Interview conducted July 15, 2009.

Photography by Peter Tenzer

For four decades, when the world has faced financial crisis, ethical quandary or managerial impasse, it has turned to Paul Volcker.

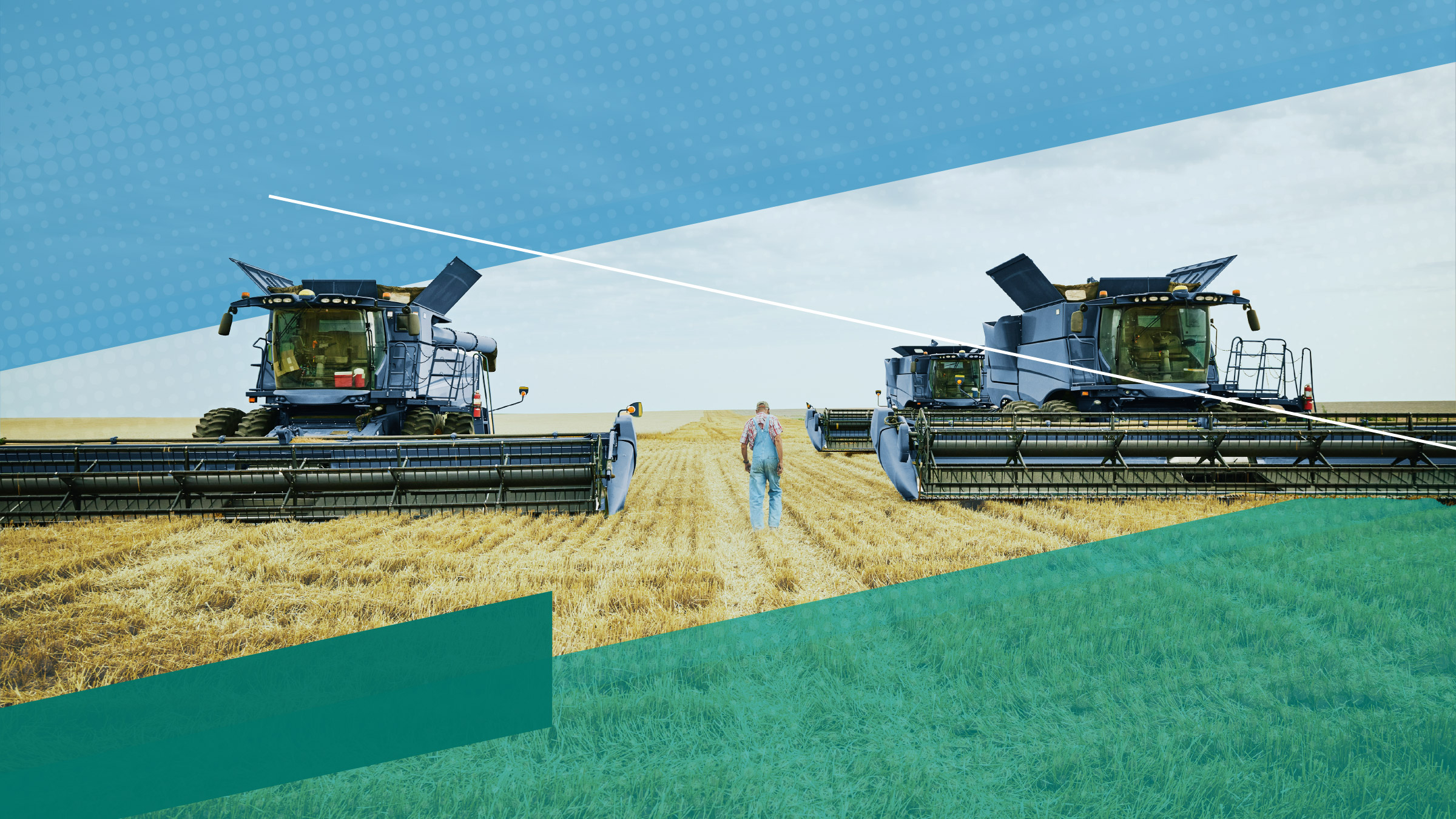

He’s best known, of course, as the Fed chair who—in that clichéd but vivid phrase—“broke the back” of inflation in the early 1980s by restricting growth in the money supply and allowing the fed funds rate to rise as high as 20 percent. He faced enormous criticism for doing so. As the economy slowed and unemployment rose, building contractors shipped 2x4s to his office and farmers protested on tractors in front of the Fed; one powerful congressman demanded his impeachment.

But Volcker was steadfast, and his strategy worked. Inflation dropped from over 13 percent in 1979 to under 2 percent in 1986, and the economy sprang back to health—thereby establishing the Fed’s credibility as a guardian of price stability and economic growth.

Less known is Volcker’s central role while at the U.S. Treasury in the early 1970s in designing the floating currency regime that replaced the Bretton Woods gold standard agreement, or, as Fed chair during the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, in convincing major U.S. banks to restructure their international loans.

After chairing the Fed from 1979 to 1987, Volcker joined the private sector for nine years as chair and later CEO at a small investment banking firm. But his public profile remained prominent.

In 1988 and 2003, he chaired national commissions on public service that recommended major overhauls of federal government organization and personnel practices. From 1996 to 1999, he headed a committee to investigate Swiss bank assets of Nazi persecution victims and from 2000 to 2005 oversaw an effort to develop consistent international accounting standards. In 2004, he directed an independent inquiry into the United Nations Oil for Food Program, and in 2007 he chaired a panel of experts to review the World Bank’s Department of Institutional Integrity. In 2008, he led a Group of Thirty working group in developing an international “framework for financial stability.”

Today, he serves as chair of the President’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board, a commission established by President Obama to provide independent expertise in addressing the nation’s financial crisis.

In mid-July, Volcker sat down in his New York office with then Minneapolis Fed President Gary Stern. The two have been colleagues since Stern worked at the New York Fed during Volcker’s tenure there as president in the mid-to-late 1970s. Just back from an overseas conference, Volcker was recovering from a cold; he sipped hot tea and often preceded his comments with deep, throat-clearing coughs. But being under the weather had no apparent impact on the quality of conversation. In sharing ideas on prospects for regulatory reform, the Fed’s accomplishments and shortfalls, obstacles to better public service and other issues, Volcker was as thoughtful, cogent and resolute as ever.

Regulatory reform

Stern: Why don’t we start with the Treasury department’s regulatory reform proposal before Congress? What’s your assessment of that proposal?

Volcker: I’d guess that about 80 percent of it incorporates what has become the common ground among almost everybody who has looked at this thing. You’ve got to do something about the derivatives and nonstandardized derivatives: an orderly clearing mechanism, some kind of a rapid resolution process for financial institutions of the sort that de facto exist for the banks through the FDIC, some kind of systemic oversight mechanism. There’s a big question as to how that’s to be done, but the Treasury proposal incorporates an oversight mechanism. These are key points.

Some secondary things they dropped for the moment. They haven’t said anything about Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, said they’ll come back to that later. Credit rating agencies just got a once-over lightly. So there’s some unfinished business here, but a number of the important points are incorporated.

I do not share one part of the general philosophy which seemed to emerge from this, particularly the proposal that the Federal Reserve supervise directly all “systemically important” institutions. I don’t know what “systemically important” institutions are, incidentally, but I’m sure that if you picked them out, people will assume they’re going to be saved, that they’re too big to fail. At the same time, there’d be some that you don’t pick out in advance that you’d want to save under particular circumstances.

So I think that is a mistake. What I have argued for in a number of speeches and otherwise is, yes, you need an overall systemic overseer—not with the regulatory or supervisory authority over particular institutions, rather somebody looking over things, beyond individual institutions, for the weaknesses in the system, looking at things that are developing that are problematical, various tendencies, some other toxic assets perhaps in some other form.

What I have argued for in a number of speeches and otherwise is, yes, you need an overall systemic overseer—not with the regulatory or supervisory authority over particular institutions, rather somebody looking over things, beyond individual institutions, for the weaknesses in the system, looking at things that are developing that are problematical.

Somebody ought to be alert to that. And then they can go to the supervisor and say, “We’re concerned about this. You should do something.” Just how much authority you give it, as opposed to moral authority, is I think a question. But that’s a role I see for the Federal Reserve.

Stern: So you think the Fed should be the …

Volcker: The Fed should be the overseer, not the über-supervisor/regulator, if I could make that distinction. Then that leaves the question of who does the actual regulation, and the Treasury basically ducked a large new initiative by not proposing any big changes in the existing situation.

I think ideally you’d probably have a single bank regulator, connect that with the Federal Reserve somehow, but keep it separate from day-to-day Federal Reserve supervision.

Stern: So you might have something like the OCC [Office of the Comptroller of the Currency] as the single bank regulator but with some connection to the Federal Reserve?

Volcker: Yes. I don’t think I’d call it the OCC because that implies a connection to the Treasury, although they are pretty independent. It should be an independent supervising agency. And I could imagine that the chairman of that supervising agency also sits on the Federal Reserve Board as vice chairman for supervision to make sure the Federal Reserve stays in the loop.

And I could imagine—I’m just thinking out loud—that the Federal Reserve Board would be given responsibility for reviewing regulatory proposals by the bank supervising agency so you get some additional eyes on actual banking regulation.

Regulation of nonbanks

Volcker: Then I wouldn’t regulate so strictly the nonbanks. If they get big enough, then they’re going to need capital requirements and leverage requirements. But I don’t think that’s going to be many firms. I’d like to create the impression, to the extent you can, that there’s no automatic bailout of those institutions.

Stern: I have a lot of sympathy for that idea. I’m not sure why people have gotten so concerned about hedge funds and other institutions that really haven’t been particularly involved in the current crisis in any direct way.

Volcker: Well, of course, you have the example of Long-Term Capital Management, which so many thought was a terrible risk. I thought that was an overreaction there. But that was a hedge fund. This crisis in some sense started when Bear Stearns had a couple of hedge funds that ran into trouble, and they supported it. That raised a lot of questions about what was going on. So hedge funds have not been entirely exempt from the current problems.

Stern: No, they haven’t, but they haven’t been …

Volcker: I don’t think they need terribly detailed regulation. Where I run into conflict with the Treasury proposal, or don’t really understand it, is a matter of regulatory philosophy. The image I have is that we should deal with commercial banks as basically service organizations: They are dealing with customers, they’re dealing with clients, they’re providing some very basic services the country needs. And in recognition of the importance of those basic functions, virtually every country provides certain protections and support.

It’s been true from time infinitum. Banks take care of the payments system. They provide outlet for liquid funds, safe outlets. They provide credit to individuals, to households, to businesses, to governments. These are all pretty basic functions. The infrastructure of the system is pretty much run by the banks too. All those things are very basic, and I think there’s no reason they can’t be profitable. In fact, some of the best profits recently in banking have been in those services.

But, and this is partly substantive and partly symbolic, I don’t think a bank should own a hedge fund or own a private equity fund because that puts them in a different business. Those are capital market businesses, a wholesale business, transaction-oriented rather than securities-oriented businesses. I don’t want bank managements to be distracted by the desire to make a lot of money in those businesses. Nor should they be reliant on a lot of proprietary trading.

Think of the situation with Goldman Sachs, which was in the papers this morning [with reports of large profits]. They’ve had government assistance. They were presumably deemed too big to fail. And at the same time, they have an enormous trading book. They’ve made a lot of money. There’s nothing wrong with making money, but I don’t want them to make money by taking those risks with the support of the taxpayer.

I wouldn’t regulate so strictly the nonbanks. If they get big enough, then they’re going to need capital requirements and leverage requirements. But I don’t think that’s going to be many firms. I’d like to create the impression, to the extent you can, that there’s no automatic bailout of those institutions.

Commercial banks [are] … basically service organizations: They’re providing some very basic services the country needs. And in recognition of the importance of those basic functions, virtually every country provides certain protections and support … But, and this is partly substantive and partly symbolic, I don’t think a bank should own a hedge fund or own a private equity fund because that puts them in a different business.

Can we get there?

Stern: So, can we get from here to there, where commercial banks look much more like traditional commercial banks, and we leave things like proprietary trading and hedge fund activity and those kinds of things to other institutions? Can we get back to that kind of world?

Volcker: Well, I think we can, but obviously there’s a lot of opposition among banks. I actually don’t think it’s nearly as difficult as you might think. There aren’t many banks that own hedge funds or private equity funds. Where you do run into a problem is with trading, and there they’ll say, “We can’t serve customers; we can’t do underwriting without some trading activity.”

I think that’s right, but I think there’s a difference between that kind of activity—it’s probably a matter of scale—and what, let’s say, Goldman Sachs and some of the other banks are doing, where it has become a very major preoccupation, profitable or not.

I must say that when I talk to people in these institutions—people I know pretty well and trust—they say, yes, there is a difference between aggressive proprietary trading and the kind of thing that emerges in the context of customer relationships.

It’s only partly a prudential problem—particularly at a bank that has a large investment management business (and, of course, the big ones do). The problem is that it’s just an obvious conflict of interest between the hedge fund, the trading and the private equity business in what they’re doing advising their customers.

Stern: Right, right. Although they presumably have some sort of Chinese Wall.

Volcker: Well, I believe they have a Chinese Wall; I don’t believe those walls are impermeable.

Too big to fail

Stern: You alluded earlier to something I wanted to get back to. I hear your desire to avoid designating institutions that are automatically too big to fail.

Stern: You alluded earlier to something I wanted to get back to. I hear your desire to avoid designating institutions that are automatically too big to fail.

But the question is, can you create enough constructive ambiguity so that people in the marketplace have reasonable uncertainty about which financial institutions might be considered too big to fail—especially in light of the stress tests, which obviously designated 19 institutions (certainly those 19) as likely to be on any such list?

Volcker: Well, we are in the middle of the crisis. I’m not thinking you can have a very strict rule delineating between those that are too big to fail and those that are not. In the current stressful situations, it’s probably not very realistic.

But let’s assume that we’re returning to a situation where we don’t have emergencies every day, and you might have a fairly isolated case as with Long-Term Capital Management. You need some instinct as to how to handle that particular situation. My point is the instinct should be one way if it’s a strongly regulated bank within the official “safety net” and another way if it’s not a bank.

I don’t think we can live with a situation where an investment bank keeps a banking license while doing things that are properly done by an investment bank. Or take a General Electric or other industrial companies with a large finance affiliate. Should we be protecting General Electric? It’s certainly not a bank in any traditional sense, but it’s a big financial business. Do you want to get into the business of directly or indirectly supporting General Electric?

Take a General Electric or other industrial companies with a large finance affiliate. Should we be protecting General Electric? It’s certainly not a bank in any traditional sense, but it’s a big financial business. Do you want to get into the business of directly or indirectly supporting General Electric?

Stern: Yes, those are very difficult public policy issues. Other things equal, it would have been nice not to have intervened in Long-Term Capital Management, even on the periphery, but that’s water over the dam now.

Volcker: Well, we are going to have, let’s assume, the systemic overseer who’s going to make judgments and say, look, some of these nonbank institutions are going off the deep end, and they have to be corralled with capital requirements or leverage requirements. I ask people, I do a little private quiz. I say, “Outside of banks, real banks, how many really systemically significant institutions are there in the world?”

Stern: Outside of real banks?

Volcker: Outside of traditional banks.

Stern: Probably not many.

Volcker: It’s surprising. You’d think there would be a lot, but the answer I typically get is maybe 20, 30.

Stern: Right. I bet it would be hard to even name 20, quite honestly.

Role of the Federal Reserve

Stern: Let’s talk a little bit more about the role of the Federal Reserve, especially if regulatory reform proceeds in one way or another. That among other things is likely to lead Congress to take a look at the Federal Reserve, especially in light of all the action over the past two years with regard to the 13(3) provision of the [Federal Reserve] Act. What advice would you offer, to people both inside the Fed and outside?

Volcker: That’s a very difficult question. It’s hard to believe the Federal Reserve Act would not be looked at after all that’s happened. On the other hand, once you begin looking at it, you realize it’s a very peculiar piece of legislation. Through the years, it has acquired a few barnacles, some legacies of history that may seem inappropriate.

On the other hand, it’s become part of the American financial structure and thinking. It’s got close relationships around the country and all those things that we’ve been preaching about: independence, expertise, continuity. Once you begin pulling back and questioning some apparent anomalies, like why we have private directors of the 12 Reserve banks, the threads begin coming apart.

The issue that’s more front and center at the moment is, of course, this feeling that was in the paper this morning that the Federal Reserve has not done a good job of supervision. That view was expressed very forcefully by a private sector group, which includes both big investment institutions and old SEC people, who don’t kneel down to the Federal Reserve quite so readily as some others do.1

There’s no doubt in my mind that the attention the Federal Reserve has paid to regulation has gone up and down over the years, depending upon both the intellectual and market environment, and the personalities involved. At a minimum, we’re going to need some reorganization of the system to more clearly focus responsibility for the regulatory side of the house. I suggested some time ago that it’s a fairly simple thing to do.

If you’re going to have an important supervisory responsibility, get a vice chairman of the [Federal Reserve] Board, a second vice chairman—a vice chairman for regulatory matters—so you can point your finger of responsibility much more directly than has been the case in the past. That would be a very minimal but important kind of thing.

If you’re going to have an important supervisory responsibility, get a vice chairman of the [Federal Reserve] Board, a second vice chairman—a vice chairman for regulatory matters—so you can point your finger of responsibility much more directly than has been the case in the past. That would be a very minimal but important kind of thing.

Stern: Right, but that could be helpful because then we’d know who is accountable for successes or failures. Right now, responsibility and authority are pretty widely dispersed.

Volcker: I would certainly do that. For my favored approach of having the Federal Reserve as the systemic overseer, there ought to be somebody in the Federal Reserve that sees that as his primary responsibility.

Monetary policy

Stern: Let’s shift gears a bit and go to monetary policy. Obviously, interest rates are as low as we can get them, at least at the short end of the curve. And we’ve done a lot of things to try to enhance liquidity to drive other interest rates lower as well. Describing it is easy, but I guess I’m wondering about its prospects in terms of both effectiveness and changing course, which undoubtedly will be necessary some day.

Volcker: Well, I asked you and others a question, I think, some months ago as to why the Federal Reserve is paying interest on excess reserves.2

Stern: You did. I don’t think anybody gave you a good answer.

Volcker: No, the answer was “go ask Don Kohn” [vice chairman of the Board of Governors].

Stern: Right.

Volcker: But since then I’ve been better instructed. I’m told that the Web site still says the purpose is to maintain tight control over the federal funds rate, but the explanation I hear now is that we’ve got all these excess reserves in the system, and if we want to tighten up, the subtle way of doing that is to raise the interest rate on excess reserves.

Stern: Yes, put a floor under interest rates.

Volcker: But right now all the talk is, we’ve got to get more liquidity in the system and encourage banks to lend.

Stern: But the markets do seem to have improved, and indeed, a lot of financial institutions have been able to raise capital, either equity or debt, without government insurance, so some of those conditions clearly have improved.

Volcker: I don’t think there’s any question about that, but, of course, this all comes in the wake of the government’s demonstrating a capacity and willingness to come to the rescue when we get into trouble. One of the really unusual things about this is that we’ve always assumed that subordinated debt is part of the capital structure, which will be impaired like equity if the situation gets that bad. But now we seem to feel a great urge to protect debt however junior, and indeed a certain urge to protect equity holders.

Stern: There hasn’t been much of that, has there?

Volcker: Well, obviously, they haven’t been protected 100 cents on the dollar, but nobody has demanded that when the government provides assistance they wipe out the equity holders. We seem to be very reluctant to do that.

That’s not the way it was thought to have worked.

Stern: That’s right. You get the return, you also take the risk. I certainly agree with that.

Well, obviously, [equity holders] haven’t been protected 100 cents on the dollar, but nobody has demanded that when the government provides assistance they wipe out the equity holders. We seem to be very reluctant to do that.

That’s not the way it was thought to have worked.

Inflation targeting

Stern: I know, or at least I think, that you have some views on inflation targeting. That issue is not on the front burner at the moment, but it could return to the front burner. And indeed, some people have argued that it would have been helpful during parts of the recent crisis because it would have helped convince market participants that the Federal Reserve was not going to permit deflation. What are your thoughts?

Volcker: I have not been in favor of inflation targeting. I just don’t like it symbolically.

Stern: Even if it were zero?

Volcker: I don’t think you have to be all that precise. If it’s zero, that’s all right. If it goes up a little during expansions, that’s all right. If it goes down a little during recessions, that’s all right. Putting all that weight on one particular price index, with all its conceptual and practical limitations …

I really squirm when I read some of these Federal Reserve statements. “The committee is concerned that inflation hasn’t gone up rapidly enough …”

Stern: [Laughter] I can understand why you might be concerned about that.

Volcker: The next sentence says, “We’re all in favor of price stability.” I say, “Look, make up your mind.” [Laughter] It’s kind of a psychological point. I did not understand, and I didn’t know how seriously the Federal Reserve really took it, whenever it was—2001, 2002, 2003, whenever—this great danger of deflation. I thought deflation at that time was about as likely as the polar ice cap melting. But it really seemed to bug people.

Stern: I must say I agreed with you. I’m on record as being much less concerned about deflation than many of my colleagues, but I didn’t succeed in persuading them that it didn’t represent much of a threat.

Misreading Japan

Volcker: It probably was a real misreading of the Japanese situation. The Japanese had an enormous deflation of both the stock market and real estate prices, much more than we had, and the banks for various reasons were largely real estate lenders and had real estate as collateral. They were really knocked for a loop. And for a little while, they weren’t very eager lenders and there weren’t many borrowers either.

[Concern in 2003 about deflation] probably was a real misreading of the Japanese situation. The Japanese had an enormous deflation of both the stock market and real estate prices, much more than we had, and the banks for various reasons were largely real estate lenders and had real estate as collateral. They were really knocked for a loop.

I interpret that as a response to the collapse of the enormous bubble that they had in the stock and real estate markets, not this impression that the proverbial Mrs. Watanabe was sitting around saying, “I’m not going to buy anything this year because prices might be 1 percent lower next year.” I don’t think that’s a realistic story. But that experience somehow got translated here as Japan had no price increases or very small price declines, and that was the cause of a terrible economy at that time.

Well, I think that’s the chicken and the egg; it’s backwards or something. If you look at that closely enough, in the early part of the 1990s, when the economy was either no growth or slight decline, prices were still going up. In the second half of the decade, prices did go down about 1 percent a year but the economy went up.

Stern: Right. There may have been an overreaction to or an overemphasis on Japan.

Asset prices

Stern: That brings up another question. As you know, U.S. policymakers generally have preferred to try to cushion the repercussions of asset price collapses rather than address asset price run-ups in their early stages. But in view of the damage that results from these collapses, I’ve begun to think we need to revisit these issues, to reevaluate the costs and benefits of reining in asset price increases that seem to outstrip economic fundamentals.

What are your thoughts on the matter? Do you think policy ought to pay more attention to asset prices and in particular to what look like bubbles?

Volcker: I think it ought to pay some attention. It’s obviously a difficult matter of judgment when you deal with it. You probably can’t do it satisfactorily by traditional monetary policy alone.

But this is why I would give the Federal Reserve some responsibility for overseeing the whole market and financial stability broadly drawn. I think the Federal Reserve has always, whether it’s explicit or not, had that role, and it ought to continue, maybe more explicitly. Then you have, or you should have after this episode, a panoply of both control mechanisms, and a willingness to use them, that you didn’t have five years ago.

Economic knowledge and central banking

Stern: You’ve obviously been involved for a long time directly with the Federal Reserve, at senior levels, from the mid ’70s and even earlier than that in the Treasury as well. In your view, has macro policy or monetary policy changed significantly over those many years? Or are we still pretty much at the state of knowledge, and is the state of our responses pretty much where it was?

Volcker: [Laughter] It’s interesting you ask that question because I recently commented to some of my economist friends that I’m not aware of any large contribution that economic science has made to central banking in the last 50 years or so.

Our ability to forecast is still very limited. The old issues of the relative role of fiscal and monetary policies are still debated. Markets are certainly more complex, and some of the old approaches toward monetary control seem less relevant. Recent events have certainly illustrated limitations in our understanding of the economy.

The advent of floating exchange rates, which partly reflects a shift in academic thinking, has certainly been important, but the underlying problems of policy seem familiar.

Right now, we are in the midst of a very large unsettled question. Are the unprecedented Federal Reserve and other official interventions in financial markets a harbinger of the future? Is reasonable financial stability really dependent on such government support?

On the technical side, there has been continuing change in the approach of central banks to the market, away from more quantitative approaches like the volume of bank reserves to much more emphasis on precise control of short-term interbank interest rates. The point is that in establishing and conducting policy, you need some means of reaching operational decisions. Those approaches have differed and evolved. But none of that breaks new conceptual ground.

Stern: Well, let me explore that a little further because I happened to be reading some of the [Federal Open Market Committee meeting] transcripts from the 1970s, after the oil price shock but before you became chairman, so neither of us was at the meetings.

Volcker: Well, actually I was at the meetings from 1975 as president of the New York Fed.

Stern: Of course, right. So these transcripts were a little earlier in the ’70s. Anyway, all the talk was about “cost-push” inflation and how monetary policy couldn’t do anything about it. That was not only the consensus in the United States, but Federal Reserve officials who were traveling in Europe and talking with their counterparts heard the same message. Looking back at that from today’s perspective, I think you’d be hard-pressed to find policymakers or economists who would accept that view.

Volcker: No, I think that’s basically true. You know, the clearest articulation of that point of view was in Burns’ farewell speech, “The Anguish of Central Banking,” which was a long lament about how the Federal Reserve couldn’t deal with inflation because of all the political and economic pressures, and wasn’t that too bad. He made that speech at an IMF [International Monetary Fund] meeting about two months after I had become chairman.

So, when I gave my valedictory speech, I called it “The Triumph of Central Banking?” I put a question mark at the end. Somebody ought to write about this, how central banks became so important in the public mind and in their own mind in the past 10 years or so. Independence of central banking became part of the approach in almost every country. And I think you can make a case that it’s been a little overdone, that central banks suffer from hubris, like everybody else.

Somebody ought to write about this, how central banks became so important in the public mind and in their own mind in the past 10 years or so. Independence of central banking became part of the approach in almost every country. And I think you can make a case that it’s been a little overdone, that central banks suffer from hubris, like everybody else.

Stern: I think that might be right, and I want to explore that a little bit, but I would say, you’re personally responsible for that, because not only did you and your colleagues at the Fed succeed in bringing down inflation, but you did so when the general consensus was that nothing could be done about inflation, that we just had to live with it. So I think your success in bringing down double-digit inflation helped to establish the significance of monetary policy and central banks.

Volcker: You know, talking about whether economists have learned anything or contributed to monetary policy in the last several decades, Chairman Bernanke gave a speech at Princeton right after he took office which was an intellectual review of economists’ views of monetary policy.

I don’t recall all the substance of it, but he said basically that economists were ahead of central bankers in understanding important issues, going back to the 1920s and before and certainly in the Great Depression. But he went on to say that there was one area where the policymakers were ahead of the economists.3

It was an interesting comment. I don’t know if he made it because he knew I was in the audience at the time. But he said something to the effect that the academic economists had to learn from central banking about the importance of maintaining a strong sense of price stability. He has translated that into inflation targeting, I guess.

The effectiveness of policy

Stern: You mention that you thought, maybe now, or certainly in the last 10 years, there was a point where we had too much confidence, too high a level of expectations for monetary policy. I’ve been thinking about that as well, because obviously we’ve had a very significant financial shock to the economy, and one of the consequences of that has been a long and deep recession, and high unemployment. You’re familiar with all this. There seems to be a view that policy, both monetary and fiscal, can somehow fix this quickly. I guess I’m very uncomfortable about that.

Volcker: I don’t think it can. I’ve been dealing with this in a political environment. The other day I’d gotten a paper prepared for the presidential advisory board that I’m the chairman of. It talked about housing and mortgages and so forth. It concluded, “We’ve got to do something to support housing,” so it recommended means of spurring mortgage creation.

But then it went on, “We’ve got to do something to support consumption.” There I begin to wonder. We can do something to support consumption, but are we really dealing with the underlying pressures in the economy without permitting a relative decline in consumption to proceed?

Stern: Right.

Volcker: It’s not an easy question, if you try to explain that. Mr. Obama is out there every day having to explain things and would he say, “Well, I don’t think I want to push a big stimulus on consumption”? I don’t think he’s about to say that, but he probably should be saying that.

Stern: The pressure seems to be now from the press I follow, “You’ve got to find policies that will create jobs,” and again, who could object to that? But it’s not obvious that there are a lot of tools that would be effective at that in the short run.

Volcker: No, I think this period we’re going through is kind of a curative process; it’s a purgative. There is something to the old view that you have to have a recession once in a while to deal with the excesses of a boom. And I think we had excesses in this boom, for sure, and we’ve got a really difficult recession. You want to relieve the sharp edges, without any question, but I don’t think it’s been possible to pump it up so there’s no recession at all.

Volcker: No, I think this period we’re going through is kind of a curative process; it’s a purgative. There is something to the old view that you have to have a recession once in a while to deal with the excesses of a boom. And I think we had excesses in this boom, for sure, and we’ve got a really difficult recession. You want to relieve the sharp edges, without any question, but I don’t think it’s been possible to pump it up so there’s no recession at all.

Stern: Yes, and part and parcel of recessions are resource reallocations. And we clearly had too many resources in housing and probably too many in finance and in autos—just to name three obvious places.

Volcker: Exactly. We need a recovery that emphasizes investment and competitiveness, and that ends or reduces our dependence on foreign borrowing.

I don’t really think the attitudes in financial markets have changed all that fundamentally. I think they were shocked, but “now things have settled down, so let’s go back and make a lot of money.” Unfortunately, I think it could take two years of problems in financial markets before they accept fundamental change.

I don’t really think the attitudes in financial markets have changed all that fundamentally. I think they were shocked, but “now things have settled down, so let’s go back and make a lot of money.” Unfortunately, I think it could take two years of problems in financial markets before they accept fundamental change.

Stern: Well, of course, we’re close to two years of some sort of problem, but the peak was probably the latter quarter of last year.

Volcker: That was the peak of the problem, for sure. But you know, the precise dating of recession is not really here nor there. Somebody sat in a room and decided the recession started in December of 2007. You could just as logically say it started in September of 2008, I guess.

Stern: That’s right. The macro data weren’t very soft until then. I think I would agree with that.

Public service

Stern: Let’s spend a few minutes on public service. I know you’ve had a long-standing interest in it, and, of course, you’ve been deeply involved in public service. And I know you’ve worked on the topic too.

As I’m reaching retirement, I’ve been thinking more about it as well, with some concern, because it seems to me that it has become harder to attract high-quality people to public service for any length of time. Do you share that perception, and if so what can we do about it?

Volcker: In the past year or so, I think that, because of the recession, because of the difficulties, because of the perceived importance of public policy, that that situation has actually changed. I don’t know how fundamental it is, but places like [Harvard’s] Kennedy School of Government, for example, have seen a big increase in applications. I think that’s true more generally.

People will consider it now and say, “Gee, I wish I was doing that.” Even my grandson! I don’t think he’s really going to do anything about it, but he does consider that maybe there’s something interesting to do in government, which I can’t imagine he would have thought before.

Basically, I agree with you. It’s a whole different attitude toward public service than it once was. I tell you, we can all sit around in our old age and moan about it, but I think the administrative processes and the management effectiveness of the federal government are terrible! It shouldn’t be that bad. They haven’t got people there to do it.

It’s a whole different attitude toward public service than it once was. I tell you, we can all sit around in our old age and moan about it, but I think the administrative processes and the management effectiveness of the federal government are terrible!

The Congress is more and more receptive to particular interests and the money-raising apparatus. They don’t seem to have any interest in administrative effectiveness, and are perfectly willing to abuse any new programs with political favors here, there and the other place.

We sit here now in July, six months after the inauguration of the president. Apart from the secretary himself, the U.S. Treasury still has no officials of the kind you think of as officials in office except a deputy secretary who isn’t very well known. We’ve got a couple of nominees who I do not think have been confirmed yet. There may be an assistant secretary or two who have been confirmed.

But basically you go through the most difficult period in financial reorganization and financial pressures and financial crisis, and the place isn’t manned in any normal way. And I think it shows. You rely on ad hoc advisers, and who they are nobody knows. And that situation is not just in the Treasury.

Stern: Yes, we’ve had two openings on the Board of Governors more or less forever.

Volcker: It’s crazy! It’s true for the Board of Governors, which is probably less sensitive so long as you have enough people; it doesn’t make much difference whether it’s seven or five or whatever. But there’s been close to an official vacuum in the Treasury department when you get below the secretary. So many things have to be decided; I mean, it’s not the way to run a government.

But there you are. There’s been no president who’s been particularly interested in this subject for years. Clinton seemed the closest, I guess, with Al Gore and his “re-inventing government” program.

New approaches on public service?

Stern: Is there some way to fix it? I must admit I haven’t had any inspirations.

Volcker: Well, I was on two big commissions that have nice reports sitting around here someplace which I can give you, but they have not sparked any revolutions.4

Stern: I know. So I’m looking for some new approaches. [Laughter]

Volcker: I’m not so sure it’s easy to have new ones, although this last commission had fresh and very sweeping proposals. But we couldn’t manage to do anything—well, nobody cares! That’s very damaging, not just in economic policy, but you go up and down the line.

Stern: It seems to me—and maybe I don’t have a sufficiently broad picture of this—that potential candidates have to really want the jobs given the process that you have to go through these days.

Volcker: The ones who really want the jobs may not be the best ones to have it.

Stern: Right, right.

Volcker: When I became undersecretary of the Treasury for monetary affairs in 1969, I could sit in my office at my desk and see the inaugural parade coming down Pennsylvania Avenue, and I was ready, with the other undersecretary, to do business. We had not been confirmed at that point, but now they say, “If you’re not confirmed you can’t go near the office; you’ve got to go hide in a corner.” And I probably got confirmed within a week or so; that didn’t make any difference: You did what you were doing.

But that was 40 years ago. You didn’t have this business of the “vetting” extended for weeks or months looking into every nanny you had or cleaning woman you had. It isn’t good. It really is crazy that you sit here with a largely unmanned government for six months. And it’ll be more than six months by the time …

Stern: Yes, I don’t know when that’s going to change under the current circumstances.

Volcker: Every report says this is a problem, and nobody ever does anything about it. It’s discouraging. I’ve given up; I’m not going to chair any more commissions on public service, even if I survive this cold.

Stern: Sounds like a good decision to me.

Reform of the Fed

Volcker: As far as what should happen to the Federal Reserve, there have been a few agencies that have been somewhat exempt from what we’ve been talking of, and the Federal Reserve is certainly one of them. There aren’t very many. I’d be hard pressed to think of another. If the net result of all this is to kind of tear the Federal Reserve apart and upset all this intricate structure that it has …

Well, as I said earlier, I think what should be done is that somebody on the Board, not just by designation of the chairman—whether he does it well or does it poorly—somebody on the Board ought to have responsibility [for supervision], confirmed by the Senate, so they can go and say, “You screwed up.”

Stern: I like that idea. I think it makes a lot of sense. On a related matter, I think the stress tests went well, and I think that was a plus all around. But they had a very particular focus in crisis circumstances. A more challenging thing is, when everybody is making money hand over fist, where they’re taking a lot of risk, can you do anything about that in a timely way?

Volcker: That’s where the rubber hits the road! That’s the big challenge for monetary policy—how to damp down the party before it gets out of hand.

Stern: That’s right. That’s the challenge.

Volcker: And then you’ll see a [Paul] Krugman op-ed piece, “What’s the Federal Reserve doing, tightening up?! Unemployment is still 9 percent!”

Stern: Tightening up? What have we tightened up? [Laughter]

Volcker: I’m talking about when you do.

Stern: Oh, yes, that day is coming. You can see it with all this pressure for a second round of fiscal stimulus. And, well, you know better than anybody: You start tightening policy, and there are going to be lots of objections about, “It’s premature and everything is still fragile” and so on and so forth. And I would argue—we’ll see if you agree—that it was exactly that kind of thinking, aided by concerns about deflation, that led to the housing bubble, in part.

Volcker: Absolutely! But we can sit on the outside and gripe, “We would have done it right, but the new guys are …”

Stern: [Laughter] Sure! And we’ll see if anybody believes us.

July 15, 2009

More About Paul Volcker

Positions

- Professor Emeritus of International Economic Policy, Princeton University, current

- Henry Kaufman Visiting Professor, Stern School of Business, New York University, 1998–99

- Chair and later CEO of Wolfensohn & Co., 1988–96

- Chair of the Board of Governors, Federal Reserve, 1979–87

- President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1975–79

- Undersecretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs, 1969–74

- Vice President and Director of Forward Planning, Chase Manhattan Bank, 1965–68

- Deputy Undersecretary for Monetary Affairs, U.S. Treasury, 1963

- Director of the Office of Financial Analysis, U.S. Treasury, 1962

- Financial Economist, Chase Manhattan Bank, 1957

- Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1952

Service

- Chair, Independent Review Panel, World Bank Department of Institutional Integrity, 2007

- Chair, Independent Inquiry into the United Nations Oil-for-Food Program, 2004–05

- Chair, Commission on the Public Service, 2003

- Chair, Board of Trustees of the International Accounting Standards Committee, 2000–05

- From 1996 to 1999, Volcker headed a committee formed to determine existing dormant accounts and other assets in Swiss banks of victims of Nazi persecution

- Also associated with the Japan Society, the Institute of International Economics, the American Assembly and the American Council on Germany.

- Honorary Chair of the Trilateral Commission and Chair of the Trustees of the Group of Thirty

- Has served on numerous public and private advisory boards

Education

- London School of Economics, 1951–52

- Harvard University, M.A., 1951

- Princeton University, B.A., 1949

Endnotes

1 See “U.S. Financial Regulatory Reform: The Investors’ Perspective,” Investors’ Working Group Report, Council of Institutional Investors, July 2009. Online at cii.org.

2 The question was asked at the Financial Markets Research Center Conference, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., April 18, 2009.

3 Chairman Bernanke said, “Until this point, academic research (or at least some of it) had paved the way for improved policymaking. After 1979, however, policymakers increasingly began to set the intellectual pace. Volcker’s statements from this period in particular are remarkable in the extent to which they anticipate contemporary thinking about the crucial importance of low and stable inflation and inflation expectations.”

See “The Benefits of Price Stability,” a speech by Ben Bernanke at the Center for Economic Policy Studies, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., Feb. 24, 2006. Online at federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20060224a.htm.

4 See “Urgent Business for America: Revitalizing the Federal Government for the 21st Century,” Report of the National Commission on the Public Service, January 2003. Online at brookings.edu.