The past decade or so has been manic-depressive for ethanol producers. The fuel went from a niche market to being praised as the savior of rural America and a key to breaking the U.S. addiction to foreign oil. Then, seemingly overnight, it became reviled for its inefficiency and was blamed for higher prices at the grocery store and food riots in the developing world.

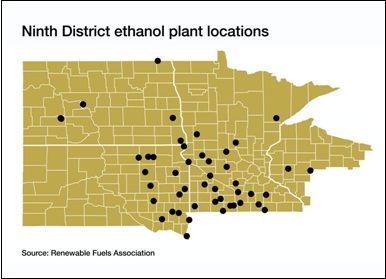

Popular or not, ethanol has become big business in the Ninth District. In addition to the many corn producers growing the primary feedstock for ethanol, the district is home to some 43 ethanol plants, mostly in Minnesota and South Dakota (see map). Together they produce almost 2.5 billion gallons a year, according to the Renewable Fuels Association.

Critics of ethanol have charged that the industry is dependent on subsidies. Meanwhile, producers and advocates have shot back that improvements in technology and increasing oil prices mean that ethanol is now competitive without subsidies. This theory is now being subjected to a real-world test.

That’s because the primary ethanol subsidy, the federal Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit, ended on Jan. 1. The credit (45 cents per gallon, most recently) went to blenders who mixed ethanol with gasoline. In addition, a 54-cent per gallon tariff on imported ethanol also expired at the end of 2011. Even though the tax credit, which had been in effect for more than 30 years, went to blenders, it had always been an indirect subsidy to ethanol distillers and feedstock farmers.

All of this has some district corn growers and distillers worried about the impact of removing subsidies. They can take heart from a pair of studies that estimate the impact will be minor. An analysis by the Center for Agricultural and Rural Development at Iowa State University focused on how much blame ethanol deserved for the surge in corn prices from 2006 to 2009. They did this by creating a model of the corn market and then running simulations in which various economic factors and policies were removed. It turned out that while ethanol was responsible for a large share of the rise in corn prices, most of that increase was due to demand-driven factors; only 8 percent of the price increase was due to direct ethanol subsidies.

A June forecast by the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri suggested that the effects of removing the blender’s credit and the tariff will be modest—a reduction of average corn prices over the next 10 years by 18 cents per bushel, less than 4 percent. An earlier analysis found that removing the tariff had a more substantial impact than removing the subsidy.

One reason the impact of removing subsidies and tariffs is less dramatic than might be expected is because there are still federal and state mandates for ethanol use. In addition, last January the Environmental Protection Agency approved a 15 percent ethanol blend (up from 10 percent) for cars made in 2001 and later. So there are other demand-drive government policies to support the ethanol market.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.