Not content to kick back in his twilight years, Claude Smith operates a 200-unit self-storage warehouse in Rapid City, S.D. For the most part, his business has been strong and steady over the years. “If you’re semiretired, this is a great business to get into to keep you busy and have an improved income,” he said. Smith’s only problem is increased competition; in the past few years, he’s watched numerous storage facilities spring up around him.

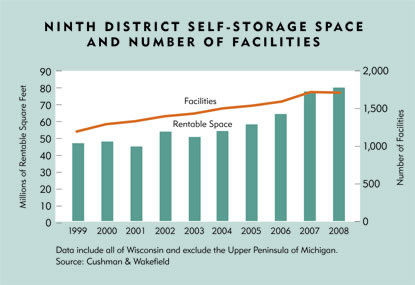

The amount of rentable self-storage space in Minnesota, Montana, the Dakotas and Wisconsin has increased 76 percent over the past 10 years, with most of that increase occurring over the past five years (see charts). Nationally, the volume of storage space nearly doubled over the same period.

This rapid growth has generated healthy profits for self-storage operators, said Chris Sonne, who follows the industry for Cushman & Wakefield, a commercial real estate firm in Irvine, Calif. For evidence, he points to the performance of publicly traded real estate investment trusts, or REITs. “You look at self-storage REITs and the dividends that they offer in comparison to the other commercial REITs, and [they’re] significantly higher,” Sonne said.

The amount of new storage space coming onto the market slowed markedly in the district and nationally this year. Obtaining financing for new construction has become challenging lately, partly because of a perception that the industry suffers from a space glut.

However, in the long run the industry is likely to continue to grow—just like the hoard of personal treasures locked away in “second garages” all over the district.

Bursting at the seams

Self-storage has long been the fastest growing sector of commercial real estate. Six percent of American households rented self-storage space in 1995, according to the Self Storage Association, the trade organization for the industry. Last year, 10 percent of U.S. households rented such space.

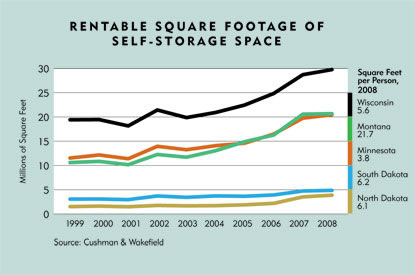

Growth within the district has also been strong. In 1999, there were 1,212 self-storage facilities in the five-state area. Today, there are about 1,700 locations, an annual growth rate of about 4 percent. And square footage in those states has been growing even faster—just over 6 percent annually—indicating that storage facilities are getting bigger as well as more numerous. The district now boasts almost 6 square feet of storage space for every resident, a 55 percent jump in per capita space over the past decade.

The business generates solid cash flow and overhead is relatively low, making it attractive to operators and investors. “It’s like the bank robber who said he robbed banks because that’s where the money is,” Sonne said. Rents typically start at less than $1 per square foot of storage monthly, but vary depending on local land values and demand.

It’s an overwhelmingly mom-and-pop industry. Most self-storage operations are small, comprising one or two facilities. The five largest companies in the industry collectively manage less than 9 percent of all facilities nationwide. The rest are run by individual entrepreneurs like Smith, who opened his warehouse 15 years ago.

Comprehensive data are lacking on utilization of self-storage space—how much capacity in the district is rented, as opposed to sitting empty. But Cushman & Wakefield has developed an econometric model that estimates potential demand for space, based mainly on a market’s population, percentage of households that rent, and average income and household size. The model suggests that despite all the growth in storage space, most markets still have room for expansion.

Rough estimates by Cushman & Wakefield peg current demand in each district state at between 6.5 and 7 square feet per person. By this standard, most of the region has an insufficient supply of storage space.

Based on the firm’s model, the Twin Cities metro appears to be one of the country’s largest untapped markets for self-storage, capable of absorbing an additional 6.2 million square feet—the equivalent of more than 100 football fields. Historically, storage space has been developed in the suburbs of Midwestern cities, where land is cheap. Today, Sonne sees pent-up demand for storage in high-density neighborhoods in the Twin Cities core.

In contrast, Montana has a surfeit of storage space, according to Cushman & Wakefield—21.7 square feet per person. The state’s low population means that the addition of even a small amount of space significantly increases the state’s per capita storage figure.

But generalizations about self-storage supply and demand at the state level can be misleading, because the industry is intensely local. For ease of retrieval, people want to store their excess possessions close to where they live. The typical self-storage facility draws customers from within a three-mile radius. That customer territory might extend for 10 miles in the suburbs and 15 miles in rural areas.

That means that some areas of a state or a metro area could be thirsty for storage space while others are awash in it. This makes deciding where to open new storage space tricky, but Sonne said that developers are getting better at assessing their competition in a particular neighborhood or town and at figuring out facility size and pricing with the aid of planning software.

Locking down, taking stock

The rapid growth of self-storage doesn’t mean it hasn’t been touched by recent woes affecting other sectors of commercial real estate. Growth, while still positive, has slowed in every district state in the past 12 months, according to Cushman & Wakefield. The square footage of self-storage in the five-state region increased 3 percent in the past year, down from an annual growth rate of 6 percent over the past nine years.

Nationally, the amount of self-storage space increased 8 percent in the past year. That roughly matches the annual growth rate in the industry over the past nine years—but is less than half the rate in the previous year and other boom years.

The slowdown runs counter to several reports that have focused on economic troubles as a driver of growth in the self-storage business. There’s scant statistical evidence for the idea that the nationwide housing slump and weak labor market are increasing demand for storage space as more people become renters or relocate in search of work.

Nor is there solid evidence for the countervailing view that industry growth has cooled because of flagging demand for space. That might be the case in some markets, but not in Mandan, N.D., where Sandy Vogel manages two self-storage facilities. Vogel was worried that economic hardship would lead to a decline in business, but local demand for storage is the strongest she’s seen in 20 years. “Over the last two years, there has definitely been an increased volume,” she said.

However, there are indications that self-storage growth has slowed because of difficulties obtaining financing. In recent investor surveys, financing concerns loom large for developers of self-storage facilities.

Some developers of new storage space in the district have been stymied by a clampdown on commercial credit—a problem for all types of businesses in the deteriorating credit environment of the past two years. Today, lenders spooked by the mortgage crisis are requiring self-storage developers to jump through more hoops. Sonne sees a drop in sales of existing facilities as a symptom of tight credit: “There’s a lot of concern in the market about how the housing crisis and the availability of credit will impact [the industry],” he said.

Many lenders are also worried that too much space has been built already, softening demand and rental rates for new facilities. While supply roughly matches or falls short of demand in many areas, a few large markets—Cushman & Wakefield cites Dallas and San Francisco as examples—are overbuilt. This has created the perception of a nationwide storage glut, which has influenced the thinking of district lenders. Even when a developer can demonstrate strong local demand, lenders may be reluctant to finance a new facility until the national outlook becomes clearer.

Space—the final frontier?

National and district growth in self-storage may have slowed in response to restricted access to capital and jitters about a surplus of space in major markets. But if the past is any guide, the self-storage industry should continue to grow. People will always need a place to keep their stuff, and if it can’t fit in their basement or garage, they’ll seek somewhere else to stash it.

Operators of storage facilities report that their customers have become more diverse over the years. “When we first started, it used to be for people living in apartments,” Vogel said. “We’ve found that it’s getting to be more single-family homes that are renting storage.” As more suburban families, retirees and other types of households rent storage space to accommodate the overflow from attics and basements, more will need to be built.

Sonne is optimistic about the long-term outlook for the business. Commenting on the recent slowdown, he said that a little caution isn’t necessarily a bad thing after a period of torrid, undisciplined growth. “Now experience in development really becomes critical, and I think that’s good for the business over the long run,” he said.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.