The importance of a reliable Internet connection became painfully apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as public health measures necessitated virtual education, work, and social interaction. Unfortunately, reliable Internet access is not a given for many households in Indian Country. This matters for economic development: the lack of dependable Internet access constrains business growth in tribal areas. Moreover, the underdevelopment of broadband1 has discouraged the return of young, highly educated individuals to tribal areas—in other words, it has worsened the “brain drain” in Indian Country.2

In our new Center for Indian Country Development working paper, The Tribal Digital Divide: Extent and Explanations, we provide the first comprehensive assessment of the tribal digital divide and its determinants. After accounting for differences in a host of factors that predict broadband deployment, we find that households in tribal areas are less likely to have broadband access and, when they do have access, are more likely to face slower average connection speeds and higher prices for basic Internet service.

Access gaps are large, speed gaps are larger

For this study, we examined data from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), broadband-speed testing firms Measurement Lab and Ookla, and broadband-pricing aggregator BroadbandNow.com. The ACS data show that the average share of households with home Internet in tribal areas is 66 percent, while the average share of households with home Internet in neighboring non-tribal areas is 87 percent. This 21-percentage-point gap in Internet access cannot be attributed solely to factors such as geographic differences, higher cost of deploying broadband in Indian Country, or lower incomes.3 Difficult-to-measure factors unique to Indian Country—e.g., complex permitting and insufficient funding opportunities available to tribes—explain a large amount of the Internet gap between tribal areas and neighboring, non-tribal areas.

While the gap in Internet access in Indian Country is large, the gaps in average download and upload speeds are even larger. See Figure 1. Download speeds from fixed broadband networks (i.e., networks that serve one particular location, such as a home or business) in tribal areas are, on average, 66 percent slower than download speeds from fixed broadband networks in neighboring non-tribal areas. Accounting for observable factors such as distance to an urban area, population density, poverty rates, and share of households with telephones only lowers the speed gap to 27 percent.4 Similarly, the average fixed-broadband upload speed in tribal areas is 78 percent slower than the average upload speed in non-tribal areas; accounting for observable factors only lowers the gap to 31 percent. The same story holds for the gap in mobile broadband speeds in tribal areas, where observed factors close the gap in average download speeds from 67 percent to 45 percent and upload speeds from 48 percent to 25 percent. Thus, as with gaps in Internet access, slower connection speeds cannot be attributed entirely to differences in geography, income, age, or basic cost factors that differ between tribal and non-tribal areas.

Access to broadband is overestimated in standard data

In our analysis, we find a striking overestimation of broadband coverage in the standard data used to assess it. This is evident in the much lower share of households that report having broadband service than the share that FCC data show to have broadband coverage. The FCC defines a census block as covered if an Internet service provider (ISP) serves at least one household in a census block. Thus, in rural areas, an entire census block, which may cover hundreds of square miles, could be considered “served” if an ISP could only potentially cover the area.

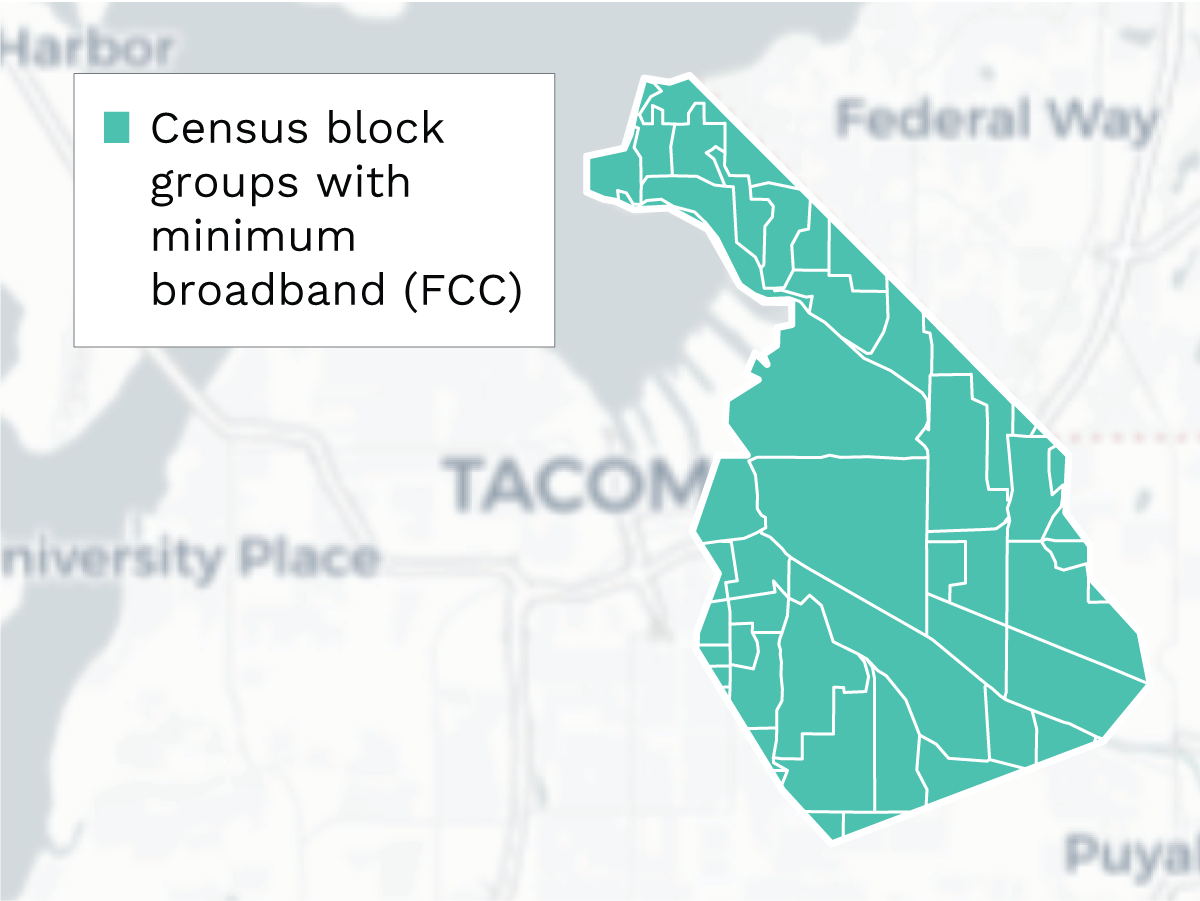

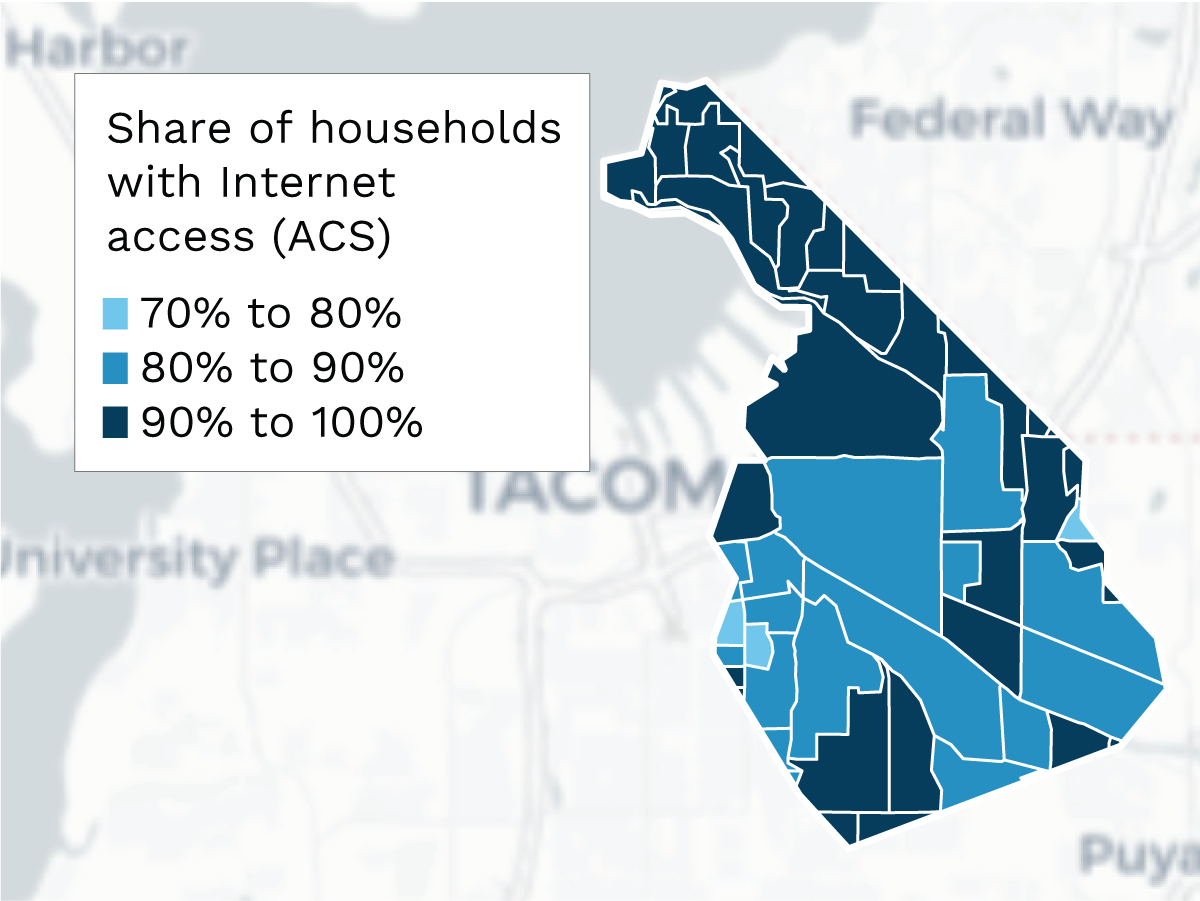

This overestimation is important for understanding broadband access in Indian Country. Figure 2 shows how dramatic the overestimation is for the Puyallup Reservation in Washington: while the FCC data reveal that the entire reservation has advertised speeds that meet the minimum standard for broadband, the ACS reveals that in pockets of this reservation, up to 30 percent of the households do not have basic Internet access at home, and even in the highest-access areas, 10 percent of households still do not have access.5

FCC Internet Coverage

Census block groups within the Puyallup Reservation with advertised speeds that meet the Federal Communications Commission’s minimum broadband requirement

ACS Internet Coverage

Share of households within the Puyallup Reservation that report having Internet access at home, according to the American Community Survey

Consistent with many reports, these results reveal a staggering gap in a wide range of important Internet outcomes. Many tribes have addressed the shortage of high-speed Internet themselves, and without these tribal efforts, the results would look even worse. Our analysis suggests that as policymakers address barriers to expanded access to broadband Internet in Indian Country, they should focus on factors specific to Indian Country that affect connection speeds, Internet quality, and, more generally, competition among broadband providers.

Endnotes

1 Darrah Blackwater, “For Tribal Lands Ravaged by COVID-19, Broadband Access Is a Matter of Life and Death.” Community Networks blog, Internet Society. May 15, 2020.

2 Robert J. Miller, “Sovereign Resilience: Reviving Private-Sector Economic Institutions in Indian Country.” BYU Law Review, Volume 2018, Issue 6. May 1, 2019.

3 In particular, we measure geographic features, such as distance to an urban area, proximity to a highway, average slope of terrain, percent of tree canopy, population density, median income and poverty rates, and share of households with telephone access.

4 We introduce a method of adopting public data from Internet speed tests, notably data from Ookla’s SpeedTest and Measurement Lab’s Network Diagnostic Tool, and from manually collected pricing data for basic broadband plans from BroadbandNow.com. Details and potential limitations of the data, as well as the methods to account for their non-representative nature, are discussed in our working paper.

5 Due to differences in how the FCC and ACS define and measure broadband access, we are unable to determine how many households located in areas where advertised Internet speeds meet the FCC’s broadband definition have chosen not to subscribe to an ISP because of cost or other factors. As such, Figure 2 is intended to provide a general sense of broadband gaps in tribal areas, not a direct, measure-to-measure comparison. For more information on the FCC and ACS definitions of Internet coverage, see the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond’s July 2019 article “Defining Broadband Coverage: It’s Complicated.” And for more on the potential for the FCC’s data to overstate broadband access, see the October 2020 article “No WAN’s Land: Mapping U.S. Broadband Coverage with Millions of Address Queries to ISPs.” (David Major, Ross Teixeira, and Jonathan Mayer, Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Internet Measurement Conference, Association for Computing Machinery, October 27, 2020.)

Matthew Gregg is a senior economist in Community Development and Engagement, where he focuses on research for the Center for Indian Country Development. He has published work on historical development in Indian Country, Indian removal, land rights, and agricultural productivity.