Every spring brings a certain degree of flooding somewhere in the Ninth Federal Reserve District. Floods are dramatic events, especially on a personal level. That’s why it can be easy to believe that every flood is unusual, even historic. This past summer’s floods are no exception. But not all floods are created equal. The following is a brief chronological review of some major floods that have occurred over the past 75 years in the Ninth District. Many more could be added—the Missouri, Minnesota, Mississippi and Red rivers each have their own flood histories to tell—but this review gives a sense of some of the major inundations throughout the district.

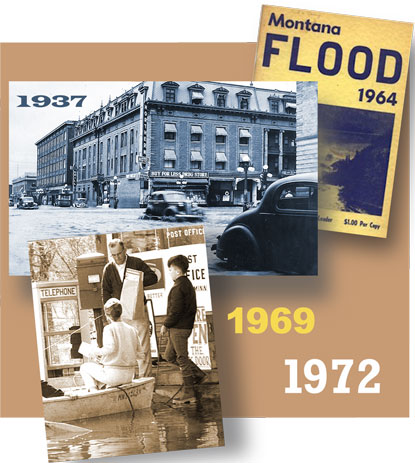

1937 – Billings, Mont.

Nearly 75 years ago, heavy rains soaked Billings and surrounding areas with four inches of rain over a 24-hour period around June 10, including nearly three inches in less than two hours. The resulting gulley gusher is still known as The Flood in local folklore. Boulders were washed onto Airport Road; Canyon and Alkali creeks—normally trickling streams—swelled into raging rivers that destroyed bridges and rail lines.

The relentless surge eventually found its way to downtown Billings and area neighborhoods. People fired shotguns to warn neighbors as water filled basements and rose to main floors in quick order. Newspaper accounts tell of people standing on porches and watching cars, trees, bicycles, steps and other detritus floating down the street. Hailstones were piled up to six feet deep from the roiling waters.

In the end, the city suffered $2 million in damages (over $31 million today), and farmers suffered $250,000 in crop damages (nearly $4 million today).

1964 – Great Falls, Kalispell and the Blackfeet Reservation, all in Montana

Known as the worst natural disaster in Montana history, the flood of 1964 was in large part the result of an unnatural catastrophe: A dam on Birch Creek collapsed following an extraordinary downpour (15 inches in 30 hours), and a wall of water up to 20 feet high roared across the Blackfeet Reservation. The home of the head-gate keeper of the irrigation system below the dam was swept away, killing 10. Eighteen were killed on the Blackfeet Reservation, and seven more downstream in the Two Medicine Area. Five other members of the Blackfeet tribe were killed, for a total of 30. Hundreds were left homeless. Damages were estimated at $55 million (about $400 million today).

1969 – Minot, N.D.

Until 2011, the spring of 1969 was remembered as the year of the worst flood in Minot’s history. Heavy snow in the Souris River Basin, along with adjoining basins, worried officials as winter pushed its way into spring. Making matters worse, there were few warm days during the winter that allowed some snowmelt to occur. A warm spell bringing temperatures in the 60s hit during the second week of April. People started to sandbag their homes, but it was too little too late; within days, hundreds of homes were abandoned as the river crested higher and higher.

Evacuation orders followed, and as the month progressed, thousands of residents left their homes. One month later, 10,000 residents were still displaced, 28 county bridges were gone, 133 culverts were washed away and 80,000 acres of good farmland were left fallow that year. Following the devastation, parts of the Souris were straightened and building restrictions established; all would be tested in later floods.

1972 – Rapid City, S.D.

This flood was not only historic for the community and state, but also for the nation in terms of lives lost—238. In addition, over 3,000 were injured and more than 100 needed hospitalization. The rain began on June 9 and continued into the following day. One Black Hills location recorded four inches of rain in 30 minutes; another area had 15 inches in six hours. All told, an average of about 10 inches fell across a 60-square-mile area.

All that water, in all those hills and valleys, meant for violent torrents. The sudden voluminous rain turned creeks like the Battle, Spring, Rapid and Boxelder into furious rivers. Losses totaled $165 million in the Black Hills (nearly $900 million today), with Rapid City suffering about 40 percent of that loss. Almost 1,400 homes were destroyed, and about 5,000 vehicles were totaled.

1993 – Mississippi River Valley

The Mississippi River drains about 40 percent of the continental United States, and when that land mass gets soaked with too much rain, the river’s many tributaries can swell and cause the Mississippi itself to top its banks. That is exactly what happened in 1993, when a largely stationary weather system continually dumped rain over the Upper Mississippi River Basin through much of the summer. At one point, over 500 river forecast stations were above flood stage simultaneously. More than 1,000 levees were topped or failed.

No state was spared, from the Great Plains of the north down to Missouri, and many cities took major hits. Economic damages were measured at $20 billion, the most destructive flood to date, with 50,000 homes damaged or destroyed. Farmland was also taken out, along with numerous transportation routes. Nearly 50 people were killed over the course of the summer.

Entire states were affected by the summer’s persistent flooding. At one point, for example, every major river in Wisconsin was over its banks, and 20 dams were overtopped, damaged or washed away. State farmers took the biggest hit, with crop and soil damage totaling $800 million ($1.2 billion today); residential losses were put at $46 million, and business losses at $31 million. Well over half of the state’s counties were declared federal disaster areas.

1997 – Grand Forks, N.D., and East Grand Forks, Minn.

Following huge winter and spring snowstorms, coupled with ice and rain as the spring progressed, the Red River was primed to serve up one of its worst floods in history. It did not disappoint. While other cities and towns, especially Fargo-Moorhead, were impacted along the way, the Red saved its accumulated worst for the cities of Grand Forks, N.D., and East Grand Forks, Minn. Flood stage on the Red at Grand Forks is 28 feet, with major flooding expected at 46 feet; the flood of 1997 topped out at over 54 feet. In April, when the great wide waters surged toward Grand Forks, the river rose by as much as one inch an hour, or two feet per day. Sandbaggers and dike builders were no match.

All of East Grand Forks’ 9,000 residents were evacuated, and 90 percent of Grand Forks’ 52,500 residents were removed as the cities suddenly found themselves immersed in a slowly moving lake-like river that spread as far as the eye could see. On the North Dakota side, 9,000 homes (83 percent) were damaged, some for good, and 751 (62 percent) commercial buildings were damaged. All downtown businesses were impacted; 11 historic buildings and 60 apartment units burned. The community had no drinkable water for over three weeks. Total damage was estimated at $3.5 billion (nearly $5 billion today).

2002 – Upper Peninsula of Michigan

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan is not known as an area prone to frequent and damaging floods, which is why the flood that occurred in 2002 in the western U.P. took many by surprise. The cause wasn’t necessarily the amount of snow—although over 100 inches of snow fell in March and April alone—it was how fast the snow melted. Two inches of rain in April followed by temperatures in the 70s and 80s opened the spigots. Residents said that they could see sheets or waves of water about a foot high moving over fields and swamping the land.

Gogebic County was the hardest hit, to the tune of $18 million, with the city of Wakefield suffering damage to 160 homes and businesses. Roads were destroyed throughout the western U.P., and some dams were compromised. Five counties in the western U.P. were eventually designated as federal disaster areas.