Fifty years ago the poster child for universal service was an elderly widow living in a prairie hamlet, unable to call the doctor because she didn't have a telephone. She was stuck on the wrong side of the rotary-dial divide. Today, in the minds of some lawmakers, the country widow has morphed into a home-based entrepreneur forced to use a slow dial-up Internet connection to surf the Web and send large files to her clients in the city. In an era when ease of communication is measured in bandwidth, dial-up is Nowheresville.

Rural households lag behind those in urban and suburban areas in their use of high-speed or broadband Internet service, creating concern about a "digital divide" and a perception that the nation is not a leader in broadband use. (Last year the International Telecommunication Union ranked the United States 15th in broadband subscribers per capita, behind Canada, Taiwan and several European countries.) This has prompted proposals to extend universal service to high-speed Internet access—cable modem, digital subscriber line (DSL), fixed wireless and other technologies that transmit information many times faster than a dial-up link.

In addition to basic telephone service, the universal service fund (USF) currently subsidizes broadband Internet access for schools, libraries and rural health care facilities, but not rural households and small businesses.

A bill introduced in Congress by Sen. Ted Stevens of Alaska would change that, giving telecom firms up to $500 million annually for the deployment of broadband equipment and infrastructure in rural and other "unserved" areas of the country. Stevens' bill follows on the heels of several failed attempts in the previous session of Congress to spur broadband deployment in sparsely populated areas, through either the USF or other federal programs. One 2006 measure would have required telecom firms that receive universal service funding to offer broadband with a download speed of at least 1 megabit per second (Mbps) within five years. Another bill sponsored by Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton would have established a special broadband office within the Department of Agriculture to administer existing and newly created grant and loan programs intended to foster broadband deployment in rural areas.

Increasingly in public policy circles, access to broadband is viewed as crucial to economic development and social progress. A high-speed line makes small businesses more productive, facilitates home-based health care and distance learning, and opens a pathway into homes for alternative voice technologies such as cable and Internet telephony. A number of government and academic studies in recent years have shown that the presence of broadband enhances economic growth and performance in local communities and the country as a whole.

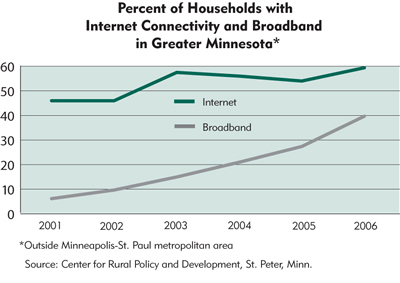

But all the attention given to the urban-rural broadband gap prompts a question: Are universal service and other types of subsidies really needed to close that gap, given the current state of broadband in rural areas? In a spring 2006 survey of home broadband use by the Pew Internet & American Life Project, only one-quarter of rural U.S. households subscribed to high-speed Internet access. A more recent study of Internet use in Minnesota found that less than 40 percent of rural households had broadband, versus 57 percent in the Twin Cities metro area.

To some policymakers and telecom pundits, the numbers mean that private markets have failed to make broadband sufficiently available in rural areas, so government must step in to encourage deployment, just as it did with universal phone service. "We must ensure that no group or region in America is denied access to high-speed connections," wrote former Federal Communications Commission Chairman William Kennard last fall in a newspaper editorial calling for universal service reforms to support expanded broadband access.

But it may be too early to worry about slow broadband adoption in rural areas, including nonmetro areas of the Ninth District. Broadband has established a strong presence in rural areas, and consumers have adopted it—at market prices, no less—at a much faster rate than other technological innovations, including the ubiquitous and oft-subsidized telephone. This suggests that in time, private investment and constantly improving technology will bring affordable high-speed connections to even the remotest areas.

Fewer blank spots

Broadband availability in rural areas of the district has increased by leaps and bounds over the past few years. No longer is it a given that urbanites get to cruise the information superhighway while rural residents trundle along the shoulder, dependent on dial-up. Broadband coverage still isn't as extensive as cellular phone service in rural areas; in 2005, according to FCC mobile telephony data, virtually every county in the district had at least two cellular providers. But broadband appears to be on track to achieve that degree of coverage within a few years, judging by FCC statistics that track broadband availability by the number of providers serving subscribers located in each ZIP code.

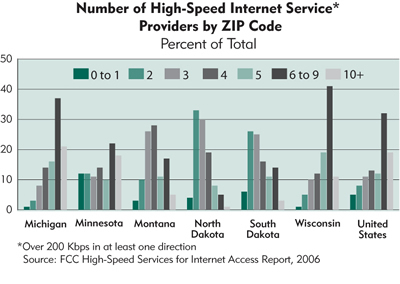

In 2002 every district state except Wisconsin trailed the national average in broadband coverage. Over half of the ZIP codes in North Dakota had no broadband subscribers; South Dakota wasn't far behind at 48 percent broadband-free; and in Montana 38 percent of ZIP codes had zero coverage. Today those blank spots on the district broadband map have largely disappeared (see chart). As of last June—the most recent data available—every district state had subscribers to at least one broadband provider in each of its ZIP codes, except for Minnesota, where 2 percent of ZIP codes (concentrated in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and on the Red Lake Indian Reservation) were bereft of broadband. The national average for uncovered ZIP codes was 1 percent.

No data exist on rural high-speed subscribership in each state. But FCC national data show that even in sparsely settled areas, over 96 percent of the population lives in ZIP codes with some kind of broadband service, defined by the agency as at least 200 kilobits per second (Kbps) in one direction.

However, the FCC has been criticized for setting such a low threshold for broadband; 200 Kbps can't hold a candle to the speed of cable modems (over 3 Mbps) or broadband technologies overseas.

And some researchers say that the ZIP code data overstate broadband availability. The presence of one or more broadband providers in a particular ZIP code doesn't necessarily mean that every residence or business in that area can receive high-speed service. Consumer surveys also suggest that rural broadband isn't as prevalent on the ground as it is on the FCC's maps. In the Minnesota Internet study, conducted by the Center for Rural Policy and Development in St. Peter, 22 percent of rural dial-up users said that broadband isn't available where they live. Only one in 10 Twin Cities dial-up users said that. A Pew national survey in 2004 found a comparable urban-rural split in reported broadband availability.

Nevertheless, the survey data show that a large majority of rural residents can get broadband today. What's more, broadband may be more available in rural areas than survey respondents think. "When people say, 'There's nothing available where I live,' it doesn't necessarily mean it's true," said Jack Geller, president of the Center for Rural Policy and Development. "It means that there's nothing that they're aware of."

Pick your platform

The extent to which broadband has permeated rural areas may be open to debate, but even a cursory survey of rural telecom markets in the district shows that private companies are providing high-speed Internet access on a variety of technological platforms, often bundled with digital TV, telephony and other services. Cable firms serve small communities, telephone companies sell DSL in and around towns, and fixed wireless and satellite services beam broadband to farms and clusters of homes deep in the countryside.

Large cable providers such as Charter Communications, MidContinent Communications and Mediacom are aggressively marketing the "triple play"—digital video, high-speed Internet and telephone service piped over hybrid fiber-coaxial lines. FCC data show that wherever cable TV is available, high-speed Internet access has followed as cable firms upgrade their infrastructure. In Montana 83 percent of households with cable could receive broadband last year; in Minnesota the figure was 91 percent.

Charter Communications' fiber-based backbone links hundreds of cable systems in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, giving subscribers in small cities and townships Internet access at speeds as high as 10 Mbps—over 150 times as fast as a dial-up modem. In the U.P., 97 of 102 communities served by Charter—including Chatham, a village of 250 people in Alger County—are wired for broadband, said Tim Ransberger, the firm's vice president of government relations for Michigan.

But as a rule cable service doesn't extend beyond municipal boundaries, because of franchise agreements and high capital costs. A cable operation must pass roughly 25 to 40 homes per mile to make installing physical plant in that area worthwhile, Ransberger said. "We raise our own capital ... and we have to pay that money back within a reasonable time frame."

DSL providers are in a better position to push broadband into outlying areas, because the basic fiber and copper infrastructure already exists, a legacy of decades of universal service subsidies, rural electrification loans and other government aid to rural telephone companies. Just about every small telco in the district offers DSL at various speeds, ranging from 384 Kbps up to 7 Mbps.

Randy Young, CEO of the Minnesota Association for Rural Telecommunications, a trade organization for rural telephone companies, said that its members have invested heavily in upgrading their networks to handle DSL and other broadband technologies, recognizing the revenue potential of high-speed Internet access,

video-on-demand and other bandwidth-hungry applications. "We're the logical [type of provider] in rural Minnesota to provide broadband," he said. "If we're not going to do it, nobody's going to. It's up to us to step up to the plate and spend the money."

That spending is implicitly subsidized by universal service funding, generally unavailable to cable firms. High-cost payments are meant to support local telephone service (see "Dialing for dollars"), but in practice, carriers are free to spend that money on fiber-optic cable and other infrastructure that make it easier to deploy DSL in remote locations.

In many rural markets, as in urban areas, the distinction between cable and DSL providers is blurring as telephone companies convert their copper networks to hybrid fiber-coax, allowing them to turn their own triple play. PrairieWave in Sioux Falls, S.D., is a "broadband overbuilder" that provides cable-speed Internet access over a far-flung fiber-coax network encompassing about 40 rural communities in southeastern South Dakota and Southwestern Minnesota. Last summer PrairieWave broadband became available in Jasper, Minn., a town of 600 people that until then had only limited DSL coverage.

A few ambitious rural carriers (and municipal governments, using their tax-exempt bonding authority) are deploying the ultimate broadband technology, fiber to the premises. Optical fiber run directly into a home or business can deliver speeds as high as 50 Mbps.

No wires required

Cable firms, telephone companies and other wireline providers dominate the broadband market in rural areas, just as they do in cities and suburbs. Cable modem or DSL lines accounted for over 83 percent of the high-speed lines in the six district states last year, according to the FCC.

However, wireless broadband vendors are gaining traction in rural areas. Wireless fidelity (Wi-Fi), microwave and other types of wireless service carried on licensed or unlicensed spectrum aren't as fast as cable or high-end DSL (most wireless services top out at about 1.5 Mbps downstream), but they work well in rural areas because there's no need for expensive wireline upgrades to reach isolated farms and settlements—just a small dish at each customer location, trained on a transmitter up to 15 miles away.

In 2006 wireless carriers reported 20,200 lines in Minnesota, an increase of 80 percent over the year before. The number of wireless accounts in Montana more than doubled to over 6,400 in the same period.

Rural fixed wireless providers in the district include Pasty.net in Calumet, Mich., which serves more than 20 communities in the western U.P., including tiny Copper Harbor at the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula; Sioux Valley Wireless, an electric cooperative subsidiary with 2,300 customers in the southeastern corner of South Dakota; and InvisiMax of Warren, Minn., operator of a Wi-Fi network that covers all or part of nine counties in northwestern Minnesota and northeastern North Dakota. InvisiMax's customer base has grown 15 percent to 20 percent annually over the past four years, said Vice President of Sales Phil Hebert.

For very remote, thinly populated areas where even fixed wireless isn't economical, there's always satellite service from companies such as Hughes Network Systems, SpaceNet and WildBlue Communications. Theoretically, satellites can deliver a broadband signal to a rooftop dish located anywhere in the continental United States. Two-year-old WildBlue has more than 120,000 subscribers nationwide and expects to broaden its rural reach with a new satellite that was slated to become operational in March. The Colorado firm has marketing agreements with AT&T, satellite TV providers DirecTV and EchoStar, and a number of telephone and electric co-ops in the district.

"You could make the argument that there's nobody without access [today], unless your house is in a cave," Geller said. "If you can get satellite TV, you can get satellite broadband."

Can you believe the price?

Yes, but can the average rural household afford broadband? Proponents of government subsidies for broadband say that high-speed Internet access may be unavailable for all practical purposes in some rural areas because it's too expensive. Pricey broadband becomes all the more expensive in rural areas of the district because average household income is lower than in urban areas.

Certainly satellite broadband costs more than the typical cable or DSL offering, in both monthly charges and upfront expense. WildBlue charges $50 a month for fairly slow broadband that can't support data-intensive applications such as Voice over Internet Protocol or video streaming, and installing a dish and satellite modem costs about $300.

Fixed wireless in remote areas can also be expensive, because of high deployment costs per subscriber. Last fall PrairieWave offered wireless high-speed Internet service in Ihlen, Minn., a town of about 50 homes that previously had only dial-up, for $49 a month. Perhaps not surprisingly, only four customers had signed up as of February. "This was a market test for me, and I can't say that I was thrilled with the results," said Joseph Galinanes, vice president of sales and marketing for PrairieWave. "Until the cost of the technology comes down, there's no way I can provide the service unless there's some subsidy to those rural homes."

However, focusing on satellite and wireless access—a very small slice of the rural broadband market—distorts the overall pricing picture. Getting an accurate read on broadband pricing is difficult because neither the FCC nor state utility and public service commissions tracks industry prices, and telecom firms increasingly "bundle" their high-speed Internet, TV and telephony offerings for one monthly price. But the best evidence indicates that rural charges for DSL, cable modem and even fixed wireless Internet access are roughly comparable with urban prices. And the Minnesota Internet survey suggests that rural consumers may actually pay less on average for their broadband. At the end of 2006, the average price of broadband in outstate Minnesota was $37.64 per month, almost a dollar less than the mean price in the Twin Cities metro area (although Geller cautioned that urban residents may be getting higher speeds for their money).

The Minnesota study also found that the average price of rural broadband had declined 19 percent since 2003, adjusted for inflation. That finding is consistent with national trends in broadband pricing; in the Pew home broadband survey, consumers reported that they paid about 16 percent less in today's dollars for service than they did in 2004.

At the tipping point

There's no doubt that large swaths of the district still lack access to fast, relatively inexpensive broadband that has become commonplace in urban areas. If you're a rancher on Montana's high plains or a resort owner in Wisconsin's north woods, your only broadband options may be fixed wireless or satellite, offering much less bandwidth for the buck than wireline technologies.

Also, more competition is needed in nonmetro areas to widen consumer choice and maintain downward pressure on prices. FCC data show a high proportion of ZIP codes in district states with subscribers to just one or two broadband services. In 2006 just two providers served 12 percent of ZIP codes in Minnesota; in North Dakota a duopoly controlled 33 percent of ZIP codes. Rural markets could benefit from competition among local exchange carriers that has cut DSL prices in cities and suburbs and more fixed wireless providers to challenge the dominance of cable and DSL.

But arguably the broadband market is working well enough in rural areas to render moot the current debate over universal service and other subsidies for broadband deployment. Aside from statistical and anecdotal evidence pointing to greater availability and lower prices in rural areas over time, the most compelling argument for not subsidizing broadband is the recent surge in broadband adoption by rural households. Rural broadband penetration reported in the 2006 Minnesota Internet study—two out of every five households—represents a 45 percent increase over the adoption rate a year earlier (see chart).

"Without any shadow of a doubt, broadband adoption is really taking off," Geller said. "If there is such a thing as a tipping point in the adoption of any new technology, it appears that we are either at that tipping point or past it. ...[Broadband] is really becoming a mainstream technology."

Earlier studies didn't measure broadband adoption in the Twin Cities metro area, so it's not possible to gauge whether the metro-rural broadband gap is closing in Minnesota. But Pew survey data show that nationwide, that gap is indeed narrowing. In 2003 rural household penetration was 9 percent, less than half the rate in urban areas. The 25 percent figure in the 2006 home broadband survey was considerably more than half the urban rate of 40 percent.

Despite these rural gains, the broadband divide that has led to calls for government intervention may stubbornly persist. Interpreting rural uptake rates for broadband is complicated by demographic factors that tend to depress broadband penetration in nonmetro areas.

On average, rural residents are older, less educated and poorer than city dwellers—all factors associated with lower Internet use and computer ownership. The Minnesota Internet study found that less than two-thirds of rural households in the state owned a computer, a prerequisite for Internet access; in comparison, over 71 percent of Twin Cities households had a computer. In addition, a higher proportion of rural residents state in Internet use surveys that they have no need for a computer, or Internet access. These socioeconomic factors help to explain why overall Internet connectivity, including fairly cheap dial-up, hasn't increased much in rural areas over the past five years.

In time, market forces in consort with demographic shifts will probably make high-speed Internet access as ubiquitous in rural areas as cell towers and big-screen TVs are today. Broadband is still a young technology, available to consumers only since the late 1990s. Other, now mundane technologies took over a decade to achieve 50 percent household penetration, even in urban areas—15 years for cell phones, 18 years for personal computers. As broadband technology improves and competition intensifies in an increasingly deregulated telecom market, prices are sure to fall further, even for fixed wireless and satellite service.

Today InvisiMax's cheapest broadband package costs $34 per month. "We think the magic number for high penetration is under $25 per month," Hebert said via e-mail. "As equipment prices drop and we reach further economies of scale, we see prices dropping."

Universal broadband?

The question facing policymakers is whether government should try to speed up broadband adoption in rural areas by subsidizing broadband deployment, as it did for electricity service and continues to do for local telephone service. Broadband subsidies wouldn't increase rural consumers' educational attainment or make them more computer savvy, but they could conceivably increase household penetration by underwriting infrastructure and operations costs in sparsely populated areas where telecom providers are loath to invest capital.

"I would assume that eventually the infrastructure will get there," said John Horrigan, associate research director for the Pew Internet Project. "It's a question of how long will it take, and whether forgone opportunities for people to use broadband during that intervening time period have social costs."

The universal service fund already supports the provision of broadband to schools and libraries (the E-Rate program) and to rural health care facilities on the grounds that some form of high-speed Internet access serves the common good, as do widespread telephone service and public education. If politicians decide that putting a high-speed connection in every home and small business also serves the public welfare, universal service funding could be extended to broadband, as Stevens' bill proposes.

But such a move stretches the notion of the common or public good; home broadband is a private service that mostly benefits individual users, not society at large. Explicitly subsidizing broadband deployment also risks driving up costs and fostering long-term dependence on government aid-the consequences of subsidies to rural providers of telephone service.

Alternative means of subsidizing broadband include beefing up and streamlining Rural Utilities Service loan and grant programs targeted at broadband deployment, discounting broadband service and computer purchases for low-income households, and giving federal or state tax breaks to broadband providers. A year-old Wisconsin law allows telecom providers that expand broadband service in areas with one or fewer broadband providers to claim sales tax credits on equipment.

Truly universal broadband will probably be achieved not through subsidies but through new technologies capable of bridging vast distances at lower cost than today's high-speed offerings. Two promising technologies in the experimental stage are WiMax and Broadband over Power Line (BPL).

WiMax, championed by Intel and already deployed in South Korea, Pakistan and Indonesia, can transmit data at over 10 Mbps for 30 miles or more—much farther than Wi-Fi. BPL delivers fast broadband service via the omnipresent electricity grid to wall outlets. Partly because of concern about interference with short-wave radio signals, electric utilities have been slow to roll out the technology in the United States. But commercial BPL systems are operating in Cincinnati and Manassas, Va., and in the district the municipal utility in Rochester, Minn., has conducted a trial of BPL service to homes and businesses.