Perched at the busy intersection of Interstate 35W and Washington Avenue on the edge of downtown Minneapolis, Bobby & Steve's Auto World had built a small but growing stream of customers stopping in to buy E85, a fuel blend of 85 percent ethanol and 15 percent gasoline.

Lately, however, E85 business has disappeared as the price of gas dropped, said Gerald Scheeler, the station's operations manager. “Our peak volume was when gas was $4 a gallon. We've probably experienced a 50 percent drop in sales.”

Once seen as a promising alternative, E85 has struggled to become a mainstream fuel in the United States. A decade after its introduction, the blend has failed to find much of an audience, even in Minnesota, which boasts the highest number of E85 pumps in the country and devoted endorsements from the Legislature and Gov. Tim Pawlenty.

Reasons for sluggish growth are many—none more important than the recent decline in regular gas prices, which makes E85 less economical for the consumer because ethanol delivers fewer miles per gallon. But other matters also have influenced E85 demand.

For example, the number of flex-fuel vehicles on the road that can run on the mostly alcohol blend is small, which leaves station owners wondering why they should invest in a fuel few customers can buy. As a result, E85 is not widely available at retail fuel stations. Retail penetration is complicated further by the fact that a battle-tested, industry-accepted pump for E85 also has failed to materialize, slowing expansion into chain petroleum stations—not just for E85, but also for ethanol blends between 10 percent and 85 percent, which might hold the most promise for ethanol consumption.

Skid marks

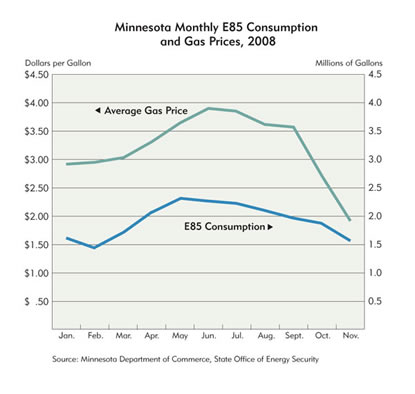

Like many things in 2008, the ethanol market didn't appear headed toward this predicament by year's end. High gas prices led to strong consumption through the first three quarters, and annual E85 use has been on the rise. Minnesota consumed 21.4 million gallons of E85 in 2007, up from 17.8 million the prior year. E85 volume in Wisconsin is considerably smaller (an estimated 6 million gallons in 2008), but has grown more than eightfold since 2005. In North Dakota, sales of E85 jumped from 528,000 gallons in 2007 to 817,300 gallons from January to October of last year.

Those numbers might seem large, but E85 represented just slightly more than 1 percent of the gas sold in Wisconsin and 3 percent in Minnesota. At Bobby & Steve's, E85 makes up 2 percent to 4 percent of gasoline sales—above average for E85-friendly stations. But as Scheeler said, "It's still a pretty small number."

The biggest influence on ethanol consumption is the price of gasoline. Since E85 gets an estimated 12 percent to 20 percent less mileage than regular gasoline, its price typically needs to be at least 20 percent less for consumers to consider purchasing it, said Scheeler. E85 prices generally track in the same direction as gas, but the price spread widens as gasoline prices rise. E85 sales soared in June 2008 when gas was $4 a gallon and E85 was $2.50 a gallon in Minnesota—a price differential of 37 percent. But that price differential crumbled to 7.3 percent nationwide by January 2009.

“The price of gasoline is so low and the price of ethanol so high, it leaves us with a lot of E85 stations not selling much ethanol,” said Phillip Lampert, executive director of the Jefferson City, Mo.-based National Ethanol Vehicle Coalition (NEVC). “We're in a different situation now (than in summer of 2008), especially with higher levels of ethanol blend.”

Gary French, general manager of the Sioux Valley Cooperative, watched as E85 gained traction last year until gasoline prices fell. “You have to have about a 40- to 50-cent spread to entice people to use it-that's what we've seen, anyway,” he said. In December, the price spread at his station in Watertown, S.D., had fallen to 19 cents a gallon ($1.47 versus $1.66); nationally it was about 13 cents.

Pump problems

Even die-hard E85 users can't just roll up to any gas station and get a tank of corn hooch. In fact, only 1,900 stations nationwide sell E85—a penetration rate of little more than 1 percent. Consider the country's two most populous states: California has just 10 stations with E85; Texas, a mere 26.

The spread of E85 pumps is better—though still paltry—in the Midwest because of its ethanol culture. Wisconsin, for example, has 120 or so stations with E85 pumps, including four in Eau Claire—still just 3.4 percent of the state's 3,500 retail stations. South Dakota has 73 stations, North Dakota has 31 and Montana has four, according to the NEVC.

Minnesota offers the best E85 distribution network by far, with more than 370 pumps and Internet maps of where they are located, good for trip planning. Yet even in the Shangri-La of E85, Pawlenty backpedaled last year on his once optimistic prediction that the state would have 1,800 E85 pumps by 2010.

Various monkey wrenches hamper the development of higher E85 demand. Aside from gas prices, the biggest is the scarcity of flex-fuel vehicles on the road. Among Wisconsin's 6.6 million registered vehicles, only 142,000 are FFVs, according to the state Office of Energy Independence. In Minnesota, despite more numerous E85 stations, there are only 175,000 or so FFVs.

“For any new fuel, it's difficult. It's the chicken and egg issue—which comes first, the flexible-fuel vehicles or retailers?” according to Robert Moffitt, spokesman for the American Lung Association of Minnesota, a major player in advocating for E85 and for assisting stations in adding E85 pumps to their operations.

"It's a Catch 22—retailers say we don't want to put in more stations until we see more vehicles, and vehicle manufacturers say we need more stations before we can produce more vehicles," he said.

Ironically, many of the 6 million FFVs nationwide that ply the roads have never seen a drop of E85 in their tanks. Part of that is attributable to the paucity of fueling stations. But many FFV owners are unaware that they have such a vehicle; until fairly recently, FFVs carried no distinctive markings to remind consumers that they can fill up with E85. In 2007, Detroit automakers began adding yellow E85 stickers and yellow gas caps to many FFVs. Perhaps not surprisingly, a General Motors study in 2007 showed that nearly 70 percent of FFV buyers had no idea they were driving an FFV.

Detroit's initial foray into FFV manufacturing also may have contributed to the lack of consumer acceptance. Just a few years ago, FFVs came in one flavor: trucks. Critics have argued that automakers saw it as a strategy to exploit a loophole in the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards that gave automakers a quick and easy way to score tax credits. This year, however, automakers offer more than 50 FFVs, from SUVs to small trucks and cars such as the Chevrolet Impala. The list offers a richer variety than ever before, but it still favors heavier vehicles over mid-sized and small autos.

FFVs have also taken a back seat in the environmental spotlight. For example, the North American International Auto Show, the industry's premier event in January in Detroit, featured 38 FFVs, an impressive number, but the media buzz was mainly around electric cars. Similarly, hybrids were the topic of considerable attention during the recent hubbub over a Big Three bailout. And given the current state of car sales, it's hard to imagine FFV sales growing much in the near term.

Without a sizable fleet of FFVs out on the road thirsty for E85, a market cannot flourish. "It's a difficult sell … because you have to have the right car and find the right station and the right pump at the right price. That's pretty demanding from a market perspective," said Ralph Groschen, senior marketing specialist at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

Advocates also believe that the sluggish uptake of E85 can be traced back to the lack of an E85 dispenser approved by Underwriters Laboratories, whose ubiquitous UL symbol can be found on hundreds of thousands of appliances and products. Many station owners are reluctant to sell E85 without UL-approved equipment.

“My understanding is that big-box stores like Wal-Mart were prepared to put in islands for gasoline with E85, but when UL made it public they had not formally approved any approach on E85, it was dead for big-box merchants,” said Groschen. Stations generally are not required by law to have UL-approved pumps—and if they are, waivers are sometimes available. But many want them for reasons of liability.

Ron Lamberty, vice president for market development at the American Coalition for Ethanol in Sioux Falls, S.D., said he's heard no complaints from stations selling E85 in pumps without UL certification. Still, many station owners don't want to risk not having UL-approved pumps because of insurance and safety concerns. Early reports say E85 pumps may cost $7,000 to $9,000 more than traditional pumps (which cost roughly $10,000 to $15,000) due to the need for specially plated surfaces within the pumps to prevent the corrosive effects of ethanol, he said.

John Drengenberg, UL's consumer affairs manager, said standards for testing were released in October 2008 and pump manufacturers have submitted equipment, mainly dispensers, for testing. No manufacturer, however, has provided a complete accompaniment of parts necessary for an E85 pump. The organization is being careful with testing because alcohol corrodes equipment much differently, and more quickly, than petroleum, said Drengenberg.

Breaking the blender wall

Oddly, many see the ethanol market as either E10 (a staple at gas stations nationwide) or E85, when in reality the "E-market" can be any blend in between. The ethanol industry believes that government policy has created a "blender wall" forcing consumers to buy, and station owners to sell, either E10 or E85.

Very slowly, the lid is getting lifted off this market. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has given Clean Air Act waivers to the Dakotas, Minnesota and Wisconsin to sell E15, E20 and other blends to FFV drivers who, in general, have reported better mileage using those blends than E85. And the federal energy act passed in 2007 encourages the development and sale of vehicles able to use higher blends than E10.

In fact, there is evidence that in-between blends offer decent mileage and cleaner emissions. A widely cited 2007 study, cosponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy and the American Coalition for Ethanol, found that vehicles without any adjustments operated better than expected—including gas mileage—on higher ethanol blends, suggesting that the optimal ethanol-gasoline blend for standard, non-flex-fuel vehicles might be E20 or E30.

Lamberty's organization has lobbied to allow the broader sale of higher ethanol blends. Station owners could use their existing infrastructure for E10 or E30 without having to make a new investment in E85 pumps. Many flex-fuel drivers, he said, might prefer a less aggressive blend than E85, and station owners would avoid a costly investment in new equipment.

Mike Rud, president of the Bismarck-based North Dakota Petroleum Marketers Association, noted the EPA's waiver for that state to sell E20 and E30 to flex-fuel owners (and others willing to try it, illegally, in their non-flex-fuel cars) and pointed out that lower blends sell "far quicker than E85."

His counterpart in South Dakota, Dawna Leitzke, executive director of the Pierre-based South Dakota Petroleum and Propane Marketers Association, said the general consensus "is that E85 is not the fuel of the future" and that lower ethanol blends give drivers "more power with a price point that is better." Drivers who use E20 and above in non-flex-fuel cars do so at their own risk and void their warranties, said Leitzke, although conversion kits (which are not approved by the EPA) exist for those who do not want to buy a flex-fuel vehicle but want to use higher blends, she said.

"E85 is probably the most inefficient (blend) of ethanol to use," added Doug Sombke, president of the Huron-based South Dakota Farmer's Union, which supports blender pumps. "E20 and E30 are both better for mileage." Shombke's own organization runs E30 in vehicles with no loss of miles per gallon, he said.

Minnesota, too, has 34 stations selling blends ranging from E20 to E50, with the highest volume concentrated in the E20 and E30 range. Groschen said that E20 and other blends offer "exciting possibilities" for extending ethanol's range beyond the two blends now most widely available and sees them as crucial as the state moves toward an E20 mandate, slated for 2013 but contingent on federal approval.

A second wind?

One of the brighter spots for E85 is support from the federal and state governments that encourage, if not require, their vehicle fleets to use the blend in flex-fuel vehicles. State governments in Minnesota and Wisconsin, in particular, have seen E85 consumption increase dramatically due to a strategy of having mobile employees use it whenever possible. More than 15 percent of North Dakota's government fleet consists of FFVs.

Tim Morse, director of the fleet and surplus services division of the Minnesota Department of Administration, said that more than 1,700 vehicles—of a total of 5,700 light trucks and automobiles—use E85 "whenever it's available" within five miles of a fill-up. From January to September of last year, 12.1 percent of the fuel consumed was E85.

"We've made a basic goal of moving away from fossil fuel dependence," he said. "When they have the opportunity, we ask employees to purchase E85 from retail vendors."

Wisconsin's fleet has roughly the same number of flex-fuel vehicles as Minnesota, and state agencies are under an executive order from the governor to reduce the use of unleaded gas by 20 percent by 2010 and 50 percent by 2015. David Jenkins, who directs market development at the Wisconsin Office of Energy Independence, said that while the drivers are buying E85, "it's only a small part of the ethanol picture" in contrast to E10's success in the state.

A few other positive—and political—signs exist on the horizon for E85. President Barack Obama was a vocal supporter of ethanol during the campaign, and his cabinet includes many politicians with ties to the ethanol industry. Detroit automakers told former President George W. Bush that 50 percent of their production would be FFVs by 2012, the kind of goal they have been known to miss in the past, but the consequences are considerably higher this time. The proposed Biofuels Security Act would offer tax credits to oil companies that add ethanol tanks to at least half of their stations and force automakers to phase out single-fuel vehicles by 2016.

The new administration leaves people like Washington, D.C.-based Renewable Fuels Association spokesman Matt Hartwig optimistic. Obama's group "shares the vision the industry has for itself" of seeing more FFVs being manufactured and a variety of ethanol blends being made available to the nation's legacy fleet of vehicles to "reduce our dependence on foreign oil."

E85 advocates concede it has been a long, arduous journey for E85 to even reach this point, much less make a real dent in the marketplace. "We're dealing with about 100 years of virtual monopoly on fuels for transportation in this country of either gasoline or diesel," according to Moffitt, of the American Lung Association of Minnesota. He and other E85 supporters say the blend was never meant to end energy dependence and clear the air on its own.

"E85 is not a complete solution; it's not a silver bullet. It's more like silver buckshot, I guess," said Moffitt. "It's one of many ways to move away slowly from our complete dependence on petroleum fuels."