On a warm July day, technicians and analysts working in a gray, nondescript building in St. Paul were beginning to sweat, but not from the rising heat. A power emergency was blooming on their computer monitors; as air conditioners in Ohio labored to cool homes and workplaces, the state was sucking in power like a black hole, driving down the region's reserves to perilously low levels.

An overburdened electricity grid was partly to blame for the power crunch, which potentially could have caused outages across a broad swath of the Midwest. Normally, utilities meet electricity demand with a combination of locally produced and imported power. Shipping in electricity from other parts of the country via long-distance transmission lines may be cheaper than generating or buying power locally. But when electricity demand peaks—typically in hot weather, but occasionally in the winter as well—transmission bottlenecks can restrict the flow of electricity, limiting the ability of utilities to slake their customers' thirst for power. On July 9, sufficient power was being generated in the Midwest to meet demand in Ohio, but it couldn't reach its destination.

"Between the generation that is physically placed in this region and the ability to import power, those two things added up still weren't quite enough," said Clair Moeller, vice president for transmission asset management at the Midwest Independent Transmission System Operator, a power industry organization that oversees the transmission system in the eastern two-thirds of the Ninth District.

To avert the possible power failures, MISO sent an energy emergency alert to member electric utilities, asking them to be prepared to fire up every available generator, exercise interruptible-power contracts with businesses, make public appeals to conserve power use and take other steps to prevent the grid from crashing. By the next day, the Buckeye heat wave had abated, ending the crisis—surely not the last that MISO and utilities will face. A more serious power crisis occurred in August 2006, when soaring electricity use across the eastern United States, exacerbated by transmission bottlenecks, came close to triggering rolling blackouts.

The nation and the district have a serious transmission problem. Chokepoints—what electrical engineers call capacity constraints—pepper the grid, the result of steady increases in long-distance power flows and 25 years of scant investment in new transmission. "There's a physical limit to how much energy you can import, and we call it congestion," Moeller said.

This congestion is more than an inconvenience for district utilities and their customers. Like traffic-snarled roads or jets stacked up over an airport, clogged transmission lines exact an economic toll and make life a little less safe.

Transmission bottlenecks make the power supply less reliable, reducing the productivity of businesses and potentially compromising public safety. And consumers in the district face a threat that is less obvious but no less harmful: higher prices, because congestion forces utilities to buy power from the closest available source, often at a premium. That's the case in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where consumers often pay more for electricity than in other district states. Constrained transmission also stands in the way of development of additional generation, including new cleaner-burning coal plants and a multitude of wind power projects.

The good news is that investment in regional transmission—the high-voltage lines that link utility service territories—appears to be picking up in the district, although Wisconsin and Minnesota are seeing more actual construction than other states. In the past five years, a need to transport more power to serve customers, combined with a push by energy regulators for more regional transmission, has encouraged utilities and stand-alone transmission companies to undertake major projects that they once avoided.

Large regional transmission projects under construction or proposed in the district include new lines in southwestern Minnesota that will allow more wind power to get to market; Arrowhead-Weston, a 220-mile line stretching from northeastern Minnesota to Wausau, Wis.; CAPX2020 (Capacity Expansion by 2020), a multibillion-dollar effort by a consortium of utilities to build a series of high-voltage lines across Minnesota; and Northwestern Energy's plan to build an $800 million line from southwestern Montana into Idaho.

But not all of the transmission capacity on the drawing board may get built, given the complexities of routing and paying for large transmission lines.

Strain on the backbone

High-voltage transmission lines are so much a part of the landscape that they become invisible, unless they happen to run past your back yard. Strung on steel towers up to 150 feet tall, long-distance lines—generally those rated at 230 kilovolts (kV) or higher—carry electricity from generating plants to distant cities and towns. Local substations step down that power to a lower voltage and direct it via smaller lines to homes, offices and factories. Often likened to interstate highways, major transmission lines tie together local networks owned by individual utilities and transmission companies.

This transmission backbone has made possible the development of a national wholesale or bulk market for electricity. Beginning in the early 1990s, federal deregulation broke the long-standing monopoly utilities held over power production and transmission. New rules issued by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) granted independent power producers access to the transmission grid for the first time. Regulatory unbundling of generation and transmission assets led to the formation of transcos, companies dedicated to building and operating long-distance transmission lines. "We are the keepers of the high-voltage network in our part of the world," said Mark Williamson, vice president of major projects for Milwaukee-based American Transmission Co. (ATC), which is building the Arrowhead-Weston line.

Enormous volumes of electricity flow back and forth on this network in response to marginal price differences, maximizing transmission efficiency and driving down the overall cost of electricity. Utilities seek the cheapest power available to resell to their customers; if power produced by a Minnesota utility's own generators costs more than juice produced in Texas, the utility will try to import the power from Texas over long-distance transmission lines.

FERC-administered regional transmission organizations such as MISO have arisen to orchestrate this massive, ceaseless flow of power. MISO, covering 15 states and the Canadian province of Manitoba, manages one of the world's largest wholesale energy markets, clearing more than $2.2 billion in transactions monthly. Formed in 2005, the MISO market functions like a commodities exchange, with open trading between power producers and resellers based on location-specific prices that change by the hour. Similar but less formal trading arrangements among generators and transmission owners direct power flows outside MISO's footprint, in parts of the Dakotas and central and western Montana.

Transmission constraints diminish the benefits of free-flowing electricity, restricting the ability of utilities to pipe in power from other areas of the country on demand. While not as dire as the electrical gridlock gripping other areas of the country—a 2006 study by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) identified southern California and the Atlantic Seaboard south of New York as "critical congestion areas" in urgent need of relief—significant congestion exists within the district or just outside its borders.

These bottlenecks include a tight spot in northeastern Iowa that restricts imports into southern Minnesota; a shortage of lines in southwestern Minnesota that limits exports of wind power; a long-standing barrier to eastward power flows in the Red River Valley; and weak transmission on Wisconsin's fringes that squeezes the flow of power into eastern Wisconsin and the U.P. (see map). Numerous smaller constraints within utility service areas cause headaches for utilities and independent generators trying to wheel power through the region.

Several interrelated factors have contributed to increasing congestion on key pathways for electricity across the country and in the district.

Market-driven, computer-guided power trading has increased efficiency (since 2005, unused transmission capacity on the MISO network has dropped from 10 percent to less than 2 percent), but a surge in regional power flows since the 1990s has strained a tenuously interconnected grid. Long-distance transmission lines built after the disastrous Northeast Blackout of 1965 were only meant to link local utility territories in times of emergency.

Meanwhile, investment in transmission infrastructure has lagged for a number of reasons. Resistance by local communities and environmental groups to construction of new lines in many areas dragged out already lengthy review by state agencies, discouraging utilities from proposing projects. Delayed by battles over environmental permitting and property rights, the $400 million Arrowhead-Weston line has taken 10 years to build.

NIMBYism combined with uncertainty about who was responsible for building new long-distance lines in a rapidly changing regulatory environment turned off investors who were more interested in the Internet and biotech anyway. As generation capacity increased and the wholesale electricity market took off in the 1990s, the power industry paid little attention to transmission. "The transmission piece just got neglected," said Jason Makansi, a St. Louis expert on electrical systems who has written a book about the overtaxed national grid. "People just assumed that it was going to be there, that it was adequate."

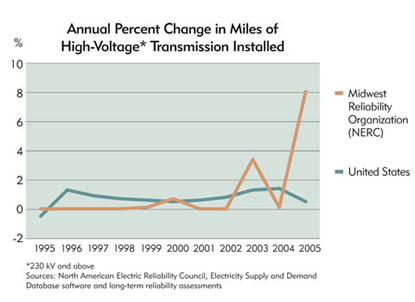

The North American Electric Reliability Corp., an industry organization responsible for the security of the bulk-power system, tracks annual construction of long-distance transmission lines, those rated at 230 kV and above. Nationally, the number of circuit miles (a measure of power-carrying capacity per mile of line) increased less than 1 percent a year between 1994 and 2002. In a NERC territory that encompasses the eastern two-thirds of the district, transmission growth was virtually flat during the same period; only 120 circuit miles were added to the grid (see chart).

Congestion toll ahead

In this part of the country, widespread power outages like those that struck California in 2001 and the Northeast in 2003 are rare, although MISO emergency alerts are a reminder that transmission bottlenecks pose a threat to electrical reliability. Much more commonplace is a largely overlooked consequence of overtaxed long-distance transmission—higher electricity prices. When electricity use surges, limits on power imports caused by transmission constraints force grid operators to call upon higher-cost local generation to meet demand, an operation called redispatch. Essentially a congestion fee, redispatch cost is passed down to ratepayers on their monthly bills.

Last year the aggregate cost of congestion in MISO's territory was $500 million—a premium that consumers would not have paid if transmission constraints did not exist. Congestion cost data are not available for individual states within MISO, but a look at energy market prices shows that ratepayers in a few district states bore a disproportionate share of those costs. They live on the wrong side of transmission bottlenecks that deny them access to cheap imported power at peak times.

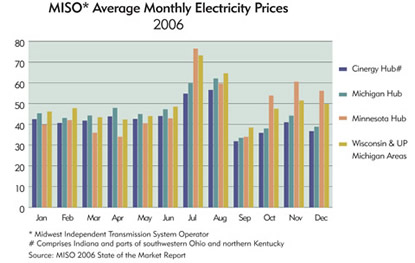

MISO price data show that during the second half of 2006, average monthly electricity prices in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the U.P. were consistently higher than those in lower Michigan and Indiana (see chart below), mainly because of congestion on lines into southern Minnesota and eastern Wisconsin. Insufficient incoming transmission is of particular concern in Wisconsin, said Scot Cullen, chief engineer at the state Public Service Commission's gas and energy division: "Wisconsin for a long time has been a net importer of energy, so you need to be able to transmit power from generators in Wisconsin but also bring in what you need from other areas."

Hemmed in by Great Lakes to the north and east, Wisconsin depends on power shipped in from Illinois, Minnesota, the Dakotas and beyond. But there simply aren't enough high-voltage lines coming into the state from the south and west, Cullen said. These bottlenecks also restrict the flow of power north into the U.P., inflating prices there relative to other MISO states.

Other transmission constraints in the district stand in the way of development of new power sources such as clean-burning coal plants and wind farms. Minnesota, Wisconsin and Montana have enacted renewable-energy mandates intended to foster homegrown, green power production (see the July 2007 fedgazette), but that power won't reach urban markets unless transmission capacity is increased in rural areas. The DOE study identified Minnesota, the Dakotas and Montana as "conditional congestion areas"—regions where major investments in backbone transmission are needed to realize the potential for large-scale coal and wind generation.

On the Buffalo Ridge in southwestern Minnesota, where hundreds of wind turbines have sprouted in the past 20 years to harvest strong westerly winds, tapped-out transmission has put a number of wind farm proposals on hold. As of August, wind developers had filed interconnection requests with MISO totaling 8,000 megawatts (Mw) by 2009—roughly 20 times the area's current transmission capacity.

A much larger constraint called the North Dakota Export Boundary (NDEX) puts a damper on future wind and coal development in other parts of western Minnesota, the Dakotas and eastern Montana. This bottleneck, affecting a broad region stretching roughly from the Manitoba border south to Sioux Falls, S.D., caps eastward power flows at roughly 2,000 Mw; more coal and wind generation west of this zone destined for Minneapolis-St. Paul and other Midwestern load centers would likely exceed that limit.

Electricity suppliers in Montana face a similar obstacle to increased exports to power-hungry markets in California and the desert southwest: a persistent transmission constraint in Washington state that impedes westward power flows.

Transmission rebirth

While the grid strains to cope with the increasing demands being placed upon it, there are signs of a resurgence in regional transmission investment in the district. In fact, recent NERC data indicate that transmission construction is increasing at a faster pace in the district than in the country as a whole. While national circuit mileage increased only slightly from 2002 through 2005, circuit mileage in NERC's Midwest region during that period increased at about 4 percent annually.

In addition to already installed lines, hundreds of circuit miles of additional transmission in the district are under construction or planned by individual utilities, power consortiums or transmission firms. MISO's transmission expansion plan for the western part of its footprint, which covers most of the district, lists $2.3 billion in approved construction and upgrades through 2011 (although not all of that projected spending is earmarked for regional transmission). NERC estimated in 2005 that close to 1,400 circuit miles of 230-and-above kV transmission would be built in its Midwest region by 2010.

Why the renewed interest in building long-distance transmission now, after a quarter century of neglect? Self-interest is one powerful impetus, said Moeller of MISO. In open competition with other power producers under FERC deregulation, utilities must woo customers by delivering the cheapest power available. Importing power requires either building long-distance lines or paying somebody else to do it through transmission fees. Getting a line approved and built may be an expensive and drawn-out process, but the alternative—losing power contracts—is worse. "For all the difficulties [producers] have in getting permission to construct, it's increasingly more important for them to move energy," Moeller said.

Additional pressure and incentives to invest in transmission infrastructure are coming from regional planning organizations. MISO, for example, has encouraged transmission owners to address physical constraints, although it cannot mandate construction.

MISO recently introduced a cost-sharing formula that promises to solve a conundrum that has long bedeviled long-distance transmission projects: how to divvy up the cost of a line that spans a number of utility service areas. Whose ratepayers should ultimately pay for a new line piping power from South Dakota to Wisconsin, and in what proportion? Cost-sharing mitigates this problem by spreading 20 percent of the costs of large projects among all MISO members.

New laws have also greased the wheels for new transmission, making investment more lucrative and the permitting process less onerous. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 sweetened the pot for investors in new transmission lines. FERC orders finalized last year make utilities and transcos that undertake transmission projects eligible for higher rates of return on equity. Those higher wholesale rates would be passed along to ratepayers in state utility rate cases. "There was a feeling in our industry that the FERC needed to do more to provide appropriate incentives for building out the transmission system," said Jim Owen, a spokesman for the Edison Electric Institute, an association of investor-owned utilities. "To some extent, the FERC has done that."

States have also made it easier for transmission investors to get their money back. A 2005 Minnesota law lets utilities bill their customers annually for transmission construction instead of waiting until the project is finished; Montana slashed property taxes 75 percent on transmission lines carrying power from "green" sources such as renewables or clean coal.

Other regulatory changes at the state level aim to expedite the process of establishing the need for proposed transmission lines and approving routes. In Wisconsin, a 2003 law shortened the review process by requiring the Public Service Commission and the Department of Natural Resources to review transmission applications concurrently rather than consecutively. Today the agencies must pass judgment on a project within a year—less than half the time the review process used to take.

Highways in the air

Whatever the forces at work, the stars seem to be aligned for the development of new transmission in the district. Towers are rising into the air, and utilities and transcos seem committed to erecting more (see table).

Xcel Energy is in the midst of a $265 million, multistage project designed to relieve constraints in southwestern Minnesota blocking the flow of wind energy to the Twin Cities and other markets in Minnesota and South Dakota. Some line segments and substations are already built; others are slated to go into service next year and in 2009. The project includes an 86-mile, 345-kV line linking substations near Lakefield, Minn., and Sioux Falls, S.D., and five shorter, lower-voltage lines connecting substations on the Buffalo Ridge with other Xcel nodes on the grid.

When complete, the improvements—which are eligible for pay-as-you-go cost recovery under the 2005 legislation—will almost triple transmission capacity on the Ridge to 1,250 Mw, said Patti Nystuen, a spokesperson for Xcel. Still more transmission investment is needed in the area; according to MISO, the Xcel upgrades will provide only about 10 percent of the additional capacity needed to satisfy pent-up demand from wind developers.

In Wisconsin, ATC is building the last few miles of the Arrowhead-Weston line, a joint project with utilities Minnesota Power and Wisconsin Public Service Corp., that promises to alleviate a severe constraint on power flowing into Wisconsin from Minnesota and the Dakotas.

ATC was created in 2001 by state legislation that also required utilities in eastern Wisconsin to divest their transmission assets. In the past two years, the company has broadened its focus from upgrading local transmission acquired from utilities to regional projects such as Arrowhead-Weston, designed to not only improve reliability but also open the door to competition from low-cost generators located outside the state. Scheduled for completion early next summer, the 345-kV line will function as "a real highway for lower-cost power transactions," ultimately lowering electricity bills for Wisconsin residents and businesses, Williamson said.

Other ATC projects intended to relieve transmission bottlenecks include a 110-mile connection between the western U.P. and northeastern Wisconsin that went into service last summer and 90 miles of new and upgraded lines along the Wisconsin-U.P. border slated to come online in 2010. Both projects will allow utilities using ATC's lines to import greater amounts of lower-cost power into the U.P.

The firm stands to profit from its transmission investments. Like all transcos that came into being under wholesale deregulation, the company's rates are set by FERC instead of state utility commissions. Under a 2003 tariff agreement, ATC is entitled to a 12.2 percent rate of return on equity, which it collects from utilities during construction as well as after the line is built. That rate is almost 2 percentage points higher than the average ROE awarded to state-regulated utilities in 2007, according to Edison Electric financial data.

Thinking big

Other regional transmission projects in the district are in a formative stage, weighing route options and lining up financing while preparing to run the regulatory gantlet.

Xcel, Great River Energy and nine other utilities have put their collective financial and marketing muscle behind CAPX2020, an ambitious program to build over 600 miles of high-voltage transmission lines in Minnesota and parts of Wisconsin and the Dakotas. Last summer, the utilities filed a formal proposal with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission for the $1.6 billion first phase of the project and mailed notices to over 70,000 landowners along planned routes.

The main driver for CAPX2020 is a healthy appetite for power in rapidly growing areas of Minnesota such as the Twin Cities, St. Cloud and Rochester. Four lines to be built by 2014 would increase load-serving capacity in those areas. But at least two lines would also help loosen transmission bottlenecks, said Terry Grove of Great River Energy, co-leader of the project.

A 200-mile, 345-kV line running between Brookings, S.D., and the Twin Cities would pass through the Buffalo Ridge, boosting transmission capacity in the area to about 1,900 Mw. And another line from Fargo, N.D., to the St. Cloud-Monticello, Minn., region would ease the NEDX constraint somewhat, providing a bigger conduit for exports of coal-fired and wind power from the Dakotas.

Three long-distance transmission projects are planned in Montana, where generators and power marketers are pressing transmission owners for more export capacity. The proposed lines are eligible for FERC's investment return sweeteners.

Northwestern Energy announced in June its plans to build a 500-kV transmission line that would open a path to new markets in the Sunbelt. The Mountain States Transmission Intertie (MSTI) would avoid congestion on lines to the West Coast by routing power southwest into Idaho, where it would continue on existing or planned lines to customers in Nevada, Arizona and southern California. Northwestern, which owns no generation, is selling capacity on the future line to power producers under an "open season" or subscription process used for gas pipeline development.

Dave Gates, the company's vice president of wholesale operations, sees this approach as one solution to the chicken-and-egg problem created by the splitting of generation and transmission assets in Montana and other states under deregulation. "Without transmission, nobody's going to build generation, and without generation, nobody's going to build transmission, so it has to be done hand in hand," he said. "We're trying to facilitate that with [MSTI]."

The other Montana lines, both in the early stages of official review, have been proposed by Canadian transmission companies eager to break into markets south of the border.

Montana Alberta Tie Ltd. (MATL) is pushing a $120 million cross-border link between Great Falls and Lethbridge in Alberta, a province with surplus coal-fired and wind generation available for export. If approved by Montana's Department of Environmental Quality, DOE and Canadian regulators, the MATL would pipe that power south—conceivably lowering electricity bills in Montana—and give developers of new wind farms in the north-central part of the state access to Canadian buyers.

TransCanada Corp., a Calgary-based energy conglomerate, wants to construct a large-capacity line stretching hundreds of miles from Montana to Las Vegas. The $1.2 billion-plus project would keep the city's neon shining after 2012 with Montana power produced by coal-burning plants, and wind farms if more are developed over the next decade.

Miles and miles to go

Even if all the regional transmission lines proposed within the district and on its borders are built, billions of dollars of additional investment will be needed to maintain the reliability of the grid and prevent price hikes due to congestion. By 2011, MISO expects new transmission planned in northeastern Iowa to relax the constraint on power headed north into Minnesota. But all indications are that well into the next decade, bottlenecks will still impede the flow of power off the Buffalo Ridge, from the Dakotas into Minnesota and westward from Montana.

Moreover, it's likely that new constraints will develop as rising electricity consumption in the region and the country as a whole pushes current transmission capacity to its limits. A rule of thumb in the power industry holds that electricity use increases in lock step with gross domestic product—historically 2.5 percent to 3 percent annually.

Forecast demand for the Upper Midwest tracks the national trend line: A 2005 study for the CAPX2020 initiative estimated that electricity use in the project area, which encompasses Minnesota and large chunks of Wisconsin, the Dakotas and Iowa, will increase about 2.5 percent a year through 2020, adding about 6,300 Mw in generation to the regional grid.

Distributed generation—developing power sources close to where electricity is consumed—and cutting demand through conservation and efficiency initiatives have the potential to take pressure off the grid. But while such strategies may reduce the need for more hulking towers marching toward the horizon, they're not likely to eliminate it entirely. For example, developing small-scale, local generation without investing in new backbone transmission risks Balkanizing the grid further, preventing efficient power producers from selling excess power to the highest bidder.

If the recent trend toward increased transmission investment is to continue, regulators have their work cut out to find ways to fairly allocate costs for new long-distance lines and to streamline state permitting processes. The power industry is still only partially deregulated, subject to a confusing hodgepodge of federal and state oversight. "We're in the shift zone between the old paradigm of being a fairly local regulated monopoly, to the new place that has a vibrant wholesale exchange of energy," Moeller said.

A regional policy group called the Organization of MISO States was formed in 2003 to promote concerted regulatory action among FERC, MISO and state utility commissions in the MISO region. Achieving consensus on transmission planning and siting is high on the organization's agenda.

As for utilities and transcos, the onus is on them to make their case that new or upgraded transmission lines are necessary and to ensure that property rights and the environment receive due consideration during planning and construction. Protests against the Arrowhead-Weston line died away two years ago, and other lines under construction or planned in the district have not yet provoked organized resistance. But with big transmission projects, every public hearing is a potential flashpoint for opposition that can delay or quash a project.

"I don't think anyone would disagree with the proposition that siting a major multistate or interstate transmission line is difficult," said David Meyer, a senior policy adviser in the DOE's Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability.

In Montana, farmers in the path of the MATL project have complained about diagonal crossings of farm fields and about plans to erect H-frame towers instead of more tractor-friendly single poles. And Northwestern Energy, fearful of raising the hackles of the Audubon Society and other environmental groups, is taking great pains in routing the MSTI line to avoid disturbing the breeding grounds of the greater sage-grouse, a denizen of the high plains under siege from development in the West.