Video Supplement: What is Farm to School?

In July 2011, on the first day of her new job, Jenny Montague embarked on a mission. As the new food service director for Kalispell Public Schools, she was now in charge of buying food and setting lunch menus for 6,000-plus students in this corner of northwestern Montana. Her goal—one she established for herself while applying for the position—was to introduce as much local, healthy, tasty food into the cafeterias as she could.

In July 2011, on the first day of her new job, Jenny Montague embarked on a mission. As the new food service director for Kalispell Public Schools, she was now in charge of buying food and setting lunch menus for 6,000-plus students in this corner of northwestern Montana. Her goal—one she established for herself while applying for the position—was to introduce as much local, healthy, tasty food into the cafeterias as she could.

She started out by giving students a small taste of things to come. Kalispell is situated roughly seven miles north of Flathead Lake in a valley that is well suited for growing a variety of fruits and vegetables, including sweet cherries that Montague suspected would be a hit with the elementary school kids. As the beginning of the school year approached, Montague contacted a local cherry growers cooperative and purchased 500 pounds of Lambert cherries, a dark-red variety known for its intense sweetness. The day before school started, when the stone fruits arrived, she and her staff got to work apportioning five cherries for every K-6 student and placing them in individual baggies. The process was time-consuming and tedious, but the payoff—jubilant, sticky-fingered kids—was well worth the effort.

“The students really enjoyed them,” she says, "and it set the tone for the entire year."

Montague is part of a nationwide wave of school food buyers who have sought to stock their school kitchens with healthy foods from local and regional farms and businesses. Called the “farm to school” movement, this effort seeks to improve student health by serving nutritious meals; educate children about nutrition, agriculture, and food systems; and support the development of local and regional economies.1/ As evidence of the relationship between healthy diets and positive social outcomes mounts, Montague and other like-minded food directors are using their purchasing power to change the relationship students and school systems have with food.

The school-health connection

The connection between children’s diets and their long-term health is well established. For instance, children who adopt poor eating habits, particularly diets that contribute to obesity, increase their risks of developing serious health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, or type 2 diabetes.2/ High-calorie, low-nutrient diets have contributed to a sharp rise in childhood obesity in recent decades. Between 1980 and 2010, the rate of obesity among children between the ages of 6 and 11 more than doubled, from 7 percent to 18 percent, while the obesity rate for adolescents between the ages of 12 and 19 more than tripled, from 5 percent to 18 percent.3/ In total, 16.9 percent of school-age kids in the U.S. were obese in 2010. 4/ Perhaps not surprisingly, only 25 percent of kids between the ages of 9 and 18 eat an average of five or more half-cup servings of produce each day. 5/

Along with home, schools serve as one of two primary eating environments for children, whose diets are heavily shaped by the foods that are available in their immediate settings. Because kids consume anywhere from one-quarter to one-half of their daily calories there, schools offer ripe opportunities to influence children’s eating habits for the better. And for many kids, school lunches may be the only daily source of fresh, nutritious food. Evidence shows that children from low-income families are less likely to have a healthful diet.6/ In Kalispell alone, 42 percent of students have family incomes low enough to qualify for the federal government’s free and reduced-price lunch program, wherein the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reimburses schools for the full or partial cost of a meal.7/

A seasonal strategy

The farm to school movement has grown rapidly over the past 15 years from a handful of programs in the late 1990s to thousands today.8/ According to the USDA, which released its first-ever Farm to School Census for the 2011–2012 school year, more than 38,000 schools, spanning all 50 states and serving a total of approximately 21 million students, purchased and served local food. 9/

In Montana, farm to school initiatives have taken root in 153 schools with a collective student body of nearly 40,000.10/ The challenge for food directors at these schools is that they have limited budgets but must create tasty, healthy lunch options that meet the serving size and nutrition requirements established by the USDA. Montague chooses to view this challenge as an opportunity: She bases her menu on food that is in season, a strategy that makes her farm to school goals both financially feasible and systemically realistic.

“You have to be creative,” she says. “There isn’t one specific way to source local foods, but it has to be a priority.”

Working within the seasonality of foods is a strategy echoed by Aubree Roth, a child nutrition education coordinator for the Montana Team Nutrition Program at the Montana Office of Public Instruction. Roth acknowledges that local foods can cost more than non-local foods, especially when purchased at a farmers market or local grocery store. But she says the large quantities that schools purchase foods in can help lower the products’ overall prices, especially when a farmer avoids the costs associated with processing and storing food for preservation and broader distribution.

“A farmer can literally drop off hundreds of pounds of produce to a school and save a lot of hassle,” Roth says, noting that produce retains its flavor and nutrients better when the time between picking the food and eating it is reduced. “Getting kids to eat healthy, tasty meals during lunch will likely positively affect the rest of their day. And they can even take those habits and food preferences home with them.”

Montague says carrots are a good example of a seasonal vegetable she buys, explaining that she purchases them from a farmers cooperative called the Western Montana Growers Cooperative. “I’ll order 400, maybe 600 pounds of carrots from them, and they’ll work with four or five different farmers to fill my order. I’ll buy them at a competitive price and they’ll be fresh.”

Finding deals during the summer, when students are on break but when some food service staff members are still working, is a particular thrill for Montague. This past summer she bought tomatoes for pizza sauce and soup, and some squash varieties for baking and as ingredients in casseroles. She also purchased 400 pounds of basil because it was in peak form and available at a reasonable cost.

“We now have a lot of pesto ranch that we can put on different meals,” she says. “We wouldn’t normally be able to afford an herb like that during the school year, but because we bought it in bulk, while it was in season, we were able to.”

Purchasing foods that are available year-round is another way to source local food. Roth notes that cattle ranches are numerous across Montana, and therefore local beef is available to many schools. As a case in point, Montague buys meat from a local cattle processor, who in turn has contracts with several nearby ranchers. Last year alone she spent more than $30,000 buying thousands of pounds of beef patties.

“And to make our meals more healthy, we’ll often mix in lentils,” she adds, noting that Montana grows more of the low-fat, high-fiber legume than any other state in the country. “We put them in casseroles, tacos, sloppy joes—anything that has ground beef. They’re a good, inexpensive filler.”

Keeping food dollars local

For Montague and other food buyers who have embraced the farm to school movement, spending money locally is the positive corollary of their purchasing decisions. Most of the food currently served in schools comes from national or regional food distributors whose suppliers vary in size and location. Farm to school purchasing involves a more direct relationship between a school and its suppliers, which are typically small operations located in or near the school’s district. By directing their food dollars to small-scale, nearby farms and processors, schools can create more market opportunities for an array of food businesses, some of which might not have contracts with the big distribution companies. Schools’ demand for local food could also foster business creation, as entrepreneurs may start food-oriented businesses that can supply the local market.

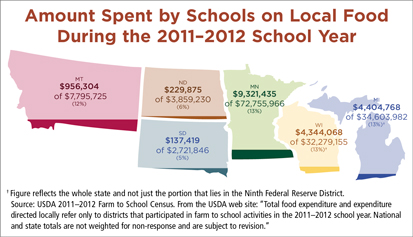

The USDA Farm to School Census estimates that nationally, schools that purchased local food spent more than $354 million on local products in the 2011–2012 school year, or nearly 14 percent of the more than $2.5 billion total they spent on food. In Montana, local food purchasing by schools that participated in the census came in at just under $1 million, or about 12 percent of the $8 million total those schools spent on food.

“These efforts have had a positive impact on the local economy by generating more revenue for local producers,” says Sadie Mele, a senior program specialist in the Child Nutrition Programs section of the USDA.

With more than 29,000 farms in Montana, 76 percent of which are owned by an individual or a family, food service directors have ample opportunities to make a local food connection.11/ Montague spends about 10 percent of her budget—around $75,000 a year—on food grown locally, which she defines as within 50 miles of Kalispell. (For more on definitions of “local,” see the sidebar below.) Another 15 percent of the budget is spent on food grown in-state but more than 50 miles away. She works with a dozen or so individual farms and with businesses and organizations that in turn work with other local producers. Montague views these connections as integral to the farm to school movement.

“When people saw the economic impact of working with local producers, the community unified behind our goals of buying and serving local foods,” she says.

The differing definitions of “local”The farm to school movement centers on local foods, but what does local mean, exactly? Turns out, there’s no one, standard definition in use among farm to school proponents. Instead, the meaning of the word varies depending on the geography and climate of a given area, as well as the seasonality of foods. For school food directors, local food can mean food grown or produced within a specific distance from a school, such as 50 miles, or it can mean food grown or produced within a specific area, such as five contiguous counties. Local can also encompass larger regions, such as an entire state or even a group of states. |

Getting kids’ hands dirty

Serving food that is largely sourced from local or regional farms is a point of pride for Patti Armbrister, the agriculture education teacher at Hinsdale Public School, a K-12 school in a rural part of northeastern Montana that has a student body of 73. Armbrister says that just about everything served in the cafeteria, particularly in the fall and spring, comes from nearby producers, but she’s most proud of the fact that some of the food served at her school traveled a mere 300 feet to reach students’ plates. The distance is short because she and her students grow the food themselves in a 12' x 18' greenhouse that’s the physical centerpiece of the school’s agriculture education curriculum. Salad greens, tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, onions—Armbrister and her students grow a bounty of produce that registers zero “food miles.”

“The students themselves built our school’s greenhouse,” she says, noting that the “outdoor classroom,” constructed in 2008, does not use electricity. “The kids are absolutely crazy about it. They love getting outside and learning about growing food.”

Armbrister explains that every student gets his or her hands dirty growing food at some point, including the kindergartners, who plant carrots from seed and then tend, harvest, and eat them.

Agriculture education—as well as food and nutrition education—is a core component of the farm to school movement. Roth, of the Montana Office of Public Instruction, notes that without understanding the connection between nutrition and food, children might not make informed, health-oriented choices as they mature and form lifelong eating habits.

“That’s why it’s important to offer food, nutrition, and agriculture education in schools,” she says, “so that students can bring this knowledge back with them to the cafeteria and to their homes.”

School gardens (or greenhouses, as in the case of Hinsdale) offer a hands-on means of teaching kids about food and agriculture. According to the USDA, 15 Montana schools had created “edible” gardens as of 2011–2012; Roth indicates the number is now much higher. Schools in Montana are also taking student field trips to farms and holding taste tests and demonstrations of locally produced foods.

To help promote farm to school, Roth organizes an annual, statewide event dubbed “Montana Crunch Time,” in which every student bites into a locally or regionally grown apple simultaneously. Much like serving local cherries to elementary school students, the apple event is a way to teach kids about the origins of a fruit that they might not have known was grown so close to their homes.

The Kalispell school district is a proud Montana Crunch Time participant. And Montague spends at least an hour every year with each 8th grade health class to explain the relationship between nutrition and healthy food choices.

“I teach them how they can vote with their forks,” she says.

At Hinsdale, students have classroom instruction in addition to hands-on greenhouse experience, to explore food-related topics more in-depth. This year, for instance, the 7th graders are conducting a class research project about mason bees, which pollinate some food crops, and will present their findings to the elementary school kids. But it’s the tactile projects—the hands-on, dirt-under-the-fingernails endeavors—that really get kids motivated.

“Next year we’re going to build a root cellar to store apples and pears,” Armbrister says. “And we’re going to eat them throughout the winter.”

A transformation, one meal at a time

More than half of the Montana school districts that bought local food in 2011–2012 plan to increase the amount of local food they purchase in the future. Montague counts herself among those numbers. In Kalispell, in just two years, she was responsible for upping the amount of local food purchased from zero to 10 percent. From her perspective, there’s little reason to believe that number couldn’t grow to 25 percent or more.

“I came into this job with a mission of transforming the food service practice at these schools into one that was based on farm to school,” she says. “And I want people to know just how easy it is.”

A corps at the core of farm to schoolThe recent growth of the farm to school movement may be partly due to the work of FoodCorps, a national nonprofit organization founded in 2009 that places young leaders in communities to help educate kids about healthy foods, build and tend school gardens, and bring local food into school cafeterias. A part of the AmeriCorps Service Network, FoodCorps currently has 125 service members placed at 108 sites in 15 states, including 10 service members in communities across Montana. For more on the organization’s work, visit www.foodcorps.org. |

For more informationResources for further reading about farm to school initiatives, such as how to start a program or how to buy local foods.

|

1/ Adapted from a fact sheet issued by the National Farm to School Network.

2/ The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Childhood Obesity Facts, available at www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/obesity/facts.htm.

3/ Ibid.

4/ Cynthia L. Ogden, Margaret D. Carroll, Brian K. Kit, and Katherine M. Flegal, “Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in Body Mass Index Among US Children and Adolescents, 1999–2010,” JAMA Vol. 307, No. 5, February 1, 2012.

5/ Mary Story, The Third School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study: Findings and Policy Implications for Improving the Health of US Children, American Dietetic Association, 2009.

6/ Ibid.

7/ According to the USDA, to be eligible for a free lunch, a child’s family income must be at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level. To be eligible for a reduced-price lunch, a child’s family income must be between 130 percent and 185 percent of the poverty level. For a family of four in the 2012–2013 school year, 130 percent of the poverty level was $29,965 and 185 percent of the poverty level was $42,643.

8/ The National Farm to School Network and the USDA.

9/ The 2011–2012 Farm to School Census, available at www.fns.usda.gov/farmtoschool/census/#. The USDA established a farm to school program in 2010 with the passage of the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, which authorizes the USDA to provide funds and technical assistance to projects that initiate or expand farm to school activities.

10/ Ibid.

11/ From the Montana findings of the USDA’s 2007 Census of Agriculture.