Tired of being squeezed in a middle seat on an airplane? No place for your carry-on luggage? Boarding and deplaning take forever? Here's a way to avoid all that: Move to an EAS city.

When Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act in October 1978, it also created the Essential Air Service (EAS) program to ensure that small cities would not be abandoned by air carriers seeking more profitable routes. The program subsidizes airlines willing to serve isolated communities.

When Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act in October 1978, it also created the Essential Air Service (EAS) program to ensure that small cities would not be abandoned by air carriers seeking more profitable routes. The program subsidizes airlines willing to serve isolated communities.

While that sounds good on paper, the program has remained essentially unchanged since its inception despite changing demographics and aviation economics. What was once a program to improve accessibility for remote regions is more often today considered something of an entitlement program for locations accustomed to artificially cheaper air service.

EASy does it

At the end of 2007, 19 communities in the Ninth District were involved in EAS, or about one in five designations in the lower 48 states (see map of EAS district locations). Brookings, S.D., was put on temporary hiatus in 2007, but is hoping to return and was included as an EAS site for this analysis. Pierre, S.D., was also part of the program, but exited voluntarily in 2006.

Populations in these district EAS communities range from 20,000 in Watertown, S.D., to 1,200 in West Yellowstone, Mont., which has only seasonal service from June through September. Eligible communities must have had air service at the time of deregulation in the late 1970s and also had to be at least 70 miles from a medium- or large-hub airport.

EAS airports also have to find an airline willing to provide at least two daily flights, six days a week. The incentive for airlines is a federal subsidy for providing the service, calculated using passenger and revenue projections against related cost. The subsidy fills the operating difference, plus a 5 percent profit margin. Subsidies are capped at $200 per passenger, unless the community is more than 210 highway miles from the nearest medium- or large-hub airport, at which point there is no subsidy cap. All EAS communities in the district exceed the 210-mile standard because the airports used to gauge air accessibility are in Denver, the Twin Cities and Milwaukee.

Total subsidies for air service to any single community are not particularly great in the scheme of federal spending, ranging from about $247,000 in West Yellowstone to almost $1.7 million in Dickinson, N.D. Added up, the 19 EAS communities in the district received almost $19 million in 2007, double the $9 million in assistance received in 1998. Nationwide, annual EAS subsidies have grown at a roughly similar rate and were about $110 million last year.

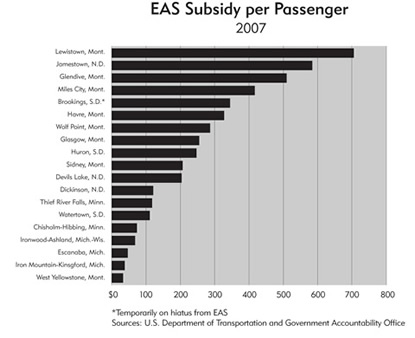

In passenger terms, EAS subsidies vary widely, ranging from $32 per passenger at West Yellowstone to more than $700 for every person flying into or out of Lewistown, Mont. (see chart). Eleven of the district's 19 EAS communities had average passenger subsidies last year that exceeded the $200 benchmark, including the large majority in the Dakotas and Montana.

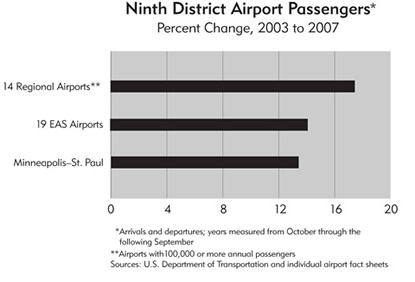

Passenger trends at EAS airports are difficult to nail down, but they appear to be doing fairly well of late as a group, at least in the district. Federal data are incomplete prior to 2003 because data were not collected for planes with 60 or fewer seats, and such planes are common at small airports. But from 2003 to 2007, federal Department of Transportation data show that passenger growth at district EAS airports increased an estimated 14 percent, though divergence among individual airports is evident. (Available data on small airports also have some built-in wiggle; for example, figures from a DOT database are rounded to the nearest thousand for years 2003 to 2005, and many EAS airports handle only a few thousand passengers annually.) In fact, this estimate puts EAS passenger trends roughly on par with passenger trends at larger regional airports and slightly faster than at Minneapolis-St. Paul International, the biggest airport in the district by a factor of more than 30 (see chart).

But the total number of arriving and departing passengers in all 19 district EAS airports is tiny—just 135,000 passengers last year, about the same number handled at Sawyer International Airport, the largest airport (and non-EAS) in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. An EAS designation requires two flights daily from the local airport, and those flights rarely leave full. The most extreme case: Last year, twice a day, six days a week, a 19-seat plane took off from the EAS airport in Lewistown, Mont. On average, each plane had just over two passengers.

Mile-high intentions

The program's intent is to bridge air accessibility problems in remote communities. Debbie Alke, aeronautics administrator for the Montana Department of Transportation, said that eastern Montana relies heavily on the EAS program.

"When you talk 'essential,' it truly is," said Alke. That part of the state has "no trains, no buses, and most people in the eastern communities fly to Billings for banking, legal work and medical appointments." She added that Sidney is in the midst of an oil boom, and businesses routinely ask about convenient air service to the region.

Brookings is on a temporary hiatus from the EAS, pending approval of special legislation. But according to Mike Wilson, Brookings airport manager, people like the convenience and the free parking and look forward to service returning to that community. "It's nice to have service here and at an affordable rate" that EAS enables, Wilson said.

What's difficult to assess is the appropriate level of subsidized air access. The program's own definition of remoteness has not changed since its inception, all but ignoring fast-growing regional air markets. That might seem like a minor design matter, but it creates perverse choices for local air travelers. For example, residents of Hibbing, Minn., can fly direct to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport, but the city is a mere 39 miles from Duluth, which has several flights each day to the Twin Cities as well. The kicker: A check with online airfare brokers showed the Hibbing flight was slightly cheaper.

Although Brookings lies about 220 miles from the Twin Cities airport, it is only about 50 miles from the Sioux Falls (S.D.) Regional Airport, from which travelers can choose nine hub cities via four airlines, and where passenger travel has grown by more than 30 percent since 2003. Total passengers through Brookings have been rising, but numbered just 3,500 in 2007—the passenger volume of about one-and-a-half days in Sioux Falls.

Or say you're in Escanaba, in Michigan's U.P., and want to get to Milwaukee or Minneapolis. Despite the fact that the community lies about 60 miles from Sawyer International Airport near Marquette—which handles roughly seven times the passenger volume—EAS subsidies help make it cheaper to fly out of the Escanaba airport for both big-city destinations.

Although eastern Montana is truly remote, some EAS location curiosities exist even there. For example, Sidney is an EAS community of about 5,000 near the eastern border with North Dakota. The closest airport of even moderate size is Bismarck, N.D., about 250 miles away. But there are also EAS airports in Williston, N.D., about 55 miles to the northeast, and Glendive, Mont., about 50 miles in the other direction.

That might sound like a long distance, but when you consider air accessibility in terms of time, a 60-mile trip on lightly traveled roads likely takes less time—home to boarding—than most air travelers in the Twin Cities are afforded when traffic, parking and tighter security are considered.

Just plane leakage

Given the relative proximity of EAS airports to larger airports and other EAS airports, it's hard to pin down exactly what the program achieves in terms of air accessibility; few EAS communities are truly remote, and in many cases regional airports are within a reasonable distance.

While passengers of EAS flights undoubtedly like the comparative convenience and affordability, the broader airline market is not necessarily better off. EAS airports likely offer some useful competition to larger regional airports that lie in relative proximity, which hypothetically should keep prices in check. At the same time, without nearby EAS flights, passenger loads at regional airports would likely increase, which should lead to more and better service.

Keith Kaspari, manager of Sawyer International Airport, said the airport sees passengers from Escanaba and Iron Mountain (another EAS airport in the U.P.) and is slowly grabbing more market share. From 1999 to September of last year, Sawyer's share of all U.P. commercial passengers went from 37 percent to 53 percent; annual passenger totals increased by one-quarter.

One simple reason is choice: Sawyer offers flights to four hubs (Minneapolis-St. Paul, Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee), whereas EAS airports are often limited to one or two destinations. Sawyer flights are typically in larger and more comfortable airplanes as well. Kaspari said that his airport's greatest competition is Green Bay, Wis., which offers larger aircraft and historically lower fares, so much so that even with an overnight hotel stay, it's often cheaper for a family to drive to Green Bay for some flights.

Government reports have questioned the EAS's utility. In a 2006 assessment, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) gave the program a "not performing" grade, noting it has "remained fundamentally unchanged in the more than 25 years since [its] inception, while the aviation landscape has changed dramatically, especially with respect to the development of the hub-and-spoke systems, the growth of regional jets, and the expansion of low-fare service by low-cost carriers." It recommended that the program serve only the most isolated communities and cited data that show passengers are willing to drive to a nearby major hub with a low-fare carrier.

Whether such recommendations are implemented is likely based more on political decisions than economic ones. One report on the EAS pointed out that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has requested the authority to tighten program standards, but Congress "has not granted the DOT any discretion to terminate or reduce service below statutory minimums."

It also helps to remember where EAS came from. Before deregulation, the federal government required airlines to fly in more than 200 small communities to further commerce, postal service and national defense, and subsidized them to do so, according to a 1977 GAO report arguing for an overhaul of this system. Subsidy figures in the report suggest that, in inflation-adjusted dollars, these communities were receiving more in federal subsidies than the EAS is distributing today.

EAS is also a very visible political issue, and congressional members tend to protect subsidies that flow into their districts. According to Mike Boyd, an aviation consultant with the Boyd Group Inc. in Evergreen, Colo., "Many in Congress see the EAS/DOT bill as an afterthought—keeping the votes back home."

While Congress and the FAA may not want to rock the EAS boat, other factors may force some changes. EAS subsidies are determined by a complicated set of factors, from the demand for travel to certain characteristics of the aircraft, supply of seats along the route and competition. Despite the subsidy, it's more lucrative for an airline to fly a 50-seat regional jet than a 19-seat turboprop, the current equipment of choice for over 70 percent of EAS flights. Aviation consultant Boyd said that most airlines need at least 30 seats to fly profitably, and some of the larger airlines have backed away from EAS for that reason, and because the turboprops are aging and will slowly be taken out of service.

A case in point: EAS service in Escanaba might change as Midwest Connect wants to stop flying the small turboprops and focus on regional jet service, and Escanaba doesn't fit into that plan. However, Mesaba is considering an EAS application so Escanaba might still retain that service.

EAS is typically not a boon for airlines either. EAS flights are generally a small part of an airline's scheduled flights. Even Great Lakes Airlines, with 25 percent of the total EAS market, would likely drop out of the program if it could fly profitably without it, according to Gary Ness, director of the North Dakota Aeronautics Commission. For example, Ness said, if Great Lakes could solidify the market in Dickinson, where it has three daily flights, it would likely walk away from the EAS program.

Down another runway

How the program ultimately changes, if at all, may depend on a pending EAS reauthorization bill waiting for a final U.S. Senate vote. It calls for spending $110 million on EAS in 2008. The Bush administration wants to fund EAS at $60 million, which could cut service to nearly one-third of EAS communities.

Boyd said regardless of how the current funding cycle plays, something has to change with the current system. "You can't resuscitate what you've got because it's too far gone," Boyd said, adding that the FAA needs to determine which communities truly require subsidized air service and spend the money needed to connect a community with the rest of the world in the most efficient way. "The feds need to do some triage ... and tell communities, 'We can't provide (everyone with) air service; you need to drive to the nearest airport community.'"