The online learning model of many for-profit colleges and universities caters to working adults seeking flexible schedules as they juggle family, job and school. Knowledge leading to a college degree can be acquired as easily at the kitchen table or on the couch as in a classroom—as long as students put in the requisite effort on their preferred electronic devices.

Over the past decade, enrollment at these career colleges—many of them focused on vocational training—has increased dramatically, both nationwide and in the Ninth District. But since 2010, this trend has shifted into reverse, according to the U.S. Department of Education (DOE). Marked declines in for-profit enrollment in the United States and in the region followed heightened scrutiny of for-profit institutions, and may also have stemmed from an improved economy and increased competition from nonprofit universities and colleges.

Nationally and in district states (excluding the Upper Peninsula of Michigan), about 9 percent of students pursuing bachelor’s degrees are enrolled in institutions operated as businesses by private companies, DOE data show.

Among district states, populous Minnesota and Wisconsin have the largest concentrations of students enrolled in for-profit colleges and universities with a business presence in the district. Two of the largest district for-profits, each with over 8,000 undergraduates, are Capella University and Walden University, both based in Minneapolis. Other district for-profit colleges with undergraduate enrollments of over 1,000 include Argosy University-Twin Cities, Rasmussen College-Minnesota and National American University-Rapid City (S.D.).

Some of these institutions, such as Rasmussen College and Globe University, have physical campuses, but over 90 percent of students enrolled in for-profit colleges in district states take at least some courses online, viewing lectures and taking tests on the web.

Baccalaureate candidates at for-profit institutions are on average older than a typical college student; nationally, three of four are over 25. And in district states, two-thirds take courses part time. (In comparison, only 20 percent of district undergraduates enrolled in public or private, nonprofit institutions are part timers.)

An enrollment roller coaster

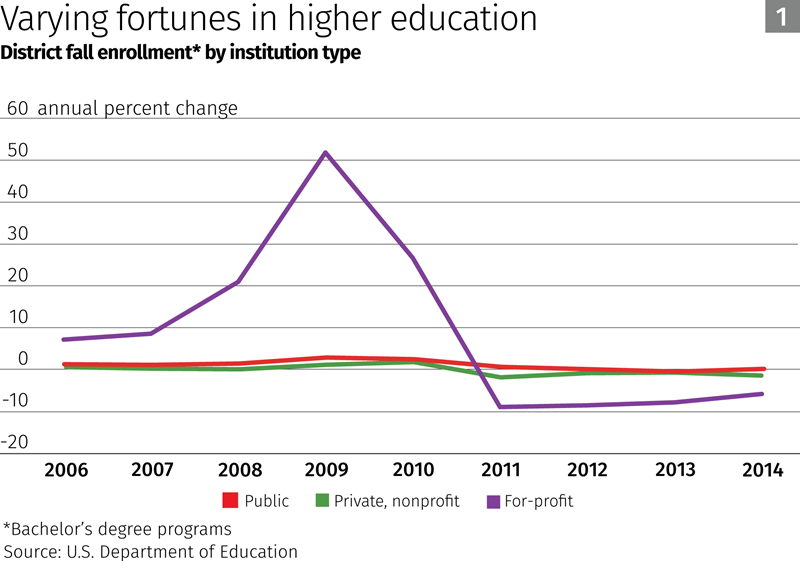

A fair wind blew through the proprietary education industry in the 2000s. In the second half of the decade, the number of students enrolled in four-year degree programs at for-profit colleges in the district almost tripled. Annual enrollment growth at career colleges far outpaced that of public and private, nonprofit colleges and universities (see Chart 1).

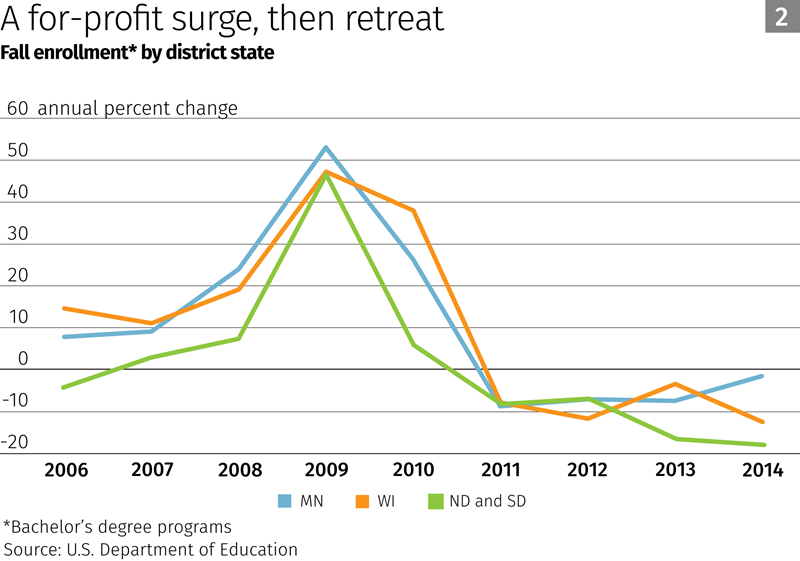

All district states saw a surge in enrollment (see Chart 2), and it’s likely that the Great Recession was a contributing factor. During the downturn, thousands of laid-off or underemployed U.S. workers went back to school to train for new careers or to enhance their skills. Rapid enrollment growth at district for-profit institutions mirrors the nationwide trend over the same period.

However, for-profit undergraduate enrollment in the district declined sharply after 2010, dropping almost 30 percent over the next four years. In contrast, four-year enrollment at public and private, nonprofit institutions fell only slightly over the same period.

Why for-profit enrollment soared, then plummeted almost as quickly, is not clear. It’s likely that several factors have affected enrollment patterns. First, increased job opportunity in a recovering economy may have reduced enrollment by unemployed adults looking to retool for new occupations.

Second, the enrollment decline at for-profit institutions coincides with a period of harsh criticism of the industry. In the late 2000s, concern about high student loan debt at for-profit colleges (in 2014, for-profit enrollees accounted for nearly half of all loan defaults, according to the DOE) and graduates’ poor career prospects led to tightened federal and state regulation of for-profits. A number of institutions across the country, including Corinthian College in California, were investigated for allegedly deceptive marketing and lending practices.

The crackdown culminated in the 2014 “gainful employment” rule, a DOE regulation that requires vocational programs at for-profit institutions and community colleges to meet minimum thresholds for the annual income-to-debt ratios of their graduates. Media coverage of these regulatory actions may have led some students to avoid for-profit colleges and enroll elsewhere.

Finally, competition from nonprofit schools may have eroded for-profit enrollment. Public universities and community colleges, which often charge lower tuition because they’re supported by state or local taxes, have increased their online course offerings to appeal to the same working adults served by for-profit institutions. In 2014, almost all public institutions in the district offered some form of distance learning, according to DOE. And the share of private, nonprofit colleges with online study options increased 10 percentage points between 2012 and 2014, to 69 percent.

Sliding graduation rates

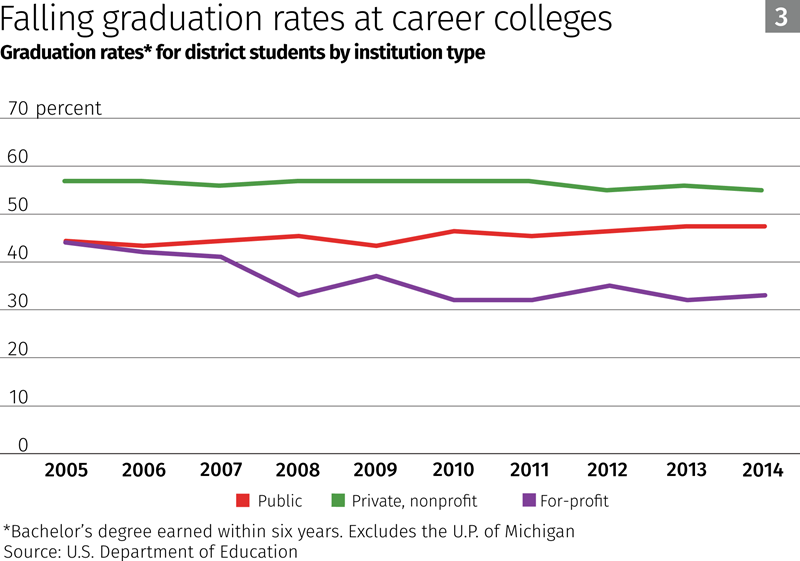

For-profit institutions have also drawn rebuke for their low graduation rates. The average rate for district students seeking bachelor’s degrees at career colleges has declined over the past decade (Chart 3). The share of students earning diplomas from for-profit colleges within six years fell 11 percentage points from 2005 to 2014.

Nonprofit institutions haven’t experienced a similar drop, and since 2009 the average graduation rate of students at public colleges and universities in district states has inched up, while the for-profit rate has stayed mostly flat. National graduation rates for the three types of institutions closely track the district pattern.

As with enrollment declines at for-profit institutions, the reason for slumping graduation rates isn’t clear. Regulatory scrutiny of the industry probably has played a role. Negative press coverage since 2007 may have induced the most capable students to vote with their feet, eroding the academic skills of the for-profit student body.