It seems as though Minnesota farmers have entered a “new normal” of low profits after a period of extreme profits from 2007 through 2012. During that time, it appeared as if all farm decisions were correct and profits were almost automatic. Ag lenders, too, found themselves doing well, growing their ag portfolios and helping farms succeed. The tide has certainly turned, however, and farms have now experienced six years of low earnings.

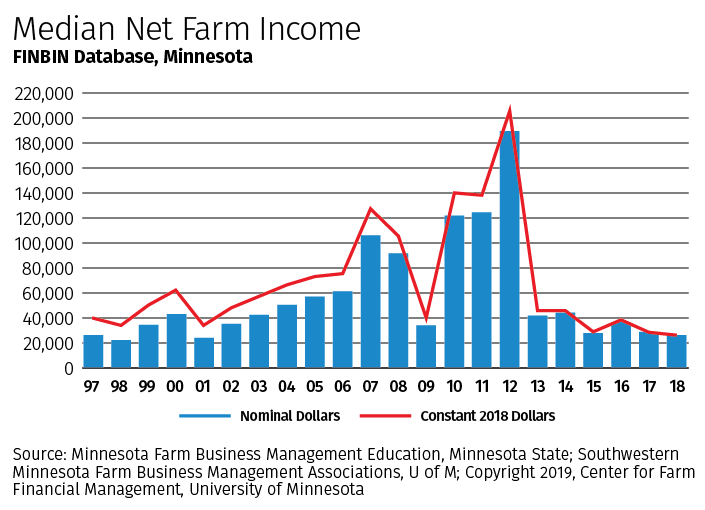

The FINBIN database,1 managed by the Center for Farm Financial Management at the University of Minnesota, helps keep tabs on the status of Minnesota agriculture. On an inflation-adjusted basis, 2018 was the lowest-income year for these farms in the 22 years of maintaining the database. While data used for this article are from Minnesota farms, low commodity prices and profitability challenges have had a similar impact on crop farmers in other states. This low income added to farmers’ financial stress and further impaired financial standings. Weather and trade are only two examples of the hurdles farmers faced in 2018.

As shown in the chart, the median farm earned only $26,055 in 2018. While comparable historical data are not available, the mid-1980s were likely a period with similarly low incomes. Note that Minnesota agriculture has also gone through considerable consolidation since the late 1990s, resulting in larger farms today. Minnesota farms control more than 2.5 times the assets they controlled two decades ago (in inflation-adjusted dollars). This larger nvestment, coupled with marginal earnings, equals greater risk for today’s farms, especially those with more debt.

Where is the risk?

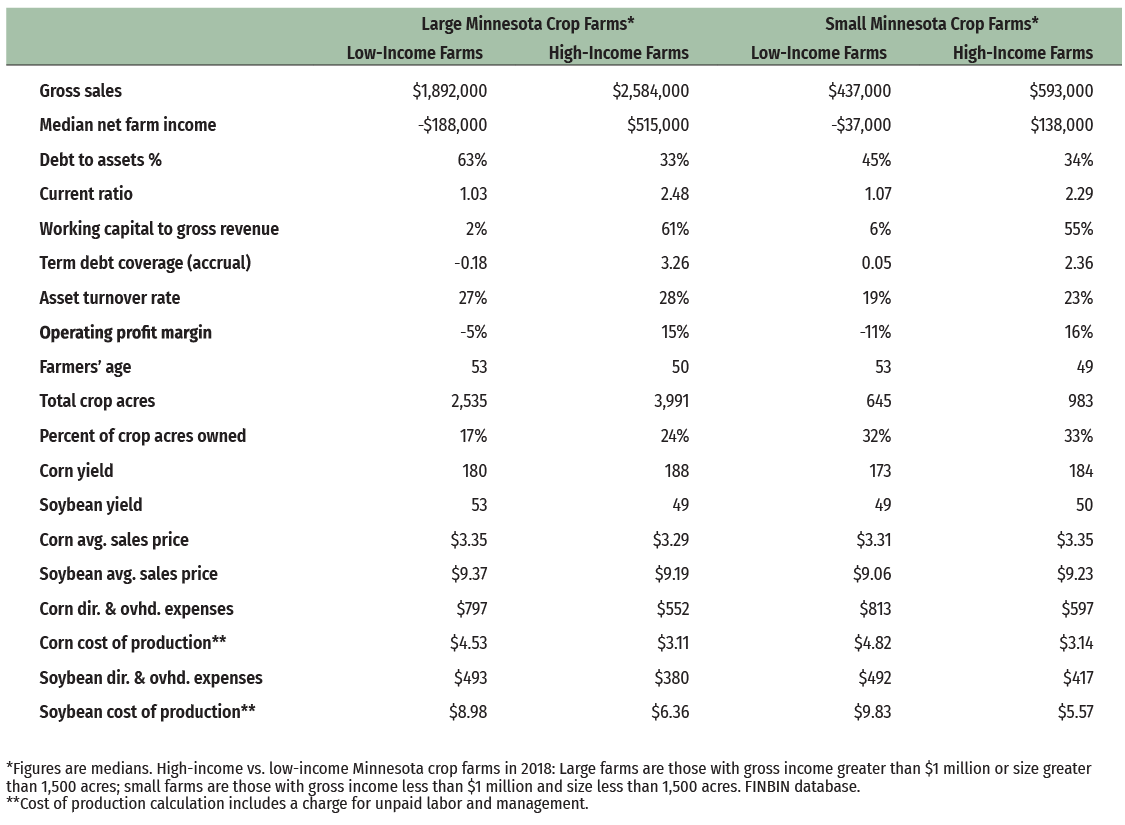

Currently, risk is evident throughout traditional agricultural commodities. One specific group experiencing significant risk in Minnesota is large crop farms. In any given year, there is a large difference between the least and most profitable farms. While a similar trend is recognized for small farms, it can be more surprising to see this significant performance gap between large producers. During profitable years, size and scale are advantages, and more volume leads to more profits. However, during periods of low profitability, size and scale can be a hindrance, especially if growth was financed with debt. If a farm is producing at a loss, being bigger only leads to a larger loss. Unfortunately, this is the situation for some large crop farms. In the table below, notice the two ends of this spectrum in 2018. Some farms, both large and small, are weathering today’s storm quite well, and others are facing great challenges.

The table shows the characteristics of cropping operations, sorted by the high-profit 20 percent and low-profit 20 percent. While the performance of the high-profit groups may be remarkable in this operating environment, it is important to focus on the risk associated with the low-profit groups. The low-profit groups have used nearly all of their working capital. Limited profits, liquidity, and repayment capacity have taken a toll on these farms. If the downturn continues, this group is extremely vulnerable and has few options.

As shown in the table, yields were similar for both groups, as was the asset turnover rate. Therefore, both are good producers; the difference seems to come from variances in debt levels and cost control. What is the key to success for the high-profit farms? Debt-to-asset ratios are higher for low-income small farms compared with more-profitable small farms, but the disparity between high- and low-income large farms is more significant. As a result, large farms with higher debt levels now have greater debt expense and are less resilient in the current environment of low commodity prices.

Cost control also affects profitability. A management advantage is apparent in the operating profit margin of the high-profit groups. The low-profit farms did a better job marketing their corn and soybean crops in 2018. However, looking specifically at direct and overhead expenses related to corn and soybean production, the high-profit groups managed costs better overall. Small savings in many expense categories make an impact. Again, volume is either a friend or a foe for these producers.

Weathering the storm

Most lenders will have borrowers in both profitability groups. It isn’t readily apparent as you drive down a road which group a producer falls into. Many farm operations have had financial setbacks in recent years. This is normal and expected during challenging times. This is why producers build working capital reserves—to weather those occasional storms. Appearances are deceiving, and it is important for all banks lending to farm borrowers to be diligent in their credit analysis to fully understand a farm’s financial position so that lenders can work effectively with both high- and low-profit farms. Thorough credit monitoring is crucial, with consideration given to:

- Analyzing debt coverage using accrualadjusted income, not just on a cash basis.

- Working with high-debt borrowers to reduce debt.

- Measuring earned net worth change, not just total net worth change.

- Evaluating the ratio of working capital to gross revenue, thus giving consideration to operational size.

- Preparing cash flow projections on a monthly basis to better match the timing of cash and operating loans, and carefully monitoring a borrower’s cost control management.

- Monitoring farm performance during the year. Consider budget to actual cash flow reporting and completion of interim balance sheets.

Many of these credit tasks are second nature for lenders. If they are not, consider credit policies and what analysis is missing in order to ensure farmers’ ability to weather the current farm financial storm. In the process, encourage borrowers to be astute managers. While there is no silver bullet to ensure profitability in today’s challenging environment, be sure to recognize the risk and who may be most susceptible. This is an important first step in the analysis process. Bigger doesn’t always mean better.

Endnotes

1 The 2,300 farms that participate in Minnesota farm business management education programs and contribute to this database represent over 10 percent of commercial farms in the state.