Unless you have young children, you probably don't give much thought to the child-care business. Despite the presence of a few national and regional chains, child care is mostly a cottage industry that goes about its business quietly—except when the kids play outside. The typical day care setting is an independently run neighborhood center with 20 to 30 kids, or a private home distinguishable from its neighbors only by all the playground equipment in back.

Yet child care plays a vital role in the economy, because without it many parents of infants or preschoolers would be unable to go to work. In South Dakota, four of five mothers with children under age 6 are in the labor force, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures. As a result, the licensed child-care industry in the Ninth District is quite large; a 2003 study in Minnesota estimated that child-care revenues surpassed those of clothing stores.

And, belying its soft, finger-paint-and-smiles image, child care is a tough business, closely regulated and with high costs that are difficult to cover because of the modest incomes of parents with young children. Infant care in a child-care center can cost as much as college tuition.

Parents are sensitive to increases in child-care prices, observes Tim Moore, a state economic development official in North Dakota."People will only pay so much for child care, and at some point they'll say, 'Do I pay for child care, or do I not work and stay home?'"

Like pizzerias and computer repair stores, day-care operations open and close frequently, and low average wages in the industry contribute to high staff turnover.

The past few years have been especially challenging for the industry. The Great Recession and, in some states, cutbacks in government subsidies for low-income families have made it harder for day-care providers to make it. In many district communities, child-care vacancy rates have risen, prices have faltered and more providers than usual have gone out of business.

Honey, can you drop off the kids?

Parents' economic output would be lost without someone to look after their children during the workday. Demand for child care is greater in the district than in the nation as a whole, according to the Census Bureau. Compared with the national average, district states have a high proportion of children under age 6 with parents in the workforce (see Chart 1). South Dakota leads the country in the share of children with both parents in the labor force, and Minnesota ranks second nationally in the share of children with a single working parent.

Increasingly over the past 15 years, child care has taken on another, supporting role to child minding—preparing kids to start school. Some state governments and private organizations have pushed to improve the learning environment in child-care facilities (see"Quest for quality").

The day-care industry exists to satisfy these parental and societal demands. Informal child care—children being supervised by family members, friends or neighbors—accounts for at least half of total child-care capacity in the district and nationwide. That still leaves a sizable formal, or licensed, industry—the focus of this article.

Nationally, receipts by day-care settings serving children under age 5 have been estimated at $50 billion—about one-third of 1 percent of GDP—and one in every 100 workers makes a living caring for children.

Child care has roughly the same proportional economic impact in district states, according to various studies. A 2003 analysis pegged child-care receipts in Minnesota at $1.1 billion in today's dollars—more than sales of men's and women's apparel. North Dakota day-care facilities employed 6,000 people in 2002, about the same number working as registered nurses in the state.

State regulations and average household income have a strong bearing on the type, quality and price of child care available in a particular community. So does consumer preference, notes Jamie Palagi, early-childhood services bureau chief for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services."Not all families want the same thing," she said.

Licensed child-care facilities fall into two broad classes: family child-care homes and child-care centers. Typically, operators of child-care homes care for about a dozen children in their own home. Some of the kids may be their own or the children of family members. Child-care centers generally serve a greater number of children in larger facilities and put more emphasis on school readiness (although some child-care family homes also offer such instruction).

In every district state, child-care family homes greatly outnumber centers, according to data compiled by state Child Care Resource & Referral agencies (CCR&Rs), support organizations for child-care providers and parents. For example, only about 10 percent of North Dakota's 1,370 licensed child-care facilities are centers. Centers are particularly scarce in rural areas, where population is sparse and average incomes lower than incities.

than incities.

State regulations on health and safety, frequency of inspections, provider-child ratios and required staff training differ among states. In general, centers must meet stricter standards than family child-care homes.

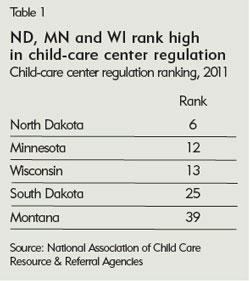

Child-care centers in North Dakota, Minnesota and Wisconsin are among the most regulated in the nation (see Table 1), and this level of oversight also extends to family child-care homes. In Minnesota any provider caring for at least two children must be licensed; in contrast, South Dakota doesn't license any of its family child-care homes.

Compared to at least some states, we start at a higher point in our licensing," said Ann McCully, executive director of the Minnesota CCR&R, a nonprofit partly funded by the state Department of Human Services (DHS).

Many helping hands

Most day-care operators don't make a lot of money; profit margins in the industry are razor thin—typically less than 1 percent. Child-care costs are high, and many parents with young children have difficulty paying for the service.

High costs stem largely from the labor intensity of child care—all the hands and minds necessary to oversee small children. Estimates of labor costs at child-care centers range from 60 percent to over 70 percent of total expenses.

State regulations mandate maximum provider-child ratios for child-care facilities. In several district states, including Montana and North Dakota, day-care providers must employ at least one child-care worker for every four infants enrolled. Higher ratios are permitted for older children—North Dakota sets a 7:1 ratio for kids aged 3 to 4 in large family child-care homes.

High staffing levels can be a matter of choice as well as legislative fiat. Some day-care operations accredited by industry associations adhere to provider-child ratios even lower than those required for licensing in most states.

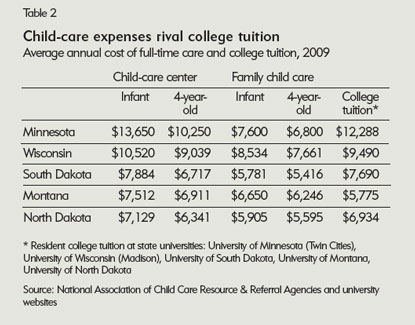

To cover worker salaries and benefits, and other expenses such as rent, food and teaching materials, child-care providers charge fees that rival tuition expenses at state universities (see Table 2). In 2009, average annual fees for infant care in a center ranged from about $7,100 in North Dakota to $13,650 in Minnesota, according to a report by the National Association of Child Care Resource & Referral Agencies.

Prices were lower on average at family child-care homes, which tend to have lower overhead expenses and a lighter regulatory burden than centers. And in both types of settings, fees for 4-year-olds are about 7 percent to 15 percent lower than for infants (preschoolers require less hands-on care).

Variances among states arise mainly from regional economic factors such as rental rates, wages and demand for child care, although regulations also influence rates. Day care is generally more expensive in cities and suburbs—where rents, wages and household incomes are higher—than in rural areas. In Minnesota, centers are concentrated in the Twin Cities metro area—which may explain the relatively high price of center care in the state.

Oh, don't forget the mortgage

Footing the bill for child care can be a problem for parents. On average, young adults—who are more likely to have preschool children—earn less than people further along in their careers, and they may have student loans to pay off.

Annual child-care fees over $10,000 can be"discouraging for a young family with both parents in their mid-20s, fresh out of college—it can be a bigger expense than your mortgage," said Chad Dunkley, CEO of New Horizon Academy, a company that operates over 40 child-care centers in Minnesota.

Low-income parents are eligible for child-care assistance subsidies provided by the federal government and matched by most states at varying levels based on average state incomes. State governments can also designate federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds to help poor families pay for child care.

A significant share of day-care revenue comes from government subsidies, although the proportion varies among states and communities. In Minnesota, child-care assistance accounted for 23 percent of average day-care center revenues in 2006, according to a financial study by the state DHS. Fourteen percent of centers derived more than half of their revenue from child-care assistance.

Yet child-care subsidy programs reach only a minority of qualified low-income families, primarily because of a lack of funds; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that in 2006, spending on child-care assistance was sufficient to cover only 17 percent of eligible families nationwide.

A number of sources said that many day-care settings, particularly those in low-income areas, are reluctant to increase fees for fear of losing customers. Hence, bottom lines get squeezed between the rock of high costs and the hard place of tight family budgets. The Minnesota DHS study found that, on average, child-care centers in the Twin Cities made a slight profit, while those outside the metro area were operating at a loss.

Nationally, and in district states, child-care workers earn much less than the average worker. In 2009, the mean annual wage for child-care workers in Montana was $16,000, according to federal labor statistics. That's about half the average annual pay for all industries in the state. Day-care workers in Wisconsin were the best paid in the district—yet earned on average less than $20,000 a year.

"As a market, as a field, we're not at the place where the profit margin will allow you to [pay a higher wage]," McCully said. Low wages contribute to high staff turnover in the industry—industry studies show that turnover rates for day-care workers range from 30 percent to 40 percent annually.

Elusive profits also contribute to a lot of turnover or churn among day-care providers themselves, although facilities come and go for other reasons—for example, mothers may open home day-care services when their own children are young and then close them when their kids reach school age. In North Dakota, 17 percent of in-home child-care programs close annually to be replaced by a similar proportion of new operations, according to the North Dakota CCR&R.

Not a kid anymore

Day-care providers may serve the young, but the industry is mature in terms of its growth. The nation and most district states (North Dakota is the exception) have seen only modest increases in child-care firms and employment over the past decade (see Charts 2 and 3). In Montana, the number of child-care facilities fell between 2001 and 2009. Child-care employment grew at a somewhat faster pace in most district states.

These data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics probably overstate growth in the child-care industry, because they count only facilities with paid employees—mostly child-care centers. Other data gathered by state CCR&Rs indicate that care provided by family child-care homes is increasing more slowly and has declined in some district states over the past 10 years.

Demographics partly explain the overall measured growth of the industry. After increasing steadily for half a century, the proportion of women in the U.S. workforce leveled off in the mid 1990s and has remained at about 60 percent.

This change, combined with lower birthrates in many states, has curbed growth in the number of children requiring formal day care. Between 2000 and 2009, the number of children with either two parents or a single parent in the labor force grew less than 1.5 percent annually in every district state except South Dakota, according to Census Bureau figures.

But the child-care industry has also felt the impact of the last recession and a decade-long decline in government subsidies for child care.

The Great Recession reduced demand for child care; parents who lost their jobs or saw their real earnings shrink withdrew their children from licensed day care or reduced their hours of care. Minnesota CCR&R data clearly show the imprint of the recession. As the unemployment rate climbed, so did the mean vacancy rate at licensed child-care facilities (see Chart 4). The downturn also affected center rates. Prices rose on average between 2003 and 2007 and then fell as the recession tightened its grip.

However, the recession barely affected the child-care industry in North Dakota, which saw continued increases in day-care numbers and child-care employment due to strong farm prices and an oil boom in the Williston Basin. State officials would like to see even faster growth in formal child care to support workforce expansion.

Many parents, including newcomers to the state who can't turn to relatives or neighbors for care, have trouble finding licensed day care, said Moore, state director of economic development for U.S. Sen. Kent Conrad. Community leaders have told Moore that "this is a problem across the state, that we're not seeing enough child-care providers and not enough high-quality child-care providers."

Reduced child-care subsidies threaten the livelihood of day-care providers in areas with a large proportion of low-income families. Even before the recession, child-care assistance payments were on the wane. After surging in the early 2000s, inflation-adjusted subsidy spending declined nationally and in every district state, according to an analysis by the Center for Law and Social Policy, a Washington, D.C.-based advocate for the poor (see Chart 5).

A number of states reduced support for social programs in response to fiscal fallout from the 2001-02 recession. In 2003, the Minnesota Legislature lowered income ceilings for child-care assistance, boosted co-pays and froze provider reimbursement rates.

Eroding subsidies combined with the recession to create a "perfect storm" for the day-care industry, McCully said. Noting that over the past eight years, the state has lost about 2,000 family child-care homes, she said that many day-care facilities in low-income areas were gradually pushed to the wall by the cutbacks.

When the going gets tough...

The financial pressures faced by parents and state governments in a still fragile economy have made a tough business even tougher. Many day care providers will continue to struggle with high operating costs and limited funding for child-care subsidies.

But child-care operators are resilient, and working parents will always need someone to tend and teach their children during the day. As the district economy recovers, demand for formal child care should increase as unemployment drops and household incomes rise.

There's anecdotal evidence that such a rebound is already under way. In the small town of Victor, Mont., a day-care operation tending about a dozen kids in a converted garage was planning to open a new facility this fall to accommodate up to 50 children.

And in Minnesota, enrollment at New Horizon day-care centers is up after dropping sharply during the recession. Last fall and winter was"one of our strongest enrollment periods in many years," Dunkley said. By March, 150 more children were enrolled in New Horizon facilities statewide than in 2007, before the recession.

—Phil Davies and Rob Grunewald