Financial literacy is important. This statement, while never controversial, is being taken more seriously now, in the midst of a financial crisis, than it ever was in the past. While it is unclear exactly what factors and in what combination caused the economic meltdown, it is likely that a lack of personal financial literacy on the part of consumers played some role.

As the economy starts showing signs of recovery, financial education practitioners are looking to seize the moment by focusing more resources and public attention on financial education. For these practitioners, research that offers insights for sizing up the problem and devising effective financial education programs is a valuable tool.

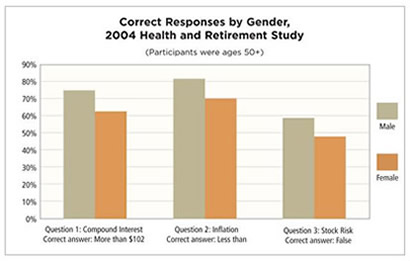

Recent research completed by Dr. Annamaria Lusardi, the Joel Z. and Susan Hyatt Professor of Economics at Dartmouth College, and her coauthors offers a host of information on the extent to which individual consumers lack the knowledge necessary to make prudent financial decisions. In particular, Dr. Lusardi's research has found that while low levels of financial literacy are a widespread problem for both genders, women tend to be less financially knowledgeable, on average, than men.

Community Dividend spoke with Dr. Lusardi to learn more about the gender gap in financial literacy and discuss how financial education practitioners can use her research to reach women more effectively.

Community Dividend: Let's start with the general findings of your research. Broadly speaking, what have you found out about the current state of financial literacy?

Annamaria Lusardi: What my coauthors and I have found by examining data from modules on financial literacy we've designed for national surveys in the U.S. and abroad is that there is a very low level of financial knowledge among the population, especially among women. However, one point I'd like to make is that we have not become more ignorant than before. What's happened is that the world around us has changed, but our knowledge is lagging behind. We're transitioning to a world of enhanced personal financial responsibility, where the pension landscape is shifting from defined benefit plans to defined contribution plans, where we have to make decisions about saving for our children's education, where we confront complex financial instruments, and so on. This is happening especially quickly in the U.S., where the formal and informal safety nets are not as wide as they are in many other developed countries.

CD: Could you provide some context for the gender gap you've observed in your research? Specifically, are men more knowledgeable about financial matters than women, but still not knowledgeable enough, or would achieving parity mean that women would have adequate levels of financial literacy?

AL: We've found that both men and women have too low a level of financial knowledge to be well-equipped to make decisions in our current, complex financial markets. For example, in a survey designed to assess debt literacy, or financial knowledge related to debt, we found that only a third of all respondents knew that they can't eliminate credit card debt by paying a minimum amount equivalent to the interest payment. [For more on the surveying Dr. Lusardi and her colleagues conducted, see the sidebar below.]

In that instance and others, when we break the data into gender groups, we find that women fare worse than men. While it's troubling that there's a gap, it's especially worrisome that women are sitting at the bottom of the scale at a time when they often have to fend for themselves in a financial world that is increasingly complex. The divorce rate is much higher than in the past, single motherhood is very high in certain demographic groups, and the greater longevity of women calls for more retirement savings for women than for men. On top of that, women are often concerned about saving for their children's education and helping their aging parents.

CD: Has your research shown that there are particular subgroups of women that fare better or worse than others?

AL: Our samples aren't so big that we can cut the data in such a granular way. What I can say is that when we cut the data not within gender, but by larger groups like age, race, level of education, and socioeconomic status, we find lower levels of financial literacy among the young and the old, racial minorities, individuals with low levels of education, and individuals with low incomes.

What this means is that if you're a woman and you're young, or if you're a woman and you're African American or Hispanic and maybe also low-income, you're more likely to display very low levels of financial knowledge. Women in the subgroups I mentioned are already vulnerable for a variety of reasons, and these low levels of financial literacy put them in an even tougher position.

CD: Your research looks at financial literacy levels around the world. Have you observed a similar financial literacy gap between men and women in other countries?

AL: Yes, and I think that looking at the cross-countries comparison is very informative and important. In almost every country that we've looked at, including Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Ireland, we've found a gender difference. So, irrespective of the education system of the country, the retirement system, or the labor force participation rate, the gender effect persists.

I'm just back from New Zealand, where yet again—in a survey very similar to the ones we have done here in the U.S.—a gap in financial literacy between men and women has been found. The fact that a gender difference is such a robust feature of the research and that it persists across countries indicates to me that there's something there, and that the topic of women and financial literacy deserves more thought and attention.

CD: What are the implications of the low levels of financial knowledge among women? In your opinion, do they hold women back?

AL: I do think they're holding women back. One of the questions in our research is, "Does financial literacy matter?" Our empirical work shows that financial knowledge does, in fact, affect behavior. People with higher levels of financial knowledge are less likely to borrow at high costs and more likely to participate in financial markets, accumulate wealth, and plan for retirement. Knowledge does translate into behavior that is associated with potentially higher financial well-being.

CD: In your experience interacting with policymakers and financial education practitioners, have you found that there's broad awareness of the gender gap in financial literacy?

AL: I'm not sure that the groups you mentioned are fully aware of the gender gap, and when I look at programs that have been implemented, I don't see particular attention paid to gender. Certainly, there are institutions with gender-specific missions that are pushing this idea, but on the whole, I feel one of the problems with existing financial education programs is that they're too one-size-fits-all. In order to be effective with financial education programs, we need to think a lot more about the audiences those programs are targeting. In particular, we need to think more about targeting and reaching women.

I've mentioned that my research shows women have low levels of financial knowledge, but what I've also found is that when we ask women to assess their own financial knowledge, they're aware that it's low. While other groups think they know more about personal finance than they actually do, women tend to acknowledge what they don't know. This is very important, because it indicates women are sensitive to their lack of knowledge and are therefore potentially more interested in addressing it.

Our experience at Dartmouth has shown this to be the case. When we did focus groups to devise a program to help Dartmouth employees save for retirement, I was struck by how articulate women were in describing their needs and objectives. What we also found is that women were looking forward to getting advice and help.

In all of the financial programs and initiatives I've been involved with, I've seen that women are an eager-to-learn audience and are expressing a demand for being better informed and more knowledgeable. If you go to a financial education program, you'll likely see that a large majority of the audience is women. If you look at the market for financial advice, the more successful books and writers are those that target women.

CD: During your research, what have you learned about how practitioners can tailor their programs to have a greater effect on women?

AL: What I've learned is that the first step in making a program effective is to listen. One has to listen to the concerns and problems of the group one is trying to address. To really improve financial knowledge, you need to go and talk to people and design programs with the participants you are trying to affect in mind.

One organization that has used this approach effectively is Doorways to Dreams. I heard about their initiatives from the founder and president, Peter Tufano, when I visited Harvard Business School last year. The objective of one of their projects was to improve the financial knowledge of mostly young, low-income women. They knew that using a classroom approach with this audience was probably not going to work. What they discovered from talking with and learning about this audience is that they play video games. In response, they designed a video game that puts the player in the role of managing a celebrity figure's finances. The game teaches players the workings of credit cards, annual percentage rates, and so on. It was an effective initiative because it gave women—most of them low-income—what they wanted. Financial literacy should start from the needs and wants of the target audience, not from our view of what people need to know. [To play the video game Dr. Lusardi describes, visit www.celebritycalamity.com.]

CD: Looking ahead, what do you think the future holds for financial education?

AL: I started working on these issues many years ago, when financial education was mostly considered a sideshow. The current financial crisis has made clear how dire the consequences of financial mistakes are and has highlighted the need for increased financial education. I believe the present circumstances have great potential as a teachable moment. More than ever before, we've become aware of how important it is to know the ABCs of finance.

My hope is that the current momentum doesn't go away—that the moment doesn't pass us by, but instead is viewed as an opportunity to get serious about implementing financial education programs. I'm optimistic that more attention will be paid to financial education. In most countries in the world—from developed countries and, more and more, to developing ones—there are people and institutions thinking hard about how to improve financial literacy and how to be effective in providing financial education. One question for practitioners and policymakers in the U.S. is whether they want to be leaders in this field or lag behind.

To learn more about Dr. Lusardi's work, including her recent book Overcoming the Saving Slump: How to Increase the Effectiveness of Financial Education and Saving Programs, visit www.dartmouth.edu/~alusardi and http://annalusardi.blogspot.com.

Determining how much people know about personal finance

To uncover how much individuals know about personal finance, Dr. Annamaria Lusardi and her coauthors have inserted finance-related questions into a variety of existing surveys, both in the U.S. and abroad. For example, Dr. Lusardi and her collaborator Dr. Olivia Mitchell created the following three-question module that was inserted into the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The HRS surveys a sample of Americans over the age of 50 every two years and is supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration. The three personal finance questions are designed to cover the basic concepts of compound interest, inflation, and stock risk. A graph indicating correct responses by gender appears below. Question 1: Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2 percent per year. After five years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow: more than $102, exactly $102, or less than $102? Question 2: Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1 percent per year and inflation was 2 percent per year. After one year, would you be able to buy more than, exactly the same as, or less than today with the money in this account? Question 3: Do you think the following statement is true or false? Buying a single company stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund. Click on chart to view larger image. |

Defining our termsFinancial literacy: The ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively for a lifetime of financial well-being. Financial education: The process by which people improve their understanding of financial products, services and concepts, so they are empowered to make informed choices, avoid pitfalls, know where to go for help, and take other actions to improve their present and long-term financial well-being. Source: 2008 Annual Report to the President, President's Advisory Council on Financial Literacy, U.S. Department of the Treasury, January 2009. |

Fed site features financial education resourcesThe Federal Reserve System is committed to helping individuals of all ages build their personal financial skills and knowledge. To access the Fed's financial education resources, including consumer guidebooks, teachers' guides, and online learning tools, visit www.federalreserveeducation.org. |