Recently released data from the 2007 Census of Agriculture appear, at least on the surface, to tell a different story. According to U.S. Department of Agriculture figures, the number of farms increased 4 percent nationwide compared to the previous census five years earlier. The farm count grew in 39 states, including almost every state in the Ninth District.

In a press release the USDA said that the new census "indicates a leveling" of the decades-long decline in the number of farms—cause for optimism for those dismayed by the plight of the family farmer.

However, a closer look at the data shows that the historic pattern persists. The number of very large farms has increased, while the decline in medium-sized, family-run operations has continued unabated. In many parts of the district and nation, they are giving way to increasing numbers of small holdings, often dubbed "hobby" farms.

Families are still farming, but they have more in common with the folks in Green Acres than those in Little House on the Prairie.

The incredible shrinking farm

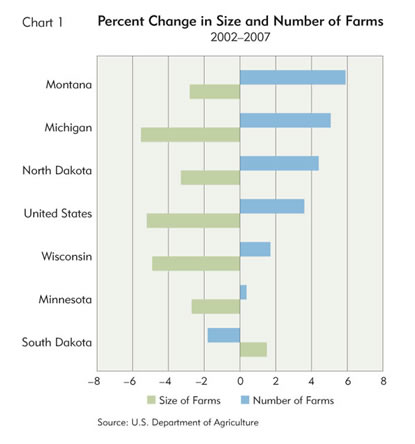

Two main findings—a surge in the number of farms and a commensurate drop in average farm size—jump out from the ag census data. Between 2002 and 2007 the number of farm operations increased in every district state except South Dakota (see Chart 1). County-level data in the census show that the number of farms increased in 173 out of 303 district counties. While that leaves dozens of counties where operations fell in number—due to urbanization and farm consolidation—the percentage decreases in these counties were generally smaller than the proportional increases in counties where farm numbers rose.

Over the same period the acreage of farmland mostly decreased or stayed constant in district states (see Chart 2). Urban areas have continued to expand, consuming surrounding farmland. Farm acreage increased slightly in Montana and North Dakota, largely due to greater cultivation of marginal land because of high crop prices in 2007. Nationally, farm acreage declined more than 3 percent.

More farms and static or decreasing farm acreage implies that, on average, farms are getting smaller. This is the case for every district state except, once again, South Dakota. In many areas the proliferation of hobby farms—properties classified by the USDA as "retirement" or "residential/lifestyle" operations—is shrinking average farm size. The owners of these farms are either retired or earning most of their income in nonfarming occupations. While these properties make up almost 60 percent of U.S. farms, they account for less than 10 percent of agricultural sales.

A good example of the spread of hobby farms is the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where despite the region's thin soils and frigid climate, some counties have seen 20 percent or higher increases in farm numbers. The number of farms in Luce County, Mich., increased from 30 in 2002 to 41 in 2007. Many of the new farmers are former residents of nearby U.P. cities like Sault Ste. Marie or urban centers in the Lower Peninsula who are more interested in a rural lifestyle than commercial farming.

"Most of those are probably small and part-time farmers—people moving out from the city and buying a 40- or 10- or 20-acre plot and then doing farming on the side," said Warren Schauer, a Michigan State University extension educator based in Escanaba. Counties farther west in the U.P. are apparently in less demand for hobby farming; there the number of farms mostly fell or held steady.

Instead of potatoes, hay and dairy products—the primary output of commercial farms in the U.P.—many of these small farms produce food for personal consumption or for sales at farmers markets and specialty shops.

Similar patterns of rising farm numbers can be seen in other district counties near urban or recreation areas. In Rice County, Minn., near the Twin Cities, the number of farms increased 15 percent, while acres per farm decreased 12 percent. In Montana, the state with the district's biggest percentage rise in farm numbers, Glacier County near Glacier National Park saw a 32 percent increase in farm operations and a 22 percent drop in average acres.

An analysis of farm income in district counties supports the presumption that operations formed in the past five years are predominantly small farms with relatively low output. Although farm income increased overall, it grew significantly less in counties where farm numbers increased.

Feeling the squeeze

While it appears that most newer farms are smaller, many large-scale operations in the district are growing even larger. In many counties big operations have absorbed smaller ones in recent years, creating fewer, more expansive farms with over $250,000 in annual sales.

Across the district, the biggest farms account for a greater share of agricultural output today than in the past. In Montana the top 13 percent of farms measured by sales produced three-quarters of the state's agricultural output in 2007. Ten years earlier that share of farm sales was spread over the top 20 percent of operations by sales. Compared to the district, national farm output is even more concentrated at the top.

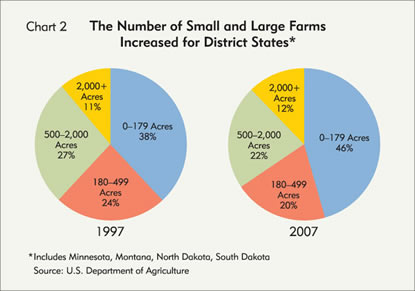

The number of medium-sized family farms that fills the gap between factory operations and hobby farms has been falling for years, and the latest census shows that they continue to fade away. "It's actually a bimodal change; we're seeing growth in the big and the small at the expense of those in between," said Richard Rathge, a rural demographer at North Dakota State University.

Take North Dakota, for example. Between 1997 and 2007, the number of farms under 180 acres in size increased by nearly a third and the number exceeding 2,000 acres increased 7 percent. In the same period the ranks of farms between 500 and 2,000 acres—the size of a typical commercial family farm in the Dakotas, Rathge said—shrank by more than one-quarter.

In Minnesota the number of 2,000-plus acre farms increased even more, by 18 percent. The pattern is especially evident at the county level; in many areas, such as the sparsely populated southwest, farms became larger and less numerous.

Despite a statewide decline in the number of farms and increasing average farm size in South Dakota—counter to the trends in the rest of the district—there was no reprieve for medium-sized farms in the state. The number of operations between 500 and 2,000 acres in size fell almost 14 percent, reducing the total number of farms even as the number of large and small operations grew.

The latest ag census numbers show, as the USDA stated in its press release, a break with the past: Nationally and in most district states, the number of farms is increasing. The long-term effects on agricultural production and rural communities of an influx of small-scale farmers who don't fit the traditional farming mold remains to be seen. Less dependent on the land for a living than the archetypal family farmer, they produce an array of food products that are difficult to categorize and quantify.

However, the overarching historic trend in agriculture hasn't changed; among commercial farms that produce the bulk of the nation's food, farms on average are getting bigger and fewer.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.