcomes becomes available, exerting a stronger influence on other mothers, and accelerating participation trends. Eventually, "as beliefs converge to the truth, learning slows down and participation flattens out."

Parallel trends

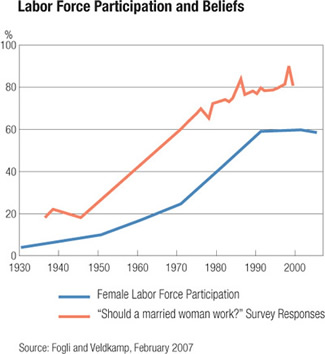

In their paper, the economists first document two distinct phenomena: the evolution of public attitudes about women in the workplace and the trend in labor force participation by women.

Public attitudes are gleaned from responses to several survey questions asked of the U.S. public between 1936 and 2004 about women's labor force participation—questions such as "Do you agree or disagree with the statement 'women should take care of running their homes and leave running the country up to men.'?" The survey responses show very little approval of working women in the early years, with a significant increase over time, and then a slowing trend during the past 15 years or so.

They then review data on female labor force participation during the same period. Between 1930 and 1950, female LFP rates rose very slowly. In the 1950s and 1960s, rates climbed more quickly, and in 1970 they accelerated dramatically until about 1990, when participation rates leveled off. "What is striking," they note, "is that the labor force participation tracks the survey responses so closely and that both display an S shape." (See graph.) (They emphasize that the greatest part of the increase in female labor force participation came from married women with children. And married women with children under 5 years of age showed an especially dramatic LFP increase, from under 4 percent in 1930 to 59 percent in 2004.)

Model building

Are these parallel S tracks a coincidence? To answer that question, the economists develop a mathematical model whose key element is that both nurture and nature play a role in determining an individual's earning potential. Nature is inherited directly from parents, according to their model, but nurture depends on a mother's decision about joining the labor force, based on an uncertain knowledge of how that decision will impact her child's future ability. Mothers resolve their uncertainty, to a degree, by seeing the outcomes of other children whose mothers work. That feedback mechanism shapes the curve.

The economists find that their model generates an S-shaped pattern of labor force participation. "Learning is slow at first because few women work, making data about labor force participation scarce," they explain. "As women learn, participation increases and speeds up learning." But a competing influence slows the acceleration. "As beliefs become more informed, new information affects them less." At that point, participation levels off.

The theoretical run-through is confirmed with an empirical simulation. Using a calibrated model, they generate results that mimic actual data quite closely. The S-shaped curve of their model's simulation of female labor force participation matches the data well, and the model-generated curve for positive beliefs about female labor force participation closely resembles real attitude trends. "The S-shaped increase is consistent with the survey evidence," they write.

Thus, the graphs illustrating the theory match reality well. "When labor force participation is low, information about the cost of maternal employment on children is scarce, and beliefs change slowly," they explain. That means that participation also rises slowly. But over time, "as that rate rises, more information is generated by working women whose children's outcomes are observed. Beliefs and participation change at a faster rate. Once information becomes sufficiently abundant, beliefs and labor force participation converge, in unison, to their new steady-state values."

Other explanations

Although their learning model appears to have strong explanatory power, the economists don't dismiss other potential explanations. The shrinking wage gap between men and women, for example, has often been suggested as a powerful force bringing women into the workforce. (See "Wives at Work," The Region, December 2003)

But Fogli and Veldkamp note that "wage-based explanations have a hard time" reconciling recent trends, "particularly in the last 20 years while wages were rising and labor force participation stagnating." Their theory, by contrast, predicts this stagnation: "Labor elasticity fell because uncertainty about the effects of labor market participation fell." Still, they admit, wage increases are "an important component" of the female labor trend. "Our theory can modify the predictions of wage-based theories to allow them to match more nuanced theories of the data."

Fogli and Veldkamp review other potential explanations, including improved technologies that "liberated" women from household work and preference changes over time. These explanations, like those based on wage trends, don't explain the fall in labor supply elasticity—a key strength of their theory. But the economists don't suggest that they should therefore be dismissed. Several "mechanisms could be operating simultaneously," they write.

More broadly, the economists point out that their theory provides insight into how social change occurs—through learning from endogenous information. When people experiment with alternatives to societal norms, they generate information that others observe. "As more people deviate from the culture norm, learning speeds up, social change quickens and a social revolution takes hold."Demographics and Economic Volatility

In 2004, then Fed Governor Ben Bernanke addressed the "Great Moderation"—the remarkable decline in economic volatility observed in the United States and other advanced economies over the past two or three decades. He reviewed evidence for three explanations: structural change, good luck and improved policy, and then he focused on the last: the role that better monetary policy has played, particularly in the United States. (Of course, his current job gives him a somewhat unique opportunity to test his hypothesis.)

In a recent paper, Fed visiting scholar Henry Siu of the University of British Columbia and Nir Jaimovich of Stanford University develop a new theory to help explain the Great Moderation in not only the United States but other industrialized economies. "Specifically," write Jaimovich and Siu, "we find that changes in the age composition of the workforce account for a significant fraction of the variation in business cycle volatility."

In "The Young, the Old and the Restless: Demographics and Business Cycle Volatility" (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Staff Report 387), the economists begin by documenting age variations in labor market volatility. The task is easiest in the United States and Japan, which compile data on average hours worked by different demographic groups. Both nations, they find, display profound differences across age groups.

In the United States, the young exhibit far greater fluctuation in hours worked per capita than the middle-aged; those at or close to retirement fall somewhere between. By one statistical measure, employment fluctuation for workers 15 to 19 years old is over five times that for those 40 to 49 years old. So while teenagers account for just 3 percent of total employment, they account for 11 percent of employment volatility. And the volatility of workers 65 years and older is about twice that of those 40 to 49 years old—not as volatile as teens but still quite high.

The relationship is similar in Japan. "As in the U.S.," they write, "there is a distinct U-shaped pattern to ... volatility of hours worked as a function of age."

For the other G7 members—Canada, France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom—the economists look at employment rates since age-specific data on hours worked aren't available. While the nations vary, each strongly displays the same relationship: Younger and older workers have far more labor market volatility than the middle-aged. Averaged across the seven countries, employment volatility "for 15-19 year olds is nearly six times greater than that of 40-49 year olds," conclude Jaimovich and Siu. "Similarly, the average employment volatility of 60-64 year olds is about three times greater than that of 40-49 year olds."

This pattern is remarkable, they note, given the significant dissimilarities among these nations. "That these economies differ greatly in terms of industry composition and the degree of labor market regulation makes this finding all the more striking [which suggests] that the age composition of the labor force is potentially a key determinant of the responsiveness of an economy to business cycle shocks."

Demographic differences

Having established a similarity among G7 countries—in all seven, the young and old have higher employment fluctuations than the middle-aged—the economists take the next step: examining cross-country differences in the extent and timing of demographic change. These differences are crucial to their strategy for discerning the relationship between demographics and business cycles.

In the United States and Canada, post-World War II baby booms led to a large cohort of "20-something" workers in the 1970s and a subsequent boom in "prime-aged" workers beginning in 1990 or so. But France, Italy and Germany had far smaller baby booms, and the labor force has gradually aged. The United Kingdom fell between those extremes, while Japan experienced a strong decline in fertility after World War II, resulting in an increasing share of workers over 60 years, especially since 1980.

The economists exploit these differences in demographic trends to determine the impact of labor force age composition on economic volatility. After all, a simple correlation in a specific country between trends in economic volatility and shares of the labor force made up by young workers could be mere coincidence, they note. The increase in U.S. volatility from 1960 to 1978, for example, might be due to unstable oil prices, not unstable teenagers. But finding the demography/volatility correlation in several countries—which face the same oil prices, but very different demographic patterns—"strongly suggests that the correlation is not spurious."

Their graphs provide a striking picture. (See charts.) In six of the seven G7 countries, the economists observe, "business cycle volatility and the volatile labor force share clearly co-vary." The relationship is weaker in France, they admit, "but relative to the other countries, there is little change in volatility to explain."

Measuring magnitude

To measure the degree to which age distribution impacts volatility, the economists use regression analysis, a statistical technique that gauges how much different factors influence a specific outcome. (Regression equations might be used, for instance, to estimate the impact of higher teacher salaries on student test scores, holding other factors constant.) In this case, the economists input data from the seven countries over a span of several decades and, in a "first cut" estimate, find that a 10 percent increase in the volatile share of the labor force (15-19 year olds plus 60-64 year olds) would increase economic volatility by 0.402.*

After experimenting with various age-group definitions and statistical refinements, and expanding the analysis to the entire age distribution rather than simply the "volatile" share, they estimate a slightly stronger impact: A 10 percent labor force shift into the most stable age group (40-49 years) will decrease volatility by 0.406.

So, if this estimate were applied to the United States and the Great Moderation that Bernanke discussed, how much of this moderation might demographic change explain? Again, the economists point out, conventional explanations for the moderation include improved monetary policy, regulatory changes and financial market innovation, and good luck in the form of reduced volatility of business cycle shocks. All told, these and other forces reduced U.S. volatility from a peak of 2.379 in 1978 to a much lower figure of 0.955 by 1999, a 1.424 point drop.

During that same time span, Jaimovich and Siu point out, the volatile share of the labor force dropped from 38.5 percent to 27.1 percent, an 11.4 point reduction. According to their regression estimates, "such a shift in workforce composition ... predicts a volatility reduction [of] 0.463." Thus, they estimate, demographic change accounts for roughly 32 percent (= 0.463/1.424) of total macroeconomic moderation between 1978 and 1999.

Using a different statistical method for measuring the impact of age shifts, the economists generate a more modest estimate, about 21 percent. Still, it's in the same ballpark. "That the results ... are similar in magnitude ... we take as evidence for an important role for demographics in explaining the Great Moderation."

Business cycle models

The final step in this ambitious paper is to build a mathematical model that can analyze the relationship between differences in labor force age volatility and trends in general economic volatility. The economists take a standard "real business cycle" model and modify it accordingly. The key elements of their model are a workforce dichotomy between young/inexperienced workers and old/experienced workers, and a production technology that exhibits complementarity between capital and older/experienced workers. Thus, any business cycle shock generating a change in employment will result in bigger changes in the quantity of young labor hired and fired.

The economists refine the model and run it, generating simulated figures for labor and output for the United States between 1968 and 2004. The simulations do a good job of matching real data over that time span on volatility of young and old worker hours relative to output, and they closely replicate the Great Moderation driven solely by changes in volatility of shocks and share of young and old workers.

Model in hand, Jaimovich and Siu use it to measure the magnitude of impact. With a few run-throughs, they estimate that demographic change accounts for between 10 percent and 15 percent of the moderation in output volatility and between 15 percent and 25 percent of moderation in aggregate hours volatility. "In summary," they conclude, "this simple variant of the RBC model with capital-experience complementarity attributes a similar role to demographic change in the moderation of macroeconomic volatility" to that predicted by their earlier statistical estimates.

In other words, their model, their regression analysis and their other estimation techniques all arrive at the same robust conclusion: "Variation in the age composition of aggregate hours accounts for a significant fraction of the moderation in U.S. business cycle volatility."

* The units for volatility discussed here and in the following paragraphs can be described as the standard deviation of fluctuations in real GDP from its trend.