This essay is also available on Medium.

On February 7, I published an essay, “Why I Voted to Hold Rates Steady,” which was a case study that explains the data I look at and framework I use to make my assessment of the appropriate stance of monetary policy. At the February 1 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, I voted with all of my colleagues to keep rates steady. Today I publish an update to that initial essay, using the same framework to explain why I again voted to keep rates steady at the FOMC meeting earlier this week. What is different now is that the rest of the FOMC voted in favor of an increase. I was alone in my dissent. I am not planning to publish an update after every meeting, but given that I reached a different conclusion than my colleagues, I thought it appropriate to provide an explanation.1

In summary, I dissented because the key data I look at to assess how close we are to meeting our dual mandate goals haven’t changed much at all since our prior meeting. We are still coming up short on our inflation target, and the job market continues to strengthen, suggesting that slack remains. Once the data do support a tightening of monetary policy, I would prefer the next policy move by the FOMC to be publishing a detailed plan that explains how and when we will begin to normalize our balance sheet. Once we put that plan in place, and we see the market reaction to it, we can return to using the federal funds rate to remove monetary accommodation when the data call for it.

My Analysis

Let me acknowledge up front that the analysis that follows is somewhat detailed and complex, yet it is still not comprehensive: FOMC participants look at a wider range of data than I capture in this piece. I am focusing on the data that I found most important in reaching my recent interest rate decision.

I always begin my analysis by assessing where we are in meeting the dual mandate Congress has given us: price stability and maximum employment.

Price Stability

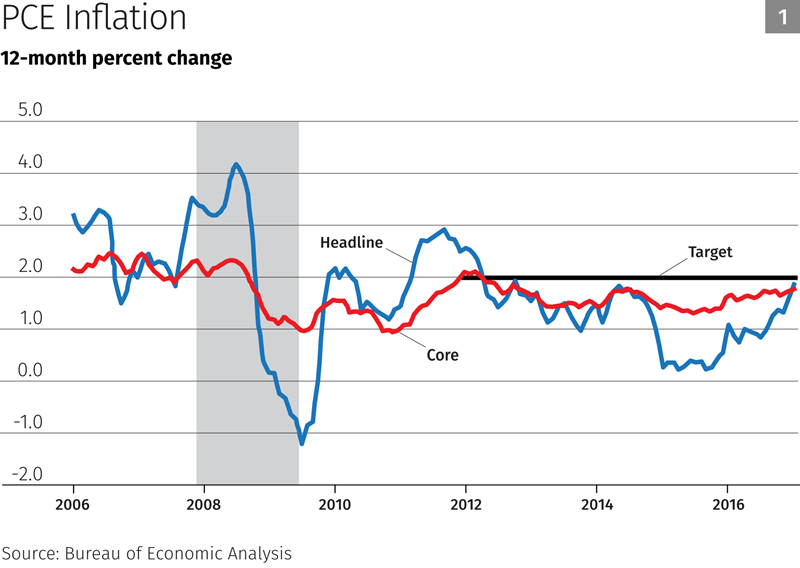

The FOMC has defined its price stability mandate as inflation of 2 percent, using the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) measurement. Importantly, we have said that 2 percent is a target, not a ceiling, so if we are under or over 2 percent, it should be equally concerning. We look at where inflation is heading, not just where it has been. Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, is one of the best predictors we have of future headline inflation, our ultimate goal. For that reason, I pay attention to the current readings of core inflation.

The following chart shows both headline and core inflation for the past 10 years. You can see that both have been below our 2 percent target for several years. Twelve-month core inflation is at 1.7 percent, and while it seems to be moving up somewhat, it is doing so slowly, if at all. It is still below target, and, importantly, even if it met or exceeded our target, 2.3 percent should not be any more concerning than the current reading of 1.7 percent, because our target is symmetric. Since the February FOMC meeting, we have received one new reading of PCE. While headline inflation has increased, it has done so largely because of higher energy prices, which we know are volatile and can be transitory. Core PCE did increase 0.3 percent in January on a monthly basis, but on a 12-month basis, my preferred measure, it has ticked up only ever so slightly, from 1.71 percent to 1.74 percent. My assessment of core inflation from the prior meeting is essentially unchanged.

While the FOMC wants to avoid making forecast errors whenever possible, to the extent that we make them, I would think we’d want our errors to be equally too high and too low. Yet, over the past five years, 100 percent of the medium-term inflation forecasts (midpoints) in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections have been too high: We keep predicting that inflation is around the corner. How can one explain the FOMC repeatedly making these one-sided errors? One-sided errors are indeed rational if the consequences are asymmetric. For example, if you are driving down the highway alongside a cliff, you will err by steering away from the cliff, because even one error in the other direction will cause you to fly over the cliff. In a monetary policy context, I believe the FOMC is doing the same thing: Based on our actions rather than our words, we are treating 2 percent as a ceiling rather than a target. I am not necessarily opposed to having an inflation ceiling. The European Central Bank has a 2 percent ceiling instead of a symmetric target. However, I am opposed to stating we have a target but then behaving as though it were a ceiling.

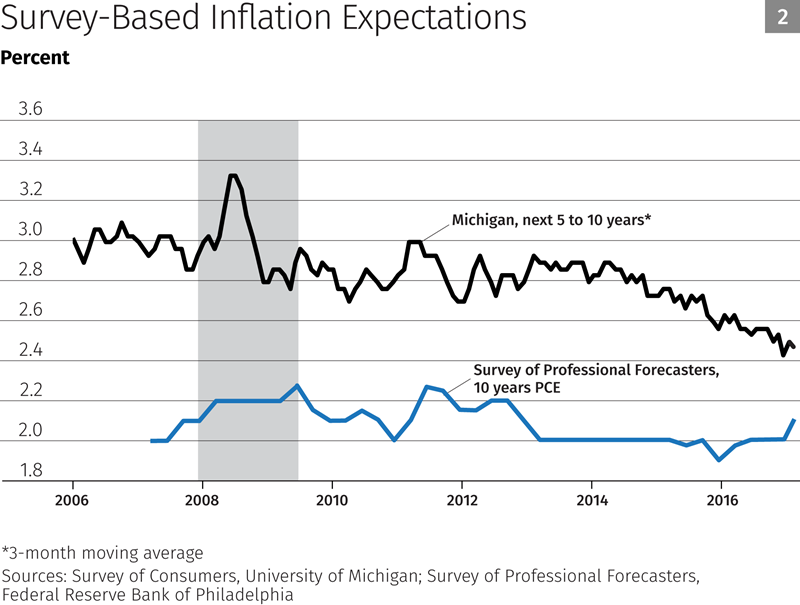

Next let’s look at inflation expectations—or where consumers and investors think inflation is likely headed. Inflation expectations are important drivers of future inflation, so it is critical that they remain anchored at our 2 percent target. Here the data are mixed. Survey measures of long-term inflation expectations are flat or trending down. (Note the Michigan survey, the black line, is always elevated relative to our 2 percent target. What is important is the trend, rather than the absolute level.) The Michigan survey has been trending down over the past few years and is now near its lowest-ever reading. In contrast, professional forecasters seem to remain confident that inflation will average 2 percent. While the professional forecast ticked up slightly, these readings are essentially unchanged since the last FOMC meeting.

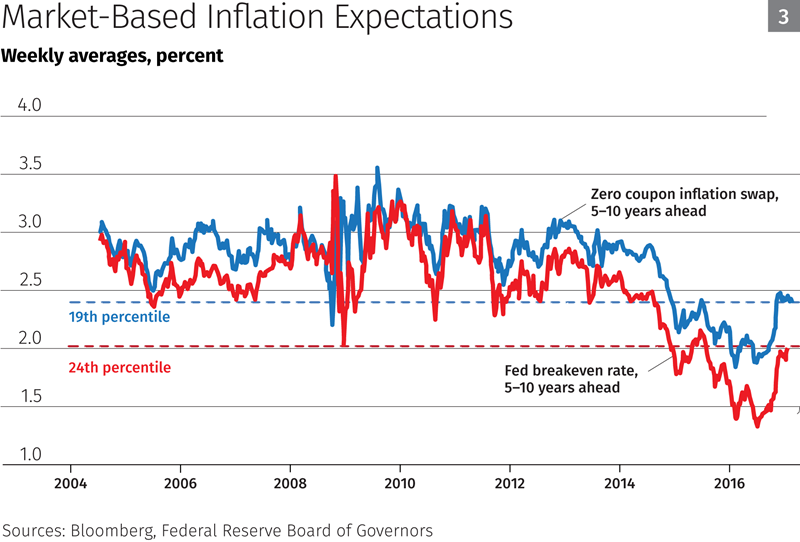

Market-based measures of long-term inflation expectations jumped a bit immediately after the election. I will write more about this later, but the financial markets are guessing about what fiscal and regulatory actions the new Congress and the Trump Administration will enact. We don’t know what those will be, so I don’t think we should put too much weight on these recent market moves yet. And, in any case, the markets’ inflation forecasts are still at the low end of their historical range. These readings are essentially unchanged since the last FOMC meeting.

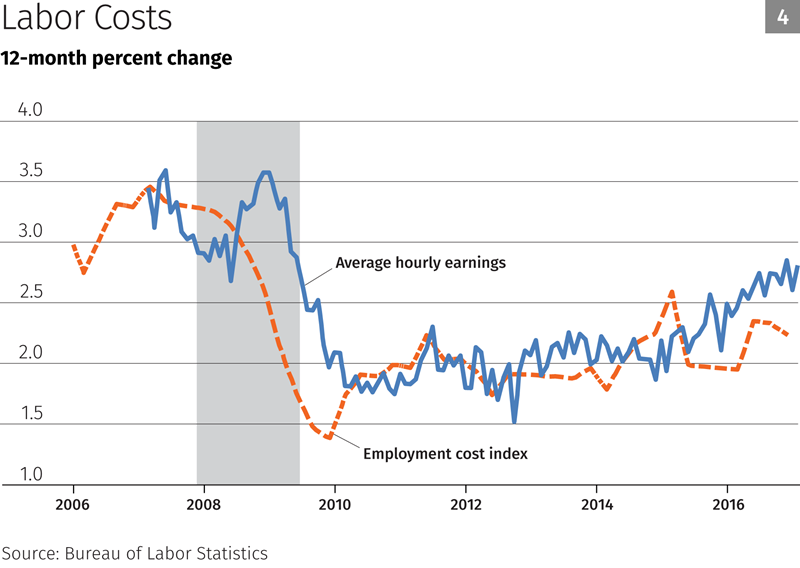

But perhaps inflationary pressures are building that we aren’t yet seeing in the data. I look at wages and costs of labor as potentially an early warning sign of inflation around the corner.2 If employers have to pay more to retain or hire workers, eventually they will have to pass those costs on to their customers. Eventually, those costs must show up as inflation. But we aren’t seeing a lot of movement in these data. The red line is the employment cost index, a measure of compensation that includes benefits and that adjusts for employment shifts among occupations and industries. It has been more or less flat over the past six years, and there has been no new information since the last FOMC meeting. The blue line is the average hourly earnings for employees. The growth rate of hourly earnings has increased somewhat in the past year, but fell slightly since the last FOMC meeting, and it is still low relative to the precrisis period. In short, the cost of labor isn’t showing signs of building inflationary pressures that are ready to take off and push inflation above the Fed’s target. And since the last FOMC meeting, overall, data on wage inflation are mixed.

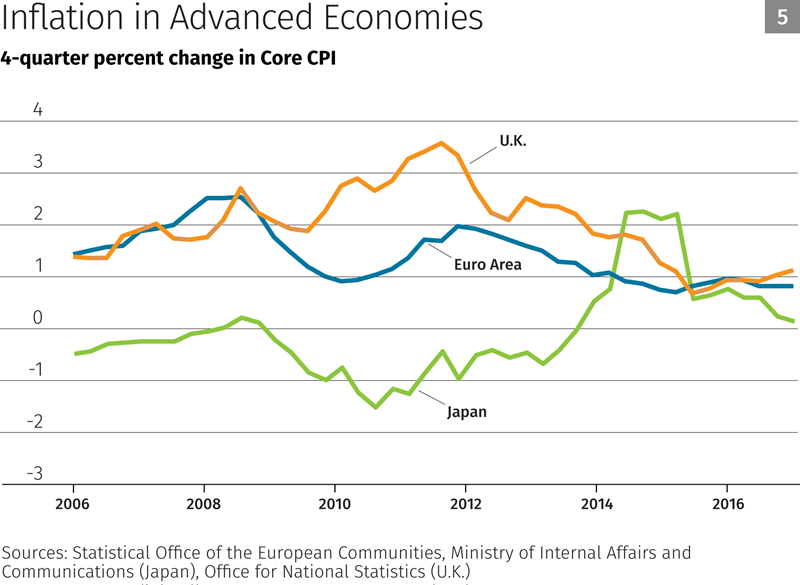

Now let’s look around the world. Most major advanced economies have been suffering from low inflation since the global financial crisis. It seems unlikely that the United States will experience a surge of inflation while the rest of the developed world suffers from low inflation. It is true that headline inflation rates have climbed around the world since the last FOMC meeting. As noted earlier, that is due to higher oil prices, which can be transitory. More importantly, core inflation rates in advanced economies continue to come in below their inflation targets.

In summary, inflation is still below our target. While there are some signs of inflation slowly building toward our target, it isn’t happening rapidly, and inflation expectations appear well-anchored. Not much has changed since the last FOMC meeting.

Maximum Employment

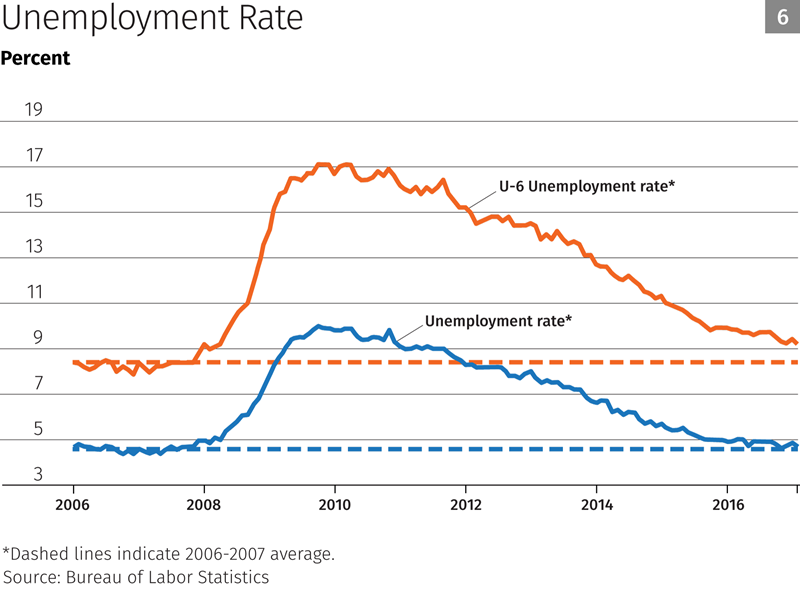

Next let’s look at our maximum employment mandate. One of the big questions I am wrestling with is whether the labor market has fully recovered or if there is still some slack in it. In the past year or so, some people have repeatedly declared that we have reached maximum employment and no further gains are possible without triggering higher inflation. And, repeatedly, the labor market has proven otherwise, the last month being only the latest example. The headline unemployment rate has fallen from a peak of 10 percent to 4.7 percent, roughly the level it was at before the financial crisis. But we know that measurement doesn’t include people who have given up looking for a job or are involuntarily stuck in a part-time job. So we also look at a broader measure of unemployment, what we call the U-6 measure, which includes those workers. The U-6 measure peaked at 17.1 percent in 2010 and has fallen to 9.2 percent today, which is still almost 1 percentage point above its precrisis level. The U-6 measure suggests that there may still be additional workers who might re-enter the labor force if the job market remains healthy.

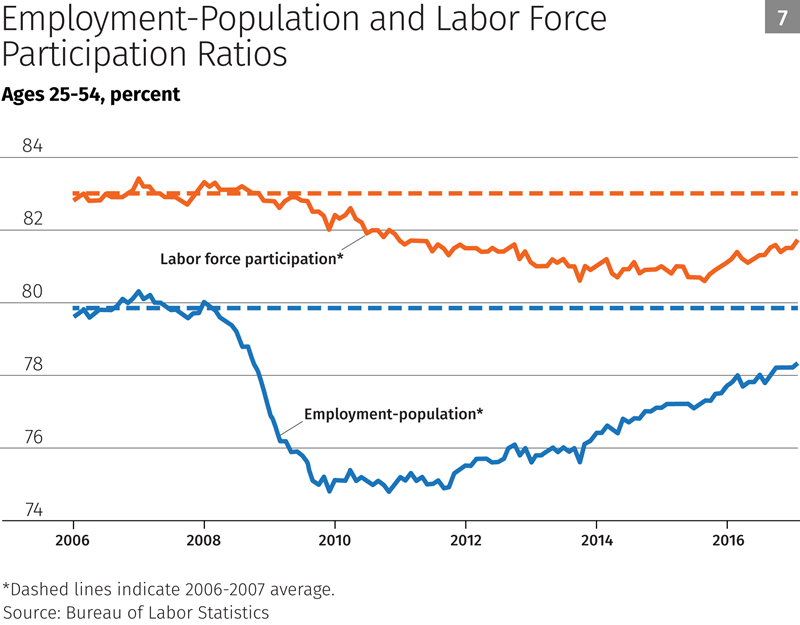

One of the big surprises over the past 18 months is how strong the job market has been (creating an average of 200,000 net jobs per month, which is much higher than the 80,000 to 120,000 jobs per month needed to keep up with (trend) labor force growth); yet the unemployment rate has remained fairly flat near 5 percent. This surprised us a bit because it suggests that there were many more people who were interested in working than historical patterns predicted. Some other measures we look at are the employment-to-population ratio and the labor force participation rate, which capture what percentage of adults are working or in the labor force. We know these are trending down over time due to the aging of our society (as more people retire, a smaller share of adults are in the labor force). To adjust for those trends, I prefer to look at these measures by focusing on prime working-age adults. The next chart shows that in both measures, there appears to be more labor market slack than before the crisis.

The bottom line is the job market has improved substantially, and we are approaching maximum employment. But we aren’t sure if we have yet reached it. We may not have. In 2012, the midpoint estimate among FOMC participants for the long-term unemployment rate was 5.6 percent—the FOMC’s best estimate for maximum employment. We now know that was too conservative—many more Americans wanted to work than we had expected. If the FOMC had declared victory when we reached 5.6 percent unemployment, many more workers would have been left on the sideline. Since the last FOMC meeting, the headline unemployment rate is unchanged at 4.7 percent. However, for the population 16 and older, labor force participation climbed from 62.7 percent to 63.0 percent and the employment-to-population ratio increased from 59.7 percent to 60.0 percent. The story of a growing labor force, either by workers re-entering or choosing not to leave, continues, without pushing inflation notably higher.

We also know that the aggregate national averages don’t highlight the serious challenges individual communities are experiencing. For example, today while the headline unemployment rate for all Americans is 4.7 percent, it is 8.1 percent for African Americans and 5.6 percent for Hispanics. The broader U-6 measure, mentioned above, is roughly double the headline rate for each group.

Current Rate Environment

OK, so we are still coming up somewhat short on our inflation mandate, and we may not have yet reached maximum employment. That suggests that somewhat accommodative monetary policy would still be appropriate to close those gaps. Let’s have a look at where we are now: Is current monetary policy accommodative, neutral or tight?

I look at a variety of measures, including rules of thumb such as the Taylor rule, to determine whether we are accommodative or not. There are many versions of such rules, and none are perfect.

One concept I find useful, although it requires a lot of judgment, is the notion of a neutral real interest rate, sometimes referred to as R*, which is the rate that neither stimulates nor restrains the economy. Many economists believe the neutral rate is not static, but rises and falls over time as a result of broader macroeconomic forces, such as population growth, demographics, technology development and trade, among others.

There is a range of estimates for the current neutral real rate. Having looked at them, I tend to think it is around zero today, or perhaps slightly negative. The FOMC raised rates by 0.25 percentage point in December, moving the target range for the nominal federal funds rate to 0.50 percent and 0.75 percent. With core inflation around 1.7 percent, that suggests that the target range for the real federal funds rate was between -1.2 percent and -0.95 percent. Combined with a neutral rate of zero, that means monetary policy was about 100 basis points, or 1 percent, accommodative going into this week’s FOMC meeting. Monetary policy has been at least this accommodative for several years, including the effects of the Federal Reserve’s expanded balance sheet, without triggering a rapid tightening of the labor market or a sudden increase in inflation. This suggests that monetary policy has been only moderately accommodative over this period. This level of accommodation seemed appropriate given where we are relative to our dual mandate.

Financial Stability Concerns

The FOMC should always keep its eyes open for financial stability concerns both in the near term and over the long term. Whether monetary policy is the right tool to address any concerns is a different matter for another time. At the moment, although stock prices, housing prices and especially some commercial real estate prices appear somewhat elevated, they do not appear to pose an immediate financial stability risk. Yes, stock prices have risen further since the last FOMC meeting. But our job is not to keep the stock market from climbing or from falling. The key question is, will a market correction trigger economic instability? It will cause pain for investors, but the likelihood of a correction triggering a financial crisis is low. While houses can be levered 5 to 1 or higher, stock market investors generally have far less leverage. The much lower leverage supporting equity investments should reduce the contagion risk if markets correct. I will return to the issue of the intersection between monetary policy, public markets and financial stability in a future essay. Over the long term, I continue to be very concerned about the systemic risks posed by the largest banks. Monetary policy most certainly cannot address the too-big-to-fail risk.

Fiscal Outlook

I mentioned earlier that financial markets (both the stock and bond markets) seem to be pricing in some form of fiscal stimulus, perhaps tax cuts and/or increased spending, and perhaps a reduction in regulations from the new Administration and the new Congress. Those developments could be important to overall economic growth and, by extension, to the future path of monetary policy. But we have little information about what those new policies will actually be, what their magnitude will be and when they would take effect. Markets are guessing. Financial markets are good at some things, but, in my view, notoriously bad at forecasting political outcomes. They didn’t forecast Brexit. They didn’t forecast the results of the U.S. presidential election. I don’t have much confidence in their ability to forecast fiscal policy given how little we know today. So I am not yet incorporating the markets’ guesses about fiscal policy changes into my outlook for the economy.

Global Environment

The world is large and complex. There is virtually always something concerning going on somewhere. But, overall, global economic and geopolitical risks do not seem more elevated than they have been in recent years. Yes, the details of Brexit still need to be worked out. The future of global trading relationships is also uncertain. The world economy is expected to grow at 3.1 percent in 2017. Developing economies are expected to grow at 4.5 percent and advanced economies at 1.9 percent.3 The dollar has increased more than 20 percent over the past 2½ years. The strong dollar will likely continue to put some downward pressure on inflation. Overall, the global environment doesn’t seem to be sending a strong signal for a change in U.S. interest rates.

Risk Management

The FOMC has extraordinarily powerful tools to deal with a surprise burst of inflation. We can always raise rates, quickly and aggressively if need be. And my view is that there is strong commitment among FOMC participants to maintaining our 2 percent inflation target. However, the closer we are to the zero lower bound, the fewer tools we have to deal with a surprise of low inflation or economic weakness. From a risk management perspective, that suggests, if we are to err, it is better to err on the side of being more accommodative than being more restrictive.

Policy Tools

Adjusting the federal funds rate is the primary policy tool for the FOMC to ease or tighten monetary conditions. However, as a result of the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing programs, we have an expanded balance sheet of approximately $4.5 trillion. I do not believe adjusting the balance sheet should be a regular policy tool. Instead, I believe we should begin the normalization process soon. The first step to normalizing the balance sheet, in my view, is to publish a detailed plan of how exactly we will shrink the balance sheet and when that roll-off will begin. I think it is imperative that we give the markets time to understand the details of the plan before it is implemented. And while it is likely the announcement of that plan will not trigger much of a market response, we don’t know that for certain. The announcement of our balance sheet plan could trigger somewhat tighter monetary conditions. In that case, that announcement could be viewed as a substitute for a federal funds rate increase, whose magnitude is uncertain. Once data support tightening monetary policy, I would prefer that the FOMC publish its plan for the balance sheet. After it has been published and the market response is understood, we can return to using the federal funds rate as our primary policy tool, with the balance sheet normalization under way in the background.

What Might Be Wrong?

What might my analysis be missing? Some economic or financial shock could hit us, from within the U.S. economy or from outside. That is always true, and we need to be ready to respond if necessary. In addition, if we are surprised by higher inflation than we currently expect, we might need to raise rates more aggressively. Some argue that gradual rate increases are better than waiting and having to move aggressively. It isn’t clear to me that one path is obviously better than the other.

Some others argue that there may be nonlinearity in the inflationary process and that as inflation crosses the 2 percent threshold, it might suddenly accelerate. I see no evidence of this, especially considering that inflation expectations are well-anchored. Historically, U.S. inflation expectations have moved slowly, generally making large changes only in response to persistent changes in inflation trends. As long as the FOMC remains committed to acting decisively to defend against sustained deviations from our 2 percent target, I see the risk of a sudden change in inflation expectations as low.

One additional consideration that I think about is the possibility that low rates are scaring people and causing them to save more and invest less, while conventional wisdom is that low rates should lead to more investment and less saving. It is not a crazy argument because negative rates seem to be having unexpected results in some countries that have adopted them. If negative rates can scare people into saving more, perhaps very low rates can too? This would be an argument to raise rates just so people can feel more confident. However, it is hard for me to see how high rates by themselves can lead to more confidence, more spending and more investment. Take Japan: Should the Bank of Japan increase rates dramatically to send a confident signal? Does anyone think that would work in jump-starting Japan’s economy? I doubt it. A signal of confidence from higher rates must be coupled with strong underlying economic fundamentals. When the data indicate that we are approaching our dual mandate targets, I do believe markets will take some confidence from our rate increases because those higher rates will reflect strong economic fundamentals. I don’t find a strategy of raising rates purely as a psychological tool a compelling argument.

Conclusion

As was the case in the February FOMC meeting, we are still coming up somewhat short on our inflation mandate, and we may not have yet reached maximum employment. Inflation expectations remain well-anchored. Monetary policy is currently somewhat accommodative. There don’t appear to be urgent financial stability risks at the moment. There is great uncertainty about the fiscal outlook. The global environment seems to have a fairly typical level of risk. From a risk management perspective, we have stronger tools to deal with high inflation than low inflation. Looking at all this together led me to vote against a rate increase.

Endnotes

1 The views I express here are my own and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve System.

2 The truth is there is not much of a correlation between high wage growth and future inflation but, intuitively, they must be linked.

3 See the International Monetary Fund’s January 2017 World Economic Outlook Update.