This essay is also available on Medium.

Last week, the Federal Open Market Committee raised interest rates for the third time this year and, also for the third time this year, I voted against that increase. I initially dissented in March because I didn’t see much evidence that inflation was climbing toward the Fed’s 2 percent target and there still seemed to be slack in the labor market. I didn’t see the need to tighten monetary policy. Since then, instead of rising, inflation has actually fallen to 1.6 percent. Now a new concern is emerging: In response to our rate hikes, the yield curve has flattened significantly, potentially signaling an increasing risk of a recession. Together, these factors make a compelling case that the FOMC should not increase rates further until we are much more confident that inflation is returning to our target.

Congress has given the Fed its dual mandate of price stability, which we define as 2 percent inflation, and maximum employment, which essentially means that as many Americans who want to work are able to find jobs. Typically, we believe those two goals are linked through wages: As the job market gets stronger, businesses compete to find workers, driving wages higher, which then drives up inflation. When inflation climbs above the Fed’s target, the FOMC raises interest rates, which slows economic activity, wage growth and inflation. We cut rates to do the opposite. At least that how it’s supposed to work.

The past couple of years have been perplexing for the Fed because even though the job market has strengthened a lot, with the headline unemployment rate falling from a peak of 10 percent in 2009 to 4.1 percent today, wage growth and inflation have been muted. Why aren’t wages picking up?

In my view, the two most likely explanations are that the job market is not as tight as the 4.1 percent unemployment rate suggests and that people’s expectations for future inflation have fallen, which can become self-fulfilling.

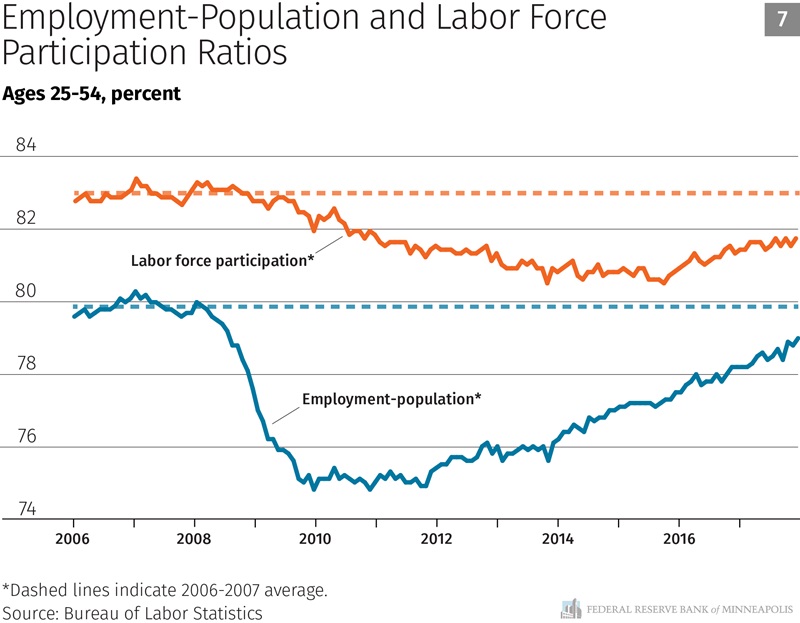

The headline unemployment rate includes only people who are actively looking for work. While 4.1 percent is low by historical standards, the Great Recession pushed many people out of the labor force, some of whom are only slowly reentering. One measure of the labor force—the participation rate for workers between 25 and 54 years old, typically called “prime age”—suggests that there could be more than a million workers still on the sidelines. We don’t know how many will return, but with wage growth still well below its precrisis pace, it’s easy to argue that we might not really be at full employment. If wage growth climbs, I expect to see more people come into the labor force.

Turning to expectations, people’s beliefs about future inflation are enormously important to where inflation is actually headed. If workers believe inflation will be low in the future, they demand smaller wage increases from their employers. Japan has shown us that when low inflation expectations become embedded in a society, they can be very hard to raise. While high inflation is clearly bad for society, excessively low inflation can limit the Fed’s ability to respond to future recessions, potentially making them longer and more damaging. Market-based measures suggest that U.S. inflation expectations have fallen well below precrisis levels.

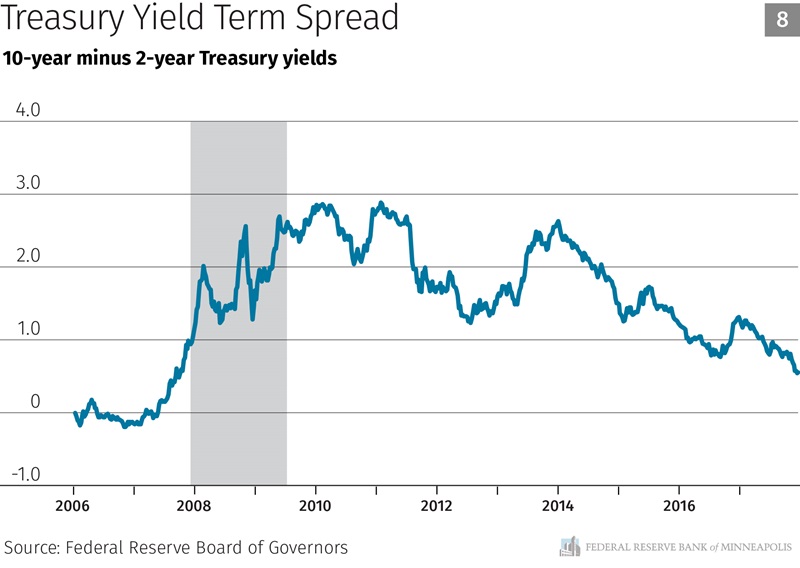

These arguments drove me to vote against rate increases in March and June, and the data since those votes have only heightened my concerns. What is new is the flattening yield curve, the difference between 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields, which has fallen from around 1.45 percent before the FOMC started raising rates in late 2015, to approximately 0.51 percent today. An inverted yield curve, where short rates are above long rates, is one of the best signals we have of elevated recession risk and has preceded every single recession in the past 50 years. While the yield curve has not yet inverted, the bond market is telling us that the odds of a recession are increasing and that inflation and interest rates will likely be low in the future. These signals should caution the FOMC against further rate increases until it becomes clear that inflation is actually picking up.

These trends suggest that monetary policy is entering a delicate phase. We all want the economic expansion to continue. However, continuing to raise rates in the absence of increasing inflation could needlessly hold down wage growth while potentially increasing the chance of a recession.

My Analysis (An Update to the Framework First Published in February 2017)

Let me acknowledge up front that the analysis that follows is somewhat detailed and complex; yet it is still not comprehensive. FOMC participants look at a wider range of data than I detail here. I am focusing only on the data that I find most important to determining the appropriate stance of monetary policy.

As I have done previously, let me begin my analysis by assessing our progress in meeting the dual mandate Congress has given us: price stability and maximum employment.

Price Stability

The FOMC has defined its price stability mandate as inflation of 2 percent, using the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) measurement. Importantly, we have said that 2 percent is a target, not a ceiling, so if we are under or over 2 percent, it should be of equal concern. We look at where inflation is heading, not just where it has been. Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, is one of the best predictors we have of future headline inflation, our ultimate goal. For that reason, I pay attention to the current readings of core inflation.

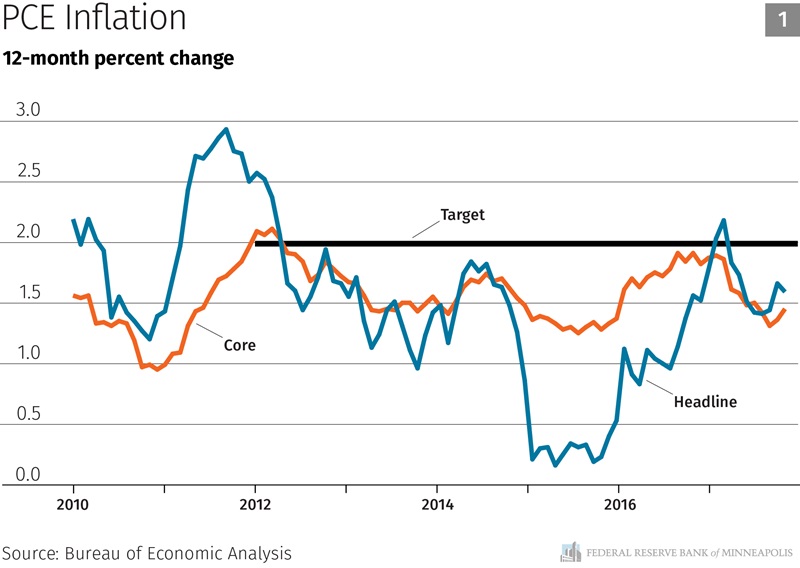

Chart 1 shows both headline and core inflation since 2010. The rebound in energy prices lifted headline inflation earlier this year, but it has since moved back down below 2 percent. You can see that both inflation measures have been below our 2 percent target for several years. Twelve-month core inflation has fallen below 1.5 percent in recent months and shows no sign of consistently trending upward. It is still below target and, importantly, even if it met or exceeded our target, 2.6 percent should not be of any more concern than the current reading of 1.4 percent, because our target is symmetric. Since the June FOMC meeting, when the Committee last raised the target range for the federal funds rate, both headline and core inflation have declined further below 2 percent. Headline inflation has fallen from 1.7 percent to 1.6 percent, while core inflation has dropped from 1.6 percent to 1.4 percent. This is concerning. Some have attributed the low core inflation readings to transitory factors such as a drop in cell phone service prices. That is possible, but I need to see more data before I am convinced that inflation declines are only transitory.

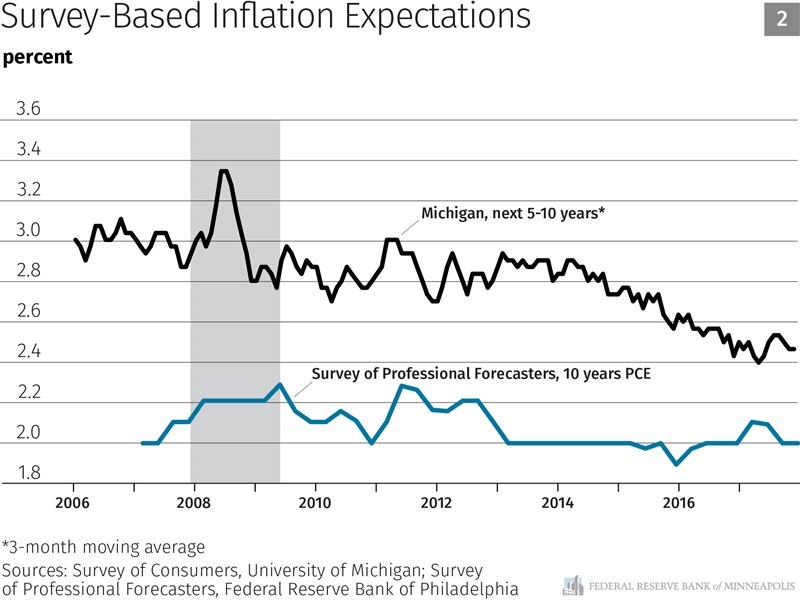

Next let’s look at inflation expectations—or where consumers and investors think inflation is likely headed (Chart 2). Inflation expectations are important drivers of future inflation, so it is critical that they remain anchored at our 2 percent target. Here the data are mixed. Survey measures of long-term inflation expectations are flat or trending downward. (Note that the Michigan survey, the black line, is consistently elevated relative to our 2 percent target. What is important is the trend, rather than the absolute level.) The Michigan survey has found inflation expectations trending downward over the past few years, and they remain near their lowest-ever reading. In contrast, professional forecasters seem to remain confident that inflation will average 2 percent. While the professional forecast ticked upward slightly earlier this year, those readings have ticked back down again since the June FOMC meeting.

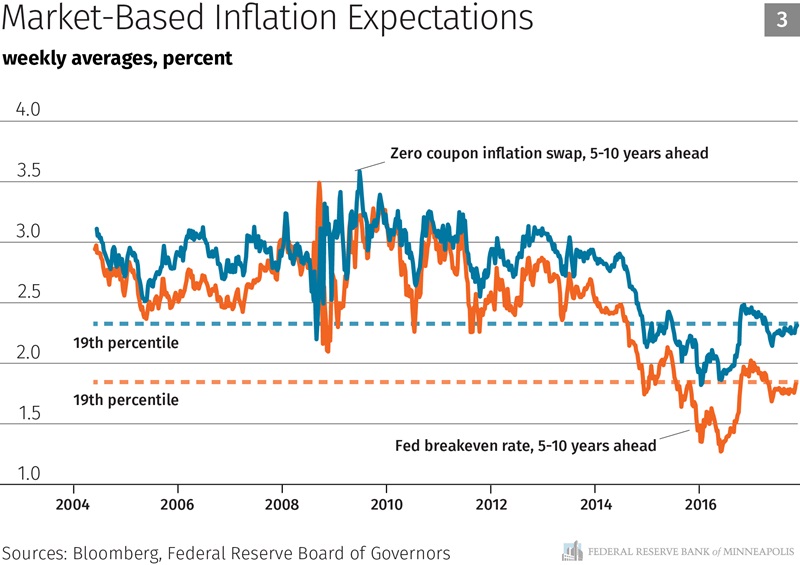

Market-based measures of long-term inflation expectations jumped a bit immediately after the 2016 presidential election. The markets’ inflation forecasts moved back down earlier this year and have edged up slightly since the June meeting. As Chart 3 indicates, market-based expectations remain at the low end of their historical range.

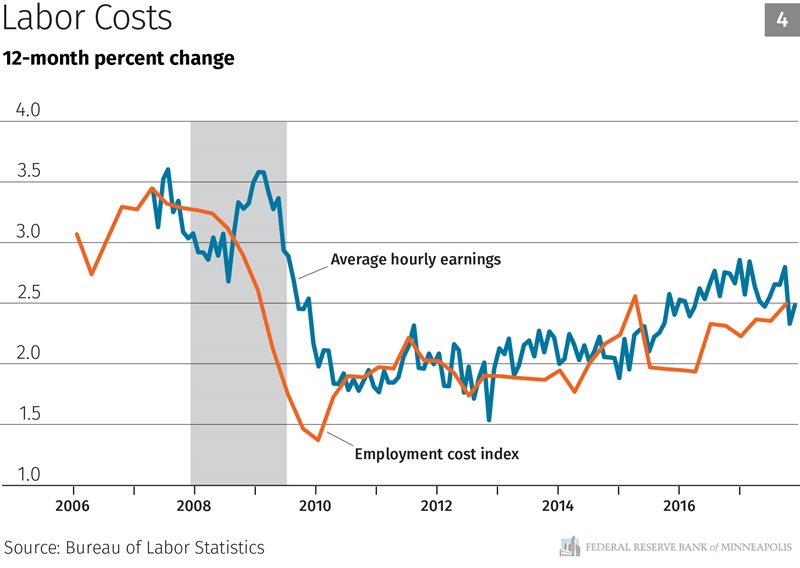

But perhaps inflationary pressures are building that we aren’t yet seeing in the data. I look at wages and costs of labor as potentially early warning signs of inflation around the corner.1 If employers have to pay more to retain or hire workers, eventually they will have to pass those costs on to their customers. Ultimately, those costs must show up as inflation. But we aren’t seeing a lot of movement in these data. The red line in Chart 4 is the employment cost index, a measure of compensation that includes benefits and is adjusted for employment shifts among occupations and industries. The blue line is the average hourly earnings for employees. Both lines have moved little since the June FOMC meeting, and each stands at 2.5 percent; both remain low relative to the precrisis period. In short, the cost of labor isn’t showing signs of building inflationary pressures that are ready to take off and push inflation above the Fed’s target.

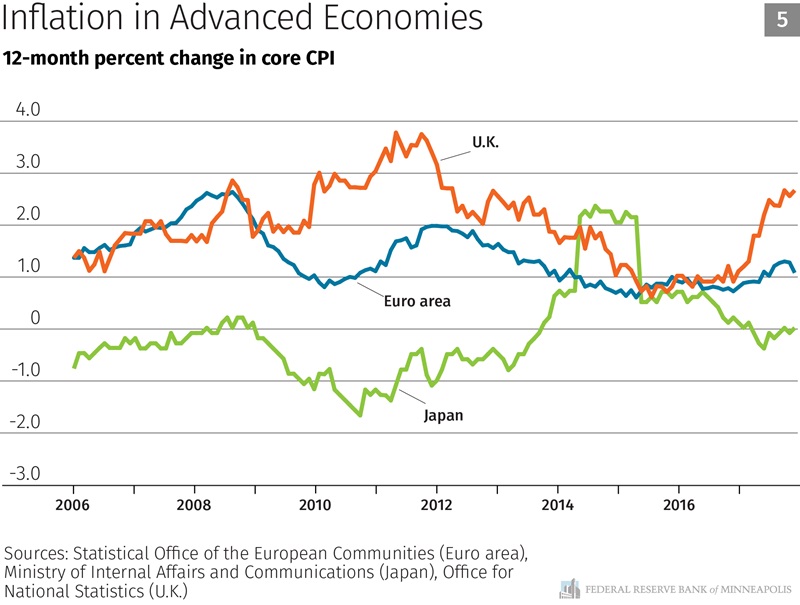

Now let’s look around the world. Most major advanced economies have been suffering from low inflation since the global financial crisis. It seems unlikely that the United States will experience a surge of inflation while the rest of the developed world suffers from low inflation. Since the June FOMC meeting, headline inflation has increased in the United Kingdom due to last year’s sterling depreciation resulting from Brexit, but headline inflation has been roughly flat in other advanced economies. As you can see in Chart 5, with the exception of the U.K., core inflation rates in advanced economies continue to come in below their target rates.

In summary, inflation has moved further below our target, and market-based measures of inflation expectations remain at low levels. Some argue that the decline in inflation this year is transitory, but we don’t know that for certain, and the longer it persists, the more tenuous the transitory factors story becomes.

Maximum Employment

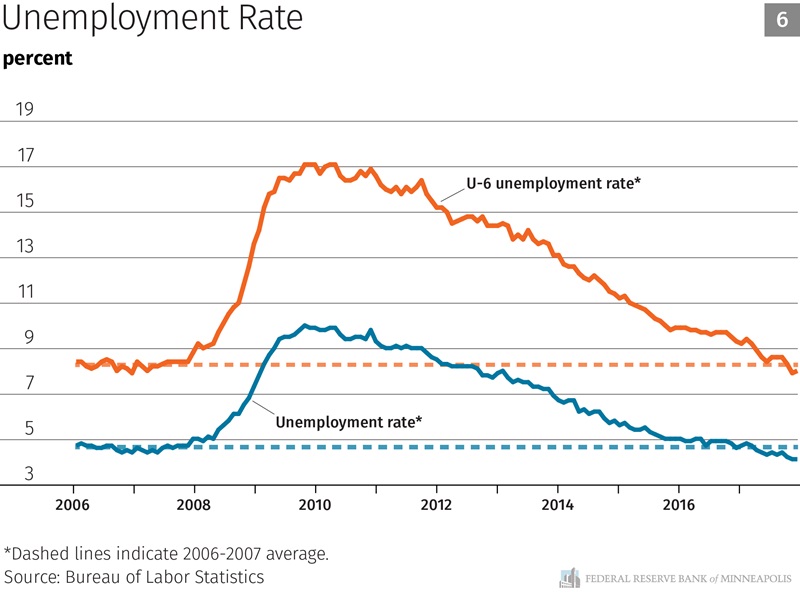

Next let’s look at our maximum employment mandate. One of the big questions I continue to wrestle with is whether the labor market has fully recovered or if there is still some slack in it. Over the past few years, some people repeatedly declared that we had reached maximum employment and that no further gains were possible without triggering higher inflation. And, repeatedly, the labor market proved otherwise. Chart 6 shows that the headline unemployment rate has fallen from a peak of 10 percent to 4.1 percent, below its precrisis level. We also look at a broader measure of unemployment, what we call the U-6 measure, which includes people who have given up looking for a job or are involuntarily stuck in a part-time job. The U-6 measure peaked at 17.1 percent in 2010 and has fallen to 8.0 percent today, also below its precrisis level. But these measures still leave out a large number of people who might prefer to work if better job opportunities were available to them.

The employment-to-population ratio and the labor force participation rate capture the percentage of adults working or actively looking for work. We know these are trending downward over time due to the aging of our society (as more people retire, a smaller share of adults are in the labor force). To adjust for those trends, I prefer to look at these measures by focusing on prime working-age adults. Chart 7 shows that, even with the strong job gains in recent years and the decline in unemployment rates, the labor market still shows more slack than before the crisis.

The bottom line is that the job market has improved substantially, and we are getting closer to maximum employment. But we still aren’t sure if we have yet reached it. In 2012, the midpoint estimate among FOMC participants for the long-term unemployment rate was 5.6 percent—the FOMC’s best estimate for maximum employment. We now know that was too conservative—many more Americans wanted to work than we had expected. If the FOMC had declared victory when we reached 5.6 percent unemployment, many more workers would have been left on the sidelines. Since the June FOMC meeting, the headline unemployment rate has fallen from 4.3 percent to 4.1 percent. The labor force participation rate for prime working-age adults increased from 81.5 percent to 81.8 percent, while the prime-age employment-population ratio increased notably from 78.4 to 79.0 percent.

We also know that the aggregate national averages don’t highlight the serious challenges individual communities are experiencing. For example, while the headline unemployment rate today for all Americans is 4.1 percent, it is still 7.3 percent for African Americans and 4.7 percent for Hispanics. The broader U-6 measure, mentioned above, is roughly double the headline rate for each group.

Current Rate Environment

OK, so we are still coming up short on our inflation mandate, and we are closer to reaching maximum employment. Let’s have a look at where we are now: Is current monetary policy accommodative, neutral or tight?

I look at a variety of measures, including rules of thumb such as the Taylor rule, to determine whether we are accommodative or not. There are many versions of such rules, and none are perfect.

One concept I find useful, although it requires a lot of judgment, is the notion of a neutral real interest rate, sometimes referred to as R*, which is the rate that neither stimulates nor restrains the economy. Many economists believe the neutral rate is not static, but rises and falls over time as a result of broader macroeconomic forces, such as population growth, demographics, technology development and trade, among others.

There are a range of estimates for the current neutral real rate. Having looked at them, I tend to think it is around zero today, or perhaps slightly negative. The FOMC raised rates by 0.25 percent in June, moving the target range for the nominal federal funds rate to between 1.00 percent and 1.25 percent. With core inflation around 1.5 percent, the real federal funds rate was between -0.50 percent and -0.25 percent. Combined with a neutral rate of zero, that means monetary policy was only about 25 to 50 basis points, or 0.25 percent to .50 percent, accommodative going into last week’s FOMC meeting. Monetary policy has been at least this accommodative for several years, including the effects of the Federal Reserve’s expanded balance sheet, without triggering increasing inflation. This further confirms my view that monetary policy has been only moderately accommodative over this period.

Financial Stability Concerns

Please see my essay on how I think about monetary policy and financial stability.2 In short, while some asset prices appear elevated, I don’t see a correction as being likely to trigger financial instability. Investors would face losses from a stock market correction, but it’s not the Fed’s job to protect investors from losses. Our jobs are to achieve our dual mandate and to promote financial stability.

Fiscal Outlook

I had not factored major fiscal policy changes into my economic and policy forecasts because there was too much uncertainty as to whether, when and how large any fiscal changes would be. But given that the House and Senate have both passed major pieces of tax legislation, I have now incorporated the tax package into my economic forecast. The expected effects on supply and demand do not appear large enough at this point to change my expected path for monetary policy. If the economic effects end up larger than expected, I will adjust my policy forecast when that becomes clear.

Global Environment

The world is large and complex. There is always something distressing going on somewhere. But, overall, global economic and geopolitical risks do not seem more elevated than they have been in recent years. In fact, some global risks appear to have diminished, and the outlook for global growth is somewhat stronger than it was earlier in the year. The world economy is expected to grow at 3.6 percent in 2017 and 3.7 percent in 2018. Developing economies are expected to grow at 4.6 percent and 4.9 percent, respectively, while advanced economies increase at 2.2 and 2.0 percent rates.3 Overall, the global environment doesn’t seem to be sending a strong signal for a change in U.S. interest rates.

Flattening Yield Curve

The yield curve term spread, the difference between 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields, has fallen from around 1.45 percent before the FOMC started raising rates in late 2015, to approximately 0.51 percent today (Chart 8). This flattening of the yield curve is an important new development this year. An inverted yield curve, where short rates are above long rates, is one of the best signals we have of elevated recession risk and has preceded every single recession in the past 50 years.

I believe the FOMC’s rate increases are directly affecting the yield curve: As the FOMC has raised rates, the front end of the curve is moving up with our policy moves, which is to be expected. But because the Committee has been raising rates in a low inflation environment, we are sending a hawkish signal, which is likely holding down the long end of the curve by depressing inflation expectations.

The yield curve may also be reflecting the market pricing in a lower long-term neutral rate (R*) environment. Whether the markets are signaling a lower R* or lower long-term inflation expectations, these signals should offer caution about future federal funds rate increases, unless inflation picks up.

Policy Tools

The FOMC announced its plan to begin rolling off its balance sheet in the September meeting, which actually went into effect in October. That roll-off plan is operating as expected, in the background. I supported taking that action.

What Might Be Wrong?

What might my analysis be missing? Some economic or financial shock could hit us, from within the U.S. economy or from outside. That is always true, and we need to be ready to respond if necessary. In addition, if we are surprised by higher inflation than we currently expect, we might need to raise rates more aggressively. Some argue that gradual rate increases are better than waiting and having to move aggressively. It isn’t clear to me that one path is obviously better than the other.

Conclusion

The labor market has tightened since we raised rates in June, but inflation is not rising. It doesn’t appear that we are sustainably moving closer to our inflation target. Inflation expectations are low and may have already fallen. Monetary policy is currently only somewhat accommodative. There don’t appear to be urgent financial stability risks at the moment. The global environment seems to have a fairly typical level of risk. One new development is the flattening yield curve, which is also urging caution. From a risk management perspective, we have stronger tools to deal with high inflation than low inflation. Looking at all of these factors together led me to vote against a rate increase.

Endnotes

1 The truth is there is not much of a correlation between high wage growth and future inflation but, intuitively, they must be linked.

2 See Monetary Policy and Bubbles.

3 See the International Monetary Fund’s October 2017 World Economic Outlook.