Lawrence Katz is an institution in labor economics—indeed, in economics as a whole. As editor of the Quarterly Journal of Economics since 1991, principal investigator of the decades-long Moving to Opportunity program, co-founder and co-scientific director of J-PAL North America and collaborator with Claudia Goldin in pathbreaking research on the causes and consequences of rising education levels, he has been a singular force in shaping the field.

The Harvard professor published his first academic research before he’d graduated from college; that precocious paper—on how restrictive land-use regulation denied opportunities to lower-income families—launched an enormous body of work on barriers (and paths) to economic equality, mobility and opportunity.

The conversation below touches on a portion of that work: the gender pay gap; declining labor share and growth of “superstar” firms; the college wage premium, technology and economic inequality; the impact of neighborhood poverty on low-income families; and the fissuring of U.S. workplaces through labor contracting, among other topics. But Katz’s research goes far beyond. He’s investigated areas as disparate as for-profit colleges, oral contraceptives and women’s careers, effects of the minimum wage, immigration and employment, and the economics of crime.

Central to all of Katz’s research are enduring and emerging economic policy issues that affect the well-being of average, often disadvantaged, people. Other commonalities are solid theory, meticulous methodology and lucid exposition. Few economists write as clearly as Katz, and that gift extends to his oversight of the QJE, one of the discipline’s oldest and most influential journals. In that role and particularly as doctoral adviser to nearly 200 Harvard graduate school students, he has shepherded the careers of scores of leading economists and helped form the contours and direction of economics for decades to come.

Asked why he became an economist, he first jokes that the intro class in political science started too early. “I wasn’t going to get up at 8 a.m., so I ended up taking economics two hours later and did pretty well.” Deeper reasons: His mother worked with disadvantaged children from poor Los Angeles communities, and he himself was one of the poorer kids in a richer neighborhood. That exposure shaped his career. “Economics combines rigorous scientific approach and methodology of theory and evidence with the sort of people issues I care deeply about,” he says. “That’s really why I think I ended up here.”

As he spoke those words, “here” literally was a Minneapolis conference on easing access to better opportunities, neighborhoods and jobs through improved home building and purchase policies—a still-pressing issue he’d unearthed nearly 40 years ago.

Interview conducted July 18, 2017.

Women working longer

Region: I want to start with a question about research you’ve done recently with Claudia Goldin, documenting that a large share of women are working much longer than have previous generations—well into their 60s and 70s—and working full-time.

Could you tell us some of the details on this? When did the trend begin, and what’s the explanation, in your view?

Katz: A lot of attention has been paid to the slowdown or even decline in labor force participation among women in their 20s, 30s and 40s after decades and decades of rising. There’s been much discussion of things like the “opting out” phenomenon. But what’s missing is that while today’s 35-year-olds aren’t working a lot more than their cohort a decade or two ago, what we see for women 55 years old and older is consistent increases over the past three decades. And the employment increases are larger for older highly educated women.

Moreover, it doesn’t simply look like a phenomenon of people losing a lot of money in the Great Recession and putting off retirement because they can’t afford to retire.

Region: The trend started before the recession.

Katz: Yes, it started before, and it looks much more like women have moved into careers that are increasingly fulfilling. A very strong predictor of whether you persist in the labor market, beyond just having a higher-wage job and a good position, is how satisfied you are with your job. It really seems to be that women working longer reflects the importance of work and career to women’s identity. Women have had the ability to move into more professional, long-term jobs. In many cases, they’ve had time out for having kids, but now they’re in a part of their career where they’re really doing fulfilling things in their 50s, 60s and even 70s. In many cases, this is true even when the husband retires, yet the wife continues to work and to thrive in work.

Now, there clearly are some women being forced to work when they suffer a big drop in their portfolios, but most of the driving force here seems to be choices—of women being in types of positions that they find really are meaningful. Even when women shift into partial retirement, they often come back into those types of positions when available.

The pattern is much broader than the United States. We’re seeing similar things, from lower levels of older women’s initial labor force participation, in Germany and in France. Now, a lot of European countries used to have lower retirement ages for women than for men, and there were quite severe taxes on continuing to work past that age. But when some of the adverse incentives for continuing working were removed, we’ve seen an increasing trend toward women working longer, particularly highly educated women already in the labor market.

Region: Just in Germany and France?

Katz: No, actually in a wide range of countries now.

Region: And this article is a preview of your book together, to be published this year?

Katz: Claudia and I—and she should get most of the credit for this project—brought together a group of scholars to analyze this phenomenon. We’ll be publishing a book later this year, Women Working Longer, that incorporates much of that work. Ours is the first piece in that book; it’s an introduction and overview of the facts and trends. Then there’s a series of great papers by leading scholars on different components and elements of changes in older women’s labor market participation and time use.

What is the role, for example, of the teaching profession? Back in the 1960s, college-educated women in the labor market were predominantly teachers, and teachers had particularly strong incentives to retire early. So, how much of the women-working-longer phenomenon from college-educated women is from women shifting out of teaching into other higher-earning professions, typically without such strong early retirement incentives?

There are also attempts to look at another increasingly important issue: One of the drags on women working longer is the requirement faced by many women in their 50s and 60s to care for ailing parents as life expectancy rises. Who faces the burdens of that care, and what impact does it have on labor force participation?

Other work looks at the role of retirement income and saving, and financial sophistication. Some research looks at differences by race. For African American women, for example, there isn’t as much of a rise. African Americans, in fact, have always worked throughout the adult life cycle and, as a group, they have more health problems and less savings from not having as lucrative career opportunities.

So, there’s quite a range of work in the book. The Sloan Foundation provided us with funding, and the NBER [National Bureau of Economic Research] provided a venue to push this research. Past volumes have focused on the impacts of retirement systems and trends for men. There has been relatively little focus on the growing importance of women in the labor force for studying changes in age of retirement and labor market participation trends for older individuals. For policies ranging from Social Security to issues of long-term care and childcare, it’s very important to understand this phenomenon.

Gender pay gap

Region: You and Claudia have also researched the gender pay gap in great depth, looking particularly at pecuniary penalties for workplace flexibility related to family—career interruptions, shorter hours, workday flexibility, that kind of thing. The penalty varies with age, over time and by profession.

Can you tell us about this work? One of your papers, for instance, focuses on how the pharmacy industry is one of the most gender egalitarian job sectors, while finance and corporate jobs are far less gender equal.

Katz: Claudia’s American Economic Association presidential address in 2014 is really the seminal paper synthesizing this work and putting together an insightful framework to think about how different jobs have different costs of temporal flexibility.

That is, if a job has lots of highly idiosyncratic components where different workers can’t substitute easily for one another—a specific lawyer, say, always has to be there to deal with a particular client and there’s no substitute—so for that job, there are very high returns to being able to work long hours or to sort of be on call. That job requirement generates a premium and it’s very expensive to firms—productivity falls—when you don’t satisfy that requirement. In that situation, there’s a high pecuniary penalty for workplace flexibility, and if a woman needs that flexibility for her family responsibilities, there’s going to be a large gender pay gap.

Now, as you mentioned, some of these gaps are much larger in sectors like in the corporate and financial world. Other professions have evolved over time toward much smaller gaps, for reasons potentially having to do with changes in work organization, technology and incentives. Our best example is the pharmacy sector, which we wrote about in a paper that came out in the Journal of Labor Economics in 2016.

If you went back 40 or 50 years ago, pharmacy was a highly male-dominated profession. It was largely independent pharmacists who worked long hours being the person who ran the business, supervised technicians, compounded drugs and dealt with vendors. Today, it’s still a highly skilled profession requiring a lot of training, even more than in the past, but it’s been reorganized in ways in which different pharmacists with information technology can stand in for one another. They don’t have to keep everything in their own core memory; you know, each idiosyncratic component of a client and every drug interaction can now be easily accessed for electronic records.

Region: You found that in addition to technological change, institutional evolution played a part.

Katz: Right. With the growth of pharmacy chains and hospital pharmacies relative to independent ones, there was the ability to have scale and to have multiple teams of pharmacists who substitute for each other. So pharmacy has become a highly skilled and valuable profession with very little cost to taking time off. That is, two pharmacists working 20 hours a week seemed to be pretty much a perfect substitute for one pharmacist working 40 hours.

Two lawyers working 20 hours a week, in contrast, are not a perfect substitute for one working 40, and two investment bankers working 40 hours a week can’t replace one working 80 hours.

What you now see is that pharmacy went from one of the biggest gender-gap professions to having the lowest gender earnings gap of any major profession, and to being one of the highest-earning professions as well. So it’s a serious profession, and it’s a lot of training, but it’s clear that there is the possibility of developing ways to hand off things.

We see similar things in medicine where certain specialties that once had very large penalties to not doing super-long hours started being reorganized in ways that use teams so that workplace flexibility is possible. This happened, for instance, as the share of female physicians in OBGYN rose; now whoever is on call can deliver your baby because OBGYNs will work as a team.

In many law firms, though, there’s still this odd feature that’s identity-specific; somehow you can’t have some other lawyer at your firm deal with what seems like some generic legal case. But a lot of savvy companies have figured out that rather than working with a traditional law firm, they can create a group of inside corporate counsels by hiring individuals, often women, who want more balance in life. The company can actually get more talent, and the lawyers get a much more flexible work life.

There are still large barriers in fields like finance where it’s very tough to break in. But, generally speaking, we suspect that these barriers can diminish, and we’ve certainly seen that part of narrowing the gender gap is the way the organization of work and technology has changed this.

Education and technology

Region: In The Race between Education and Technology, your 2008 book with Claudia, you argued that trends in the relative supply of and demand for educated workers went a long way toward explaining the evolution of education wage differentials, and also trends in economic inequality.

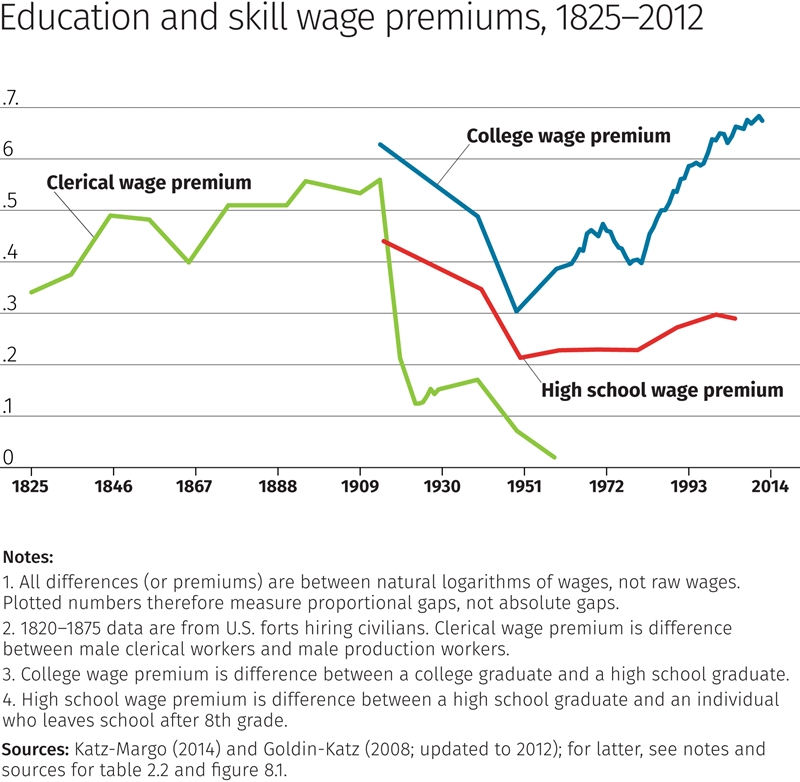

One key chart from your book shows that as the supply of educated workers rose relative to demand for them, the college wage premium declined from 1915 to the mid-’50s, ‘60s. But after 1980, as education levels stagnated, the wage premium began to soar to near historic levels by the early 2000s.

Katz: And it’s continued beyond then: In 2016, the college premium continued to grow. This other chart is sort of my favorite.

This tries to put it all together for 200 years.

Region: Back to 1825!

Katz: Yes. There is no systematic survey or data prior to the 1940s census on wages. But there was one very important employer in the United States who kept good records going back to the 1820s: the U.S. military when they were hiring civilian employees at forts all around the country. They would hire a blacksmith or clerk or day laborer and write down the employee’s characteristics and the wage they were paid and look at the gap between, for example, a clerical worker and a production worker working at a fort.

The chart starting with the 19th century skill premium data based on the military wage series put together by the economic historian Bob Margo shows that there was a rising skill premium (that fed into the high school movement) prior to the big decline in the early 20th century. Our best evidence suggests that with the shift from the artisanal shop to larger and more mechanized factories, there was a big demand—with the growth of scale of individual enterprises—for engineers, managers, accountants and clerks relative to craft workers and even relative to other production workers.

These labor demand shifts favoring more-educated labor were part of the economic motivation for the United States investing so much in the early 20th century in high schools. And this huge surge of education played an important role in reducing inequality from this large wage premium that Paul Douglas called the decline of “non-competing groups” in the teens and the ’20s.

Region: It plummets in about 1915.

Katz: Yes, around World War I, and then persists. There was a wonderful period from about 1950 to the early ’70s where everything seems pretty stable and you have rapid income growth for everyone, so we were growing rapidly and growing together. Since that period, we have been growing more slowly and growing apart with rising inequality and educational wage gaps. We argue that the demand for better-educated workers has been pretty steadily growing throughout the past couple of hundred years, but the growth of supply of skills and access to education have varied a lot across time periods, with a slowdown since 1980.

Implications for economic inequality

Region: As you just mentioned, the college wage premium has continued to increase to the present day. What are the implications for economic inequality?

Katz: If you look at the past 30 years, there’s been a big increase in inequality, which you can measure by the Gini coefficient. You can do this for individuals, for family households. A big part of that increase is at the very upper end—which I won’t claim is largely the education return. But even if we exclude the top 0.5 percent [of the income distribution], there are very large differences; we estimate that, as recently as 2013, about two-thirds of that [increase in inequality] is due to the growth of the educational wage premium. Almost all of that is post-secondary college and post-college. So, if you’d kept the college premium at the 1980 level, you would’ve seen only a third as much of the growth of U.S. earnings inequality.

This is very consistent with recent work by people like Fatih Guvenen in Minnesota, using matched employer-employee data and finding that about three-quarters of the growth of inequality is the growth of dispersion of person effects of which the vast majority are the differences by education.

It’s clearly an important component and, while more people are going to college now in response to the rising education premium, the United States has not done anything like the high school movement, which essentially provided access to high-quality high school to pretty much everyone, the major exception being African Americans in the Jim Crow South until much later.

What the government has done—in the ’50s and ’60s, even into the ’70s—is invested heavily in high-quality colleges. Think of University of California campuses or Florida State. But since then, there’s been very little investment in expanding quality higher education. There’s increased crowding at community colleges and state universities, and states have greatly cut back on appropriations for higher education, particularly in the Great Recession.

The federal government has continued to have an important role, but it’s done it with flexible support through Pell grants targeted to low-income students. The problem is that we’ve had a surge of really low-quality colleges, and the worst of that is the for-profit sector, which Claudia, David Deming and I have studied. Particularly from the late ’90s to 2011 with this very large wage premium and funneling more federal funding into loans and Pell grants, a big part of that marginal growth—particularly for disadvantaged individuals—was at for-profit institutions for both associate’s degrees and bachelor’s degrees.

It’s been a bit of a disaster. Even though these for-profit institutions have tried to be up to date, very flexible, with high-quality online instruction, we have repeatedly found very little economic return to degree programs at for-profit institutions; instead, it’s become a massive debt trap. I think there is something to be said for the quality and capabilities, the faculty, the peer effects of a traditional public or private nonprofit university.

So, rather than what would’ve been the equivalent of the high school movement—developing more University of California campuses or more Florida public universities, so we weren’t rationing access to quality public colleges—we allowed the for-profit private sector to come in both as a nimble creative but also as an agile predator.

The market choice approach, of course, is really good for commodities someone can buy repeatedly and assess. And it works in some cases for higher education as well. Where there are clear state certification requirements, the for-profit education sector has been reasonably good. For becoming licensed in cosmetology, for instance, or hair stylists or health tech occupations, it works, and we wouldn’t want to shut down the whole sector.

For things like getting a more ambiguous business degree or getting a nursing degree, though, the quality and infrastructure just haven’t been right. But recent work has shown that where people can get into quality institutions, a state university like Florida International University, say, on the margin, they get like a 14 percent a year return. That’s clearly telling us we’re not having enough access to good quality education. Seth Zimmerman at the University of Chicago has shown this.

Region: David Autor and Daron Acemoglu write in their review of The Race Between Education and Technology that continued support for elite institutions is important for continued economic growth, but that to ensure a rising tide for all people, governments need to fund quality education for all.

Katz: It’s clear we don’t have enough. Good state universities are engines of economic mobility. Around when I was born, the state of California population was about 15 million and there were about three UC undergraduate campuses. The population had grown by about 8 million by the time I could choose a college, and there were eight UC colleges. I went to UC Berkeley.

In the past 40 years, California’s population has almost doubled again, growing by 15 million, and we’ve gone from eight UC undergraduate campuses to just nine, adding UC Merced in 2005. We’ve had a slight increase in the enrollment of each one, but not much. There’s no reason there shouldn’t be another five 30,000 or 40,000 student UC campuses given how much the population has grown.

Well, we just haven’t maintained that commitment to educate the public the way we did earlier with the high school movement. It’s a much riskier proposition to go to a for-profit college. In general, I’m very happy with relying on the for-profit private sector for most goods and services, but with purchases like education where quality is really hard to detect and purchases are not frequent and some government subsidy programs and regulations have created perverse incentives for the providers, it doesn’t seem to have worked that well.

Moving to Opportunity

Region: As principal investigator of the Moving to Opportunity experiment, you’ve gained rich perspective on the effects that neighborhoods have on children and their families.

Last year, with Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, you published new evidence that moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods had a very significant positive influence on young children in a number of dimensions, but that moving as an adolescent had a slightly negative impact. And fairly neutral for the parents.

Katz: Yes, fairly neutral economically for the parents, but very beneficial in terms of health and well-being. One shouldn’t forget that earnings is not the only thing.

Region: Absolutely. Would you elaborate a bit on the overall findings, starting with a very quick background on MTO itself?

Katz: Sure. Moving to Opportunity has an interesting history. It was brought into being based on a 1992 urban and housing bill that Congress passed soon after the Rodney King Los Angeles riots. For a brief moment, there was some focus on the problems of the inner city, and some demonstration money went to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. By 1993, there was an interagency process through HUD and the Department of Labor, where I was lucky enough to be the chief economist.

At that time, we were thinking about things like empowerment zones, and we were able to use this demonstration money toward efforts involving public housing, which was increasingly in highly segregated areas, both racially and economically. And we thought about using housing vouchers to try to help people move to better neighborhoods.

The demonstration program ran in five cities: Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, New York and Los Angeles. And the families eligible were living in public housing in the highest-poverty census tracts with an over 40 percent poverty rate.

Through a lottery, MTO allowed people to jump the queue to get housing vouchers providing housing support to live in an area of their choice. There were three groups: an experimental group that had to move to a low-poverty area if they wanted to move and received mobility counseling assistance as well, a second treatment group that received vouchers but wasn’t required to live in a low-poverty area, and a third group, the control group, who stayed where they were and kept their regular housing support. And we’ve been tracking them for 20 years.

The first question was whether we could actually get a significant number of families to move to low-poverty neighborhoods even with these vouchers. We thought that about a third of them would be able to make such moves. But, in fact, through the hard work of these families and the counselors, almost half of the experimental group families leased up in a low-poverty area.

Region: Was that uniform across the five cities?

Katz: It varied across sites. It was much easier in Los Angeles, where the housing market was more fluid. It was much tougher in New York, Chicago and Boston. Easier in Baltimore.

So, the answer to the first question was, yes, you could get families to move and persist of their own choice in these areas. The other questions were, What did moving do in the short run, and what difference did it make over the longer term?

And what we find for Moving to Opportunity is in the short run it clearly made the adults in the families happier and healthier. Measures of well-being and safety improved. There were big reductions in exposure to violence. But, economically, nothing much changed for the parents.

But it’s significant that at the time of the moves, at baseline, we asked people why they wanted to move, and very few said they were moving because they were looking for a better job. Almost always it was safety, wanting to get out of more violent areas, worried for their kids. Or it was trying to improve their housing conditions.

We saw huge improvements one year out, five years out, 10 to 15 years out in adult health. Large reductions in obesity, in depression, in diabetes and in biomarker indicators for long-term stress. This is sort of the equivalent of your best antidepressant and your best exercise and diet program in terms of long-run improvements in adult health and mental health!

So until we did the latest study on long-term effects on the kids, the message from MTO has been that there were huge benefits to a family’s well-being and health, but not much economically, and we weren’t finding much on test scores for kids. We had a little bit of evidence of positive things for girls and, if anything, the boys were looking a bit negative.

One other indicator, which we gathered through voice recordings, is the use of African American vernacular English versus Standard American English. For parents, there was no impact at all. But for the younger kids who move to low-poverty neighborhoods, we were actually finding that, even though their test scores weren’t going up much on standardized tests, they were “code shifting” in talking to a middle-class interviewer. That is, we saw significant impacts on the way they express themselves—not saying that there’s any value judgment of whether it’s good or bad, but it clearly indicated some sort of change in their usage of speech related to their changed neighborhood environments.

And we found in our 2015 PNAS [Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences] paper led by the distinguished linguist John Rickford that the change in language use seems to have been a good potential interim indicator of their later economic outcomes. When we looked at those same kids who didn’t look that different in their school performance but were less involved in violent crime as adolescents, they seemed to be assimilating types of social capital that may not show up on standardized tests, a sort of savvy of living in a different type of neighborhood.

As Chetty, Hendren and I observe, the younger MTO children becoming adults, we see them more likely to go to and persist in college, and we see them much more likely to work, and an almost 40 percent impact in their mid-20s on earnings. It really looks like a powerful impact.

Our preferred model is that there’s a short-run dislocation cost, but there’s an accumulation of new human capital or social capital from being in an environment with better schools, better economic opportunity, less crime and better health and diet. If you spend a long enough time in that neighborhood, that way more than offsets the disruption cost.

What we conclude from that is that it’s extremely important to make sure that families have access to the ability to choose better neighborhoods when their kids are young.

Creating Moves

Region: What’s next for MTO?

Katz: The next stage is called Creating Moves to Opportunity. We’re pretty convinced that Moving to Opportunity paid off for families, so can we use the existing housing choice vouchers in the United States to help families move to areas with greater opportunity for their kids? (Currently, about 80 percent of them are used in high- or moderately high-poverty areas.)

We got a consortium of public housing authorities quite interested in experimenting. We’re going to the field in the fall with our first test of this working with Seattle and King County public housing authorities. And we hope the second test may be the Minneapolis-St. Paul region. Greg Russ, the new head of the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority, was previously here in Cambridge, and he is one of the founders of Creating Moves to Opportunity. It’s very much linked up to the Minneapolis Fed work on inclusive growth and working regionally.

One of the big barriers in this work is that there’s a lot of variation across states in whether housing vouchers are portable to other jurisdictions and whether landlords can explicitly discriminate against voucher holders. In Massachusetts, there’s a lot of portability. If you have a housing voucher from Cambridge, you can move to other jurisdictions. In Seattle, many of the more affordable places with high opportunity are outside the city of Seattle, in other parts of King County. That’s something we’re trying to work out with Minneapolis too.

The goal is to figure out the most low-cost ways to help people. Is it information? Is it getting more landlord listings for housing voucher holders? Is it providing security deposits and an intermediary to help with landlords who may be worried about renting to a family that has been low-income or had past rent payment problems?

The United States spends over $40 billion a year on federal low-income housing assistance programs, most of which leaves people in the same neighborhoods they’d be in without public support. Our hope is to find ways of using existing resources more effectively.

Opportunity and Inclusive Growth Institute

Region: We were honored to have you join the advisory board of the Minneapolis Fed’s Opportunity and Inclusive Growth Institute. How can the institute best work toward the goals of greater economic opportunity for those without and income growth for all population groups? And to what extent do you see the institute’s work complementing that of J-PAL [Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab] North America, of which you’re co-founder and scientific director?

Katz: One thing the institute can do, I think, is to galvanize the efforts of researchers working on opportunity topics. There’s an amazing group of scholars within the Federal Reserve System, and having one place that both publicizes and integrates all the work being done on the wide range of issues related to inequality, labor markets and housing markets that link up with the financial system is very important. I think that’s one thing that having a dedicated institute will be able to do. The other is to provide a hub for scholars from academia to get time off and, through the institute’s visiting scholars program, foster collaborative work.

And, you know, I think J-PAL has a lot of complementarity with the institute. At J-PAL North America, we’re really focused on trying to use the tools of randomized controlled trials, as we’ll be doing in the Creating Moves to Opportunity in Seattle and King County, as one way of testing different models. An incredibly important input to that is using the detailed administrative data to get the facts. Chetty and Hendren have been leading an effort to put together what we call opportunity maps using tax administrative data sets to match where children grew up early in life to their later adult outcomes to see which areas give low-income kids the best odds of upward mobility. Another thing is to link that up to housing prices. Where are there the best opportunity bargains to find a place you can afford with a housing voucher that has the best predicted outcomes for your kids?

It could be a combination of big data work that people like Fatih Guvenen are doing using administrative Social Security and tax data to examine life-cycle earnings inequality trends or new approaches to looking at issues like redlining in different neighborhoods. Access to financial information and banking information that the Fed has is crucial. And the regional Feds each have strengths. Scholars at the Chicago Fed such as Daniel Aaronson, Daniel Hartley and Bhash Mazumder, for example, have been doing very interesting historical work recently on redlining and housing segregation. A huge advantage that Federal Reserve research economists and policy people have is access to administrative data on the financial system. That can inform policy work on housing and labor market issues.

Declining labor share and superstar firms

Region: For decades, an enduring regularity in economics was the two-thirds of GDP that accrued to labor. But economists have now documented an erosion in labor’s share that began in the 1980s and became particularly strong in the 21st century.

In a paper presented yesterday at the NBER Summer Institute, you and your colleagues argue that “superstar firms” are the prime force behind labor’s falling share.

It’s an intriguing theory. Could you describe the idea and some of the evidence behind it?

Katz: Sure. The basic idea is that, industry by industry, large firms are becoming increasingly dominant. It’s well known that there’s a general trend toward rising concentration in U.S. industry, and there seems to be a similar trend in most other countries that we’ve looked at. In almost every industry, the largest 20 producers, the largest four producers, the largest single producer seem to be increasingly important. And the higher up you go, the bigger. So there’s growing concentration of economic activity in what we call superstar firms, the top firms in each sector. In many cases, those firms cross many industry boundaries. Amazon, for example, is in lots of product markets.

There are two broad hypotheses for that. One is that these firms are much better able to take advantage of new information, technology and network effects. They’ve been dynamic, technologically capable and investing heavily in innovation; we find some evidence suggesting that superstar firms have become disproportionately important in sectors where you see greater patenting activity, greater R&D, greater productivity growth. They clearly are taking advantage of new technology more than others. That’s a good thing, economically, but it also means they become very dominant and then have the ability to charge higher markups.

The second hypothesis is that they might also then be able to prevent entry. Microsoft is an earlier example of that, but we think a lot of the new large guys have that ability too.

So there are rising economies of scale (or scope) that allow superstar firms to dominate because they’re more productive, and they also may have an ability to get more market power. Both of those things tend to allow them to have lower labor share: They have a higher markup, and they use technology in a way that they need less labor.

We wanted to go into the microdata and ask, How much of the fall in labor share is a reallocation to the biggest producers who always have lower labor share, and how much of it is that the top firms themselves are just becoming much more efficient or much less labor intensive?

We found that throughout the economy, the majority of the decline in labor share is this reallocation effect. The total sales, or value-added, in the economy is shifting toward these larger superstar firms—that’s what the growth of concentration shows—and these firms have lower labor share than the average firm. So most of the growth in the decline of labor share is this between-firm reallocation effect. As the big firms become a larger part of the economy, labor share mechanically falls because those big firms have lower labor share.

And not only are they getting bigger, but as they get bigger, they take advantage of new technology that is more productive and uses less labor. Some of that is through technology, but some of that is probably through outsourcing and fissuring of employment. To the extent that it’s pure fissuring domestically, that’s no change in aggregate labor share. If Goldman Sachs, for example, outsources its janitorial services, that decreases the firm’s labor share, but there’s no national decline in labor going to janitorial services.

The normative implications depend a lot on whether you think this is pure efficiency and consumers benefit or you think that these firms are now huge monopolies that are going to take advantage of both workers and consumers. There’s growing evidence that that second component is worrisome from the rising markups in many parts of the economy.

Implications for inequality

Region: What are the implications for inequality? At yesterday’s discussion of the paper, you seemed a bit frustrated by those who implied that the paper was saying this superstar phenomenon is the primary source of U.S. inequality trends.

Katz: It’s important to emphasize that this is a paper about the decline in labor share. Superstar firms and declining labor share are important phenomena, but they’re not responsible for most of the growth of inequality. Most of the growth of inequality is due to the race between education and technology, and growing inequality among workers. Admittedly, in the 2000s, because capital income is so much more concentrated than labor income, the decline in labor share is an important component of growing inequality. But it is not the most important component.

It does have indirect effects on that inequality. Guvenen, Nicholas Bloom and others have shown that as superstar firms have grown, they’ve increasingly become employers of elite workers and found ways to contract out much of the non-elite work. As their sales go up, employment is not growing proportionately. Some of that is growing productivity, but a lot of it is outsourcing. When janitors work at Goldman Sachs as Goldman Sachs employees, they tend to share in the firm’s huge productivity benefits and huge rents. But if they work for Joe’s Janitorial Services, they no longer share in those rents.

Research using matched employer-employee data that people like Fatih and Nick are doing shows that about a third of the growth of inequality is this increased segregation or sorting. It used to be that General Motors had people throughout the education and income distributions working there; whereas, today’s large firms, the Apples and Goldmans, tend to mainly directly employ college graduates and elites. It’s not as important a source of the rise in inequality as the rise in market return to college education regardless of where you work, but it’s become a big component.

It’s also particularly politically sensitive, and I think it fed into the recent election cycle: The idea that there used to be a sense of “you could get a job with a good employer in your town, even if you weren’t a college graduate, and it would lead to a long-term (and often unionized) job with reasonable benefits.”

But if those employers now have been bought up by private equity and other “big guys,” and they, for the most part, only directly employ elite workers who have gone to college, and contract out a lot of lower-level work or hire mainly through temporary help agencies, then many locals may perceive that they no longer have a shot at a good job in the way their parents did.

This is inequality beyond just the pure race between education and technology. It’s the sense that there used to be a pathway, that if you worked hard you could get a good job and share in prosperity—if General Motors did well, you would do well. The sense that that pathway is gone has had a large political effect. And it’s led to counterproductive views that if we simply cut off international trade, that this would reverse that lost opportunity. But you know, we’re not going to go back to the way we were producing things in the 1950s or ’60s. No one wants to buy black-and-white TVs. You could employ a lot of workers making black-and-white TVs and pay them the wages we paid them in the 1960s, but I don’t think there’s any market for it.

We need to think about how to equip people to move into the in-person service jobs that aren’t going away or into the new, more analytical jobs. That involves better college education but also things like sectoral employment training programs and apprenticeship programs. I’ve been working on an evaluation of some sectoral employment training programs that are trying to get at the fact that there are a lot of skills that an individual employer isn’t going to train workers in because those workers may not stay with them. Why not? If a firm trains a worker in a marketable skill that appeals to a broad range of employers, but the firm doesn’t retain the worker’s loyalty with benefits the way they used to, then that worker may go work for someone else.

So it might make sense for an entire sector to provide training, whether it’s airlines wanting more airline mechanics or banks wanting people with certain IT skills or hospitals wanting people who can do a particular sort of medical bill coding. Potentially, it could be a partnership between a community college or a nonprofit and some set of employers. They could develop curricula that are valuable for jobs now in the industry where no individual firm would provide training because they’re scared their trainees are going to be poached. That could be a sweet spot to try to provide training in marketable skills. We have two randomized control evaluations now that have shown pretty positive results, on the order of 15 percent to 30 percent earnings increases a few years out.

And I think we’re going to need to think seriously about making the earned income tax credit more generous and potentially providing wage subsidies for those with a really tough time getting employed. In my view, those policies are a more likely American alternative than a universal basic income not linked in any way to work, which I suspect has little political traction in the United States. I think linking an effective safety net to work for adults and having a more generous and fully refundable child tax credit or child allowance would be a more sensible approach to giving everyone an opportunity at a reasonable job and having all children supported.

Alternative work arrangements

Region: You’ve been working with Alan Krueger on “alternative work arrangements”—employment through temp agencies, on-call agreements, freelance gigs, short-term contracts—finding that they’ve become increasingly common in recent years, rising from 10 percent of workers in early 2005 to nearly 16 percent by late 2015. Indeed, it’s a longer-term phenomenon than that: a doubling in the share of workers reporting Schedule C income from 1979 to 2014.

What’s behind this phenomenon? Business cycles and the Great Recession? Technological change? An aging workforce?

Katz: We’ve seen a big growth of independent contracting and contract companies, and we think there are several causes. Some of it is positive. The vast majority of people who are freelancers say they like it because of the ability to have work-life balance and choose their own work. But they worry a lot about lack of benefits and instability of income. Most people who work for temporary help agencies or contract firms would rather have a more permanent arrangement with a regular employer. So that looks much more involuntary.

Some of it is facilitated by new technology: apps and other things that enable use of capital like a car that wasn’t being used; so that’s good, a more efficient resource use. But it’s much broader than the online economy. We showed that’s only a very small part so far.

A lot is caused by anything that makes inequality rise, including the college wage premium. Imagine a firm that hires a lot of college graduates but also hires its own janitors and its own food service workers, and it pays a really big premium. It may offer good health benefits, for instance.

If there are rules that say the company has to offer the same health benefits to all employees to get tax benefits, then if janitors are part of the company, they get offered the same health benefits as the managers and the CEO. But if the janitors work for a contractor, the company doesn’t incur that expense, so it’s an incentive to outsource. Anything that creates this sort of big difference in wage premium between janitors and middle managers and CEOs will generate that desire to contract out and claim they’re not “my” employees.

Region: So that’s the “fissuring of U.S. workplaces” that you and Krueger refer to.

Katz: That’s the fissure. Part of the trend, as I’ve said, is due to improvements in productivity and technology. But fissuring is a major part of it. This actually happened here at Harvard University where in 2001 there was a living wage movement and workers took over Massachusetts Hall. The settlement of that strike was to set up a student, union, faculty and administrator committee that I headed known as the Committee on Employment and Contracting Policies at Harvard, or the “Katz committee,” as it got to be called.

The driving force was that Harvard had been contracting out a lot of janitorial work, security guards, food services. Part of that was to undercut the union wage and to get out of paying the same benefits that were really expensive that we offer. But there were also efficiency incentives. Harvard Business School, for example, felt that Harvard University Dining Services could not provide the quality of services needed for a function for business executives. So there were legitimate productivity reasons to hire a company that specialized in higher-end dining rather than food services for college students.

We created a Wage and Benefits Parity Policy, which said that any unit of Harvard has the right to contract out any of its service operations, but it should do that because there’s a legitimate productivity rationale, not just to undercut the legitimately bargained wages of in-house union workers.

Region: So you created a parity policy.

Katz: Right, parity: You have to provide the same wages and benefits. If the science center hires a contractor to run its café, it has to pay the same wages and benefits as we pay Harvard in-house workers.

Deborah Goldschmidt and Johannes Schmieder at Boston University have done very good work for Germany showing that for the same worker doing the same job—one year, they’re a Daimler worker, and the next year they’re at, say, Dietrich’s Cafeteria Service—in the same cafeteria, and their wage starts declining. This is the galling aspect of it. You’re doing the same job in the same place, but you’re no longer sharing in the benefits.

An inclusive economy has got to find a way that not just elite workers and shareholders share in the benefits. More companies need to adopt policies like those we enacted—after a struggle—at Harvard. Some firms in Silicon Valley improved contracting standards similar to a wage-and-benefit parity policy. A complementary approach is to push for expansions in the earned income tax credits or wage subsidies. To take those $10 dollar an hour jobs and make them a bit more lucrative seems sensible.

Region: Thank you. I’ve learned so much today, and we’ve touched just a fraction of your work. I don’t know where you find the time to produce so much!

Katz: One thing is trying to leverage teams in research, which is a big trend in economics, a healthy trend. Most projects are not just done on your own; they involve a team of scholars working with large data sets, setting up the field experiment, collaborating with others.