In 2013, housing inspectors from the City of Minneapolis Department of Regulatory Services walked through nearly 1,900 one- to three-unit rental dwellings to conduct a full, 150-point safety inspection.1/ Inside each building, they moved from room to room, testing smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, checking the operability of appliances, and making sure windows weren’t painted shut. Outside, they checked the integrity of the foundation; the weather-tightness of the siding; and the condition of the chimney, roof, gutters, and downspouts. At the conclusion of each walk-through, each inspector either issued a list of repairs the building’s owner needed to make in order to bring the dwelling up to code, or gave the building the property equivalent of a clean bill of health. Anywhere from one to eight years later, this inspection process will repeat.

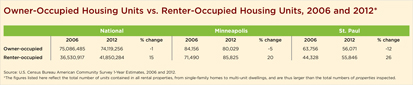

Ten years ago, the supply of single-family rental homes in Minneapolis—as well as that of two- and three-unit rental properties—might not have warranted any particular attention. But one side effect of the housing market collapse of the last decade was a surge in investors buying up foreclosed single-family homes and converting them to rental dwellings. Minneapolis housing inspectors now face the daunting task of ensuring that the fast-growing inventory of converted rental properties is made up of safe, code-compliant places to live. Just to the east of Minneapolis, St. Paul, Minn., which has also experienced a spike in rental properties,2/ confronts a similar housing-regulation scenario.

“We’re trying to find the right balance between being responsive to the concerns of both renters and landlords,” says Nuria Rivera-Vandermyde, director of regulatory services in Minneapolis. “We want to ensure healthy and safe living environments for tenants, but we also don’t want to subject the owners of the city’s rental properties to overly burdensome code-compliance orders. And we’re trying to do this in a resource environment that is pretty tight.”

Both the City of Minneapolis Department of Regulatory Services (DRS) and its City of St. Paul counterpart, the Department of Safety and Inspections (DSI), face growing rosters of rental properties as well as constrained operating budgets. In recent years, in order to allocate their limited resources effectively, both have shifted to “risk-focused” strategies whereby properties with past code-compliance problems are inspected more frequently than others. Community Dividend reached out to both departments and to individuals representing tenant and property-owner perspectives to better understand how the current regulatory procedures are working to ensure a landscape of safe, quality rental properties—a type of housing that many low- and moderate-income households in the Twin Cities call home.3/

Rentals grow, budgets stagnate, workloads increase

The constraints that the code-compliance departments in Minneapolis and St. Paul are operating under are evident in some recent numbers. Although Minneapolis has been able to grow its inspection staff by a half-dozen personnel over the past five years, from 30 in 2009 to 36 in 2014, the total number of properties the department is responsible for inspecting has risen by more than 25 percent, from 19,151 in 2009 to 24,286 in 2014.4/ That’s an increase of 36 properties per inspector. The DRS budget shrank by $2.9 million over the same time frame, from $23.5 million in 2009 down to $20.6 million in 2014. A similar situation has played out in St. Paul. The DSI, which inspects single-family homes, duplexes, and multi-unit apartment buildings, grew its residential inspection staff from 9 employees in 2007 to 14 in 2014. But the number of properties the department had to inspect grew by 62 percent, from 10,115 in 2007 to 16,391 in 2014, or an increase of 47 properties per inspector. Meanwhile, the budget for the DSI grew by a mere $500,000 over the same time frame, from $17.6 million in 2009 to $18.1 million in 2014.

Ricardo Cervantes, the director of St. Paul’s DSI, sums up his department’s situation: “We’re absolutely dealing with resource constraints.”

Using carrots and sticks

In Minneapolis, an owner of a residential dwelling with three or fewer units who wishes to let the property must first obtain a rental license, at a cost of $69 a year. If the owner of a residential dwelling that fits this classification wishes to convert the property to a rental—that is to say, the home was previously occupied by the owner—he or she must pay a $1,000 conversion fee; however, $250 of the fee will be refunded if the owner takes a city-approved property management course. All newly converted rental properties are subject to inspection by the city’s regulatory services department for compliance with a range of codes that ensure a safe living space, including codes pertaining to fire protection and structural integrity.

Prior to 2012, DRS inspected rental properties every ten years—an inflexible scheduling scheme that, according to Rivera-Vandermyde, lumped all landlords, good and bad, into one category. Under the new system the city implemented in 2012, rental properties are slotted into a three-tiered housing inspection program. Rental dwellings that complete an inspection with no or few easily fixable code violations are considered “Tier 1” properties and are scheduled for a new inspection six to eight years later. Rental dwellings with several code violations—but ones that inspectors deem fairly minor and relatively easy to fix—are considered “Tier 2” properties and are scheduled for a new inspection three to five years later, and those with many code violations and that are a “drain on public resources” are considered “Tier 3” properties and are scheduled for a new inspection annually. These are homes that have been visited multiple times throughout the year by DRS staff and police and fire departments. Currently, 66 percent of Minneapolis’s rental properties are classified as Tier 1, 30 percent are Tier 2, and 4 percent are Tier 3.

“Ultimately, we’re just enforcing the code that’s on the books,” says Rivera-Vandermyde, explaining that the department’s inspectors also make annual sweeps of different sections of the city to check on the exteriors of rental properties. “But our new system rewards the good landlords and gets tough on the bad ones.”

“We’re looking at ways we can both incentivize folks to better comply and to track those that are chronic offenders so that the ‘carrot and stick’ approach can be used to increase compliance all around,” says Rivera-Vandermyde. “We hope to be better able to use our existing resources to really home in and strategically address those that simply fail to live up to our housing standards.”

Rewarding the good, limiting the bad

While the City of St. Paul doesn’t require an official rental license, it does call on owners of one- and two-unit non-owner-occupied residences who wish to let their properties to register them with the city. At the point of registration, owners must also obtain a provisional Fire Certificate of Occupancy (FCO) through the DSI; this issuance costs $50.

According to Ricardo Cervantes, these dwellings are then required to pass a two-pronged inspection that ensures compliance with both the city’s fire safety code and its housing maintenance code.

“We’re checking over these homes to make sure they’re safe places to live,” he says. “Our primary intentions are to help ensure that people don’t lose their lives and to diminish the chances of injury.”

Once a provisional FCO is issued, the home is entered into the city’s three-tiered inspection program, which was implemented in 2007.5/ Like the system in Minneapolis, the St. Paul version bases future inspection frequency on the outcome of a home’s current inspection. Twelve months after the issuance of the provisional FCO, rental dwellings receive an initial inspection to determine whether a full FCO will be issued. They are then assigned a grade of A, B, or C, depending on whether they have few or no code infractions, moderate infractions, or a preponderance of infractions, respectively. “A” properties are scheduled for a new inspection five years later, “B” properties are inspected again after three years, and “C” properties are inspected again after one year.

To ensure that owners address code violations, the city has the power to suspend the FCO, meaning that the owners will not be able to legally let their property, or it can revoke the certificate altogether. In the worst-case scenarios, the city reserves the right to condemn a property.

“But we’re very mindful and careful about how we use that tool,” Cervantes says. “While it’s our most severe enforcement strategy, we don’t want to create more problems for tenants than necessary.”

Cervantes insists that his department is flexible with landlords if there isn’t a fire and safety issue, particularly when it comes to the duration of time it requires landlords to make repairs and who does the repair work.

“The way that we enforce our rules is reasonable,” he says. “You can often get people to do the right thing if you help them understand why it’s important. It’s about making people understand why these codes exist and how they might benefit from them.”

Tenant and landlord perspectives

Tenants, the most direct beneficiaries of rental housing standards and safety codes, can do their part by reporting problems that landlords and property managers have failed to address. The DRS and DSI take complaints about code violations from tenants and other members of the public, as do some other housing-related entities that serve the Twin Cities. According to Mike Vraa, a managing attorney at HOMELine, a tenant advocacy organization in Minnesota, the most common types of problems his organization hears about (from residents of both single-family and multi-unit rental dwellings across the state) involve appliances not working, inadequate heat, infestations (especially of bedbugs), and water damage. He indicates that more than a quarter of the repair-based calls his organization received last year mentioned the word “mold” and featured leaks and water intrusions.

However, Vraa points out that while many of these complaints may violate codes in Minneapolis and St. Paul, the state lacks a “habitability code” that explicitly spells out a lot of standards.

“So cities rely on their own codes,” he says, “and inspectors enforce these specific codes. Something that may be up to code in St. Paul might not be up to code in Minneapolis.”

While the codes themselves don’t necessarily trouble Cecil Smith, managing broker and principal with Minneapolis-based property management firm Cornerstone Property Professionals LLC, the process by which the codes are enforced and rental homes are inspected, at least in Minneapolis, gives him concern. He argues for more clarity about how and according to what criteria rental properties are assigned a tier grade. As it is now, he says, owners of rental properties only learn of their ratings by determining them from the dates on which their next inspections are scheduled.

“If it’s next year, I’m Tier 3; if it’s in six years, I’m Tier 1,” he says, adding that writing the three-tiered system into a city ordinance, rather than following it as a department policy as is currently the case in Minneapolis, would strengthen the process. “All regulation works better when it’s transparent.”

Moreover, Smith believes that the market will drive rental property owners to regulatory compliance better than any force of inspection.

“If the public knows what each rental property is graded—Tier 1, 2, or 3—then they might choose where to live based on these scores,” he says. “This would put pressure on owners of Tier 3 properties, for instance, to improve their buildings.”

This type of information may eventually be available to the public. Since her leadership of the DRS began last year, Rivera-Vandermyde has championed the release of the data that her department collects. In fact, she is working with the city’s information technology leaders to develop an “open data” portal to do just that. But in the meantime, her focus is on making Minneapolis’s residential rentals safe for habitation.

“It’s really important to me to make sure that those who take on the responsibility of leasing to others—of providing others with housing—do so responsibly and in a way that ensures safe and livable conditions overall,” she says. “We want to create environments of success.”

Top ten housing code violations in MinneapolisWhat kinds of code violations do rental housing inspectors most frequently encounter? This list from the City of Minneapolis spells them out.

|

1/ In 2013, the Department of Regulatory Services also conducted full inspections of 846 multi-unit apartment buildings with four or more dwellings, bringing the total number of buildings that received a full inspection to 2,764. That total is part of the more than 98,000 inspections of various types that the city performed on both owner-occupied and rental buildings in 2013.

2/ The City of St. Paul refers to these properties as “non-owner-occupied dwellings.” To avoid confusion throughout this article, these dwellings are called “rental” properties.

3/ According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, 40 percent of the households that rented in Minneapolis earned less than the federal poverty level over the previous 12 months; in St. Paul, the figure stood at 34 percent.

4/ One reason for the increase in properties under its purview was the department’s reabsorption of multi-unit (i.e., four or more unit) residential rental buildings, the inspections of which had been conducted by the Minneapolis Fire Department for several years.

5/ In the same year that the three-tiered inspection program was launched, Harvard University’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation recognized it with a Bright Idea award. For more information about this designation, visit www.ash.harvard.edu/Home/Programs/Innovations-in-Government/Awards/Bright-Ideas.