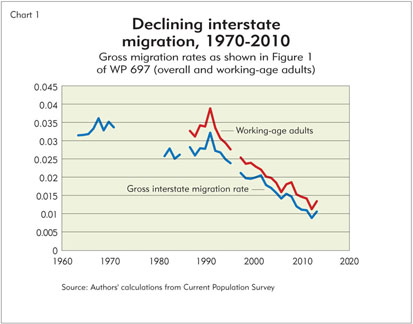

Compared with their counterparts in most other countries, American workers have long been unusually mobile, freely migrating around the country to wherever they can find good jobs. Many researchers view that high level of mobility as an important strength for the U.S. labor market: Migration allows the economy to respond flexibly to local shocks, such as the recent oil boom in North Dakota, and suggests that workers will go wherever they are most productive. But as Chart 1 shows, the rate of migration among states has been falling steadily for decades and is now about half of what it was in the early 1990s. Is the labor market losing its flexibility? And will the U.S. economy suffer as a result?

In new research (“Understanding the Long-Run Decline in Interstate Migration,” Working Paper 697), we investigate the decline in long-distance labor mobility in the United States. We show that the data rule out many popular theories—an older population with deep roots, for example, or an increase in the number of two-earner couples who won’t move unless both earners find jobs—that are linked to decreasing labor flexibility. In fact, the interstate migration rate would have fallen almost exactly as much over the past two decades if American workers’ demographics had not changed at all. In place of those theories, we offer two new explanations for the decline in U.S. migration.

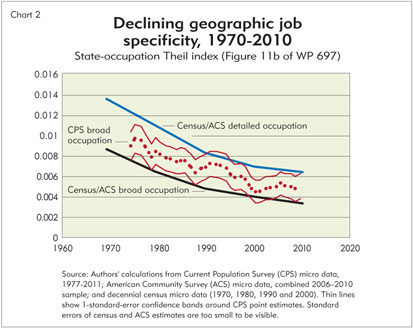

Our first explanation is that fewer workers need to move to obtain the best jobs for them, because labor markets around the country have become more similar. We show that the mix of available jobs differs less from state to state than it did 20 years ago, and the income a worker can earn in a particular occupation depends less than before on what state he or she works in. Chart 2 illustrates this decrease in the “geographic specificity of occupations” with a statistic called the Theil index. The index ranges between 0 and 1; when it is 1, each occupation is found in only one state, and when it is 0, every state has exactly the same mix of occupations. The Theil index has fallen about one-third over the past 20 years. That decrease in geographic specificity makes it easier for workers to stay where they most enjoy living and maintain their occupation.

Our second explanation for low interstate migration is that workers have better information than before about what it’s like to live in different parts of the country. Suppose you think you might want to escape Minnesota winters and move to California for the year-round sunshine. Unless you have already spent some time in California or have talked with many people who live there, you can’t be very sure you will like it—and there’s a good chance you will either miss the snow and return to Minnesota or try a third state quite soon. (Data show that someone who moves between states in one year has about a 15 percent chance of moving again the next year.)

But in recent decades, improved information technology and decreased market regulation have made it much easier to learn about far-away places without actually moving there. Airline deregulation made it cheaper to take a vacation in a place you might want to live, while telephone deregulation and the Internet help people gather information about distant states. With more information, workers are less likely to make moves they ultimately regret, and the migration rate declines.

In our research, we use a quantitative model to measure how powerful these explanations are. We find that reduced geographic specificity of occupations explains one-third of the drop in interstate migration over the past two decades. Our estimate of the effect of increased information is less precise, but it potentially explains all of the remaining drop. In other words, American workers haven’t lost their flexibility. They just don’t need to move so much anymore.