Across the country, new partnerships between community development finance and health organizations are being formed to create healthier communities. To spotlight one example from the Ninth Federal Reserve District: When Greater Minnesota Housing Fund, a community development financial institution, recently created a fund to attract socially inclined companies to invest in housing, Twin Cities-based health organization UnitedHealth Group, Inc., responded by making a $50 million investment.

“UnitedHealth Group came to the table because they understand the role that affordable housing plays in influencing health outcomes, not because we sold them on it,” says Warren Hanson, president and CEO of Greater Minnesota Housing Fund, who stresses the importance of shared goals in making the partnership between the two organizations possible. The funds are being used to develop affordable rental housing, which is health-supporting for families who may otherwise end up homeless or living in poor housing conditions.

Affordable housing is just one example of how the built environment can promote health; parks and sidewalks that support opportunities for exercise are another. Awareness of how the built environment influences individuals’ health has grown in recent years, along with awareness that communities differ in their opportunities for residents to be healthy. Less known, however, is the important role that community development financial institutions (CDFIs) often have in leveling the playing field. CDFIs are specialized entities that provide lending, investments, and other financial services in economically distressed communities. This article examines how CDFIs can shape community health and how the application of a health lens has influenced the way some CDFIs in Minnesota, the Ninth District’s most CDFI-rich state, are approaching their work. (For more general information on CDFIs, including a map showing their distribution in the Ninth District, see the article “Mass CDFI recertification push winnows list, ensures compliance” in this issue.)

An infrastructure for health

CDFIs play a critical role in addressing the social determinants of public health—which include education levels, income levels, and the characteristics of the neighborhoods in which we live, work, and play—by financing the development of infrastructure that makes good health possible. Affordable housing, community health facilities, and healthy food retail stores are some examples of health-related infrastructure improvements that CDFIs finance.

“Community development has always been in the health business, we just didn’t know it,” says Andriana Abariotes, executive director of Twin Cities LISC (Local Initiatives Support Corporation). The organization, which is a CDFI, is 1 of 31 National LISC offices across the country. The core of National LISC’s mission is to help community residents transform distressed neighborhoods into healthy and sustainable communities of choice and opportunity. While not all CDFIs explicitly mention health in their mission statements, they do emphasize the improvement of distressed communities.

“Health is a major part of improving the lives of disadvantaged people,” says Warren McLean, vice president of Community Reinvestment Fund, a Minneapolis-based CDFI that operates nationally. “Our mission focuses on improving the lives of disadvantaged people through innovative finance. And, in low-income communities with disproportionately high chronic disease rates, health is an inherent part of that mission.”

Providing the financing tools

One of the primary ways CDFIs add value to the community health sphere is by bringing innovative financing tools to the marketplace. CDFIs’ unique position in the credit market allows them to support projects that mainstream financial institutions may consider too risky to be bankable. CDFIs often provide the gap financing needed for a project, in combination with investments from government, philanthropic, or bank partners. Other times, a CDFI will act as the sole investor. Investment amounts can vary greatly depending on the type of project and the capacity of the CDFI involved; an investment in a health-supporting project in a distressed neighborhood might range from $30,000 for additions to an existing building to $30 million for the development of a large, brand-new community facility.

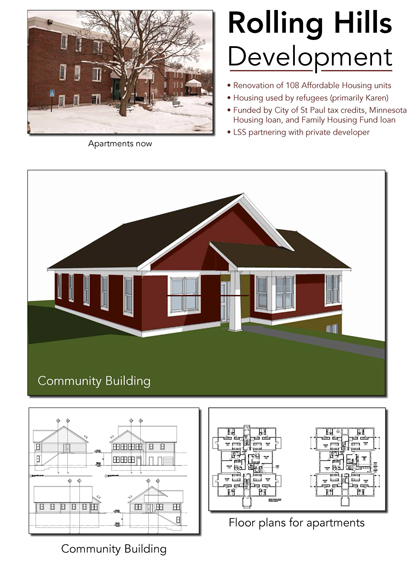

In other cases, CDFI investments may be combined with other sources to create new financing tools. One example is the Healthy Futures Fund, a national initiative to support the development of community health centers in underserved areas as well as affordable housing that incorporates health programs for low-income residents. Partners for this fund, which has supported two projects in the Twin Cities to date, include LISC, New Markets Support Company (a LISC subsidiary), Capital Link, Morgan Stanley, and the Kresge Foundation. (For more on this, see the sidebar below about Rolling Hills Apartments in St. Paul.) Another example is the Federally Qualified Health Centers Financing Fund that was launched at the Clinton Global Health Initiative in 2013. The fund, developed in response to the need for additional community health centers generated by the Affordable Care Act, is supported in part by Community Reinvestment Fund, which has also assumed a leadership role in the development of a statewide healthy food financing initiative for Minnesota. (For more on this, see the sidebar below on the Minnesota Grocery Access Task Force-Healthy Food Financing Initiative.)

Broadening participation

CDFI industry leaders note that the emphasis on community health has been beneficial for painting a more comprehensive picture of the role that CDFIs play in improving the lives of disadvantaged people and communities.

“The traditional community development conversation was one about siting, and density, and affordability requirements. Framing our work as ‘building healthy communities’ has helped us to broaden the conversation and bring more people to the table,” says Abariotes.

In addition to drawing in new partners and funders, the use of a health lens has helped to increase project engagement among community residents. Health—especially the health of children—is something people tend to be passionate about, an issue to which they can relate. According to a 2013 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Wilder Research that examined cross-sector collaboration to improve health in the U.S., community engagement is often a key element of successful projects.*/

Building capacity

The resources that CDFIs can bring to a community health initiative often extend beyond capital investments. CDFIs also frequently play an important role in capacity building through activities such as convening community stakeholders, helping to identify common goals, and evaluating the results of projects. Over the last year, Twin Cities LISC has expanded its ability to do this type of work by adding a community health advocate to its staff. The addition is part of a pilot program by National LISC that includes three additional sites: San Francisco, Indianapolis, and New York’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. Mary Wheeler, who serves as the community health advocate at the Twin Cities LISC office, has been engaged in mapping community assets and identifying the common elements among successful community development projects that have produced community health improvements. Each of the four pilot sites is tracking evidence of improved access to health care, increased access to healthy food, and increased participation in physical activity in the communities where they have invested resources. The goal is to be able to demonstrate that investments in community development strategies that support health-promoting behaviors can positively influence health outcomes for individuals, families, and communities.

“We have to do the work to be able to inform policy,” says Abariotes. “We need to be able to showcase what happened, what progress we are making, where the gaps are, and what is still missing from the equation.”

Developing cross-sector relationships

In recent years, several Federal Reserve Banks, including the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, have convened meetings of local health and community development leaders to promote awareness of shared goals and encourage collaboration across sectors. (For more on the Minneapolis Fed’s effort, see the “Minnesota Healthy Communities Initiative” sidebar below.) Such meetings have helped to lay a foundation for further collaboration between health organizations and CDFIs by fostering the development of relationships and trust, which leaders from both sectors have identified as important for advancing this work.

“You have to build trust. It can be challenging for organizations who work in the same industry to build trust, so you can imagine the difficulty when one goes outside of their sector,” says McLean.

While working across sectors to improve health can be challenging, it is clear that these joint efforts between community development finance and health organizations can yield many benefits. The Minneapolis Fed plans to continue supporting these collaborative efforts to improve the health of low- to moderate-income communities in Minnesota and throughout the Ninth District.

CDFIs + health organizations: Spotlight on collaboration

|

CDFIs + health organizations: Spotlight on collaboration

|

CDFIs + health organizations: Spotlight on collaboration

|

*/ Collaboration to Build Healthier Communities: A Report for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America, 2013.