Newport Laboratories belongs to a new breed of employer in Worthington, a city of 13,000 in southwestern Minnesota known primarily for pork processing. Newport, a locally founded firm that was acquired in 2012 by a French animal health care firm, performs diagnostic testing and manufactures veterinary vaccines. The company, one of several animal health firms in the Worthington area, employs veterinarians, researchers, lab technicians and other professionals, many of them recent college graduates.

Newport is the type of new-economy employer that small communities everywhere covet. But companies looking to move to or expand in Worthington run into a problem: a dearth of new local housing.

“In this community, we’ve got a great school system and other amenities, but housing opportunities—whether that’s good rental opportunities, quality entry-level housing—there’s a gap there,” said Dan Greve, Newport’s business operations director. Almost all of Worthington’s housing stock is decades old; city records show that over the past five years, fewer than 30 new homes and only eight apartment units have been built in town.

“If a recruit feels they don’t have an opportunity for suitable housing, that may deter them from choosing to come to work for Newport,” Greve said.

As the regional economy continues to expand, communities across the Ninth District are seeing increased hiring. But it appears that in some nonmetropolitan areas, not enough new housing is being built for wage earners—lower-income workers such as food prep workers, nursing aides and teachers as well as professionals like those employed at Newport Labs.

As a rule, markets are efficient housing providers; when demand for shelter increases, driving up home prices and rents, builders and investors respond with sticks and bricks. But in some communities, market frictions appear to be hampering the development of workforce housing, in some cases frustrating firms’ expansion efforts and forcing workers to commute long distances from other communities with more housing choices.

Reasonably priced older housing is often available in these communities, but most units are smaller, well-worn homes unavailable for rent. Meanwhile, persistent low rents and home values have discouraged developers from building new housing in Worthington and other cities such as Roseau and Thief River Falls, Minn., Madison, S.D., and Great Falls, Mont. Rising construction costs—including the cost of complying with new building regulations—and stricter lending standards have also played a role in dampening development in the face of rising demand.

Some employers, civic leaders and policymakers see public subsidies for developers as a way to provide more housing for workers. Developers in the district have received property tax breaks and grants meant to encourage housing development, and last spring the Minnesota Legislature created a grant program to help cover the cost of workforce rental projects.

However, there’s evidence that obstacles to workforce housing development can be overcome, given time for strengthening market signals to spur builders to address gaps in local housing supply. For example, Mitchell, S.D., has seen a jump in apartment construction since a 2012 housing study showed that rising incomes would support higher rents.

Have job, will travel for housing

Since the end of the Great Recession, private industry employment has grown about 6 percent in Minnesota, South Dakota and Wisconsin combined (see July 2015 fedgazette). Job growth has occurred not just in metro areas such as the Twin Cities, Fargo-Moorhead and Sioux Falls, but also in small- to medium-sized cities in the district. From 2009 to 2014, employment in Mitchell increased 9 percent to about 13,000, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In Roseau County in northwestern Minnesota, which includes the city of Roseau, employment rose 8 percent over the same period.

Yet in some smaller communities experiencing a jobs rebound there is little housing being built for newly hired workers. Particularly scarce is new rental housing—apartments, duplexes, townhomes—suitable for lower- to middle-income workers whose paychecks won’t cover a home mortgage or higher-earning new hires who don’t want to commit to a home purchase.

New government-subsidized housing has been built in these places, but often such development is reserved at least in part for households earning 60 percent or less of median area income—too low for many wage earners.

A scarcity of new, market-rate housing in growing communities is a burden for both employers and workers. In Roseau, snowmobile and all-terrain vehicle maker Polaris Industries and other firms, many of them suppliers to Polaris, have struggled to hire and retain workers, partly because of a housing crunch.

Big fish in a small labor pool, employers such as Polaris must hire workers from outside the area, “but that’s where they run into the housing issue,” said Todd Peterson, the city’s community development director. “I can recruit people, but where do I put them when they get here? There’s not available housing for them.”

For the past two years, Polaris has leased a former group home 40 miles from Roseau to house workers from Mexico who are bused daily to its Roseau plant. Other Polaris workers recruited from elsewhere in Minnesota and other parts of the country by a temporary-labor contractor bunk in hotel rooms. The company has said that roughly half of new hires in Roseau quit within a month because they can’t find suitable permanent housing. Virtually no rental units have been developed without subsidies; and with only about a half-dozen homes being built each year, Peterson said, “we’re not putting a huge dent in the availability of housing.” Layoffs during the recession reduced housing demand, but the hiring spurt since then has renewed pressure on the housing supply.

Worthington has seen less job growth than Roseau; employment in surrounding Nobles County grew just 1 percent between 2011 and 2014, according to the BLS. But local sources said they believe that employment would be higher if more workforce housing were available in the area.

JBS USA Pork is the main employer in town with 2,200 workers involved in the slaughtering and processing of hogs into pork products. Human Resources Director Len Bakken said the company could ramp up production and hire an additional 100 to 200 workers over the next two years—if they had somewhere to live within reasonable driving distance. About 200 employees commute more than an hour each way from Sioux Falls. “That’s probably our major drawback right now,” Bakken said. “We’ve definitely got a lot more room to expand in this facility, but we don’t have enough housing to bring in more workers.”

Based on projected population and job growth, a 2013 housing study estimated local demand for approximately 500 new housing units, including at least 300 rental and senior housing units, over the next seven years. But the city has seen little of any type of residential construction in recent years. In a two-year span through 2014, city permits were issued for only six new single-family homes in Worthington. And despite vacancy rates that have hovered near zero for at least a decade, no apartments have been built in the city without subsidy since 2006.

Greve of Newport Labs said new hires often end up buying an older home—entry-level houses are available for $175,000 or less—but he believes they’d prefer to rent a new apartment or townhome with up-to-date amenities and finishes while they weigh their housing options.

Other district communities where the supply of workforce housing appears to lag demand include Thief River Falls and Perham, Minn.; Mitchell and Madison, S.D., and Great Falls, Mont. In Thief River Falls, which has seen strong job growth since the recession, electronic-component distributor Digi-Key said last year that more than 1,100 of its employees commuted from other communities in northwestern Minnesota, including some over 60 miles away.

Cheap digs, but a downside

Market circumstances have converged in these communities to prevent, or at least slow, the matching of housing supply to demand. Some of these factors have been decades in the making; others have come into play more recently.

One element stagnant housing markets have in common is persistent low rents and home values. For much of the past 50 years, economic growth has lagged in many smaller communities in the district, resulting in low rents and home appraisals relative to more populous, faster-growing areas. Low housing costs are a boon for lower-income households, but they can impede housing development because builders and investors carefully consider prevailing rents and home sales prices before deciding whether to build. Low rental rates and home appraisals reduce expected revenues and return on investment, discouraging housing development.

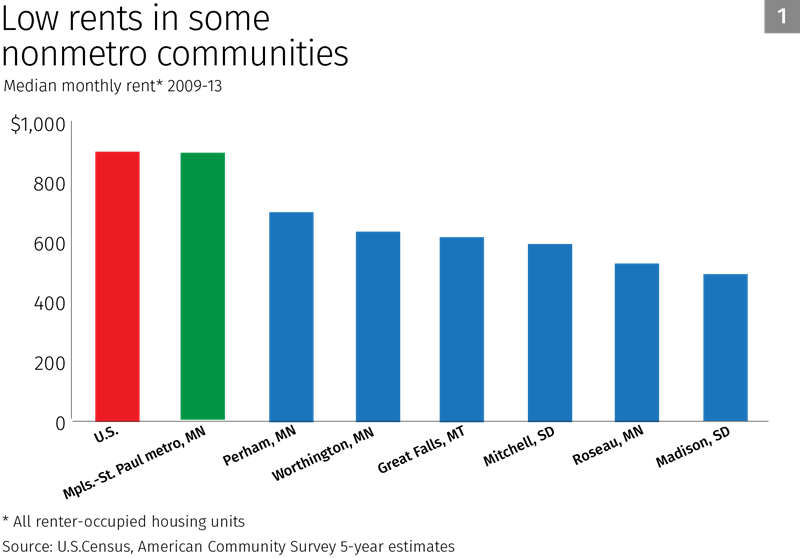

Low rents are prevalent across wide swaths of Minnesota and South Dakota. Census five-year estimates for 2009-13 show that rent levels in selected nonmetro cities with rising employment were well below the median for the Twin Cities and the country as a whole (see Chart 1). Prices of existing homes also tend to be low in low-rent markets. According to the Minnesota Association of Realtors, the 2014 median home sales price in Roseau County was $97,000—just over half of the statewide figure.

To some degree, low rents and home values are commensurate with modest local wages; Noble County’s average wage was 69 percent of the statewide average in 2014, according to the BLS. But a recent analysis by the Greater Minnesota Housing Fund (GMHF), a Twin Cities nonprofit that finances lower-income housing, indicated that rents in some northern Minnesota cities are “artificially low.”

In Roseau and Thief River Falls, for example, the study estimated that households earning the median income could afford to pay nearly twice the median market rent, based on the federal benchmark that shelter costs should not consume more than 30 percent of household income.

Why are rents persistently low in some communities with high demand for rental housing? One explanation is that these communities have two distinct, qualitatively different housing markets: existing housing and new housing. Many existing apartment units and single-family homes available for rent were built decades ago and are in need of repair and updating; they may truly not be worth more than the current rent paid. The presence of housing subsidized through federal low-income housing tax credits, USDA Rural Development loans and other government programs—and often earmarked for low-income residents—also lowers overall rents.

“It’s great to have affordable housing available,” said Amy Long, program and loan officer for GMHF, “but if that housing makes up a significant percentage of that community’s available rental, then the average rents are going to reflect that.” The Worthington housing study found that properties renting for below-market rates accounted for about 20 percent of the 1,650 occupied rental units in the city.

There’s also a market for new rental housing—energy-efficient units with modern amenities and styling—that command higher rents. As GMHF’s analysis indicated, many residents of rural communities, including in all likelihood newcomers filling openings at firms such as Polaris or Digi-Key, could afford such rents. But it appears that depressed rents for existing housing are adversely affecting the construction of new apartments and other types of rental units.

A similar dynamic has restricted the construction of new single-family housing in some communities.

Raising the roof on costs

Over the past decade, low overall rents and home values have collided with two national trends in the housing industry to further hinder the development of workforce housing in many communities: escalating construction costs and more stringent lending practices.

Rising residential construction costs have made it harder for developers to provide workforce housing at a price local markets—even segments with incomes at or above the area median—are expected to bear. Land is cheap in rural areas compared with metro areas, but prices of labor and materials in outlying areas are roughly equal to larger cities with higher rents and home sales prices.

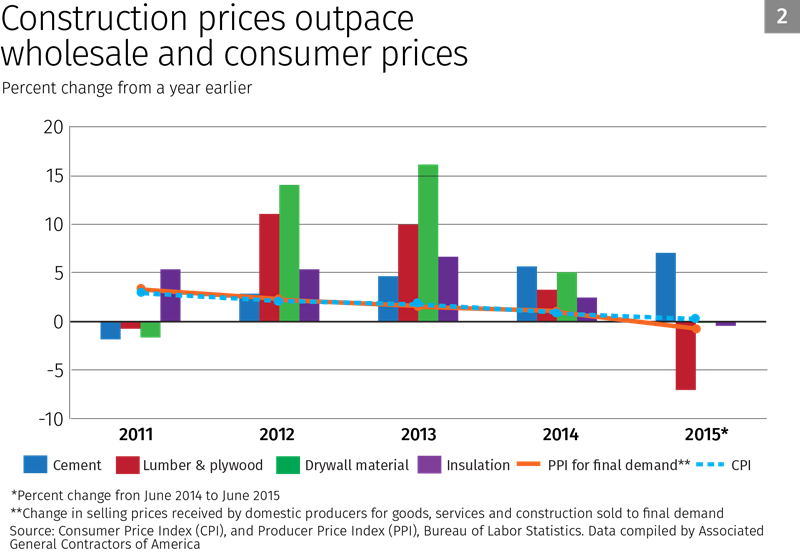

Revived demand for housing has driven up prices of construction materials nationwide; producer price indexes compiled by the BLS show that rising prices of lumber, cement, drywall and other materials have outpaced wholesale and consumer over the past five years (see Chart 2).

Scant data exist on material cost trends in the district, but multiple sources indicated that higher labor costs were driving increases in construction costs. The North Dakota oil boom has drawn construction workers from neighboring states such as Minnesota and South Dakota, although some workers have returned home since last fall’s drop in oil prices and drilling activity. Also, during the recession and slow recovery, the region’s building trades lost thousands of workers to other industries.

“Now that people want to build something, there aren’t as many skilled laborers around,” and contractors can command higher pay, said Herb Tousley, director of real estate programs in the College of Business at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. Indeed, in Minnesota wages for residential construction workers increased 11 percent from 2011 to 2014 (adjusted for inflation), according to the BLS; South Dakota housing construction workers saw a 6 percent pay hike over that period.

Several sources also cited building and land use regulation as a factor in higher construction costs. Successive revisions to state building codes have raised standards for energy efficiency and safety in residential construction; in Minnesota, for example, code changes over the past six years have mandated stronger load-bearing walls and better insulated walls and windows. Elevated costs due to new regulations are difficult to quantify, but the Builders Association of Minnesota has estimated that changes this year to state energy-efficiency codes added over $10,000 to the construction cost of an average single-family home.

Housing developers in rural areas also face financing constraints. Stung by losses during the housing crash, community banks “are being more conservative in how they’re underwriting loans,” Tousley said. Today banks pay closer attention to loan-to-value ratios than before the housing crash, often limiting loans to 60 percent to 75 percent of a project’s projected value in nonmetro areas where traditionally the limit was about 80 percent of value. Together with low housing appraisals (which reduce valuation) and high construction costs, this increases the amount of equity developers must bring to the table.

Some communities in the district, such as Roseau and Worthington, carry the additional burden of being dominated by a single employer. Both developers and bankers may think twice about building housing in such communities for fear that layoffs in an economic downturn will leave housing units empty and loans unpaid.

Stuck on the drawing board

The consequence of these market conditions for some district communities is that housing development has been slow and halting, seemingly out of step with increased demand from workers.

Multifamily rental development is the most efficient way to provide workforce housing because many units can be built on a small plot of land and the upfront costs and credit requirements for tenants are lower than for homeowners. But all too often, apartment and townhome projects never get off the drawing board because developers lack confidence in the market or have trouble securing financing.

In Worthington, hardly anyone comes to First State Bank Southwest seeking loans to build apartments, said Mark Vis, a loan officer with the bank. Last year, two local builders proposed a 24-unit apartment complex in town, Vis said. But after multiple meetings with bank and local government officials, the developers backed out of the $2 million project, citing concern that rental income wouldn’t cover the construction cost.

“The risk of building the project and trying to get a high enough rent to break even, let alone make a profit—they just couldn’t get it to pencil out,” Vis said. “They got a little gun shy, and that seems to happen a lot in Worthington.”

The few apartments and townhomes that have gone up in the city and other communities with low prevailing rents have been heavily subsidized to close the gap between anticipated rental income and construction costs.

For example, Parkland Place, a new 30-unit apartment building in Roseau, cost $3.3 million to build—$1 million more than its appraised value based on market rents. To defray construction costs, local developer Darrin Smedsmo received $460,000 from the city and a $325,000 grant from the state Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED).

A second, long-delayed apartment complex in Roseau that broke ground in July received $5.8 million in public subsidies, including $3 million in tax-exempt city revenue bonds and $634,000 in federal low-income housing tax credits. The use of the tax credits, which will be purchased by Polaris, requires 40 percent of the units to be set aside for low-income tenants.

In Madison, a city of 7,000 near Sioux Falls, $375,000 in tax increment financing sweetened the deal for the developer of 14 townhomes completed last summer. Local developer and real estate agent Brenda Thompson said the project wouldn’t have been feasible without the TIF—an arrangement in which expected property taxes from the development are used to cover infrastructure and other costs. “It was barely doable with the TIF,” Thompson said.

Another TIF-financed townhome development was built in Madison last year. “I’m not aware of any other new construction,” Thompson said. “Part of it is that rents in Madison are not high enough to justify new construction, so the TIF is necessary to help keep those rents down to a level that folks can afford,” she said.

Some market-rate single-family housing is being built in low-rent communities, but prices are beyond the means of many workers. In Roseau, the minimum price for a new single-family home is about $180,000, given construction costs and local land use and building standards. Even though average wages in Roseau County are about 85 percent of the state average, “that’s still out of reach for a lot of the folks that we see being recruited by employers, at least initially,” said Peterson, the community development director.

Similarly, in Mitchell, where average wages are lower than in Roseau, few new homes are priced below $175,000. Lot prices, infrastructure and other development costs are high in the city, said Bryan Hisel, executive director of the Mitchell Area Development Corp. At the same time, for more expensive homes, bargain prices for existing houses deter construction because costs often outstrip the house’s appraised value, limiting the amount banks are willing to lend.

“We are having a mismatch between appraisals and construction costs,” Hisel said. “The valuation of older homes is holding back the construction of new, because today’s construction costs are much higher.”

Reviving housing markets

Frictions or impediments in housing markets aren’t necessarily permanent; economic theory states that even in areas with long-standing low housing values, increased demand for homes and apartments should eventually raise prices and attract interest from builders and investors.

The case study for market adaptation in the district is western North Dakota; early in the boom, developers and lenders didn’t want to take a chance on building new housing for workers in the Bakken oilfields and oil-related industries, leery of an oil bust. In communities such as Williston and Watford City, rents skyrocketed and firms housed their workers in motels (see “No room at the inn,” April 2012 fedgazette).

But in time, confidence grew in sustained demand for housing, and houses, townhomes and apartments started going up in large quantities, although housing costs remain high in the region. “If you go up there, you see that they’re building stuff all over the place,” and construction has slackened only slightly since the drop in oil prices, Tousley noted.

Such a confidence boost was the key to a recent surge of apartment construction in Mitchell. In the wake of the recession, population growth and increased hiring by firms such as truck-trailer manufacturer Trail King Industries drove rental vacancy rates down to 1 percent, yet rents remained low and few new units were built. The development landscape changed after a 2012 housing study commissioned by the city found that local incomes had risen sufficiently to support rents that would make new apartment construction worthwhile.

“The study helped us break through the market psychology that higher rental rates were not possible to cover current construction costs,” Hisel said. Over the past two years, more than 300 apartment units have been built in the city by local developers and others, such as Stencil Homes of Sioux Falls, based elsewhere in South Dakota.

Also, in Great Falls, a 2014 market study found an “extremely tight supply” of rental housing with very low vacancy—but paradoxically modest rents. As of last summer, vacancies were still scarce in the city, but recent job growth has triggered rising rents and a spate of new apartment construction in the city.

However, policymakers in some district states are unwilling to wait for housing markets to adjust on their own. In response to the difficulties encountered by Worthington, Roseau and other communities in building workforce housing, lawmakers have enacted or proposed more public subsidies intended to overcome barriers to development.

In Minnesota, the 2015 Legislature created a $5.4 million state grant program intended to help communities outside the Twin Cities metro area develop market-rate workforce housing to support job growth. The $325,000 DEED grant for the Parkland Place apartments in Roseau came from a pilot project for this initiative, which requires a 50 percent match of nonstate funds.

This year, Montana legislators rejected a proposal for a workforce housing fund similar to North Dakota’s Housing Incentive Fund, which has spurred moderately priced housing development in the Bakken region. The bill would have awarded an income tax credit to contributors to a pool of money set aside to help pay for streets, sewer lines and other housing infrastructure.

Affordable housing organizations have also proposed leveraging public funds to jump-start stagnant housing markets. GMHF, which receives support from private foundations as well as the federal government, has launched a pilot program that would reduce the financial risks for developers of apartment projects in Minnesota. The organization would guarantee construction loans from private banks and offer additional debt financing in hopes of stimulating market-rate development that would, in time, raise prevailing rents and lead to more apartments being built.

“We believe that if there are new developments that occur in areas with demand for housing, those can help strengthen the market for future development,” said Robyn Bipes, director of programs and lending for GMHF.