Tod Maleckar is a “land man” working in western North Dakota’s oil country. He and his staff at Diamond Resources Inc. in Williston pore over deeds and maps at county courthouses to figure out who owns land that may hold millions of barrels of crude oil. Then they track down those landowners and try to sign them to oil drilling leases—before a land man working for another oil company does.

Demand for Maleckar’s services is a leading indicator of the health of the oil industry in the Williston Basin, a vast area in the western Dakotas and eastern Montana endowed with rich petroleum deposits. Oil companies active in the region must secure drilling rights before they sink new wells. When they stop calling, it’s a sign of flagging interest in developing oil fields. In recent months the signs have been discouraging; Maleckar has been getting a lot fewer calls than he did last summer, at the height of the oil boom in North Dakota.

A sharp drop in drilling activity in the region caused by a collapse in oil prices forced him to cut 40 percent of his workforce last winter. And despite an increase in the price of oil since then, business had not picked up appreciably as of late June. “I haven’t had to make any further cuts, but I think I’m going to be very cautious through the end of the year, to see how things go,” Maleckar said.

People in the Williston Basin are at once fearful and hopeful about the oil industry, cheered by an increase in the price of oil this year and some signs of renewed drilling activity, yet still unsure about what the future holds. “No question, that sense is there,” said Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota Industrial Commission’s Oil and Gas Division, which regulates the industry in the state. “It affects Main Street in western North Dakota; it affects the state tax revenues [and] everything in general. We’re kind of holding our breath, I guess.”

For most of this decade oil had been a sure bet in the region. The Basin has produced oil since the 1950s, but in 2000 new horizontal drilling technology allowed oil companies to tap into the Bakken Formation, a deep layer of oil-bearing shale in the northern part of the Basin. Bakken crude is “light and sweet”—low in sulfur and easy to refine.

For most of this decade oil had been a sure bet in the region. The Basin has produced oil since the 1950s, but in 2000 new horizontal drilling technology allowed oil companies to tap into the Bakken Formation, a deep layer of oil-bearing shale in the northern part of the Basin.

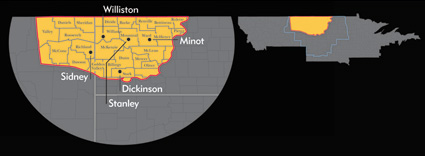

Driven by rising oil prices, the oil rush began in northeastern Montana in 2002, then spread to the western counties of North Dakota in 2006. Drilling rigs sprouted by the score on rolling cropland and pasture, giving way to bobbing pumping units as oil fields were developed. The wells produce natural gas as a byproduct.

Oil and gas development infused wealth into Basin communities such as Williston and Dickinson, N.D., and Sidney, Mont. Oil field service firms thrived and expanded their operations. Farmers and ranchers grew rich on leasing fees and oil royalties paid by the oil companies. A recent study by researchers at North Dakota State University estimated that in 2007 the oil and gas industry spent $3.1 billion in North Dakota, supporting 7,700 jobs and generating $520 million in state and local tax revenue.

Non-oil businesses such as construction firms, retailers, motels and restaurants also benefited from the gush of oil money. The city of Williston handed out over 20,000 “Rockin’ the Bakken” bumper stickers, caps and lapel pins celebrating the boom.

Today prospects for the Basin’s oil economy don’t look as bright. As of early July, with crude oil selling for about half of last summer’s prices, oil companies such as EOG Resources, Marathon Oil and Amerada Hess had drastically cut back drilling in the region. In much of the Bakken, it no longer paid to drill new wells and put them into production.

And when the big oil firms aren’t exploring and drilling, locally based firms that provide them with raw materials, equipment and services suffer as well. Many were forced to curtail operations and lay off workers last fall.

The Ninth District’s oil industry hasn’t gone away. Drilling rigs still dot the countryside in highly productive parts of the Basin such as Mountrail County in North Dakota. Existing wells continue pumping and need to be maintained. Over the summer there was some evidence that oil field activity was increasing in response to higher oil prices.

However, many businesses in the region, oil and non-oil firms alike, want to see a sustained rally in oil prices before hiring new employees or investing in improvements. Oil firms, chastened by the tumble oil prices took last fall, are proceeding cautiously. Non-oil firms have also felt the impact of volatile oil; their anxiety is reflected in a slowdown in business and consumer spending, less demand for bank loans and falling rents for apartments.

Long-time residents of the region recall vividly the 1980s, when a drop in oil prices caused widespread business failures, home foreclosures and an exodus from Williston and Sidney. That probably won’t happen again, even if oil drilling stays at lower levels for an extended period. A somewhat softer landing for the oil economy of the Williston Basin is more likely; businesses and local governments in the region learned hard lessons from their years in the wilderness.

Rigs on the run

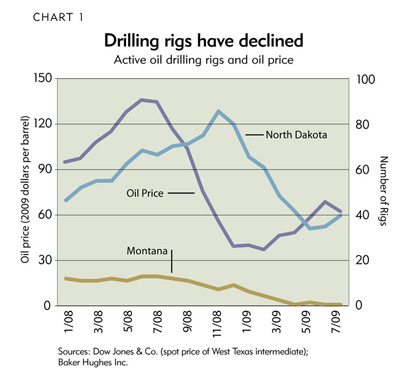

A sharp drop since last fall in the number of rigs drilling new oil wells in the Williston Basin is the most dramatic indication of oil industry retrenchment in the region. “None of us would have ever believed in the summer of last year that it would have fallen this far this fast,” said Maleckar. “It was a shock to all of us.”

Last November, 96 rigs were operating in the Basin, according to Baker Hughes, an oil field technology firm that compiles drilling statistics. All but seven of those rigs were located in North Dakota, the highest number in the state since the early 1980s. By May the number of rigs working the Bakken had fallen to 36. There was one active rig in Montana (see Chart 1).

In mid July the North Dakota rig count bounced back up to 41, perhaps in response to crude prices rising above $70 per barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) in June, a 40 percent increase since March. That was welcome news for Ron Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, an oil and gas trade association. “I think we’ve likely hit the bottom as far as our decline in activity,” he said. But Ness added that the outlook for oil drilling was still iffy because of a lack of capital and fluctuating oil prices.

Diminished cash flow because of lower oil prices has forced oil companies to slash their exploration and drilling budgets. And even for companies with the money to drill, the precipitous fall in oil prices (in July 2008 crude peaked at nearly $150 a barrel) has made drilling for oil financially untenable in much of the Williston Basin.

The economics of tapping the Bakken Formation get shaky when oil dips below about $75 a barrel. Compared with other oil regions such as west Texas and the Gulf Coast, drilling in the Bakken is expensive. To reach oil, crews must bore 10,000 feet down, then horizontally through a shallow layer of shale. “Fracing”—injecting a mixture of water and sand that fractures the shale—helps coax the honey-hued crude to the surface. Last year drilling and completing a typical Bakken well cost about $6 million.

Development costs have fallen since last summer because of lower demand for materials and labor. But a well still must produce a lot of oil over its expected working life of 25 to 30 years to cover its expenses, which include taxes and royalties paid to landowners. It’s even tougher for oil companies operating in the Williston Basin to turn a profit because of limited pipeline capacity. In both North Dakota and Montana, oil must be transported by rail or truck to refineries, increasing production costs. As a result, in the past 18 months, Bakken oil has been discounted anywhere from 7 percent to 60 percent below prices for West Texas crude, depending on production volume and transportation costs.

Unable to recoup their expenses, oil firms have opted to let their oil leases expire and forgo drilling in many parts of the Basin. Since last fall the majority of drilling activity has focused on Mountrail, eastern McKenzie and northern Dunn counties in North Dakota, areas where wells can produce three to five times as much oil as wells elsewhere in the region.

In the heart of the Bakken, new wells in choice areas can still be expected to pay their way even when west Texas (undiscounted) oil prices dip below $60 per barrel—which is why Stanley, the seat of Mountrail County, is still riding the oil boom. Since 2006, when Texas-based EOG scored a big oil strike in the county, the town of 1,400 has become a base for oil companies and oil field service firms that want to be close to the action.

“It’s really taken off, and it’s still going gangbusters here,” said Mayor Mike Hynek. EOG is building its North Dakota office and a rail shipping facility in Stanley that together will employ 65 people. A local real estate agent said that residential property values have risen 10 percent to 15 percent over the past five years with no sign of letup because of demand for housing from oil industry workers and their families.

In the rest of the Bakken, many people in the industry say it will take NYMEX oil prices consistently north of $70 a barrel to cover production costs and significantly increase drilling. An early-summer hike in oil prices was insufficient to instill confidence in oil companies and their investors, said Steven Durrett, CEO of Augustus Energy Partners, an oil and gas developer based in Billings, Mont. “Continued volatility in the crude markets makes companies hesitant to loosen up their wallets,” he said via e-mail. Realizing a return on a new well can take up to two years, Durrett said, so oil firms and private equity investors crave stability—oil prices above a critical threshold that appear to have staying power.

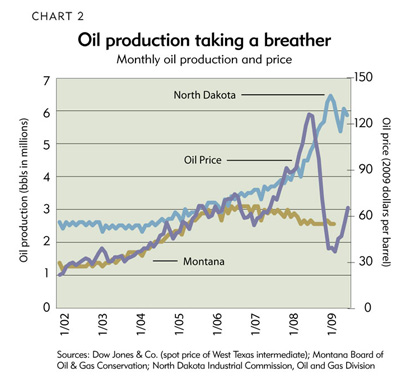

Lower, variable oil prices have also led oil firms in the Basin to throttle back output from existing wells, contributing to a marked drop in oil production since last fall (see Chart 2). North Dakota production peaked in November at about 6.5 million barrels; by April it had fallen about 10 percent.

Contraction pains

The decline in drilling has resulted in reduced sales not just for drilling contractors—many of whom are based in other states—but also for a multitude of local service firms that provide the oil companies everything from leasing services to fracing sand to well parts. The Petroleum Council estimates that every new drilling rig supports 40 jobs in the oil industry.

Oil activity always picks up in the spring when load restrictions are lifted on county roads, allowing crews to resume heavy drilling and maintenance work. Oil field job listings with Job Service North Dakota have increased since the end of March, when oil-related companies posted only 45 job orders statewide. At the end of June, there were 65 listings. But demand for oil field labor was still nowhere near the level of June 2008, when Job Service had over 100 listings in that category.

Many oil field service firms in the Basin were still feeling contraction pains; to survive they laid off employees and cut costs. Maleckar of Diamond Resources said his firm was getting very little new work from oil firms. He’s meeting his reduced payroll by renegotiating old leases due to expire in the next few months.

Another Williston company, Red River Supply, was trucking less drilling salt and saltwater (injected underground to reduce pressure on drill bits) to well sites than last year. Owner Rich Vestal said that by April he had laid off almost a third of his workforce; he figures many of those workers left town to look for employment.

At Richland Pump & Supply in Sidney, owner David Williams has had to cut one of his 12 employees. After several years of strong growth, orders have fallen off for oil well components. He expects sales to decline 20 percent this year, despite the June spike in oil prices that raised spirits across the Basin.

“I’m hoping there’s a change, but when the price comes up things don’t automatically get busier,” he said. “The price has to stay there for quite a while before the oil companies are going to start doing anything.” Williams was hoping to cut costs and avoid further layoffs by reducing his inventory and waiting to rebuild stocks until business improves.

The struggles of these firms and hundreds of others in the Basin ripple out far beyond the oil patch. Stagnant oil field revenues mean fewer goods and services purchased from other businesses that have become accustomed to black gold in their cash registers. Local government also feels the impact when less direct and indirect oil spending reduces tax revenue.

Star not so bright

A drive down Second Avenue West, the main commercial strip in Williston, reveals no hints of faltering prosperity. At the end of the day, pickup trucks laden with oil field tools and equipment line up outside motels. Help wanted signs hang in the windows of restaurants, bars and gas stations. On the west side of town, clusters of upscale single-family homes and townhouses are under construction, some adjacent to trailer parks and modest one-story houses built during the 1970s boom.

Although “The Western Star” is the hub of the region’s petroleum industry, with 200-odd oil field service firms, the city of 14,500 does not live by oil alone. Before oil was discovered in North Dakota in 1951, farming was the Basin’s economic mainstay, and it remains so. As oil prices fell last fall, small-grain farmers reaped handsome profits because of high commodity prices. A plant that processes peas, lentils and chickpeas was acquired by a Canadian firm and expanded in 2007.

But the oil industry’s recent travails have cooled a regional economy that last year burned red hot, untouched by the recession that was tightening its grip on the nation as a whole. “We’re not feeling the pressure that we hear is going on around the rest of the country, but [the oil downturn] has had an impact,” said Ward Koeser, president of the city commission and owner of a local communications firm.

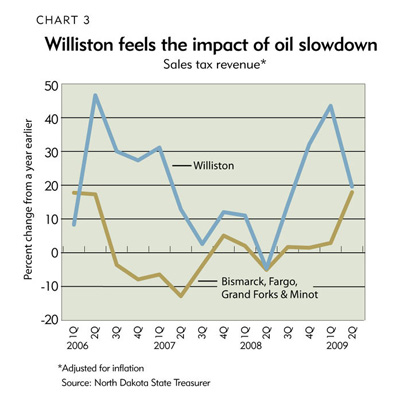

Williston is still doing very well compared with other communities in the state (see Chart 3). City sales tax collections increased 20 percent in the second quarter over the same quarter in 2008. However, Williston tax collections for April and June fell 2 percent below city estimates, suggesting that economic growth is slowing.

That worries city officials. City sales taxes are earmarked for infrastructure improvements and don’t fund operations. But receipts from a state tax on oil production dropped sharply in the first quarter, and the city auditor forecasts a $6.1 million budget deficit this year unless oil tax funds and revenue from other sources rebound in coming months. “That’s going to be a challenge, something we’ll have to wrestle with,” Koeser said.

Other signs that the city’s fortunes may be on the wane include reduced commercial lending and falling rental rates.

First International Bank & Trust, with offices in Williston, Watford City and Killdeer, is one of the biggest lenders in the Basin. The bank lends to farmers, manufacturers and retailers as well as oil field service firms. Not surprisingly, demand for credit from oil-related businesses has fallen over the past year, said President Larry Dewhirst. During the boom oil field firms borrowed to buy new equipment and upgrade facilities; now that oil drilling and production are down, they’re delaying new capital investments. But lending to non-oil businesses has also dropped as businesses put expansion plans on hold. “There’s not as much demand for commercial loans right now,” Dewhirst said.

A year ago landlords were charging over $1,000 per month for a two-bedroom apartment. Today apartment rates have dropped because there are fewer oil workers in town who can afford high rents. Mike Marcil, a Fargo-based real estate developer, said that his company lowered rates last spring at several properties it owns in the city. “There are still more people who need an apartment in Williston than there are apartments, but what they’re able and willing to pay is declining,” he said.

Marcil and a partner plan to expand an apartment complex in the city, but securing financing has become more difficult over the past year. Many local banks, including First International, were shying away from financing construction of multifamily housing. “If you’re at the end of a boom cycle, you don’t want to be investing in apartments,” Dewhirst said.

Despite the vicissitudes of the oil industry, some Williston businesses are expanding their operations. Even as crude prices were dropping a year ago, Sheila and Bryan Goehring undertook an extensive remodeling project to house their video rental business and a new liquor store. The couple took out a $450,000 loan from the U.S. Small Business Administration to pay for the work. “We knew that even if they quit drilling and oil production in the area dropped off considerably, it would still be something we’d want to go ahead with,” Sheila Goehring said.

Bryan Goehring figures liquor and video rentals are oil-bust resistant (“knock on wood”). He said business improved at a bowling alley the couple owns when drilling declined last fall; laid-off oil field workers had more time to bowl.

But other Main Street businesses have settled into wait-and-see mode. At Ryan Motors, a Chrysler and Honda dealership, sales in June were down about 30 percent from last summer, when truck purchases by oil field service companies helped the dealership post its third consecutive year of 10 percent to 15 percent growth. Last fall those firms stopped buying, and despite the spring uptick in oil field activity, oil-related sales had not fully recovered. This summer General Manager Barron Parizek’s goals were modest: Sell enough vehicles to general consumers to avoid laying off employees. “We’re maintaining and seeing what’s going to happen in the future,” he said.

Last of the gravy?

Uncertainty about oil pervades other communities in the Williston Basin. For all of the bustle in Stanley, there were subtle signs that the local economy had cooled somewhat since last summer. A new apartment building with rents geared to oil salaries had vacancies, and fewer oil field workers were stopping in for breakfast at Joyce’s Café on Main Street. Owner Cory Rice said his oil field clientele had dropped 75 percent since last fall.

Over the Montana border in Richland County, which accounts for over half of oil production in the state, vanishing oil rigs represent another stage of an industry slowdown that began two years ago. Oil production in the county peaked in August 2006 and by the end of last year had fallen by more than a quarter. In this part of the Bakken, the output of new wells hasn’t been enough to replace the naturally declining production of older wells. “The activity in Montana is declining,” said Durrett of Augustus Energy Partners. “The good areas have largely been drilled.”

In the county seat of Sidney, residential valuations started softening in late 2007 after several years of strong growth, said Leif Anderson, owner of Beagle Properties, a local real estate agency. As oil field exploration and drilling leveled off, so did the number of oil company managers buying $200,000-plus houses.

Today Anderson is worried about eroding demand for less expensive houses if city residents who have been laid off from oil field service firms in the area don’t go back to work. “If the price of oil doesn’t come up significantly, I feel that the boom time, the gravy, may be over,” he said.

There’s evidence that the recent virtual shutdown in drilling is further undermining the area’s economy. Local banks report a drop in demand for credit from oil service companies since last summer; one banker observed that firms have all the equipment they need to perform maintenance work on existing wells.

The Sidney Job Service Workforce Center has seen a marked drop in listings for non-oil jobs. In June 2008 about 180 employers had job openings in Richland County; a year later there were fewer than 80 (although there were plenty of openings in retail and food service—Kentucky Fried Chicken in Sidney was closed some weekdays because of problems finding help).

And the drilling pullback has hurt the bottom line of Tri-County Implement, a farm equipment dealer in Sidney that services oil field equipment as a sideline. Since last winter fewer oil field trucks have come into the shop for repair, said co-owner Tami Christensen. She expected the decline in oil field repair work, combined with farmers’ chagrin over smaller oil royalty checks, to translate into a 5 percent decline in sales this year. “Like everybody else, we’re going to watch what we’re doing a little closer, and we probably won’t be doing any big expansions this year,” she said.

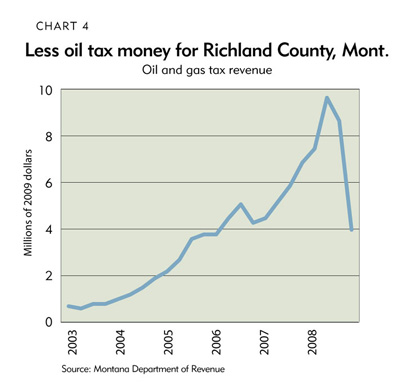

As in Williston, local government officials were concerned about a drop in tax revenues tied to oil production. Since 2002 Richland County has spent tens of millions of dollars in oil tax revenues on public infrastructure such as a new criminal justice center and renovation of a county park. “We’ve done it all just on oil money; we haven’t gone to the taxpayers for anything,” said County Commissioner Mark Rehbein. That may have to change in the future; in the fourth quarter of last year, the county received $4 million in oil tax receipts—less than half the amount it got in the previous quarter, when oil prices peaked (see Chart 4).

Watching and waiting

Folks in the Williston Basin talk about the price of oil like people elsewhere talk about the weather. Is it up or down today? What’s the outlook for next week, next month and next year? Many express hope that the downturn in drilling is a brief hiatus in a long period of prosperity in the region. If oil prices mount a sustained rally later this year in response to global economic recovery, drilling could come back strong, at least in the core areas of the Bakken that promise oil companies the greatest return on their investment.

Folks in the Williston Basin talk about the price of oil like people elsewhere talk about the weather. Is it up or down today? What’s the outlook for next week, next month and next year?

To that end, in April the North Dakota Legislature enacted a tax incentive for newly drilled wells. When oil drops below $70 a barrel, oil producers pay a top tax rate of 7 percent on oil from those wells—3.5 cents less than the standard rate. The tax break expires after 18 months or when the well exceeds production thresholds.

Helms of the North Dakota Industrial Commission anticipates a spurt in drilling early next year, when Enbridge Inc. of Canada plans to complete a pipeline expansion that will allow an extra 50,000 barrels per day of crude to flow east to Minnesota. Easing constraints on oil shipments may eliminate or reduce the market discounts on Williston Basin oil.

But if oil activity stays depressed for years, the consequences might not prove as damaging to the economic well-being of the region as the oil crash of the mid-1980s. When oil prices plummeted then, 5,000 people without a livelihood pulled up stakes and left Williston. Home foreclosures rose as property values fell.

Certainly a long-term contraction in oil drilling—and over time, significant drops in production from existing, aging wells—would mean hardship for the multitude of oil field service firms in the Basin. Some companies would fold—the fate of a number of oil field firms in the 1980s; those that survived would have to get back up to speed quickly when oil activity picked up again.

Maleckar of Diamond Resources frets that the land men he has laid off will find work in oil fields elsewhere in the country and not return when oil activity recovers. “For all of us, we wish it was not such an up-and-down deal,” he said. “When you lose people, it’s not like you can go and grab them off the shelf.”

But much has changed in the Basin over the past 25 years. For one thing, farming—for more than a century the backbone of the economy—is more stable than it was back in the late 1980s, when a drought compounded the misery of low crop prices. So far in this recession, prices for wheat, canola, peas and other commodities have held up fairly well.

For another, some Basin communities have diversified their economies since the 1980s oil bust. More than a dozen oil-related companies have a presence in Dickinson. But the city of 16,000 also hosts a state university and tourists headed for nearby Theodore Roosevelt National Park. And it’s home base for a number of non-oil companies, including cabinetmaker TMI Systems and Steffes Corp., a manufacturer of refrigeration and air conditioning equipment.

Those firms have received low-interest loans and other forms of aid from local government—part of a concerted effort to broaden the local economy beyond oil and agriculture. Said Gaylon Baker, executive vice president of Stark Development Corp., a nonprofit economic development group: “A number of community leaders saw [the oil crash], and they said, ‘We don’t want that to happen to us again.’”

That sentiment is shared by cities such as Williston that remain more dependent on oil. Businesses, investors and local governments behaved differently in the recent boom than they did in the 1970s oil rush. They exposed themselves to less risk, remembering the trauma they—or someone they knew—experienced the last time oil prices tanked.

Lessons from the bust

For the most part non-oil businesses in the Williston Basin avoided taking on a lot of debt to expand, even as oil prices and drilling activity soared. Anderson’s reaction to the boom at Beagle Properties in Sidney was typical: “I probably could have expanded this office and added more agents, but because I was around for the last boom, I didn’t borrow a bunch of money and do that. I definitely had the mindset that this boom won’t last forever.”

A few businesses in the Sidney area borrowed heavily to capitalize on the boom, and “in most cases those guys have gotten in trouble,” Anderson said.

Even oil field service firms that had the most to gain from the oil rush played it cagey. Borsheim Crane Service in Williston, a provider of heavy cranes and trucks used in well construction, borrowed over $1 million for new equipment in 2007 and 2008. But owner Tyler Goodman he says he was careful not to go overboard. The memories of the 1990s, when he had to scrounge for every conceivable type of work to keep the firm afloat, were still fresh. “We were pretty conservative in our borrowing, compared with the opportunity,” he said.

Banks also lent conservatively, particularly for housing projects. Local banks and other North Dakota financial institutions that were saddled with hundreds of home foreclosures in the late 1980s took pains to protect themselves when demand for housing rose again with an influx of oil workers. Less housing was needed in this boom because drilling workers often lived at the well site in temporary housing or “skid shacks,” but banks also made housing projects more difficult to finance by requiring developers to put up more equity.

Typically, banks require developers in western North Dakota to bring more of their own capital to the table to qualify for a loan—25 percent to 40 percent of the project cost, compared with 20 percent in Fargo and other cities in the state. The reason is cyclical demand for housing in an oil economy, said Dewhirst of First International; volatility increases financial risk.

Bitter experience has also guided the actions of local officials in the Basin. During the boom cities and counties invested in new infrastructure and services—Richland County built its justice center, the city of Williston spent $25 million to upgrade its water system and Stanley hired two police officers, tripling its police budget.

But despite high demand for housing, they resisted the temptation to subsidize new residential development. In the early 1980s the city of Williston footed the bill for street improvements in planned subdivisions, to encourage development. But many of the subdivisions were never built, saddling the city with vacant lots and $27 million in bond debt. Determined not to repeat its mistake, this time the city required developers to pay for their own lot improvements. Other communities such as Sidney and Stanley have followed Williston’s example, letting developers and banks bear all the market risk.

Koeser sees the drop in oil prices and drilling activity since last fall as a vindication of the city’s measured approach to the boom. “I don’t feel that we’ve overreacted this time,” he said. “We realize that oil is cyclical—it goes up and it goes down. When there are as many of us around who have lived through it, we’re going to be a little cautious about what we do.”

Much of the private sector in the Williston Basin adopted the same attitude toward the run-up in oil prices and drilling activity of the past few years. The good times rock in the Bakken, as the bumper stickers say. Just be ready for when the music stops.

Research Assistant Wonho Chung contributed data collection and analysis to this article.