On a sunny afternoon in St. Paul, Minn., a driver sits waiting in traffic along a stretch of University Avenue. Commercial and residential buildings line the far side of the street and a fenced-off parking lot sits to the right. The setting, nondescript, looks uninspiring. The driver understandably notices little of her surroundings. Instead, she is waiting for the other vehicles to inch forward so she can crawl along, too. University Avenue is undergoing a major reconstruction and traffic seems to move at a glacial pace.

But something in her periphery catches her attention. As she advances a few car lengths, she sees a splash of vibrant hues—turquoise, orange, yellow—twinkling from the chainlink fence. With cement, asphalt, and brick surrounding her in all directions, the kaleidoscope of color draws her eyes.

What she sees is an arresting mosaic of stained glass installed in the diamonds of the chainlink. The contrast of delicate beauty against the drabness of the metal fence is striking, made doubly so by the sunlight streaming through the glass and spreading the pattern onto the sidewalk.

Laura Zabel, executive director of St. Paul-based Springboard for the Arts, said she had multiple friends texting and calling her to describe this scene. After all, her organization, which promotes community and economic development through arts-based programming, made the grant to the neighborhood artist who installed the stained glass.

“When you see an installation like this, stained glass painstakingly placed in a fence, how does it make you feel about your neighborhood?” she reflected. “Does it give you a sense that you could change something about your surroundings, too? Does it make you rethink how you feel about those parts—like that stretch of University Avenue—that are seemingly unloved?”

The stained glass installation is an example of creative placemaking, defined as the use of arts or expression in some form to advance community and economic development for a specific geographic area, such as a city neighborhood. Creative placemaking can include enhancing neighborhood vibrancy and social networks; advancing resident equity, including racial equity; fostering neighborhood identity; and strengthening community and business vitality.

“The arts can change people’s relationship to places,” said Zabel. “When residents see their own agency in a place—their own power to change their neighborhood for the better—it has a tremendous ripple effect in terms of people’s investment in their communities.”

Changing the narrative with “big black dogs”

Between 2010 and 2014, stretches of University Avenue in St. Paul underwent periods of heavy construction as a new passenger light-rail transit (LRT) line was installed to connect the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Projected to carry tens of thousands of riders daily, the LRT was billed as a potential boon to businesses along and near the route, segments of which contain clusters of immigrant-owned businesses. According to LRT proponents, increased foot traffic around stations would expose the businesses to more customers, and commuters passing by on trains would see the businesses’ storefronts.

But for this optimistic vision to become reality, businesses would have to survive during lengthy periods of construction that would obstruct regular and potential first-time customers from gaining entry to a business or even seeing its facade. For Zabel and her colleagues at Springboard for the Arts, this represented an opportunity to engage artists to help find a solution.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What can artists bring to this challenge?’” she explained. “For us, community development and economic opportunity for artists are really linked, and we thought artists could bring really creative solutions to the businesses along the light rail route.”

Partnering with Twin Cities LISC and the City of St. Paul, Springboard for the Arts launched a program called Irrigate. Irrigate trained neighborhood artists to work with nearby businesses along the LRT line to help them create place-based projects that would bring energy and attention to the area and help build social and economic capital. Nearly 600 artists who lived in neighborhoods along the route went through a one-day workshop on community organizing and placemaking, and then some used grants of approximately $1,000 to create projects that were, in Zabel’s words, low-risk and high-reward for all the people involved.

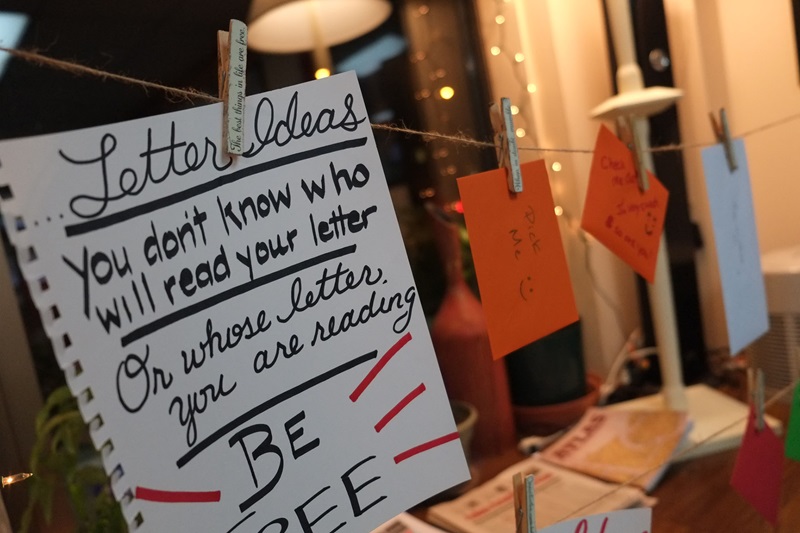

The projects varied widely in medium, from the stained-glass installation described earlier to a monthly jazz concert at a Vietnamese restaurant (where live jazz hadn’t been performed before) and a project that involved sharing anonymous, hand-written letters at a Thai restaurant. Another artist held a weekly Zumba class in a parking lot and wrote a song-and-dance sequence called “The Light Rail Shuffle” that evoked the historically African-American neighborhood’s past experiences with disruptive construction projects—specifically, Interstate 94, which now bisects the community—and speculated on how the LRT line would affect the area. For each of the projects, artists intended to spark public interest and participation and help promote community connections while supporting neighborhood businesses.

Zabel described how one café, the Black Dog Coffee and Wine Bar, teamed up with an artist to construct a giant dog puppet for someone to sport around the neighborhood. Scaffolding covered the entire building in which the café leased space and obscured the business’s sign from public view. The idea behind the costume, she says, was that if people couldn’t see the café’s sign, why not bring the sign—a giant black dog—to the people?

“For all of these partnerships, what we were really trying to do was change the narrative of the construction from negative to positive,” she explained. “If I read a quote from a business owner describing the traffic around the business as being terrible, then as a consumer, I have no interest in going there. But if I hear about a giant black dog walking around the area, that’s something I might want to see for myself. If we lift up the assets instead, telling people why it’s worth coming here, then they’re more likely to visit.”

According to Zabel, Irrigate sponsored nearly 200 projects throughout the LRT construction and attracted thousands of people to sites such as parking lots and restaurant dining rooms where artist-inspired creations changed the story line from one of inconvenience and disruption to one of creativity and community.

Leveraging cultural nodes

Since 2006, the Asian Economic Development Association (AEDA), a nonprofit organization located on University Avenue, has been helping small businesses and individuals in the Twin Cities by providing technical assistance, lending, financial education, and credit building services. As AEDA’s name suggests, most of the clients it serves are Asian. Moreover, many of the businesses surrounding its offices in the Frogtown neighborhood of west central St. Paul are owned by first- or second-generation Asian-American families.

With construction of the LRT line looming, most of these business owners worried about their bottom lines. A sustained disruption to their establishments could lead to serious financial hardship, especially for those enterprises where a handful of paying customers could make all the difference. AEDA recognized this collective worry. But instead of focusing on the negative possibilities, the organization saw an opportunity: to implement a creative, place-based economic development strategy. Drawing inspiration from the concentration of nearby Asian-owned businesses, AEDA branded the five-block stretch of University Avenue surrounding its offices Little Mekong.

“We wanted to introduce a name that recognizes the large number of southeast Asian-owned businesses here and creates this sense of destination,” said Va-Megn Thoj, AEDA’s executive director. “We’re changing the perception of the area in a positive way—getting people to talk about the restaurants, cafés, and other businesses here and all the area has to offer.”

In a sign that the Little Mekong designation is recognized by more than just AEDA and the businesses in the immediate area, the Metropolitan Council, the regional planning authority that oversaw the LRT construction, names the cultural district in some of its marketing and outreach materials. It also funded Mekong River-themed artwork for the LRT station in the center of the district.

In addition to creating an identity for the business district, AEDA has embraced the idea that creative placemaking can not only drive economic development but also solidify the neighborhood’s identity. In 2012, after launching the Little Mekong branding campaign, the organization added creative placemaking to its program offerings in order to support arts and culture initiatives in the neighborhood, which has a poverty rate approaching 38 percent1 AEDA teamed up with Hmong American Partnership, the Saint Paul Riverfront Corporation, the City of St. Paul, and local artists to help create Little Mekong Plaza, a community gathering space in the middle of the newly branded stretch of University Avenue. The plaza’s design was informed by community charrettes.2 and features green space, murals, and public art installations that reflect the diversity of the neighborhood, whose largest populations are Asian (35 percent) and African American (30 percent).

“The plaza is one of the few healthy, physical spaces in the area that people can go to,” said Oskar Ly, a former artist organizer at AEDA who worked on the Little Mekong Plaza project. Noting that there is limited green space in the Little Mekong area, Ly added, “It’s a real asset in the community.”

To further advance arts and culture in the area, AEDA recently opened a space in its offices that the organization will lease as a business incubator facility for local artisans. Ly explained that the space is intended to help small arts-based enterprises and cultural groups get a foothold in the Little Mekong area and ultimately find their own homes outside of the AEDA offices.

“We want to help them find roots here,” she said. “We really want the arts environment here to thrive.”

Using arts to focus on the “people stuff”

While some forms of creative placemaking have the primary goal of promoting community identity and economic development, other initiatives are intended to focus more on resident empowerment and connectivity to the neighborhood. These efforts aim to build on somewhat nebulous concepts like social capital and neighborhood fabric, which metrics like sales receipts can’t really quantify. One organization undertaking such an arts-based, resident-oriented form of community building is the Pillsbury House and Theater (PH+T), the arts wing of human service organization Pillsbury United Communities.

“We kind of imbue arts and culture into most of everything we do,” says Mike Hoyt, creative community liaison at PH+T, which is located in Minneapolis in an area where nearly a quarter of the residents earn incomes that fall below the federal poverty line.3 “While we definitely want to support small businesses and economic development, when it comes to creative placemaking, we’re more interested in the ‘people stuff.’”

PH+T launched two programs in 2012—Arts on Chicago and Art Blocks—wherein artists create public projects within the four neighborhoods surrounding the organization’s performance theater. The goals of the two programs are to expand access to neighborhood-based arts-oriented community development activities, strengthen residents’ attachment to their neighborhood, and promote residents’ sense of personal and collective agency. According to PH+T, since the programs’ launch, thousands of area residents have participated in scores of neighborhood-based, artist-engineered projects.

Hoyt described one such exercise that captured the essence of the type of creative placemaking that PH+T pursues: the sponsorship of a resident photographer, Xavier Tavera, to take portraits of all 16 families living on an individual block in one of the neighborhoods that PH+T serves.

“These were stunning, large-format photographs that the artist printed and displayed at a gallery in the heart of our community,” he said, explaining that on the night of the exhibition’s opening, a bus circulated throughout the neighborhood to shuttle residents to and from the gallery. “The event was really about [residents’] meeting their neighbors and connecting to the people whom they might recognize by face but might not know by name.” (See the sidebar below for more examples of PH+T-sponsored community arts projects.)

Intermedia Arts is another organization that seeks to catalyze positive community change through arts-based programming. Working largely with underrepresented populations (e.g., people of color, youth, and members of the LGBTQ community), the Minneapolis-based arts center sponsors a range of projects that employ a wide variety of media: performance, visual and literary arts, film, and music. While social-change outcomes associated with these projects largely depend on direct collaboration with community members (as is the case with most resident-oriented, creative, community-building endeavors), one program Intermedia Arts launched in 2013 sought to effect community-wide change through a collaboration with the city government. Called Creative CityMaking, the program embeds artists within a handful of departments of the City of Minneapolis to change municipal policies and practices collaboratively—a top-down approach seemingly anathema to grassroots creative placemaking. Creative CityMaking is a multi-year collaboration between Intermedia Arts and the city’s Art, Culture and the Creative Economy program.

“Creative CityMaking is a unique approach to creative placemaking in that it focuses on process and equitable systems change,” said Carrie Christensen, a program manager at Intermedia Arts. “We have started to refer to our work as “equitable creative placemaking” rather than creative placemaking because we are constantly working to hold racial equity at the center of our work, questions, and conversations.”

Artists work with staff in departments like Community Planning and Economic Development and the City Clerk’s Office to help city personnel rethink some of their core administrative tasks and procedures, particularly ones that have an effect on resident equity. Artists, Christensen said, tend to think differently about decision-making processes, and they can apply these perspectives to help departments tackle persistent problems. For instance, Minneapolis’s Department of Regulatory Services focuses a large portion of its work on regulating rental properties. Given the emphasis on dealing with property owners, how do renters—many of whom are low- to moderate-income people of color—offer feedback to this department to ensure that their interests and the department’s interests are better aligned? The Creative CityMaking program placed artists within the department to help create arts-based pathways to ensure renters are heard.

Christensen said that after rigorously analyzing the meaning of “tenant engagement” and clarifying the vision of the project, the artists decided on a three-pronged approach to amplify renters’ voices: they held a series of highly interactive theater workshops for Regulatory Services staff to promote personal reflection and build intercultural competency, they organized external community engagement activities during which staff worked directly with tenants, and they hosted a series of collaborative learning activities that brought Regulatory Services staff together with tenant community members to work on issues that most affect renters.

“For us, a huge measure of success is that this work is now moving from being exclusively grant-funded to being funded and staffed by the City of Minneapolis,” said Christensen, noting that the Creative CityMaking program has embedded 16 artists over the past four years. “We started this partnership in just one city department in 2013, expanded to five departments in 2015, and will be working in up to eight departments moving forward. We’re thrilled with the progress.”

Measuring the impact

The benefits of creative placemaking can be challenging to evaluate. Economist Anne Markusen and arts consultant Anne Gadwa, who examined creative placemaking in a white paper for the National Endowment for the Arts, noted that “it is quite difficult to determine the precise impacts of a localized intervention because so many other things are simultaneously influencing the environment.”4 Nevertheless, funders—as well as the organizations themselves—want confirmation that their investments are making a difference.

In order to address the evaluative needs of foundations and local governments who have underwritten these efforts, organizations have tried creative ways to assess the effects of their specific efforts on the broader environment. For example, PH+T undertook a rigorous evaluation to gauge the effectiveness of its Arts on Chicago and Art Blocks programs. Using a variety of data sources (e.g., artists’ final reflections, data on resident participation, and residents’ survey responses), the organization discovered that its two programs succeeded in a number of measures, such as enhancing residents’ access to arts programming while increasing their attachment to their communities, but had a harder time proving improved agency.

“We want to hold ourselves accountable to make sure our work is meaningful,” said Hoyt, noting that a third of the organization’s roughly $2 million budget goes directly to paying artists. “In a way, we look at the evaluations as an organizational improvement tool. How can we program differently to connect to more people? And what can we strip away that isn’t working?”

Zabel, of Springboard for the Arts, said that her organization hired a public relations firm to gauge the media narrative around the six neighborhoods adjacent to the LRT line where artists worked with business owners on creative placemaking projects. Between 2010 and 2014, more than 50 million positive impressions appeared in print and online.

“To be in the paper every week because something weird or wild and creative was happening was really reinforcing for the neighborhoods,” she said. “Our efforts to put artists out there definitely contributed to that. For us, community development and art are really linked.”

Endnotes

1 From the Minnesota Compass profile for the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale Neighborhood of St. Paul, which uses 2010–2014 American Community Survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2014, a four-person family—two adults and two children—with a household income of less than $24,418 lived in poverty.

2 A charrette is an intensive planning session in which community members work collaboratively with architects or other designers to create a vision for a public space or other development.

3 From the Minnesota Compass profile for the Powderhorn Community of Minneapolis. See footnote 1 for more information on the federal poverty threshold.

4 Creative Placemaking, Markusen Economic Research Services and Metris Arts Consulting, 2010.