Economic fortune has smiled on Montana in recent years. An oil boom has pumped revenue into the eastern part of the Treasure State, while a strong mining sector and an influx of wealthy residents from other states have enriched communities in the west.

However, this prosperity hasn't trickled down to the state's teachers. Low pay relative to other states is making it harder for school districts, especially smaller ones, to recruit and retain teachers. "We are at a crisis level," said Jack Copps, superintendent of the Billings Public Schools. "There is a growing number of small schools that advertise and receive no applicants for positions at all."

Colleges in the state are also struggling to hire and keep instructors who can earn higher salaries elsewhere. Last fall, a Montana University System recruitment and retention task force found that universities were having trouble attracting and keeping students because of an inability to hire sufficient staff. Some programs were in danger of losing accreditation. Compensation for teachers and support staff was a primary cause of these problems, the panel concluded. It recommended making pay more competitive to avoid further declines in academic and service quality.

Antagonists on different sides of the education reform issue will claim either that teachers are paid too little or that they are bleeding public coffers. An analysis of teacher salaries in the district shows that such generalizations aren't very useful. How much teachers get paid varies greatly by state: In some, they earn salaries close to the national average for their profession, while in others, salaries rank among the lowest in the country.

Differences in median incomes among states explain much of this striking divergence in teacher pay within the district. But that's not the whole story. A look at income trends over the past 15 years suggests that teacher pay in western district states hasn't kept pace with their neighbors.

The great divide

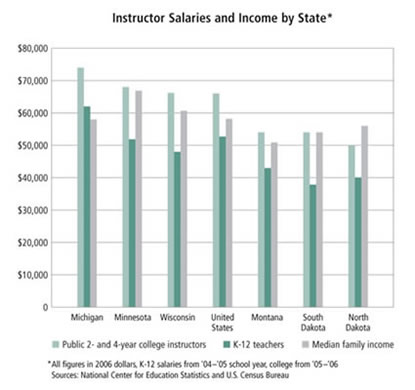

The distribution of instructor salaries (see chart) shows a wide geographic rift in the district. In the Great Lakes region—Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin—most elementary and high school teachers earn a middle-income salary, while postsecondary salaries are about 25 percent higher. In these states, teacher pay hovers near the national average for all teachers. In contrast, in the western district states of Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota, salaries for instructors at both the college and K-12 levels run at least 20 percent below the national average.

Present differences among states in teacher pay hold at all education levels. The average salary for full-time teachers in public postsecondary schools is highest in Michigan, followed by Minnesota, Wisconsin, Montana, South Dakota and North Dakota. The rankings are nearly the same for grade school and high school teachers, with the two Dakotas switching places at the bottom.

The pay spread within those rankings is considerable. Average college instructor pay in 2006 was $73,103 in Michigan, according to the U.S. Department of Education. That's 43 percent higher than North Dakota's average postsecondary pay of $51,140. The national average was $67,951. The picture is similar at the K-12 level; Michigan's average teacher salary of $57,814 in 2006 was 64 percent higher than South Dakota's average.

Over time, the east-west rift in the district in K-12 teacher pay has narrowed slightly. In the eastern states, average salaries adjusted for inflation fell from 1990 to 2005; in Wisconsin, average salaries fell 10 percent. During the same period, pay increased in the western district states, with South Dakota seeing the most growth at nearly 6 percent.

Despite a slight convergence since 1990, a sizable gap remains between teacher salaries in the western and eastern parts of the district. A closer look at incomes for all families in the district puts it in perspective.

Behind the curve

One obvious explanation for differences in teacher pay among states is that all incomes are different. State income comparisons provide a proxy for relative costs of living. Since incomes are higher in the eastern district states than in the western states, why should teacher pay be an exception?

In fact, as the above chart indicates, the income disparity between east and west roughly fits the pattern of teacher pay in the district. Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin all have median incomes near the national figure, while incomes in Montana and the Dakotas are somewhat lower than the national average.

So the fact that teachers get paid less in the western part of the district should not be a surprise, given that almost everyone makes less there. However, the magnitude of the gap is much greater for teachers, suggesting that they are a special case.

For example, Michigan's 2005 median family income was almost 8 percent higher than South Dakota's, not nearly as large a difference as the 64 percent gap between the two states in average K-12 teacher salaries. Lest one conclude that Michigan is a high-paying outlier, consider that Minnesota's median income is 24 percent higher than South Dakota's, while its K-12 teachers are paid 38 percent more. This is a closer correspondence than the comparison with Michigan, but there's still a bigger gap than would be expected from looking at incomes.

The same unexpected gap holds for the college level. Instructors at public two-year and four-year institutions in Minnesota make 36 percent more than in neighboring North Dakota, a much larger difference than the 21 percent difference in median incomes.

Furthermore, despite the growth in teacher salaries in the western district states since 1990, their incomes have grown much faster. For example, South Dakota's median income in 1990 was 34 percent lower than Minnesota's. Since then, median income in South Dakota has grown 17 percent faster than in Minnesota, while the gap in teacher pay has closed only slightly.

Teacher salaries in the western district states haven't converged with pay in eastern states in the way that growth in state incomes over the past 15 years might suggest they would. There are a number of possible reasons income growth for teachers appears to have lagged in these areas. But such compensation issues can have important consequences for the quality of education.

Where the grass is greener

Teaching is a field that sees a lot of turnover. Nationwide, 15 percent of new teachers leave the profession after their first year. One reason for that is ability; not everyone is cut out for the work.

But pay is an important factor. A 2005 study by two economists at Montana State University found that Montana's lowest-paying districts experience significantly more recruitment and retention problems than other districts, even controlling for geographic isolation. Teachers expect a minimum level of pay to cover the bills and retire college debt, and they're willing to go where the money is.

A recent report by the Montana Department of Education found that 40 percent of graduates from the state's teacher education programs are leaving the state to work elsewhere. In turn, high teacher turnover rates and recruiting problems are believed to hurt student performance because they result in larger class sizes and a less stable classroom environment.

It's hard to say exactly what teacher pay should be, and looking at median incomes might not be much of a guide. But difficulty hiring and retaining teachers could be a market indication that pay is too low. How best to use limited public resources is always a difficult decision for state and local governments. However, given the high returns to education, state and local governments might think twice about offering competitive teacher salaries.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.