In recent years, India has witnessed a high rate of economic growth, which has resulted in greater personal wealth for many Indians. However, a vast section of the society is still financially excluded, meaning it does not have access to formal financial institutions. In light of recent research that shows a strong correlation between financial exclusion and poverty and inequality, the Indian government has made financial inclusion an integral part of its planning strategy. But how do you spread a banking network to a huge number of settlements at an affordable cost? In India, an effort has been made to achieve financial inclusion by using information and communication technology through a Business Correspondent model. This article provides an overview of the model and the challenges it faces.

It was Monday morning. Shankar Narayanan, 1/ a 75-year-old man who had traveled 100 miles in scorching sun to the nearest town in the district of Kerala in southern India, was waiting in a queue for his monthly pension with dozens of other elderly persons. After waiting for more than an hour, he was told that somebody had already withdrawn his pension. He had to go back empty-handed.

Until recently, this was a common scene in India. Government payments such as pensions were made in cash, which was often either siphoned off by unscrupulous agents or distributed to the wrong individual. To provide relief to people like Mr. Narayanan, the government of Andhra Pradesh, along with six banks, started a pilot project in August 2006 to make payments of government benefits to beneficiaries through smartcards that are backed by bank accounts. The main objectives of the project were (1) to increase the outreach of financial services to the poorest of the poor by using technology-based solutions, (2) to minimize the occurrence of fraudulent payments, and (3) ultimately, to achieve total financial inclusion through the use of smartcards. The distribution of payments under the pilot project started in May 2007 and was hugely successful. During August 2007, the project was reviewed and its sponsors decided to scale it up to other districts in the state. Gradually, the project graduated to a second stage, wherein banks started to provide their services at people’s doorsteps through the use of bank representatives called Business Correspondents.

The inequality-exclusion connection

Promotion of the Business Correspondent model is part of a broad financial inclusion initiative that the Indian government launched in response to increasing inequality in India. After hovering at a moderate 3.5 percent pace from the 1950s through the 1980s, India’s economic growth rate accelerated to 6.5 percent between 1990 and 2010. However, the growth has not been shared equally. Income inequality, as measured by the Gini Coefficient,2/ increased from 32.9 in 1993 to 36.2 in 20043/ (Ali and Zhuang, 2007) and much of the population of the country remains financially excluded. For example, according to 2008 data from India’s National Sample Survey Office, 45.9 million farmer households, of the total 89.3 million farmer households, did not have access to formal credit. As of June 2007, the bank-to-population ratio was a dismal 1:16,000. Out of 600,000 settlements in the country, only 30,000 had a bank branch.

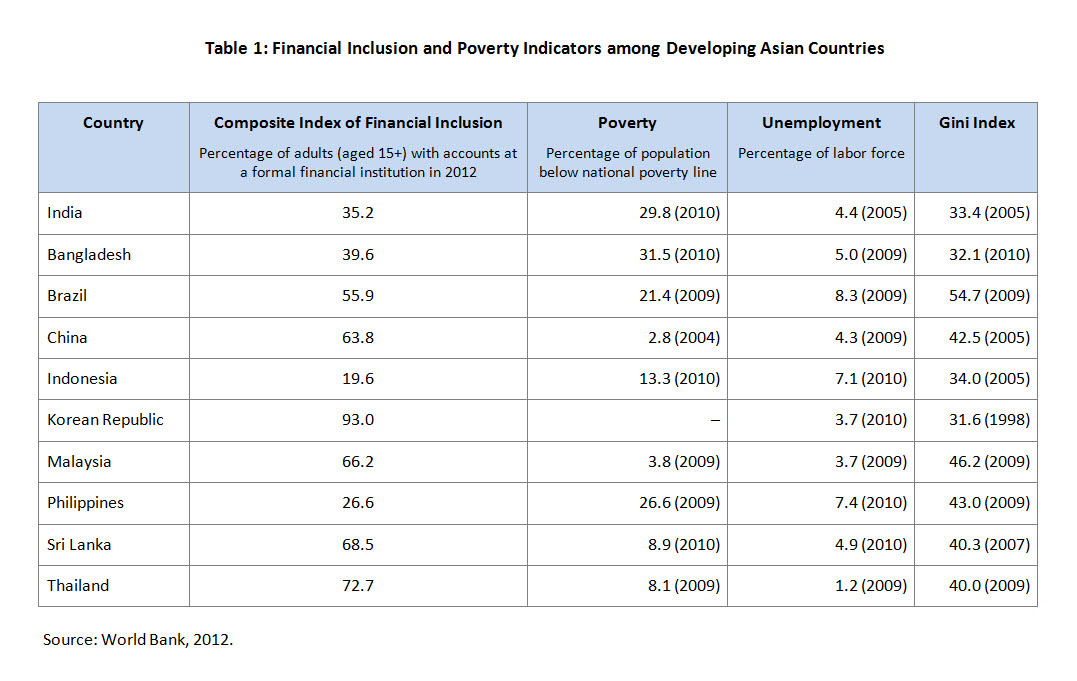

Recent studies have shown a strong link between the degree of financial exclusion and rates of poverty and inequality (see Table 1 below): the higher the financial exclusion, the higher the inequality and poverty (Thorat, 2008). Hence, in India, financial inclusion has been made an integral part of poverty alleviation strategies, and the Eleventh Five Year Plan4/ envisioned financial inclusion as a key objective. The concept of “inclusion” was defined as a process of including the excluded as agents whose participation is essential in the very design of the development process (Planning Commission, 2007).

click to view larger image

click to view larger image

Financial inclusion has both demand-side and supply-side issues. On the supply side, the banks need to reach out to a wider section of society, including the poor and vulnerable. The issue here is high cost, which can be reduced only through information and communication technology solutions. On the demand side, the major factors are low income and low asset holdings. Due to difficulties in accessing credit, poor people resort to their own personal savings to invest in health, education, or entrepreneurial activities. In emergencies, their entire savings can be eroded, leaving them vulnerable. Hence, the effort is to distribute all government social security payments through banking channels. Once people have established bank accounts, they can deposit their government payments in the bank and also pursue formal credit from the bank.

Reaching doorsteps through Business Correspondents

In January 2006, the Reserve Bank of India issued guidelines allowing banks to designate Business Correspondents (BCs) to increase their outreach. A BC is an entity that acts as a teller for the bank and carries out a full range of transactions on behalf of the bank. BCs are paid commissions by banks for the services they render. (In the same guidelines, the Reserve Bank of India also allowed banks to designate Business Facilitators, which can refer the customers’ proposals or facilitate banking transactions, but are not allowed to carry out actual transactions.) Initially, only non-governmental organizations (NGOs), micro-finance institutions, registered nonbanking financial companies, and post offices were allowed to function as BCs. However, now the guidelines have been expanded to include individuals, local grocery shops, and for-profit companies. The objective of establishing the BC role was to reach all villages with populations greater than 2,000 by March 2012, and then to reach the rest of the villages in a phased manner over three to five years.

For banks, some of the advantages of using BCs are:

- Greater reach. By using BCs, banks can reach out to areas that lack formal financial services at a much faster rate and lower cost than they can by building brick-and-mortar branches. The BC model also enables banks to offer financial services to new customers beyond their bank networks.

- Doorstep banking. The use of BCs enables banks to provide banking services, including loan disbursement and recovery, at convenient locations or even door-to-door.

- Better loan performance. Since local stakeholders like NGOs, post offices, etc., are involved in the process, they know the customers at a personal level. The personal connection enhances the customers’ accountability to the BC, which in turn improves loan performance and repayment rates.

- Quick expansion. Scaling up of the model is possible in a short span of time.

The Reserve Bank of India’s guidelines regarding BCs allow flexibility to banks regarding the use of technology for financial inclusion. This has resulted in innovations to provide inexpensive and efficient technological solutions. Today a vast array of technology, including hand-held mobile devices, Internet, and mini-ATMs and kiosks, is available. However, in India there are challenges relating to electricity and Internet connectivity in remote areas. As a result, mobile phone technology has emerged as the most effective and prevalent solution. Most of the banks use General Packet Radio Service (GPRS)5/ -enabled mobile-based online applications. Portable printing devices are synchronized with mobile handsets. Data are transferred to the bank’s intermediary server in real time. Internet security features include a default GPRS security check, an HTTPS-enabled database,6/ and log-in password security check. Each of the BC’s customers is given a biometric smartcard, which makes identification easier and more secure. With the use of mobile technology, banks can reach vast geographic areas from a remote location.

Progress and challenges

India’s financial inclusion initiative doubled its presence in 2010–2011. The number of banking outlets increased from 54,258 at the end of March 2010 to 107,604 at the end of June 2011. Of these, 22,870 are brick-and-mortar branches, while 84,274 are BC outlets. About 40 percent were added in villages with populations less than 2,000. As of June 2011, 79.1 million no-frills accounts (i.e., accounts that do not require a minimum balance) were opened by banks, compared to 49.3 million as of March 2010 (Chakrabarty, 2011).

The use of the BC model has the potential to change the lives of millions of people in the remotest parts of the country. For poor and vulnerable people, who could not think of going to the bank, banking has come to them. Increases in the number of bank accounts and the volume of loans and deposits in areas that use the BC model could indicate there is now far greater awareness of banking services. Frauds and diversions of government payments are declining as people get their social security and pension payments through bank accounts, at their doorsteps. People like Shankar Narayanan no longer need to travel 100 miles to get their pension payments. In disasters like floods and earthquakes, the government will be able to provide financial relief at a much faster rate and to the targeted people. Even in cases of medical emergencies, poor people who formerly had to take out high-interest loans from money lenders to cover doctors’ bills will now have access to credit.

The BC model is being used effectively for overall community development and social empowerment. Take the case of Sheela Gaikwad, a poor farm laborer in the Pune district in Maharashtra, who did not have enough money to even eat two times a day. With the assistance of a self-help group that was funded through transactions handled by a BC, she got a $200 loan to start her own business of selling fruit. Today, her business has expanded and she has repaid her loan. Women like Ms. Gaikwad are benefiting from credit linkages facilitated by BCs and are becoming more self-reliant. With the help of credit, today they are able to afford education for their children, which is changing their lives forever.

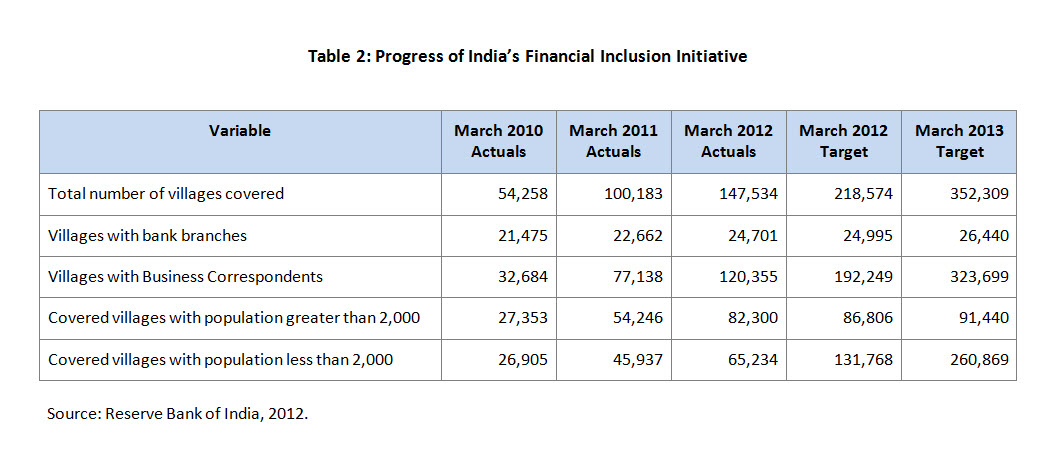

Although India’s progress on financial inclusion is considerable, it is far below the target (see Table 2). The shortfall is due to several challenges that have hindered the growth of the BC model. They include:

- Operational hurdles, such as cash handling (transporting, safekeeping, etc.), irregular accounting, frauds, and misappropriations.

- Viability issues. Despite an increasing level of awareness about the value of banking services, the majority of no-frills accounts opened by BCs are inactive. This has raised concerns that the model may not be viable. As a result, there is a shortage of funding for building the capacity of BCs. In some cases, BCs have lost money, forcing them to close. In addition, expanding into unbanked areas involves costs that banks have to absorb. If banks are not able to recover the cost for small transactions, their ability to provide credit is limited.

- Regulatory concerns. Current regulations require BCs to complete accounting and settle cash with bank branches within 24 hours of a transaction, which may not be possible due to the huge distances involved.

click to view larger image

click to view larger image

A way forward

For the BC model to succeed, the challenges described above will need to be addressed. For example, banks could finalize and standardize the technology for the BC model. Mobile technology has huge potential. However, more innovation is required in the area of security and cost reduction. New technology should be developed to allow a BC to act on behalf of multiple banks—something that might only be possible if all the banks use a single data-sharing platform.

Banks need to work out a viable business model for BCs and integrate it with their overall business policies. Only when BCs are considered a profitable business on a stand-alone basis will more money be invested in building the capacity of BCs. Also, financial inclusion must go hand-in-hand with financial education that raises awareness of the value of banking services and the possible pitfalls of unlimited credit.

Finally, all government payments, including pension and social security payments, should be compulsorily routed through banks. This would boost the volume of transactions that take place through BCs and, consequently, make the BC model more viable. One positive development in this area: The Indian government has embarked on an ambitious project of creating a unique identification number for each resident of the country. This will help banks identify their customers and thereby comply with “know your customer” regulatory requirements.

If they take steps to address the challenges that hinder the BC model, banks and the Indian government will be more likely to meet their financial inclusion targets and, ultimately, help ensure that the country’s economic growth is shared by all Indians. That includes people like Shankar Narayanan and Sheela Gaikwad, and anyone else whose circumstances have excluded them from the formal financial system.

Anupam Kishore recently served as a fellow in public policy at the Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. Under his fellowship, he had a professional affiliation with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, where he worked with the Division of Supervision, Regulation, and Credit on exploring the potential for greater collaboration between India and the U.S. in the supervision of banking and financial companies. Mr. Kishore is an alumnus of the London School of Economics and has a strong educational and professional background in fields of fiscal policy and public debt management. He has more than 16 years of experience in public service in areas of central banking, financial inclusiveness, fiscal reforms, debt management, infrastructure development, and public-private partnership models. He is also working as a consultant with the World Bank.

The views expressed in this article are Mr. Kishore’s own and not those of any organization with which he is or has been affiliated.

References:

I. Ali and J. Zhuang, Inclusive Growth Towards a Prosperous Asia: Policy Implications, Asian Development Bank, Manila, 2007.

K. C. Chakrabarty, Financial Inclusion and Banks: Issues and Perspectives, Reserve Bank of India, New Delhi, 2011.

Eleventh Five Year Plan, Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi, 2007.

Reserve Bank of India Annual Report 2011–12, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, 2012.

U. Thorat, Inclusive Growth—Role of Banks in Emerging Economies, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, 2008.

Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion, World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2012.

1/ Individuals mentioned in this article are composites intended to represent segments of the Indian population.

2/ The Gini Coefficient is a statistical measure of inequality of income or wealth. A value of 0 indicates perfect equality, while a value of 1 indicates maximum inequality.

3/ Data from the World Bank for the following year (2005) show a lower Gini coefficient of 33.4. See Table 1.

4/ The Indian economy is based in part on a series of five-year plans, which are developed, executed, and monitored by the national Planning Commission. The term of the tenth plan was completed in March 2007 and the eleventh plan is currently under way.

5/ GPRS is a cellular communications service that enhances the speed and capabilities of 2G (second generation), 3G (third generation), and W-CDMA (Wideband Code Division Multiple Access) mobile phone networks.

6/ HTTPS, or Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure, is a protocol for communicating securely over a computer network, such as the Internet.