In a suburban Minneapolis building where Tonka Toys trucks were once made, a pile of scrap plastic reaches for the ceiling. Accumulated by recycling firm Choice Plastics, the hoard contains enough discarded material to make thousands of toys, plumbing parts, milk jugs and other useful items.

If the stuff doesn't end up in a landfill first.

Choice Plastics' problem, shared by recycling operations across the nation, is that the global recession has caused an overall drop in demand for commodities, including recyclables. Some materials have become worth less than the cost of storing them. Dramatically lower prices for scrap plastic have led to a “big fallout” for businesses such as Choice Plastics, said Art Speck, co-owner of the Mound, Minn., company. Last November, revenue was down 60 percent from the firm's monthly average to date in 2008.

The precipitous drop in demand has hurt the balance sheets of other recycling and recyclable processing firms in the Ninth District, including G&G Recycling of Dickinson, N.D., which closed its doors in December after more than 30 years in business, citing a shrinking market for its output.

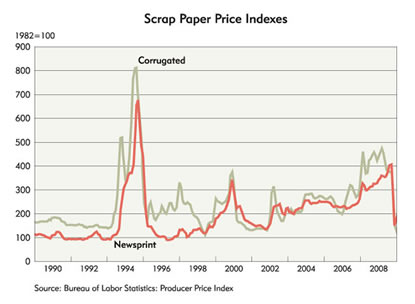

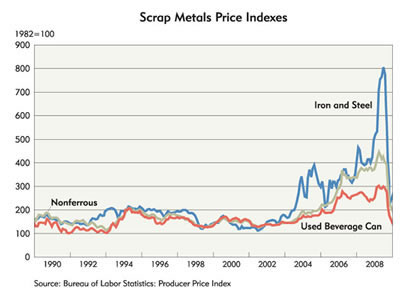

After rising over the past few years and climbing steeply in early 2008, market prices of most recyclables dropped sharply in the second half of last year. The price of scrap aluminum cans, for example, fell 49 percent between July and December. The price of scrap paper fell 52 percent in the same period (see charts below).

While these steep declines have hit recycling businesses hard, there's still a viable market for recyclables, and no shortage of firms continuing to amass and sell discarded materials. Recycling in the Ninth District is largely a regional business, but global markets and prices have a major impact.

The prospects for district recyclers depend on long-term global demand for commodities, which remains uncertain. Firms suffering from low prices today can take heart from the fact that the industry has survived previous episodes of falling prices.

Garbage in, cash out

Recycling is often viewed as a public service, but over the years it also has become big business. Nationwide, about 2,400 recycling facilities employ 50,000 workers and recycle about 165 million tons of material annually. Comparable figures aren't available for the district, but in Minnesota an estimated 6,500 people work in the industry, according to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA).

Recycling encompasses more than post-consumer waste—what sits out on the curb on pickup day. The bulk of recycled material comes from commercial sources: leftovers from the manufacturing process, or cardboard boxes and other packaging discarded by retail stores and warehouses.

Rather than pay to get rid of their waste, businesses sell it to brokers who pick up on site. Depending on the material, scrap might be processed by the broker or resold to other processors. In either case, recyclables such as corrugated cardboard and aluminum cans are transformed into the raw materials for new goods—everything from toys to cereal boxes to medical devices.

Choice Plastics bales and sells about half the plastic it collects, while processing industrial plastic scrap into “regrind”—pellets similar to fresh plastic resin that provide a lower-cost substitute for virgin materials. Material from municipal recycling programs often requires additional handling and processing, but ultimately it too becomes grist for new products.

National processors of municipal waste such as Waste Management Inc. and Allied Waste typically sell their material on a contract basis to paper mills, aluminum factories and other major consumers of raw commodities.

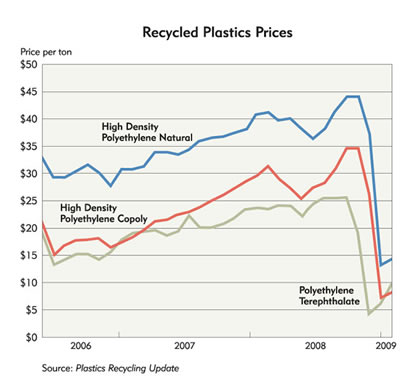

Thanks to the varying demands of manufacturers and the great variety of sources of scrap, the recycling market comprises a broad array of materials. In the plastics segment, milk jugs, soft drink bottles and chemical containers are made of different kinds of plastic, and each type commands a different price depending on its color and whether recyclables are sorted, baled or reground (see chart below).

Prices of many of these recycled materials rose in this decade, then soared in early 2008. In July, scrap steel was selling for $550 per ton, nearly twice the price it commanded a year earlier. That trend abruptly reversed last fall, as prices plummeted in response to evaporating demand. One of the main drivers of this volatility was huge swings in demand for recycled materials in China, until recently a voracious consumer of commodities.

The China syndrome

Driven by a massive construction program and rapidly growing manufacturing, China's prodigious appetite for raw materials has driven up global prices of steel, lumber, oil and other commodities for years. Because recyclables are substitutes for fresh raw materials, their prices rose as well, and China was also importing a lot of scrap material from the United States. Those plastic bottles Choice Plastics bales for processors? Most of them were bound for China, to return in the form of television sets, MP3 players and other consumer goods.

“Recycling's growth in this decade, which has been very good, has been essentially due to growth in Chinese demand,” said Jerry Powell, executive editor of Resource Recycling magazine in Portland, Ore.

U.S. recyclers also benefited from low rates for scrap shipments to China; the country's trade surplus with the United States meant that there were always empty freighters in West Coast ports in need of ballast for the return trip to China.

Coming on top of domestic demand, China's heavy consumption strained the supply of recyclables in the United States, causing a surge in prices. In commercial recycling, most of the low-hanging fruit—scrap from factories, warehouses and big-box stores—had already been picked. Powell believes that the law of diminishing returns—each additional ton of industrial scrap was more expensive to extract than the last—led to the spike in recyclable prices in early 2008. It was difficult for municipal recycling programs to pick up the slack; only about 40 percent of containers and packaging are recycled in the United States.

However, later in the year, China lost its appetite for imported recyclables. Manufacturing was slowing, and unsold goods were stacking up in warehouses. In November, the Chinese government shut the door on further scrap shipments from the United States. “There were loads of recyclables that were on their way to China that were unable to dock,” said Wayne Gjerde, recycling market development coordinator for the MPCA.

The sudden drop in demand triggered a downward spiral in scrap prices that has been exacerbated by a slump in U.S. manufacturing and sinking prices for other commodities. By the end of last year, factory output had suffered its worst contraction in nearly 30 years, according to the Institute for Supply Management's manufacturing index. A decline in manufacturing means less demand for inputs, including recycled materials.

Also, declining prices for basic commodities such as oil and timber have cheapened recyclable materials that serve as substitutes. Take plastic, for example. Last year's big decline in the prices of oil and natural gas has lowered the price of recycled plastic, because it is a substitute for virgin resin made from those commodities. When resin gets cheaper, there's less demand for recycled soft drink bottles and milk jugs.

No place like home

But not every part of the country has suffered equally from the free fall in global recyclable demand and prices. Recyclers in the district, especially those in Minnesota and Wisconsin, enjoy an advantage over firms in coastal regions: They're less dependent on Chinese demand, thanks to the presence of large processing mills such as the Rock-Tenn Co. paper recycling plant in St. Paul and a Waste Management processing plant in Superior, Wis. Most of the recycled material in the eastern part of the district is processed close to home and eventually sold to manufacturers.

“We're fortunate in that we have a lot of local markets,” Gjerde said. “Many states-Montana, North and South Dakota—don't have that.” He added that recyclers in Minnesota and Wisconsin recently have been commanding slightly higher spot prices than those offered on the West Coast.

For recycling firms in the western part of the district, the glass is half full—or half empty. Like recyclers in Minnesota and Wisconsin, they haven't been affected directly by the meltdown of the Chinese market, because exports to China have never accounted for much of their business; it's expensive to ship scrap by rail hundreds of miles to Pacific ports. But a scarcity of processors in Montana and the Dakotas means that shipping costs are still relatively high—costs that are hard to justify at today's low prices for recyclables.

“There is not a lot of money in cardboard and paper, so when you start having to take shipping costs out of that, it makes it worse,” said Bob Morrow, manager of Valley Recycling, a collector and broker in Kalispell, Mont. The company sends its wastepaper and other types of scrap to processors in Washington state; Morrow said he recently shipped out scrap at a loss.

Recyclers in North and South Dakota, where there are no large-scale processors, must make similar tough choices; many ship their materials to processors in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Even though the district is insulated to some extent from the problems afflicting coastal recycling markets, there's no denying the industry has fallen on hard times of late. In addition to closings like G&G Recycling, recent months have seen numerous firms cut back operations. For example, last fall Yellowstone Recycling in Glendive, Mont., stopped accepting any material other than newsprint.

Speck, of Choice Plastics, said the folding of other brokers has brought more business his way: “We're getting calls regularly from people that we've never talked to before who have material to sell.”

Kicked to the curb

The turmoil in the recycling business has raised concern about potential environmental consequences. Since last fall's big price drop, more recyclable waste has ended up in landfills. Minnesota law stipulates that collectors for municipal recycling programs cannot dump materials in landfills without special permission from the state. So far, none has been requested. Given current tipping fees at landfills, it often still makes financial sense to sell scrap rather than haul it to the dump.

In other district states, it's easier to get away with dumping, as there are no statutes explicitly outlawing the disposal of scrap in landfills in Montana or the Dakotas. But even in Minnesota, some material is finding its way into landfills. Speck admits that he has resorted to dumping some types of commercial plastic scrap, which is legal.

Morrow said he tries not to dispose of recyclables—but he has dumped commercial tin because the price of tin scrap has fallen so low that it's not worth storing it. Several other recyclers in the district said they've noticed more recyclables headed to the dump—an observation supported by an informal survey of landfills: Most have increased their tipping fees over the past six months in response to greater demand.

Another concern is the impact of low scrap prices on public recycling programs. Ellen Telander, executive director of the Recycling Association of Minnesota, said that while many mandated city programs are funded by taxes, in recent years some programs generated enough revenue from scrap sales to support themselves. Today much of that cash flow has dried up.

How falling prices affect municipal programs depends on how they are funded. “If they relied on those revenues to support their program, obviously that's an issue,” said Gjerde, who noted that some programs are considering charging higher fees to households. But declining trash values are unlikely to end public recycling. There's still a market for post-consumer waste, just at much lower prices—putting municipal programs under the same strain felt by commercial recyclers.

Everybody in the industry is wondering how severe and drawn out that strain will be.

Waiting for the upside

Few in the industry doubt that China will resume buying large quantities of scrap, pushing up prices once again. Gjerde noted that China lacks sufficient domestic lumber production to meet its needs—needs that will increase dramatically when the country's manufacturing kicks back into gear. “In order to make paper, China needs recycled cardboard and paper, and mostly from us,” he said.

When demand will pick up again is less certain. Fear of prolonged recession has led manufacturers in China and around the world to cut back materials orders, and that's unlikely to change until recovery is in sight. However, a November analysis by Cannacord Adams, a Canadian investment broker, was bullish on the long-term prospects of recycling companies, despite declining scrap prices. The company predicted that prices will stabilize this year and increase in 2010.

Powell cited a similar time frame, noting that declining consumer purchases have reduced the supply of recyclable materials, which will eventually put upward pressure on prices. Speck, too, is confident that prices will head back up, but he doesn't think price trends will become clear until later in the year.

In the meantime, recyclers will try to muddle through, finding customers where they can and charging what the market will bear. A functioning recycling industry existed before prices soared; firms that entered the business to take advantage of those prices will have to adapt or fail.

After all, the industry has endured price troughs in the past. When prices for scrap paper, cardboard and plastics plummeted in the mid-1990s, many recycled materials effectively traded for less than nothing. Then the cause was largely a supply glut resulting from successful new recycling initiatives. Within two years, prices bounced back as inventories dropped, commodity prices rose and more processing capacity came online.

“We've been through this type of thing before,” Powell said. “The difference is, in the nineties it was our fault; this time it's beyond our control.”

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.