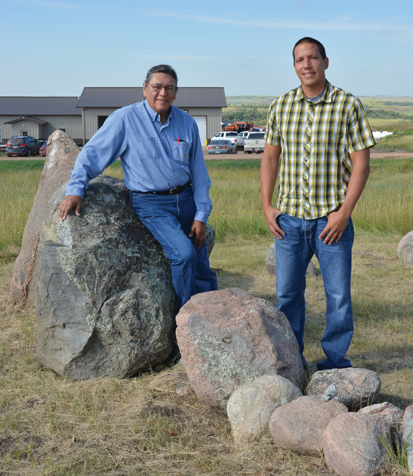

Paige and Jason Baker exemplify the economic opportunity the oil boom in western North Dakota has brought to the Three Affiliated Tribes and their homeland, the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. Father and son own Baker Consulting, a company that monitors wells, delivers supplies and performs other chores for oil and drilling firms in the Bakken oilfields. Both grew up on the reservation but moved away to pursue careers: Paige as an educator and National Park Service official, Jason as a civil engineer.

Tribal members Paige and Jason Baker own an oilfield services firm near Mandaree, N.D., on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. They built a stone medicine wheel, a Native American spiritual symbol, in a field near their business.

Photo by Phil Davies

In the late 2000s, when the oil rush came to the reservation, the Bakers came home to start an engineering firm that before long diversified into oilfield services. “When we got into oilfield services, it took off faster than we had ever planned,” Jason said.

Since then, the Bakers have invested several million dollars in their business, taking out a bank loan and drawing upon family funds to build and equip an operations facility near the small reservation community of Mandaree.

As of August, the firm employed 20 people, including seven American Indians. Hiring and retaining workers is a daily struggle in an area with low unemployment—a stark contrast to a few years ago. “We’re constantly on the lookout for new workers,” Paige said. “Everybody here who’s capable and interested in work is working, or they’re trying to get their own business going.”

Scores of other Indian-owned firms have opened their doors in the Fort Berthold area since oil drilling began in earnest six years ago. And thousands of people—both Indian and non-Indian—living on the reservation have felt the economic ripples of oil and gas development. Many tribal members have found jobs in the energy industry and in non-oil businesses, sharply raising average incomes.

“The oil boom has turned the reservation socioeconomic outlook completely around,” said Frank de la Paz, an official with a tribal department that promotes employment and business opportunities for Indians. “Poverty levels have decreased substantially; the choices for employment and the business opportunities are limitless here.” Wealth has also flowed into the reservation in the form of oil and gas royalties to leaseholders and state taxes on oil production distributed to the tribal government.

However, rapid oil development has exacted a toll on this tight-knit rural community; consequences of the boom include ravaged roads, pipeline spills, scarce housing and increased drug abuse.

The tribal government is responding to these challenges, drawing upon its oil revenues. But some tribal leaders say the tribes must do much more to reap the benefits of energy development, mitigate its costs and sustain the economic lift from the boom, even after the oil runs out.

After the flood, a “gold rush”

The Three Affiliated Tribes comprise the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara, native peoples who have endured hardship and loss for much of the past two centuries. The tribes that greeted Lewis and Clark on their journey west in 1804 were decimated by smallpox and saw their once vast lands shrink in a series of broken treaties with the U.S. government.

In the 1950s, the damming of the Missouri River to control downstream flooding inundated reservation communities and destroyed the livelihoods of many Indian farmers. In the ensuing decades, jobs were few and poverty widespread on the reservation, which covers 1,500 square miles and is home to about 6,500 people.

The fortunes of the tribes (also called the MHA Nation) improved in the early 1990s with the opening of the 4 Bears Casino on the shore of Lake Sakakawea. The casino doesn’t disclose revenues, but undoubtedly gaming income has benefited the local economy. In 2012, the casino added a 122-room hotel wing and is planning to expand its event center.

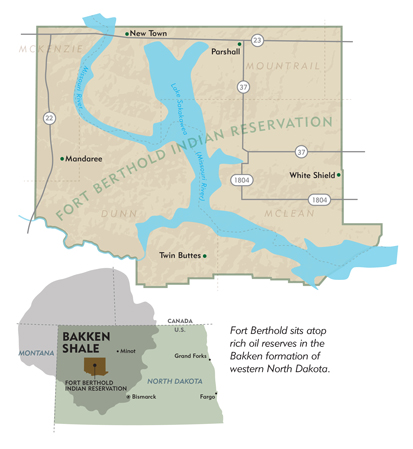

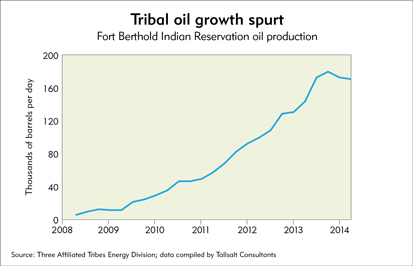

But oil and gas development has been the real game changer for the MHA Nation, broadening its economic horizons as never before. Although Fort Berthold sits in the sweet spot of the Bakken-Three Forks shale oil play, regulatory uncertainty discouraged drilling for years. After the 2008 signing of a revenue-sharing agreement between the tribes and the state, the number of active wells on the reservation quickly rose to almost 1,000. Over the past six years, oil production has surged to 170,000 barrels per day—about 15 percent of North Dakota’s output—according to the tribes’ Energy Division (see Chart 1).

If the reservation were a state, it would rank as the 10th biggest oil producer in the country, ahead of Kansas. “It’s a modern-day gold rush,” Tribal Chairman Tex Hall said in a speech at the tribes’ annual oil and gas expo at the 4 Bears Casino & Lodge in April.

Oil and associated natural gas production has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the MHA Nation government and tribal members. Over half of the wells on the reservation sit on land held in trust by the federal government for either the tribal government or individual Indian households. (The rest are situated on private property, or fee land, much of it owned by non-Indians.)

Every barrel of oil produced on the reservation yields extraction and production taxes of 11.5 percent collected by the state. Under the tax agreement with the state, the tribal government receives half of the tax revenue from production on the reservation. (Last year, a revised revenue-sharing pact increased the tribes’ share of taxes from production on fee land). State tax records show that as of July, the tribal government had received $249 million in oil tax revenue over the preceding 12 months.

The tribes also receive per-barrel royalties from oil companies for the right to pump oil from their land. In fiscal 2013, oil firms paid $99 million to the tribal government, according to figures released last year. Individual trust land residents, who enter into their own lease agreements, likely earned an even larger royalty total in 2013—at least $350 million, based on figures for previous years from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Given rising production on the reservation, royalties were probably higher for the tribal fiscal year that ended this September.

In addition to tax and lease revenue, the tribal government collects millions annually in fees paid by energy companies to do business on the reservation, including drilling, trucking and contractor licensing charges.

“Beyond our wildest dreams”

Impressive as these direct payments to the tribes are, they’re dwarfed by the overall economic impact of oil and gas development on the reservation. Billions of dollars of spending by oil companies in the Fort Berthold area has galvanized the local economy by creating jobs, increasing business income and supporting new enterprises.

The U.S. Census collects demographic data for federally recognized Indian reservations as well as for counties and communities; the most recent data are estimated averages for 2008-12. A fedgazette analysis shows that Fort Berthold leaped ahead of other Indian reservations on several socioeconomic yardsticks between 2000 and the oil boom period. By most measures, the reservation’s economic health also improved relative to the Ninth District as a whole.

Between 2000 and the boom period, the reservation’s population grew about 11 percent, a higher rate than the average for 40 other district reservations and the district overall. Both tribal members living elsewhere in the United States and non-Indians have moved to the reservation, likely attracted by job and business opportunities.

The reservation also made marked progress on other measures of economic well-being (see The Bakken effect). Labor force participation increased and unemployment dropped, in contrast to trends in the district as a whole, which were profoundly influenced by the Great Recession. Changes in workforce participation and unemployment were similar to those in oil-producing counties in the Bakken region, which have seen torrid economic growth since the mid-2000s. Annual household income on the reservation rose dramatically, and the poverty rate fell (although the most recent measure pegs the Fort Berthold poverty rate at 23 percent, almost double the districtwide rate.)

The forces behind these changes are manifest on the streets of New Town, the commercial hub of the reservation (but a civic entity separate from the MHA Nation, with its own city council and regulations). Tanker trucks stream endlessly along Main Street, oilfield workers pack the Better B Café, and two new hotels and a number of housing developments are going up in town.

A spate of construction activity combined with rising incomes in the area has spurred rapid growth at Lakeside State Bank in New Town. Over the past six years, the bank’s deposits have more than tripled while its loan portfolio has more than doubled. “Our growth has been beyond our wildest dreams,” said CEO Gary Petersen. “In the last couple of years, our lending activity has increased roughly 20 percent annually, which for a small community bank is phenomenal.” Petersen expects further growth if regulators approve a planned merger with Cornerstone Bank of Fargo.

Another sign of economic vitality on the reservation is the swelling ranks of Indian-owned businesses, particularly in oilfield services. Only a “handful” of Indian residents ran their own oilfield firms in 2008, said de la Paz, who works with Indian contractors in the Tribal Employment Rights Office. Today there are over 150, most of them owned, like Baker Consulting, by MHA Nation members. Under TERO regulations, Indian-owned firms receive preference for oilfield work on the reservation, including contracts awarded by private companies.

Tribal members have also seized opportunities in non-oil industries that are riding the oil boom. Last winter, Melanie Luger relocated her western-themed jewelry business from Mandan, N.D., to her hometown of New Town and added a women’s clothing line. Luger’s customer base has doubled since Coulee Creek Designs opened on Main Street, and she’s confident that oil development will continue to drive strong sales. “I think it’s going to be here for a while,” she said.

Down the street, Tom Hale and his wife, Jodi, put in long hours as owners of TDH Fast Foods. Sales in their restaurant have increased by half since 2008, and they’ve expanded into catering, serving up smoked brisket, steaks, burgers and other dishes at oilfield sites or venues in town. The oil boom “no doubt has impacted my livelihood,” Hale said while loading his truck for another catering run. “It’s nice to be busy instead of sitting around wondering where the next payment’s going to come from.”

"It's nice to be busy instead of sitting around wondering where the next payment's going to come from." - Tom Hale, owner of TDH Fast Foods

Photo by Phil Davies

Oil in Eden

The effects of the oil boom on the reservation have not been entirely salutary. Accelerating energy development has strained the physical and social fabric of what was until a few years ago a quiet farming community.

“Shale oil development presents both opportunities and challenges for tribes,” said Jaime Pinkham, vice president of the Bush Foundation’s Native Nations program, which has funded economic development initiatives in Indian Country. “One of the challenges is the rapid development of the resource base. How do you respond to the increased demand for infrastructure, whether it’s for homes, health care or schools?”

State highways and the thin network of tribal roads on the reservation are taking a beating from heavy oil trucks; an influx of new residents and itinerant oil workers has bid up housing prices—rents in New Town have tripled since 2009; and oil spills and pipeline breaks have increased, despoiling natural areas and threatening the water supply.

The boom has also brought social ills to the reservation. As incomes have soared, so has substance abuse with the arrival of gangs from the southwestern United States and Mexico peddling heroin and methamphetamine. According to a 2013 tribal law enforcement report, 60 percent of crimes committed on the reservation were drug-related. Increased arrests have overwhelmed the tribes’ court system and jail facilities.

The downsides of hypergrowth have similarly affected other oil patch communities, such as Williston and Watford City. But the impact is all the greater on the MHA Nation because it was even less prepared to cope with large-scale industrial development. Before the boom, the tribal administration was small because the BIA and other federal agencies had for decades assumed responsibility for managing tribal land and providing public services such as schooling and road maintenance.

In recent years, the Tribal Business Council, the elected body that sets policy on the reservation, has asserted more authority over government functions and hired more administrative workers—the tribal employee headcount has doubled to about 1,000 since 2010. But some departments still lack the staff and regulatory tools to cope with increased demand for public infrastructure and services.

“Things are growing so fast that the tribal government as a whole and its agencies are doing trial and error, trying to come up with a mode of approach where we can get a handle on things,” said Edmund Baker, director of the tribes’ environmental division.

For example, a lack of zoning in areas of the reservation beyond New Town’s jurisdiction has contributed to haphazard housing development. In some areas, houses have been built but remain unoccupied because developers are waiting for water or electricity hookups.

In Baker’s department, one person is responsible for monitoring water quality on the entire reservation. And because of scant tribal oversight of pipelines laid by oil and gas firms, environmental workers can only react to spills rather than taking steps to prevent them.

Eye on the future

However, money has the power to cure many ills. The MHA Nation has immense financial resources with which to minimize the fallout from the oil boom while maximizing its economic potential. How the tribal government spends its oil and gas income is hard to discern; the tribes’ chief financial officer declined to disclose budget details. But it’s clear that the administration is making big investments to address community needs and capitalize on energy development.

Last spring, the tribes reported to the state Legislature $71 million in spending for ongoing infrastructure development, including $24 million to reconstruct a key road artery; $30 million for housing, streets and utilities; and $6 million for sewer systems.

Providing affordable housing for tribal members is a priority for the Tribal Council. New tribal housing developments include 113 single-family homes in New Town reserved for health care and law enforcement personnel, and 30 rental units in Mandaree—a significant increase in the housing stock of the town of 600 people. The tribal government charges below-market rent for many of its apartment units and subsidizes home ownership by offering low-interest financing.

The tribes have also spent tens of millions of dollars on health care and education. In July, ground was broken on a new $14 million K-12 school in the community of White Shield.

And, with an eye to fostering more commercial development on the reservation, the tribal government has taken on the role of real estate developer. In the New Town area, a nonprofit economic development group sanctioned by the Tribal Council is moving to acquire private land and erect new buildings that would be leased to Indian entrepreneurs. Hale, vice president of the group, is involved in plans to rebuild a full block of Main Street. “What we want to do is put in a lot of unique retail stores here—hopefully, get some of our enrolled members to start their own businesses,” he said.

At the same time, the MHA Nation has launched multimillion-dollar initiatives to stake a larger claim in oil and gas production through tribally owned energy enterprises (see “Sovereignty by the barrel”).

These investments in community assets and economic development make it more likely that economic growth on the reservation will continue even after oil and gas production eventually declines. (A more explicit use of oil dollars to provide for the future is the People’s Fund, a $200 million trust created by the Tribal Council in 2010. In August, the fund paid out its first annual distribution—$500 to each adult tribal member.)

But some tribal leaders say that even greater investments—in human capital, quality of life and tribal institutions—are necessary to complete the economic transformation that the oil rush has begun. Ed Hall, a tribal elder who is Tex Hall’s uncle, worries that the tribes lack a strategic plan for sustaining prosperity and controlling their destiny: “What’s our vision? What are we going to do to preserve our reservation and exercise our sovereignty and live the way we want to?”

Hall directs MHA Nation Tomorrow, an attempt to create such a vision—a blueprint for the tribes’ economic, social and cultural development. The program has received grants from the Bush Foundation and the Northwest Area Foundation to help the tribes improve governance, seen as crucial to further reducing oversight by the federal government and effectively managing economic growth.

Recommendations that may emerge from the visioning process include enacting zoning regulations and a comprehensive tribal tax code; forming a “Human Wellness One-Stop Board” to combat alcohol and drug abuse; and establishing a tribally owned bank to facilitate business creation and expansion.

Baker, the tribes’ environmental director, would like to see more support for higher education, perhaps in the form of grants to tribal members pursuing college degrees. An ongoing need for environmental monitoring and regulation on the reservation has created career opportunities for hydrologists, geologists, petroleum engineers and other professionals.

He adds that protecting the environment is just one aspect of the monumental task the MHA Nation faces in managing the oil boom. “We’ve never seen activity like this before, as a people,” he said. “We’re going to have to think ahead.”

"What's our vision? What are we going to do to preserve our reservation and exercise our sovereignty and live the way we want to?" - Ed Hall, tribal elder and director of MHA Nation Tomorrow

Photo by Angela Eilers

Research Analyst Dulguun Batbold contributed data research to this article.

Related content

The Bakken effect

The Fort Berthold Indian Reservation has posted big gains on key measures of economic welfare