Although the overall rate of business ownership is low among the nation’s American Indians and Alaska Natives, construction firms are relatively popular business ventures for Native entrepreneurs.1/ Success in the construction business is thus significant to the American Indian business community, in general and in specific places like the Leech Lake Ojibwe reservation in northern Minnesota, where contractor and Leech Lake tribal member Irving Seelye has operated for over 20 years. But Seelye’s ability to fully capitalize on construction business opportunities has been limited by difficulties in obtaining insurance instruments known as surety bonds, to the point where he often avoids bidding on projects that require them.

Although the overall rate of business ownership is low among the nation’s American Indians and Alaska Natives, construction firms are relatively popular business ventures for Native entrepreneurs.1/ Success in the construction business is thus significant to the American Indian business community, in general and in specific places like the Leech Lake Ojibwe reservation in northern Minnesota, where contractor and Leech Lake tribal member Irving Seelye has operated for over 20 years. But Seelye’s ability to fully capitalize on construction business opportunities has been limited by difficulties in obtaining insurance instruments known as surety bonds, to the point where he often avoids bidding on projects that require them.

A surety bond is a form of insurance in which a third party (a surety company) guarantees fulfillment of a contract between a construction project owner and a contractor. That is, the surety company agrees to compensate the project owner if the contractor fails to perform as agreed. In such cases, the project owner is protected and the surety company subsequently seeks to recoup its expenses from the defaulting contractor. The contractor’s obligation to repay those expenses means that surety bonds resemble contingent lines of credit and are thus underwritten like loans. All federal construction contracts of over $150,000 require surety bonds, as do many state-, county-, and municipally-financed construction projects. Private construction projects also frequently require them.

Irving Seelye’s problems in obtaining surety bonds are not unique. Many small or new contracting firms lack the track record and financial depth to qualify for surety coverage or can only buy it at expensive rates. Contractors located or operating on American Indian reservations may face special historical and legal barriers as well.2/

Federal policymakers have not ignored the difficulties Seelye and other small or disadvantaged contractors face. Since 1971, the Small Business Administration (SBA) has operated the Surety Bond Guarantee Program (SBGP), which guarantees substantial repayment of surety bonds for qualifying small business projects. Use of the program was widespread initially but declined dramatically after the late 1970s due to a combination of factors (discussed below). However, the program recently underwent changes that may position it for wide use again, both in general and in Native communities.

Impediments in Indian Country

According to industry experts interviewed for this article, lack of experience, credit, and capital impede American Indian contractors’ access to surety bonds.3/ Experience matters for all contractors because surety companies weigh their work histories and past performance on similar projects when deciding whether to issue a bond and what to charge for it. But having prior experience with surety bonds and the financial system can be particularly helpful because it builds business relationships and teaches contractors how to navigate the bonding process. The history of limited financial services on reservations and within the American Indian community means American Indian contractors may be at a disadvantage in that regard.

As for credit and capital, having limited access to either or both can also impede access to surety bonds, even for experienced American Indian contractors. From the perspective of the bonding companies, a contractor with limited access to operating credit is more likely to have problems completing a project on time, thus raising the odds that the bonding company will have to compensate the project owner. And when the contractor lacks significant assets (capital), the bonding company is less confident that it can recoup from the contractor any compensation it may have to pay to the project owner.

Many American Indian contracting firms are small and have little capital and limited access to credit, particularly if they are located on reservations. This partly reflects a history of low incomes in reservation communities. Credit access can also be limited by lenders’ lack of certainty about or familiarity with the legal jurisdiction and process governing loans made to businesses located on reservations.4/ Capital in the form of real estate is limited on reservations by the large share of land held in trust (for the tribe or its members) by the federal government, since using trust land as collateral is often problematic. The Native American Contractors Association cites “trust-land issues, jurisdictional disputes, and cultural misunderstandings” as barriers to accessing private credit and capital on reservations. And since surety bonds resemble lines of credit, these factors can also directly limit the supply of surety bonds there.

A long, steep drop

Under the Surety Bond Guarantee Program, the SBA guarantees up to 90 percent of the surety’s loss in the event of a default.5/ In exchange, the SBA charges the contractor a percentage of the total contract value and the surety a percentage of its premium.6/ Currently, these fees are 0.72 percent and 26 percent, respectively. Peter Gibbs, deputy director of the Office of Surety Guarantees, estimates that on a typical $500,000 contract, a contractor will pay $19,000 for a performance bond guaranteed by the SBGP.

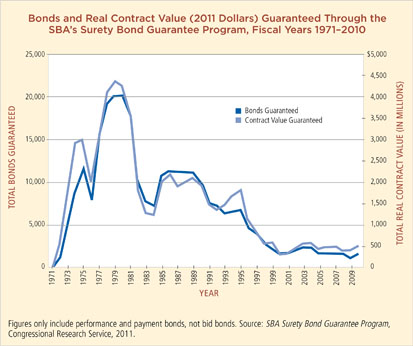

In the program’s early years, demand exceeded expectations. As shown in the graph below, participation rose dramatically throughout the 1970s, peaked in 1979, and then dropped back to low levels over the next 30 years.

Why the huge drop? A previous study indicated that burdensome paperwork required of both contractors and surety companies was a leading cause of the decline.7/ More recently, industry experts interviewed for this article identified three additional factors: program fee increases, a declining real contract value limit, and growth in the supply of non-guaranteed surety bonds designed for higher-risk contractors.

At its inception, the SBGP charged surety companies 10 percent of their premium, charged contractors 0.2 percent of the total contract value, and had a size limit of $2 million on bonds eligible for SBGP guarantees. When the fee rates proved insufficient to cover the program’s expenses, they were increased in stages to their current levels. And from 1971 to early 2013, the contract value limit stayed the same; had it been indexed to inflation, it would have been roughly $11.5 million in 2013.8/

Changes in the surety bonding industry also reduced usage of the SBGP. Surety industry participants say that the industry is more competitive today, which increases the likelihood that a contractor will find a willing bonder even without a guarantee. In addition, as noted by the Congressional Research Service, more surety companies have emerged that specialize in underwriting the higher-risk, and thus higher-priced, bonds that often would have required a guarantee a generation ago.9/ It should be noted that while the growth in this segment of the industry surely helped some American Indian contractors acquire bonds, higher premiums make it difficult for them to compete against larger, well-established firms.

When viewed together, there were two main forces that drove the decline in participation in the SBGP: changes in the surety industry made it easier for contractors to get bonds without the SBGP, albeit sometimes at a premium; and at the same time, for more and more contractors, the increasing fees and stuck-in-time bond-size limit made the SBGP an unworkable option. And as program participation flagged, awareness of the SBGP may have declined within the contracting community.

New changes, unknown effects

Recent changes to the SBGP’s bond-size limit and documentation process could make it attractive to contractors and sureties again. Most of the program’s forms can now be completed online, thus reducing the paperwork and the lag between filing and approval. And, in February of 2013, the SBA addressed the SBGP size limit, boosting it to $6.5 million generally and up to $10 million with a federal contracting officer’s approval.

Thanks to the recent changes, contractors looking for a way to access surety bonding now have an improved option. But because the changes are so new, data on whether usage of the program is up, either in general or by American Indian contractors, are not yet available. At this stage, industry experts differ in their assessments of how significant the program will become over time.

For example, one official with a surety company that specializes in the higher-risk end of the market reported that his firm’s overall usage of the SBGP was up about 30 percent in 2013 and that other firms that had previously avoided the program were becoming more interested in it. However, he had not yet seen increased usage on Indian reservations. He viewed the SBGP as helpful for American Indian contractors and speculated that its current low usage on reservations might be due to a need for more awareness of the program and its recent changes.

By contrast, other industry experts see less potential for the SBGP to increase the availability of surety bonds for American Indian contractors. The business model of some large surety companies is based on long-term relationships with well-managed, financially strong contracting firms that generally do not need guarantees to obtain low-cost bonds. Experts in this segment of the market don’t see this business model changing, even with the new SBGP features. Nor are they confident that the SBGP will significantly expand access to surety bonds on Indian reservations. From their perspective, that will only happen if real or perceived difficulties in writing and enforcing contracts with reservation-based contractors can be overcome enough so that surety companies are generally confident of the business law environment on reservations.

Only time will tell if the recent SBGP changes, a growing comfort level with tribal business law environments, or other factors will expand access to surety bonds for Irving Seelye and other American Indian contractors. Based on the range of views expressed by industry participants, the safest approach for now may be to promote both awareness of the revised SBGP and confidence in reservation legal environments.

Ahna Minge and Andrew Twite recently completed master’s degrees in public policy at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs. Minge currently serves as a health economist at the Minnesota Department of Health and Twite is a rates analyst at the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission.

1/ The most recent U.S. Census Bureau Survey of Business Owners (2007) finds that only 0.9 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives owned a business. Almost 16 percent of Native entrepreneurs were in the construction sector, making it one of the most common types of Native-owned business, and American Indians and Alaska Natives owned 1.1 percent of the nation’s construction firms.

2/ The limited availability of surety bonds for American Indian contractors was raised as a policy issue at the Growing Economies in Indian Country summit held at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington, D.C., in May, 2012. For more on the event, visit www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/conferences/growing-economies-indian-country.htm.

3/ For further details and source citations, see The Impact of Surety Bonding on American Indian and Tribally Owned Contractors, a Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Paper, available at www.minneapolisfed.org. The report also discusses tribes’ status as sovereign nations and how that affects access to surety bonds for tribally owned contracting firms. This article focuses on contracting firms owned by individual American Indians; sovereignty is not relevant to these firms.

4/ See www.minneapolisfed.org/indiancountry/#articles for a list of articles touching on these issues.

5/ The 90 percent limit applies to SBA’s Prior Approval channel, in which the SBA individually reviews each bond before guaranteeing it. Under the SBA’s Preferred channel, SBA-approved surety companies can issue guaranteed bonds without SBA review, but the guarantee is limited to 70 percent.

6/ There are three main types of surety bonds: bid bonds, which guarantee that the bidder will enter into the contract if it is awarded; payment bonds, which guarantee that all suppliers and subcontractors will be paid for their work; and performance bonds, which guarantee that the principal will perform as stated in the contract. SBGP fees only apply to performance and payment bonds. Currently, the SBA does not charge a fee to guarantee bid bonds.

7/ Sahar Angadjivand, Elyse Bailey, Jennifer Bendewald, Nicole Mickelson, Ahna Minge, Robert Pickering, and Andrew Twite, Risky Business? The Complex Case of Surety Bonding in American Indian Country, master’s thesis, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota, 2012.

8/ Calculated using the Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

9/ According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), “Specialty sureties typically required the contractor to provide collateral for the projects they bonded, and, in most cases, charged higher premiums than standard sureties.” From the CRS report SBA Surety Bond Guarantee Program, October 6, 2011.