Last winter ice lay thick on Mille Lacs, and walleye and perch teemed below it, ready for the taking from fishing houses set up on the surface of the giant lake in north-central Minnesota. There was plenty of snow, too, for those who like to barrel over the ice and through the woods on powerful machines. Yet it was a winter of discontent at McQuoid’s Inn, a year-round resort in Isle that rents snowmobiles and fishing houses and takes guests out on guided fishing trips.

Corporate outings, which typically generate a third of the resort's winter business, dropped by 40 percent, said owner Terry McQuoid. Companies that in past years treated their employees or clients to several days of icebound camaraderie either canceled their trips or cut back to one or two nights. In addition, fewer families and couples came north on weekends.

Corporate outings, which typically generate a third of the resort's winter business, dropped by 40 percent, said owner Terry McQuoid. Companies that in past years treated their employees or clients to several days of icebound camaraderie either canceled their trips or cut back to one or two nights. In addition, fewer families and couples came north on weekends.

To cut costs, McQuoid and his wife Lynda closed some cabins, laid off employees and tried to negotiate discounts with suppliers and utilities. In March they put their house up for sale to raise cash. “I’ve worked for myself and owned my own businesses on the lake for 35 years, and it’s definitely the toughest that I’ve ever seen,” McQuoid said. “But what I’m more worried about is where it's going to go [this] summer. How far are we from where it’s going to turn around?”

Optimism goes with the territory in the tourist trade, but a lot of other people are asking the same question this spring. Many Ninth District businesses that depend on tourism have struggled since last summer, when high gasoline prices and the global recession sapped Americans’ will to roam. In the fall the crisis on Wall Street and waves of job losses caused a sharp reduction in corporate outings, visits to tourist attractions and spending on everything from lodging to restaurant meals to souvenirs.

Travelers stayed home or dialed down their ambitions in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where many motels and bed-and-breakfasts were hard up for guests; in South Dakota, where pheasant hunting guides saw fewer customers; and in St. Paul, Minn., where some winter events scheduled for the downtown convention center were canceled.

Fewer tourists translate into less consumer spending and lower tax receipts—money that drives the economies of many communities in the district, especially during the summer. Minnesota tourism was estimated to be an $11 billion industry in 2006, supporting almost a quarter of a million jobs and generating $2 billion in government revenue. In Montana, a draw for sightseers from across the nation and around the world, catering to out-of-state visitors accounted for about 8 percent of all employment in 2005.

Some tourist areas in the district have weathered the recession fairly well so far. The Black Hills in South Dakota, for example, benefited last year from a short, intense tourist season and proximity to areas active in oil and gas drilling. In the embattled eastern part of the district, a number of tourist towns have shown surprising resilience in the face of worsening economic conditions. But the pain is widespread; since last summer year-over-year numbers for tourist visitation and spending have gone inexorably downhill in most parts of the district.

Last year tourist attractions and promotional organizations were already adapting—discounting, cutting operating costs, marketing closer to home—and those strategies are likely to be employed with even greater urgency this year. The summer, the heart of the travel season, will be a time of testing for tourist businesses and their host communities. Industry observers expect the deepest recession in decades to take a severe toll on businesses that were already struggling before the downturn.

Having a marvelous time—at home

In the summer of 2008, soaring gasoline prices were the chief concern of tourist businesses and state and local tourism officials. With the exception of western Montana, the district doesn’t attract legions of air travelers; tourist attractions and related businesses such as hotels and restaurants rely on people seeking relaxation and adventure via automobile. In July gasoline prices in many parts of the district topped $4 per gallon, prompting many travelers to curtail driving vacations and weekend getaways.

As it turned out, escalating fuel prices were only part of a growing problem for the region’s tourism industry. As the summer wore on, a deteriorating national economy compounded the effects of pump shock. As housing values dropped and 401(k) plans shriveled, more and more Americans lost their zest for travel. By October motor fuel prices had fallen, but in the wake of the banking crisis and mounting layoffs, people mostly stayed at home, saving their money and anxiously watching the gyrations of the stock market.

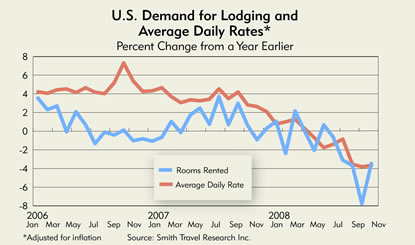

The effects of this double whammy are apparent in national travel statistics. Demand for overnight accommodation is a key gauge of tourist activity, although room demand figures include business travel. Nationwide data compiled by Smith Travel Research, a company that tracks the performance of the lodging industry, show a slight year-over-year drop in room demand over the summer, then steeper declines in the fall (see chart below). And the U.S. Travel Association estimates that domestic trips in 2008 declined about 2 percent compared with the previous year—the first drop in five years.

Tourism has also retrenched in the district. Fewer people visited national parks in the region last year; out of 14 national parks, lakeshores and national monuments in the district, 10 reported declines in visitation from 2007. Visits to other attractions such as historic sites, museums and festivals also declined in most states, as did overall demand for overnight accommodation. From May through December aggregate lodging demand in the five district states and the U.P. of Michigan fell 2 percent year-over-year, according to Smith Travel.

But this general pullback from travel hasn’t manifested itself in every district state and community to the same degree. Because of regional differences in geography and economic health, the one-two punch of high gas prices and the recession has socked some tourist destinations while dealing others only a glancing blow.

Distress signals

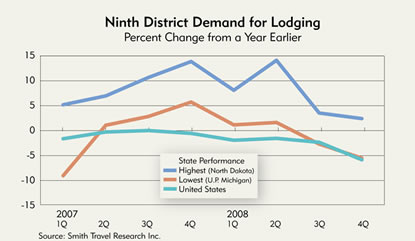

Minnesota, the U.P. and Montana appear to have suffered the most from the slowdown in leisure travel. They follow the national pattern of significant, accelerating declines in demand for lodging since last spring (see chart below). And their tourism industries show other signs—less visitor traffic, declines in tourism tax revenues, struggling businesses—of systemic stress.

Leisure travel is a discretionary expense, and slumping economies in Minnesota and the U.P.—adding insult to the injury of high summer gas prices—have constrained spending on nonessentials. Tourism in Minnesota and the U.P. relies to a considerable extent on in-state residents, so when the economy headed south in Minnesota and Michigan (unemployment has been high in both states relative to other district states since 2007), so did the fortunes of tourist attractions and businesses.

Recent figures on visitation in Minnesota and the U.P. aren’t available, but a downward trend in lodging demand is clear in the Smith Travel data. In Minnesota year-over-year demand for accommodations fell every month from May through October. Some of that drop entailed business travel, but undoubtedly leisure travelers—who drive up room demand in the summer and fall—were scaling back as well.

McQuoid can attest to that. His summer fishing and golf business was “OK,” he said, although resort guests were booking at the last minute rather than planning ahead. But in the fall bookings fell 10 percent to 15 percent compared with 2007.

At the Saint Paul Hotel in the Twin Cities, a magnet for urban tourists throughout the Upper Midwest, business started declining in the spring of last year. Occupancy and revenues at the luxury hotel had steadily increased in recent years, said General Manager David Miller. Not so last year; occupancy fell slightly below 2007 levels in the second quarter and dropped 15 percent after July, despite getting a boost from the Republican National Convention in September. Leisure bookings and corporate meeting business declined in equal measure. “We are a destination hotel, so for the most part downturns in the economy haven’t affected us much,” Miller said. “But this one has.”

The nearby Saint Paul RiverCentre convention complex has also felt the impact of the recession. Meeting and event activity began waning in December, said Ted Davis, a spokesman for the facility. Some winter events were downscaled, and others, such as a consumer boat show slated for February, were canceled.

Employment at hotels, restaurants and other leisure and hospitality businesses that depend on tourists for a good part of their livelihood declined last year in Minnesota and in the U.P. (as well as in Wisconsin, although compared to its neighbors, the state saw a less dramatic annual drop in lodging demand, partly because of a lackluster tourist season in 2007).

In Montana the dynamics of decline differ somewhat from those at work in the eastern part of the district. Although the national recession has affected the state—the unemployment rate rose to 5.4 percent in January—economic conditions in the Treasure State were rosier than in the nation as a whole last year. But unlike the district’s Great Lakes states, Montana draws about 60 percent of its visitors—most of them headed to the mountainous western third of the state—from beyond its borders.

The University of Montana estimated that nonresident visitation declined almost 4 percent last year compared to 2007—the biggest annual drop in more than a decade. Moreover, year-over-year lodging demand dipped in May and declined further for the rest of the year.

In a downturn some tourist businesses and communities buck the overarching state or regional trend. For example, ski resorts in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the U.P. reported stronger overnight bookings last winter than resorts in Colorado. “It appears that the ski season went quite well in the Upper Midwest,” said Chris Stoddard, executive director of the Midwest Ski Areas Association. He speculated that residents of the region who would typically fly out west to ski opted to hit the slopes closer to home.

Also, there’s evidence that some tourist towns in the Great Lakes states, such as Duluth, Minn., Hayward, Wis., and Sault Ste. Marie in the U.P., have so far escaped the full brunt of the recession because of their appeal as affordable driving destinations.

Going to Fargo, eh?

In contrast to Montana and the district’s eastern states, tourism in the Dakotas held its own last year as the recession deepened across the country. Lodging demand in South Dakota was steady during the peak months of July and August, and demand in North Dakota through last summer and fall actually increased over 2007. Tourist visitation and leisure and hospitality employment in the two states were sustained by a robust regional economy based on agriculture and oil and gas drilling in North Dakota, Wyoming and eastern Montana.

In Fargo, North Dakota’s largest city, evidence of slackening tourist activity was scant. All last summer and fall, the Fargo-Moorhead metro area posted impressive gains in lodging demand over 2007. Cole Carley, president of the Fargo-Moorhead Convention & Visitors Bureau, said that leisure visitors came to shop, attend athletic tournaments and take in special events such as the Red River Valley Fair. Judging by U.S. Customs Service border crossing figures and informal counts of vehicle license plates at shopping malls, many visitors were Canadians taking advantage of a weak U.S. dollar.

Reptile Gardens, a family-owned business in Rapid City, S.D., that displays rare tropical plants and reptiles, saw about 1 percent fewer visitors last year than it did the previous season. But Public Relations Director John Brockelsby isn’t complaining. “The fact that last year we were near what we did in 2007, given the gasoline prices and everything else, we look at it as a huge success,” he said. Brockelsby, who is also president of the Governor’s Tourism Advisory Board, said that the pine-clad Black Hills area benefits from its proximity to the energy-rich Williston Basin because ”typically the areas where the energy is aren’t the most scenic.” Although it’s about 300 miles south of the Canadian border, the Black Hills is also one of the closest major tourism destinations for travelers from Manitoba or Saskatchewan.

After Labor Day business dropped off at Reptile Gardens and other Black Hills attractions compared with 2007, but by then the tourist season was mostly over; three-quarters of visitors to the area come between May and September.

One area of the Dakotas that experienced a marked drop in tourist visitation and spending last year was southeastern South Dakota. In Mitchell, a popular stop for travelers headed west on Interstate 90, visitor numbers at the Corn Palace were down last summer, as was participation in the area’s fall pheasant hunt.

Discount it, and they will come

For all the variation in tourism activity across the district states, the big picture is of an industry confronting an altered economic landscape. As long as the recession lingers, states, communities and individual businesses will continue to compete for the attention of a diminished pool of travelers.

When demand for a product shrinks, the classic response is to lower its price, and many tourism operators have adopted that strategy to stay in the game. They know that economic strife has made travel consumers more price sensitive; among the businesses worst hit by the recession are those offering a high-end vacation experience, such as fly fishing guides and four-star hotels. (Smith Travel data show that luxury hotels nationwide saw sharper declines in occupancy last year than did midscale or economy hotels.)

Many tourist businesses are offering more for less. “When the economics turn against you, the only way to deal with it is to make some special deals for your customers to try to get them to keep coming back,” said William Gartner, a University of Minnesota economics professor and an authority on tourism markets.

Despite softening demand for lodging, average room rates in the district increased for most of last year, according to Smith Travel. But in the fall the resolve of hotel, motel and B&B operators began to crumble; in September average room rates in the U.P. dropped 4 percent compared to the same month in 2007, and December room rates in Minnesota and Wisconsin also fell year over year. Lodging operators in the rest of the district were still holding out at year’s end.

An e-mail survey last fall of Montana tourist operators by the University of Montana’s Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research found that many businesses were reluctant to cut prices upfront, but were open to making deals—granting discounts for extended stays, for instance, or handing out coupons good for a price break on dinner.

Last winter on Mille Lacs, McQuoid felt compelled to give a discount on accommodations or fishing house rental to anyone who demanded it. Better to land customers, he figured, than lose them to another resort down the road. “They know if we don’t do it, someone else will,” he said. Reptile Gardens stepped up its offerings of coupons and special packages last summer, and Brockelsby said he planned more of the same this season.

On the other side of the ledger, business owners have cut costs to compensate for lost revenues and gird themselves for an upcoming season that promises to punish inefficient operators. The Institute for Tourism survey found that Montana businesses were planning to lay off employees, delay capital improvements, reduce energy consumption, scale back advertising and make other cuts intended to increase the chances of survival in lean times.

Last winter Reptile Gardens established a “Go Green” committee to explore energy-saving measures such as turning off lights and turning down thermostats (although reducing heating in the reptile enclosures isn’t an option). The attraction also planned to hire 5 percent fewer seasonal workers this summer than it did last season, Brockelsby said.

In a similar bid to save on labor, the Saint Paul Hotel instituted a salary freeze last fall. And the hotel has cut some upscale services that were part of the $200-per-night package before the recession bit into profits. “It’s difficult when you run a hotel like this,” Miller said. “You have to find the line between cutting costs to save expenses and not reducing the guest experience.”

Sharpening the message

Travelers are the lifeblood of the tourism industry, and much of the responsibility for keeping it flowing falls to tourism offices, regional tourism associations, and local convention and visitor bureaus. Individual tourist operators in the district usually lack the wherewithal to mount concerted, far-reaching marketing campaigns. “We rely upon the regional marketing organizations to get people in the area,” said Brockelsby of Reptile Gardens. “Our marketing dollars are spent on getting them once they’re here.”

Taxes levied on lodging, dining and entertainment (often supplemented by state or city funding) support promotional efforts. But in areas of the district hard hit by the recession, reduced tourist spending has cut into that source of revenue. Tom Nemacheck, executive director of the Upper Peninsula Travel & Recreation Association, expects receipts from a 1 percent tax on lodging—the basis for 90 percent of the association’s annual budget—to drop over 10 percent this year. “As that continues to decline, we of course will have to do less,” he said.

Striving to make the most of limited funds, promotional organizations have shifted their focus over the past year in response to depressed travel. Highlighting customer value and timeless appeal are in. Going it alone and trying to bring the world to your door are out.

Affordability and proximity are key themes of recent marketing campaigns in the district. “Your vacation dollars go far; you don’t have to,” declare this season’s ads for U.P. tourism. Shaken by job losses and financial turmoil, people may not spend several hundred dollars on a plane ticket and luxury hotel. But they may drive to the U.P., Black Hills or North Shore of Lake Superior to stay in a modest B&B or campground.

For years the Black Hills, Badlands and Lakes Tourism Association had cast a wide net for visitors, advertising in metro areas as distant as Phoenix and Dallas. More so than other parts of the district, southwestern South Dakota has historically drawn a fair amount of fly-and-drive tourist traffic—visitors who board a plane to Rapid City, then rent a car to tour the Black Hills and Badlands. For the 2008 season, the association lowered its sights, restricting advertising to the Midwest and Great Lakes states.

“We could see from the gasoline situation and the way the national psychology was going that we better stay a little closer to home,” said President Bill Honerkamp. The association planned to stick with that approach this summer and fall.

In Duluth, which has long relied on Minnesota residents streaming north on Interstate 35 to fill its hotels, B&Bs and eateries, the watchword this season is value. Pressing home that message even more urgently than last year, the Duluth Visitors & Convention Bureau plans to promote specials offered by city hotels, motels and B&Bs in “e-blasts”—weekly e-mails to residents of the Twin Cities and other drive markets.

When the economy sours and disposable income wanes, people seek out familiar, low-risk vacation spots, said Gartner of the University of Minnesota. That presents an opportunity for tourist destinations and businesses to market aggressively to their customer base—repeat visitors and new ones predisposed to certain types of destinations. “The core customer group is the one that’s really going to carry you through this recession,” Gartner said.

Untrammeled nature has long been Montana’s biggest attraction, and the state tourism office is capitalizing on it by pursuing outdoors enthusiasts. Such visitors, dubbed “geo travelers” by Travel Montana, will make the effort to hike, kayak and camp even if financial constraints force cutbacks in other areas of their lives, said Betsy Baumgart, administrator of the Montana Promotions Division, which includes Travel Montana. Expanding on an effort begun last year, the tourism office plans “to speak to that market” with tailored marketing materials such as online hiking trail guides, Baumgart said.

Other destinations that are resolutely pursuing core customers—often with focused promotions aimed at select ZIP codes and individual households—include Minneapolis (“cultural tourists” and sports fans), Duluth (Twin Cities families) and the Black Hills (middle- class families and “soft adventurers”).

Tourism marketers in the district are also joining forces to leverage scarce marketing resources and increase their promotional reach. This summer Meet Minneapolis, the city’s convention and tourism arm, will cooperate with its counterparts in St. Paul and Bloomington on joint initiatives such as a marketing effort to attract more families to the entire Twin Cities. And the Butte (Mont.) Convention and Visitors Bureau was planning to collaborate this spring with a nearby, smaller community on a TV advertising campaign in Spokane, Wash.

Bumpy road ahead

These coping and survival strategies will be vital for tourist businesses and boosters as they gear up for the busy summer season. Tourist visitation and spending this year is likely to decline, even in parts of the district such as the Dakotas that escaped 2008 largely unscathed. Most economic forecasts call for the recession to drag on at least through the third quarter, reducing spending on travel. The U.S. Travel Association anticipates a 2 percent drop in domestic trips this year and a 3 percent falloff in travel spending.

Canadian visitors probably won’t make up for those shortfalls. Last summer Canada’s economy was relatively healthy, and its strong currency made getaways south of the border a bargain. Not so this year; the country slipped into recession at the end of 2008, and over the winter the loonie lost ground against the greenback.

Understandably, tourist businesses are nervous about what the season will bring. The University of Montana Institute for Tourism’s fall survey of tourist operators in the state found that 28 percent expected business to decline this year—the most pessimistic outlook since the survey’s inception in 1995. Many respondents said they planned to maintain their rates at 2008 levels in a bid to attract customers.

When hotels, water parks, outfitters and other tourist businesses suffer, so do their communities. Lower sales mean less money coursing through the local economy, reduced government revenues and lost jobs in towns that may offer few other employment options. (However, dependence on tourism raises questions about the costs as well as the benefits of tourism—see “A nice place to visit, but …”.)

Norma Nickerson, director of the Institute for Tourism, said via e-mail that she expects leisure and hospitality employment in Montana to decline this year as the recession tightens its grip in the state, forcing businesses that so far have held onto their workers to lay them off.

The tourism industry in the district likely won’t start growing again until regional and national economic conditions improve. Because of the importance of in-state travel in the eastern part of the district, prospects for recovery there will depend to a large degree on how quickly state economies in the region rebound. Tourist businesses in the Dakotas will keep their fingers crossed for modest increases in oil and natural gas prices to sustain incomes in the Williston Basin. In Montana and regional fly-drive markets such as the Black Hills, a key barometer will be the state of the national economy.

Brockelsby of Reptile Gardens was cautiously optimistic that the worst is already past: “Our hope for this year is to have an economy where the stock market isn’t fluctuating 10 percent in a day … to get back that consumer confidence. If we can have that by spring, that would bode well for the 2009 season.”

For some tourist operators in the district, this season may be their last. As occurred in past downturns such as the 1981–82 recession, businesses that failed to adapt to new market conditions, or were marginal before the recession, might be forced to close. “I think what you’re going to see is that some people are going to hang it up,” Gartner said.

If that happens, it will create opportunity for other enterprises—a new B&B, an expanded golf resort or gift shop—when the national economy revives. Bryan Hisel, executive director of the Mitchell Chamber of Commerce, observed that the urge to pack your bags and get out of town is powerful and cannot long be denied. “One of the things people try not to give up in their lives is recreation or adventure,” he said.

The district’s tourism industry is likely to emerge from the recession battered and financially weary, but also wiser and better equipped to compete for travelers and their dollars.